All man’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.

— Blaise Pascal

I.

Go to any bookstore and you’ll find shelves of books written about living in a relationship — how to find a relationship, how to hold one together once it’s found, how to survive its falling apart, how to find one again. Churches offer classes, preachers preach, teachers teach, therapists counsel about how to get and stay coupled.

Then try looking for lessons in solitude. You will search for a long while, even though more and more of us are living alone, whether by choice or circumstance. Today more than a quarter of U.S. households have only one resident. Other developed nations report higher figures, as high as 60 percent in parts of Scandinavia. This isn’t just a Western phenomenon: China and India both show rapidly expanding percentages of people living solo.

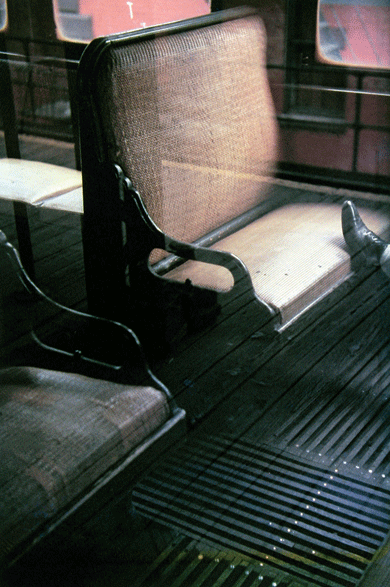

“Foot on El,” by Saul Leiter © Saul Leiter Estate. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York City.

If you return to that hypothetical bookstore, you will find that a remarkable number of the classics on its shelves were written by solitary travelers. Evidently some wisdom is available to these millions of people who are seeking, or at least experiencing, solitude.

After more than twenty years of living alone, I launched an investigation of how these authors lived out solitude in a world that seems so exclusively to celebrate coupling up, that sees bachelor- or spinsterhood as tragic. In search of a rich perspective on the solitary life, I embarked on a tour of the work, lives, and homes of writers and artists. I hoped to learn what they had to teach about the dignity and challenge of such living amid a barrage of technology that is hell-bent on ensuring that we are never, ever alone.

I am not writing about what demographers call “singles” — a word that means nothing outside the context of marriage. Nor am I writing about hermits. I am writing, rather, about “solitaries,” to use the term favored by the Trappist monk and mystic Thomas Merton. The call to solitude is universal. It requires no cloister walls and no administrative bureaucracy, only the commitment to sit down and still ourselves to our particular aloneness. I want to consider solitary people and those who seek solitude as essential threads in the human weave — “figures in the carpet,” to adapt the title of a Henry James short story narrated by just such a person — spinsters and bachelors without whom the social fabric would be threadbare, impoverished. I want to rethink our understanding of solitude and of solitaries, of those who live alone or who dedicate much of their time to being alone.

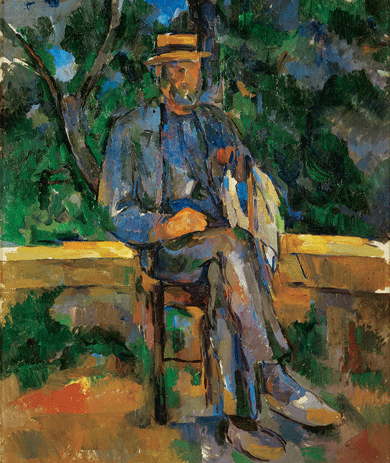

Though late in life James warned a young writer about the crushing isolation of writing, he was notably gregarious, as was Walt Whitman. Emily Dickinson, our high priestess of solitude, lived with her family and participated in its social events, which included hosting the leading literary and political figures of her time. Some of the solitaries who interest me married (e.g., Paul Cézanne, Zora Neale Hurston, Rainer Maria Rilke), though the marriages were often stormy (as in Cézanne’s case) or brief (Hurston) or carried on at a distance (Rilke). While their biographies often suggest a lifetime of living alone (e.g., Henry James, Henry David Thoreau), more emphatically and more profoundly I see their solitude enacted in their work, which is their gift to us, their spiritual children. In reading or looking at or listening to their writing or art or music, I recognized that they and I had something in common — a deep core of aloneness, a desire to define, explore, and complete the self by turning inward rather than looking outward.

