Per Se (“Through Itself”) lives on the fourth floor of the Time Warner Center, a shopping mall at Columbus Circle, close to Central Park. It is by reputation — which is to say gushing reviews and accolades and gasps — the best restaurant in New York City. And so I, a British restaurant critic, commissioned to review the most extravagant dishes of the age, borne across the ocean on waves of hagiography, arrive at Through Itself expecting the Ten Commandments in cheese straws.

There are three doors to Through Itself; two are real, one is fake. The fake door is tall and blue and pleasing, with a golden knocker. It is a door from a fairy tale. The real doors are tinted glass, and glide by themselves, because no customer at Through Itself can be expected to do anything as pedestrian as open a door. I’m not aware of this, so I tug at the fake door, giggling, until rescued by an employee, whom I remember only as a pair of bewildered shoulders. I am made “comfortable in the salon,” as if ill or a baby, with a nonalcoholic mojito. It is a generic luxury “salon,” for they are self-replicating: a puddle of browns and golds, lit by a fire with no warmth. There is a copy of something called Finesse magazine, which is an homage to Through Itself, and whose editorial mission, if it has one, is “canapé advertorial.”

Through Itself is not a restaurant, although it looks like one. It may even think it is one. It is a cult. It was created in 2004 by Thomas Keller of The French Laundry, in Yountville, California. He is always called Chef Keller, and for some reason when I think of him I imagine him traveling the world and meeting international tennis players. But I do not need to meet him; I am eating inside his head.

Phoebe Damrosch, a former waiter at Through Itself, wrote a book called Service Included, a marvelously prosaic title with a misleading subtitle: Four-Star Secrets of an Eavesdropping Waiter. Damrosch does not eavesdrop on her customers — she is too bewitched for that — but on herself. “There were philosophies,” she writes, “laws, uniforms, elaborate rituals, an unspoken code of honor and integrity, and, most important, a powerful leader.”

If the restaurant is a cult, what then is the diner? A goose in a dress of course, a hostage to be force-fed a nine-course tasting menu by Chef Keller and his acolytes. Here the chef is in control. The client, meanwhile, is a masochist waiting to be beaten with a breadstick, spoiled with minute and sumptuous portions that satisfy, and yet incite, one’s greed. The restaurant seethes with psychological undercurrents and tiny pricks of warfare. It is not relaxing.

The dining room: sixteen tables on two levels, with views of Columbus Circle and Central Park. The walls are beige, with hangings that look like oars that could not row a boat; the carpet is brown, with cream squiggles. It is gloomy and quiet, the only sound a murmur. My companion thinks it looks like an Ibis hotel, with a chair for your handbag, or an airport lounge in Dubai.

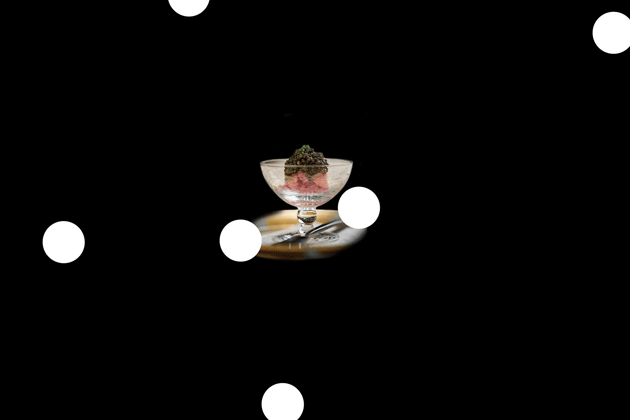

The menu is oddly punctuated and capitalized: “Oysters and Pearls”; “Tsar Imperial Ossetra Caviar”; “Salad of Delta Green Asparagus”; “Hudson Valley Moulard Duck Foie Gras ‘Pastrami’ ”; “Charcoal Grilled Pacific Hamachi”; “Maine Sea Scallop ‘Poêlée’ ”; “Champignons de Paris Farcis au Cervelas Truffé”; “Elysian Fields Farm’s ‘Selle d’Agneau’ ”; “Jasper Hill Farm’s ‘Harbison’ ”; “Assortment of Desserts.”

How does the food taste? To ask that is to miss the point of Through Itself. This food is not designed to be eaten, an incidental process. It is designed to make your business rival claw his eyes out. It could be a yacht, a house, or a valuable, rare, and miniature dog. But I can tell you that the cornet of salmon — world famous in canapé circles — is crisp and light and I enjoyed it; that there are six kinds of table salt and two exquisite lumps of butter, one shaped like a miniature beehive and another shaped like a quenelle; that a salad of fruits and nuts has such a discordant splice of flavors it is almost revolting; that the lamb is good; and that, generally, the food is so overtended and overdressed I am amazed it has not developed the ability to scream in your face, walk off by itself, and sulk in its room.

It rolls out with precise, relentless expertise. The waiters are dehumanized, reduced to multiple efficient arms. “The Cappuccino of Forest Mushrooms,” Damrosch writes,

called for one person to hold the soup terrine on a tray, one to hold mushroom biscotti, the mushroom foam, and the mushroom dusting powder (à la cinnamon) on a tray, and one to serve the soup. If a maître d’ stepped in to help, he made four. If the sommelier happened to be around pouring wine, he became a fifth. The backserver pouring water and serving bread made six.

I don’t think they like the customers. Perhaps they are annoyed that Through Itself charges a 20 percent “service fee” for private dining — Service Not Included? — and does not pass it on to them. (As this essay went to press, New York State concluded that Through Itself had violated state labor law and would pay $500,000 in reparations to the affected employees.) Or perhaps the clients are too greedy? In Service Included, Damrosch rages against a customer who seeks extra canapés: “Extra canapés are a gift from the chef and to ask for them, even if you are willing to pay, would be like calling a dinner guest and telling them that instead of a bottle of wine or some flowers, you would like them to weave you a new tablecloth.” Surely this would be comparable only if your theoretical dinner guest owned a tablecloth factory? The waiter, a man with huge arms, presumably from carrying a city of plates, asks: “How is your drink?” “Watery,” I say, since he asked. Another is brought and he is here again, prodding: “How is your fauxjito?” It’s hard to be afraid of someone who says “fauxjito” with such emphasis, but I think I have hurt his feelings; things are not the same after that. During the cheese course, when I do not understand whether the cheese is an alcoholic or a recovering cheese, he asks me, very slowly: “Do you understand what I am saying?” Each word is followed by a full stop. I have never found servility quite so threatening.

The provenance of the cheese is part of the cult. Through Itself has commissioned a book about its suppliers, who are, gaily, trapped inside some of the maddest copywriting I have ever read. For instance: “In the rolling hills of Sonoma, perched atop a fog-covered ridge, a conductor orchestrates the transformation of humble milk into some of the finest cheeses in America.” This, on Animal Farm in Orwell, Vermont, is self-pitying, as well as being a very self-conscious and buttery critique of Communism: “To make butter, one must be willing to sacrifice a measure of free will and live according to the needs of animals.” If all farmers were this credulous, the world would starve.

Animal Farm has a cow named Keller — as in Major, Snowball, Napoleon, and Keller — and, now that I think of it, why shouldn’t a butter farm criticize Communism, give George Orwell a kick, and then, one day, execute its cow/chef? I am certain that Wendy’s has something to say about Alexis de Tocqueville, and maybe McDonald’s does, too, but about Jean-Jacques Rousseau? Some passages are merely odd; for instance, this, from Devil’s Gulch Ranch, in Nicasio, California: “Rabbits are important.” Do they rustle rabbits at Devil’s Gulch, or just keep them in pens? This is the countryside idealized, trivialized, and made ridiculous; this is Marie Antoinette’s Petit Trianon in a mall.

Animal Farm may be a metaphor for the anxieties of those who dine at Through Itself: they are hungry, but only for status; loveless, for what love could there be when a waiter must stand with his feet exactly six inches apart, as related in Service Included? Through Itself is such a preposterous restaurant, I wonder if a whole civilization has gone mad and it has been sent as an omen to tell us of the end of the world — not in word, as is usual, but in salad.

Nor am I sure that the human body is meant to digest, at one sitting, many kinds of over-laundered fish and meat. Perhaps this is a dining experience designed for a yet-to-be-evolved species of human? Because later, in my hotel room, a frightening expanse of gray carpet in Midtown near the Empire State Building, I put aside the souvenirs of Through Itself — menu, pastries, chocolates — and vomit half of $798.06. That is my review: a writer may scribble her fantasies but a stomach never lies. It could have been jet lag, I suppose, but I think it was disgust. Those poor little nuts. They deserved better.

Eleven Madison Park is on the ground floor of the Metropolitan Life North Building. This skyscraper was designed to be a hundred stories high; then the 1929 Wall Street crash, like the finger of God, accurate and pitiless, decapitated it at the thirty-second floor. This is a grand restaurant built by insurers, seemingly intended to entertain something inhumanly large — a ship, for instance. If a ship could walk and eat and hold a conversation, it would come here. Freud’s ghost is everywhere in this bright void where light flies through the windows in great shafts, bouncing against gold and brown, and diners float like tiny stick men. It is less horrifying than Through Itself, though some of the diners — birthday parties and lovers? — are giggling at their courage in attempting a tasting menu and all the whimsy it requires.