In 1990, after learning of my partner’s death, a dear friend wrote, “The suffering at such times can be great, I know. But it is somehow comforting to learn, even through suffering, how large and powerful love is.” I would modify his eloquent condolence by substituting “especially” for “even” — for how else do we learn the dimensions and power of love except through suffering? Living amid the culture’s obsession with erotic passion, a solitary exists — let us not deny it — in a state of continual suffering, which is to say, in a continual opening to the possibility and grandeur of love.

To define a solitary as someone who is not married — to define solitude as the absence of coupling — is like defining silence as the absence of noise. Solitude and silence are positive gestures. This is why Buddhists say that we can learn what we need to know by sitting on a cushion. This is why I say that you can learn what you need to know from the silent, solitary discipline of writing, the discipline of art. This is why I say that solitaries possess the key to saving us from ourselves.

Among my ideal solitaries: Siddhartha Gautama sitting under the bodhi tree; Moses on the mountain, demanding a name from the voice in the wind; Jacob wrestling with his angel; Judith with the blade of her sword raised over the head of the sleeping Holofernes; John baptizing in the waters of the Jordan; Jesus fasting in the wilderness for forty days and forty nights, Jesus in his agony in the garden, Jesus in his agony on the cross; the Magdalen among the watching women, the Magdalen discovering the empty tomb; Matsuo Bash o setting out on his journey to the deep north. For exemplars closer to our time, I study the lives and work of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Paul Cézanne, Hart Crane, Dorothy Day, Emily Dickinson, Marsden Hartley, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Henry James, Thomas Merton, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty.

As I spent time studying these writers and artists, I began to experience them speaking to me, haunting me, appearing as visions, their voices urging me onward in my quest to see their solitude not as tragedy or bad luck but as an integral and necessary aspect of who they were. In their works and stories they spoke as witnesses in a great cloud around me: Thoreau (“The man who goes alone can start today; but he who travels with another must wait till that other is ready, and it may be a long time before they get off”); Louisa May Alcott (“I’d rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe”); Marianne Moore (“I should like to be alone”).

I am not interested in the possibility that solitaries might lead more carefree lives. My ideal solitary carries not less but more responsibility toward the self and the universe than those who couple. The solitary hasn’t the luxury of what Ross Douthat, a columnist for the New York Times, recently called “deep familial selfishness.” Solitude imposes on its practitioners a choice between emotional atrophy and openness to the world, with all the reward and heartbreak that generosity implies.

But now we come to the nub of the question, the hub of the turning wheel of the teachings: What figure does the solitary cut in the human tapestry? What is the usefulness of sitting alone at one’s desk and writing, especially writing those vast seas of pages that will see only the recycling bin? What is the usefulness of meditation, or of prayer? What is the usefulness of the solitary?

I grew up in a medieval landscape, in the shadow of the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani, a chunk of Norman France transplanted by the improbable forces of history to the Kentucky Knobs. As recently as the 1950s, during my childhood, the monks spoke in sign language and farmed with great draft horses, waking or leaving off their work to pray the offices when the tower bell tolled: vigils at 3:15 a.m., then lauds, terce, sext, none, vespers at sunset, and compline to close the day, the church dark except for a candlelit icon. Lord grant us a restful night and a peaceful death. O clement, o loving, o sweet Virgin Mary.

In those days, some of the choir monks — the monastic hierarchy, among them Merton, known to my family as Father Louis — escaped to Louisville and beyond to let down their tonsured hair. Meanwhile the lay brothers — the field laborers — moved discreetly but more or less freely among the villagers. Chaucer would have been puzzled by the noisy, farting internal-combustion engines (the draft horses were sold and tractors introduced in the 1950s), but otherwise he could have found among us in the village his Manciple, his Merchant, his Squire, his Man of Law, his Plowman, his Reeve, his Wife of Bath, and me, his Clerk.

At some point in the 1990s, my mother and I were driving past the great edifice of Gethsemani when she gestured at the walls, behind which she had so often ventured with a sweatshirt hood pulled over her head so that she could deliver a carload of chortling, inebriated monks back home. “Not in my lifetime but in yours,” she said, “you’ll drive past this place and say, ‘There used to be a monastery here.’ ”

Some forty monks remain at Gethsemani, down from a peak of more than 250 in Merton’s day. Their average age is pushing seventy. It was impossible for me to imagine that this institution, around which I grew up, would not be a fixture of my life — but soon enough, barring an uptick in monastic vocations, I may not have to imagine its absence.

Does ascetic practice require bricks and mortar? In our solitude, might we devise ways of supporting and disseminating ascetic virtues without monasteries? Did the disappearance of the culture that built Cluny and La Grande Chartreuse and Cîteaux mean the disappearance of the virtues they were intended to cultivate and inspire? Surely there is a vital place in our ramped-up world for simple contemplation of what is.

“The free man . . . believes in destiny and believes that it has need of him,” wrote Martin Buber, the great Jewish philosopher. “Destiny,” added Marianne Moore, the spinster poet, when she quoted Buber. “Not fate.” What is this distinction Moore takes such care to draw between destiny and fate?

Fate suggests submission to the circumstances of life; destiny suggests active engagement. The former implies some all-powerful force or figure to whose will we must submit. The latter implies that each of us is a manifestation of one of the infinite aspects of creation, whose fullest expression depends in some small but necessary way on our day-to-day, moment-to-moment decisions. We are caught — trapped, some might say — in the web of fate, but we are each just as surely among its multitude of spinners. In our spinning lies our hope; in our spinning lies our destiny. In this way, just as marriages or partnerships are not given but made, solitaries can consciously embrace and inhabit their solitude.

The solitaries who achieved destinies worthy of the name formed and cultivated special relationships with the great silence, the great Alone. I sense that relationship in their work. I read it in their poetry, in their stories, in their novels; I see it in their painting; I hear it in their music. Again and again the bachelor Giorgio Morandi painted vessels that float outside time and space in a world without surface or shadow, portraits of infinity. Erik Satie composed music in which the silences are as important as the notes. Of the solitary music teacher she created in her story “June Recital,” Eudora Welty, a spinster, later wrote:

Miss Eckhart came from me. There wasn’t any resemblance in her outward identity. . . . What counts is only what lies at the solitary core. . . . What I have put into her is my passion for my own life work, my own art. Exposing yourself to risk is a truth Miss Eckhart and I had in common. What animates me and possesses me is what drives Miss Eckhart, the love of her art and the love of giving it, the desire to give it until there is no more left.

In Welty’s story “Music from Spain,” Eugene, the protagonist, first imagines that a touring Spanish guitarist he has met has a lover in every port, only to decide that “it was more probable that the artist remained alone at night, aware of being too hard to please — and practicing on his guitar.”

I do not wish to say that being solitary is superior or inferior to being coupled, nor that the full experience of solitude requires living alone, though doing so may create a greater silence in which to hear an inner voice. Bachelorhood is a legitimate vocation. Spinsterhood is a calling, a destiny. I am seeking to understand more deeply this peculiar vocation, to which, evidently, I have been called, and which, evidently, more and more people are undertaking.

II.

A few years back, I was in a cab filled with writers when one reported that the superstar pop trio the Jonas Brothers had publicly announced their commitment to celibacy. Snickers all around. “Is that really possible?” someone asked. “I mean, do you think it’s possible for a healthy person to be celibate?” Debate on this question ensued. I, who hadn’t been unclothed in the presence of another person in longer than memory, held my tongue.

These writers, all of whom were partnered and in their thirties or forties, agreed that a victim of accident, war, or illness might have to make peace with a life without sex. Otherwise they were unanimous in questioning the legitimacy of the announcement. “It’s a public-relations ploy,” someone announced, to nods of assent. A commitment to celibacy, my colleagues decided, is either a gimmick or indicative of some deep-seated psychological trauma.

I know so many people who claim to be celibate — many within marriage — that these writers’ unwillingness to accept the practice strikes me as evidence of a failure of knowledge (how ignorant they must be of intellectual history, to be so unaware of the long list of celibate geniuses), a failure of imagination (how strange that as writers they presume their reality is of necessity everyone’s reality), or a failure of vision (how thoroughly they must have bought into the myth that life organizes itself around the literal fact of who puts what where, rather than around richer or more complex manifestations of desire).

Counter to the avalanche of messages from our culture, I recognize celibacy not as negation but as a joyous turning inward. “Inebriate of air am I, / And debauchee of dew,” wrote Emily Dickinson, most promiscuous of celibates. “Opulence in asceticism,” Marianne Moore wrote, a phrase that celebrates the solitary life even as it provides a sound bite for saving the planet.

To couple is to seek the most natural of unities: the unity with another person expressed and embodied in the act of coitus, a word that meant “meeting” or “unity” long before it came to be associated with sex. Instead of this natural unity, the solitary seeks a supernatural unity. Thoreau elaborates:

Be . . . the Lewis and Clark . . . of your own streams and oceans; explore your own higher latitudes, — with shiploads of preserved meats to support you, if they be necessary; and pile the empty cans sky-high for a sign. . . . Be a Columbus to whole new continents and worlds within you, opening new channels, not of trade, but of thought. . . . It is easier to sail many thousand miles through cold and storm and cannibals . . . than it is to explore the private sea, the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean of one’s being alone. . . . Let them wander. . . . I have more of God, they more of the road.

“I have more of God”: Yes, exactly so. That is the supernatural unity; that is the interior journey’s goalless goal, the solitary’s reward.

Let us acknowledge that solitude and celibacy are related to but not necessary conditions for each other. I have known garrulous celibates; I have known promiscuous solitaries. But a conscious decision to refrain from sex can be a powerful incarnation of solitude. Actively chosen celibacy and solitude represent decisions to commit oneself for whatever length of time to a discipline — a forgoing of one delight (the charms of dalliance, the pleasures of light company) for a different, longer-term undertaking: the deepening of the self, the interior journey.

My monk friends, men and women, brothers and sisters, speak with passion and eloquence of celibacy as a conscious decision to fulfill oneself through a communion with all, rather than with a particular individual. “Instead of limiting myself to one person,” they say, “I decided to open myself to everyone and, through everyone, to God.”

“Untitled (February 13, 2012, 12:20 p.m.),” by Richard Misrach, whose work is on view this month at Fraenkel Gallery, in San Francisco, and whose monograph The Mysterious Opacity of Other Beings will be published next month by Aperture © The artist. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York City; and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles.

To my ears, a generous and lovely assertion. But I add that in the 1970s, gay friends who hung out in San Francisco’s bathhouses described their promiscuous nights in nearly identical terms: “I choose to give myself to everybody instead of to just one person.” More than one added, “And that’s my religion.”

The echo is not coincidental. Celibacy and libertinism are antipodes, opposing poles that define desire. They are more similar than different, and both are practiced by people of great longing.

In the 1930s, my mother danced on tabletops and wore skirtless bathing suits and was seduced from teetotaling Protestantism into the Roman Catholic Church by the smells and bells, incense and music, that she encountered in her one semester in college, when she roomed across the street from a Roman Catholic church. Marrying my father provided an excuse for a conversion to which she had long been drawn, the most rebellious, exotic, passionate act that a woman from the Bible Belt could accomplish.

I will be grateful for a lifetime to the Roman Catholic Church for instilling in me a sense of mystery and of manners (to invoke Flannery O’Connor’s phrase) and to my mother for laying down a baseline of Protestant skepticism for that potent mix. Ninety-eight years old, she grows ever weaker as I write these words, and in her honor I inject some leavening into my treatment of what should be a cheerful topic by citing Zora Neale Hurston, who wrote in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road:

Under the spell of moonlight, music, flowers, or the cut and smell of good tweeds, I sometimes feel the divine urge for an hour, a day, or maybe a week. Then it is gone and my interest returns to corn pone and mustard greens, or rubbing a paragraph with a soft cloth. Then my ex-sharer of a mood calls up in a fevered voice and reminds me of every silly thing I said, and eggs me on to say them all over again. It is the third presentation of turkey hash after Christmas. . . . I was sincere for the moment in which I said the things. It is strictly a matter of time. It was true for the moment, but the next day or the next week, is not that moment. . . . So the great difficulty lies in trying to transpose last night’s moment to a day which has no knowledge of it. That look, that tender touch, was issued by the mint of the richest of all kingdoms. That same expression of today is utter counterfeit, or at best the wildest of inflation. What could be more zestless than passing out cancelled checks? It is wrong to be called faithless under circumstances like that. What to do?

Hurston married three times, with each marriage effectively over within months, though the divorces sometimes took years to be finalized. Consider, please, the disservice to civilization of imposing on this free spirit, this great writer and servant to humanity, this great solitary, vows of either celibacy or marriage.

“Every limit is a beginning as well as an ending,” George Eliot writes in the last chapter of Middlemarch. Many seek those limits in marriage. Some seek them in vowed celibacy. Hurston found them in her writing, her lifelong project of preserving in words the religions of Africa as they appeared after being transplanted to the New World.

I have met free spirits who so clearly express their untrammeled selves that their partners know from the first what they’re getting into. I am not such a person, nor, do I think, are most of us. Most of us need limits and thrive within them. But I know that I, a gay man, am lucky that I was chosen for the demimonde, which taught me that love — true love, real love, God’s love — exists outside and apart from the laws of (mostly) men.

That my long bachelorhood may end tomorrow I do not doubt. Asked once by a middle-aged woman when she would find love, my Zen teacher scratched his head and responded, “Maybe next Wednesday?” The most stable of marriages have been known to founder. Monks and priests have left their religious orders on a moment’s notice; lifelong bachelors and spinsters couple and marry late in their lives.

But I have lived a long time alone. I seek to live not in anticipation but in embrace of the life I have been given. A great deal of virtue is born of necessity. I may not have chosen to be single in midlife, and I may not have chosen to be celibate, but here is me, I am it. I can choose whether simply to endure my condition with my attention focused elsewhere and outward, wondering whether I will meet Mr. or Ms. Perfect at today’s aerobics class. I can see my life without sex as a way station, a year or a decade long, between sexual encounters. Or I can inhabit it, against all the messages of contemporary culture, as a legitimate way of being, an opportunity to focus all that longing on my heart’s desire, whether that be a community garden or world peace.

If we define celibacy simply as not having sex, then most of us are celibate most of the time. Evidently, to be worthy of the name something greater must be at stake. Celibacy must involve a vow — a promise — to oneself or to others or to God. Or we might draw a distinction between celibacy, which is the state of not having sex (I’m being celibate as I type these words), and restraint, which is a conscious decision to refrain from sexual activity in a particular situation in service to a larger principle or goal. Like a marriage vow, restraint constitutes a voluntary assumption of suffering — a sacrifice in order to serve a larger purpose.

The English Catholic G. K. Chesterton wrote:

Virtue is not the absence of vices or the avoidance of moral dangers; virtue is a vivid and separate thing, like pain or a particular smell. . . . Chastity does not mean abstention from sexual wrong; it means something flaming, like Joan of Arc.

I would define chastity as moderation in all matters — including self-mortification and alcohol. All the same, “something flaming” — desire not as a conflagration but as a steadily burning, light-giving lamp — strikes me as a fine description of what the celibate aspires to. Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross — or, for that matter, Jesus and the Buddha — did not set themselves above desire. They took charge of desire and so successfully focused it inward that they could then turn its energy outward. They sought not to raise themselves above the created world — the errand of a fool or a tyrant — but to more thoroughly integrate themselves with it.

Rather than Chesterton’s “chastity,” I favor the Buddhist phrase “right conduct.” A vow to practice right conduct strikes me as more flexible, more encompassing, and more challenging than a vow of celibacy. Such a vow places responsibility and struggle where they belong — with the individual conscience. The word “restraint” implies the asking of an essential question, one that is more important now than ever, and is antithetical both to capitalism and to science as we practice them: Because we can do something, must we do it?

But then what is the purpose of a vow? Why make a promise regarding any practice, whether it be trivial or life-changing, to oneself or to another human being or to God? And if that promise can be easily undone (as with today’s marriage vows), what is the point?

A vow exists to offer, in the words of William James, a “moral equivalent of war” — a discipline that enables the virtues of sacrifice. “A permanently successful peace-economy cannot be a simple pleasure economy,” James wrote, and yet the choice of military service, marriage, or pursuit of the “pleasure economy” is almost all our society offers young people searching for a sense of purpose in their lives.

As a professor at a large public university, I can report an increasing urgency and hunger among my undergraduate students for an outlet for their desire that will bring meaning to their lives. Admittedly, they’re a self-selected group — they’ve chosen to take advanced writing courses — but that does not change the reality that our vast government and corporate apparatus offers the conscience-driven student limited options compared with those offered to students who seek more explicitly self-interested careers.

I accept and respect the necessity of the great edifices of the law — the church, the government. But a vow is an intensely personal gesture — a means of placing limits on desire, of creating an engine for its fuel. I salute the courage of those who make such declarations in public, but I admire more deeply those who honor their vows in the solitude of their hearts. A vow may be taken for a lifetime, but it’s lived out day to day, hour by hour, one encounter at a time, by little and by little. Like virtue, it defines itself in the doing.

Let me be frank: how I miss the touch of a familiar and shaping hand; how I miss not the sex but what precedes and follows it, the intimacy and the alienation, the strangeness to another and to oneself, the being naked to another, the being naked to oneself. Post coitum omne animal triste est: after sex every animal is sad. I miss the sadness. And yes, I miss even the arguments, because underlying the bickering was always this taken-for-granted certainty: How much I must matter to this person that I rouse him to such anger! Isn’t any relationship, even one that is troubled and unhappy, worth the price of that ticket? What comparable joys and sorrows can solitude offer?

I hear the answer in this quiet room; I see it in the angle of the autumn sun. The great, incomparable reward of being alone is the opportunity, if I can be large enough to rise to its occasion, to encounter the great silence at the core of being, a silence that is both uniquely mine and one with the background hum of the universe. To live for the changing of the light seems adequate reward.

Listen to Marianne Moore writing about Henry James: “Things for Henry James glow, flush, glimmer, vibrate, shine, hum, bristle, reverberate. Joy, bliss, ecstasies, intoxication, a sense of trembling in every limb. . . . Idealism . . . willing to make sacrifices for its self-preservation was always an element in [his] conjuring wand.” Note Moore’s invocation of “sacrifice,” which Merton named as the most essential quality of true love.

I am not offering a rose-strewn path. The solitary’s journey is fraught. Again and again our solitaries present us with this bedrock philosophy of previous ages, this truth so unpopular in our consumerist age: The path to liberation runs through suffering. The journey to peace runs not around but through suffering. Whitman in the hospitals, Dickinson in her room: The self is the vehicle, the boat that takes us from loneliness to aloneness — that takes us on the journey to solitude.

III.

Intelligent design, or, if you prefer, a concatenation of circumstance and frequent-flier miles, brought me to my mother, under the care of the Sisters of Loretto. On a good day — these are fewer and farther apart — she tells stories of driving Merton — Father Louis — to the train station in the family’s battered red Ford Country Squire. From there he took the train to Louisville, where, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, he had a profound vision of the interconnectedness of every creature with the planet and with God.

Her story provokes another: of the return of Merton’s body aboard a military-transport plane from Thailand, Merton the pacifist mystic monk in his shiny black body bag amid a hundred and more dead soldiers in their shiny black body bags — an image of solitude amid unity if ever one was known. As my mother tells it, the coroner called in my father, together with several monks, to identify the body, but after more than a week in a tropical country it was too decomposed to identify except by its false teeth, which Merton’s Lexington dentist recognized, and which are still, or so my mother believes, in his possession.

That story leads to her story of Merton’s funeral, where, as the body was lowered into the earth — the advanced decomposition necessitated a coffin, a departure from the usual Trappist practice of burial in nothing more than robes — a woman in a long black veil ran from the knoll of plain white crosses across a meadow dusted white with December snow and hail. “Joan Baez,” my mother says confidently, and I want to believe her. It was 1968, a year that gave birth to such stories.

Now, standing amid those crosses where the abbey’s great bell tolls the hours, I realize that the monastery cemetery holds the greatest concentration of the dead of my life, greater even than the Golden Gate, repository for the ashes of so many friends who died of AIDS. Here at Gethsemani I find crosses for Alfred, Alban, Guerric, Giles, Stephen, Claude, Wilfrid, Thomas, Father Matthew, Father Louis, and — buried not here but in my heart — those monks who returned to the secular world: Lavrans, Donald, Joshua, and Clement, who gave his birth name, Fintan, as my first name and devised the fruitcake recipe that made the abbey prosperous.

Recently I attended a conference where a Native American–rights activist asked her audience to imagine the absurd. Thirty years ago, she said, imagining restaurants without smoke would have been absurd. An African-American president. State recognition of same-gender marriage. So I took up her challenge and imagined a world in which the people of compassion have reclaimed the institutions and the language of compassion — words like holy, sacred, sacrifice, divine, grace, reverence, love, God — words that have been handed over to demagogues.

Could solitaries model the choice for reverence over irony? Instead of conquering nations or mountains or outer space, might we set out to conquer our need to conquer? If that seems a tall order, I offer you Paul Cézanne, painting himself to the point of diabetic collapse, reinventing painting. Think about the hallucinatory quality of his late work; think about how modern art owes itself to solitude and low blood sugar. I offer Eudora Welty, writing magical realism when Gabriel García Márquez was a teenager. Henry James, portraying the caustic corruptions of fortress marriage, living alone in Lamb House by the sea. Zora Neale Hurston, who nurtured a flame of mysticism in a world hostile to it, and who showed that through her wits alone a black woman could live by her own rules, and who died in poverty and was buried in an unmarked grave in a potter’s field. Thomas Merton, who spent twenty years in a monastery preparing for his true vocation, which was solitude. Walt Whitman, who taught us how to be American. Emily Dickinson, his sister in solitude, who taught us how to be alive to the world, most especially to the suffering of its solitaries. I offer you Jesus, that renegade proto-feminist communitarian bachelor Jew, who reminded us of the lesson first set forth a thousand years earlier in the Hebrews’ holy book: to love our neighbors as ourselves. I offer you Siddhartha Gautama, who sat in solitude to achieve the understanding that everyone and everything are one.

After more than a decade of assembling evidence of his monastic order’s history of supporting hermits, Merton received permission to retreat from the communal life of the monastery to a hermitage on Gethsemani’s grounds. His porch offered a view across meadows rolling toward Muldraugh’s Hill, the blue horizon of my childhood, which extends in a hundred-plus-mile arc around the Kentucky Bluegrass.

Merton’s hermitage still overlooks those meadows. But the monks now report their silent retreatants’ delight at the installation of the tallest cell tower I’ve seen, the red light at its top a continual winking feature of the view from Merton’s porch.

Photograph of the grounds at Gethsemani, by Thomas Merton © Merton Legacy Trust/Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

The multiplication of our society’s demons has been accompanied by a ratcheting up of the sources and volume of its background noise. What is the point of the chatter and diversions of our lives, except to keep the demons at bay? Meanwhile, we are creating demons faster than we can create noise to drown them out — environmental devastation, global warming, the growing gap between the rich and the poor, uncontrolled population growth, uncontrolled consumption held up by the media as the glittering purpose of life.

The appropriate response is not more noise. The appropriate response is more silence.

To choose to be alone is to bait the trap, to create a space the demons cannot resist entering. And that’s the good news: The demons that enter can be named, written about, and tamed through the miracle of the healing word, the miracle of art, the miracle of silence.

“I find ecstasy in living — the mere sense of living is joy enough,” Dickinson wrote. That joy, that ecstasy that she describes — I know it is not limited to celibates or solitaries, but I also know it shows itself to us in particular ways that are denied those who are coupled. Visions appear to the solitary prophet. Revelations arrive in silence and solitude. Emily Dickinson at her sunny, south-facing window, surveying the church she declined to attend, Buddha under the bodhi tree, Moses on the mountain, Jesus in the desert, Julian of Norwich in her cell, Jane Austen taking notes on the edges of the society she so vividly portrayed, Vincent van Gogh at his canvas, Zora Neale Hurston experiencing extraordinary visions while walking home alone — for these people, solitude was a vehicle for the imagination.

Only in solitude could these solitaries fulfill their destinies — become not partial but whole — teachers for you and me, teachers for and of the universe. Like Jesus, bachelor for the ages, they keep ever before us the ideal toward which we may strive. They raise the bar of what it means to be alive. By striving toward their ideal we become better than we thought ourselves capable of being.

Let us imagine, as both William James and Thomas Merton proposed, a secular monasticism — a conversatio morum, a great conversion of manners, in the terminology of the monastic vows — an integration of mystery into our daily lives, an opulent asceticism. Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson will be our entirely worthy Peter and Paul, and we will have as the crowning achievement of the American experiment an authentically American destiny. In this conception of the world, we celebrate friendship as the queen of virtues, and recognize it as the foundation for all worthy human connection, including marriage.

If this sounds utopian, I offer Zoketsu Norman Fischer’s Everyday Zen, whose goal is to integrate Zen meditation and principles — which is to say, monastic principles — into daily life. I offer the oblate movement — even as the numbers decline in Christian religious orders, the number of people who have taken vows of allegiance to their principles is growing. I offer the growing integration of the concept of sustainability into our everyday choices. I offer the growing understanding within science and medicine of the interrelatedness of all disciplines, of all life, including that other version of life we call death.

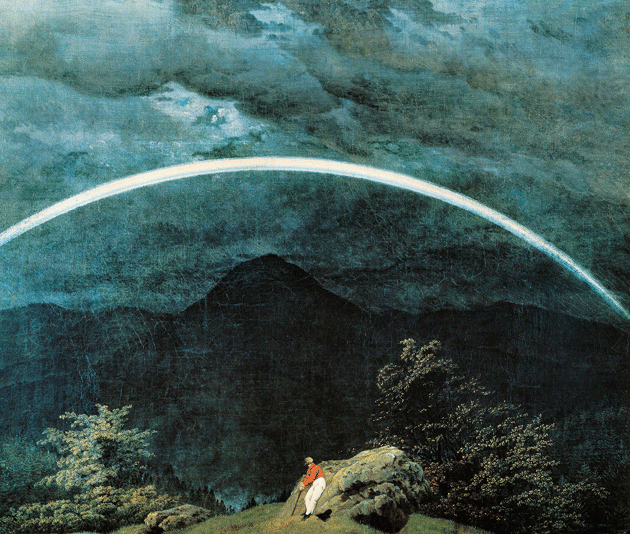

Mountain Landscape with Rainbow (detail), by Caspar David Friedrich © De Agostini Picture Library/Bridgeman Images

I point to the great failure of the left — as played out in the presidency of Barack Obama, who was inaugurated with such hope — to provide a vision sufficiently grand to counter the call to unrestrained consumption that is trotted before us at every hour of every day in every popular medium. My vision is no more fantastic than colonies on Mars, solar grids in space, heat transfer from the oceans, impregnable vaults for nuclear waste, carbon-dioxide storage under the Great Plains, or any of hundreds of proposals our politicians and research institutions and media take seriously. It requires no trillion-dollar investment in technology, which history teaches us will inevitably generate problems equal to or greater than those they solve.

Merton writes of solitaries that we are “a mute witness, a secret and even invisible expression of love which takes the form of [our] own option for solitude in preference to the acceptance of social fictions.” And what love are we solitaries mute witnesses to? The omnipresence of great aloneness, the infinite possibilities of no duality, no separation between you and me, between the speaker and the spoken to, the dancer and his dance, the writer and her reader, the people and our earth.