This restaurant “focuses on the extraordinary agricultural bounty of New York and on the centuries-old culinary traditions that have taken root here.” The chef is Daniel Humm. His food is brought on a fantastical array of china plates and silverware in fabulous permutations. Pretzels on silver hooks? Ornamental charcoal? Dry ice? Internal organs? Domes?

It is ragingly tasteless. One tiny dish of salmon, black rye, and pickled cucumber is, we are told, “inspired by immigrants.” Were they very tiny immigrants? Our main waiter — an efficient woman with a calmly quizzical face, who manages the spiel without once acknowledging its absurdity — repeats it with no intonation but with a twist: “based on the immigrant experience.” Only a person with limited access to immigrants would design a paean to their native cuisine — in this case, Ashkenazi Jewish — within a $640.02 meal (service included) and expect anything other than appalled laughter, or a burp of shame. This is the anti-intellectualism — and pretension — of this particular age of excess.

The secondary waiter is simply a human trolley with a rectangular face and obedient eyebrows; he holds the things for the first waiter to place on the table and rushes away on his feet/wheels.

The Hudson Valley Foie Gras (“Seared with Brussels Sprouts and Smoked Eel”) is divine; the Widow’s Hole Oysters (“Hot and Cold with Apple and Black Chestnuts”) are excellent if weirdly capitalized; but the remarkable thing is the turnip course. A turnip, as you know, should be allowed to be a turnip; that is for the best. A turnip is a humble root vegetable, and should not be expected to close a Broadway musical, solve a financial crisis, or achieve self-consciousness through the application of technology. But here Turnip — with Variations in its Own Broth (in honor of Johann Sebastian Bach?) — is presented without even a carrot for company. The chef — was it actually Humm? — wanted to save the turnip from itself and remake it as something wonderful, because then — then! — he could have proved something to himself. What that is, we will never know; some people can speak only in vegetable. The chef should not have bothered. It is entirely revolting, and the most grievous result of the cult of chef I have yet witnessed. Could no one have told him, “Don’t bother with the turnip course, you’re wasting your time, it’s a turnip”? Bah! Surrounded by acolytes — by enablers — the chef dreams his turnipy dreams and does things to turnips that should not be done to any root vegetable.

Presently, as if we were not amazed enough by the transubstantiation of the turnip, they bring a golden, inflated pig’s bladder in a dish, as a cat might bring in a dead bird — look, a bladder, see how much urine a pig can store in itself! It is an inedible friend to the celery root; it exists to make celery root seem more interesting than it really is. In this, it succeeds. My companion looks as if she wants to hide under the table until the bladder is removed by human trolley. The Finger Lakes Duck (“Dry-Aged with Pear, Mushroom, and Duck Jus”) is better, even if it has lavender flying out of its bum like a fragrant mauve comet and is now a duck/garden on a plate because a duck by itself — well, that is not good enough. These men didn’t make a billion dollars to eat duck the way other people do.

It is not, to me, food, because it owes more to obsession than to love. It is not, psychologically, nourishing. It is weaponized food, food tortured and contorted beyond what is reasonable; food taken to its illogical conclusion; food not to feed yourself but to thwart other people.

We are, for some reason, invited into the kitchen. It is immensely clean, large, and busy, and motivational words line a wall: cool; endless reinvention; inspired; forward moving; fresh; collaborative; spontaneous; vibrant; adventurous; light; innovative. Similar words were written on the walls of the McDonald’s in Olympic Park in London in 2012, but I do not mention this. We stand at a tiny station and watch a woman prepare egg creams. This soothes me — ah, sugar! — and then we return to our table for dessert, which is Maple Bourbon Barrel Aged with Milk and Shaved Ice. It is sugared snow in Manhattan in springtime; it is snow that you eat when you have lost your innocence; it is — what else? — Charles Foster Kane’s snow!

Across the river, in Brooklyn, is Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare: “Brooklyn’s only three Michelin-starred restaurant.” It is attached to a supermarket, also called Brooklyn Fare, which has homilies painted on its windows: feeling bittersweet? no need to push! The buzz surrounding this restaurant comes at least in part from the neighborhood at the edge of Downtown Brooklyn. Here, the novelty is the relative poverty of other people and their odd ways: emerge from Chef’s Table and fall over a homeless person. This is Brooklyn as theme park.

Chef’s Table is, as food journalists — or marketing people posing as food journalists, or food journalists in thrall to marketing people, of whom there are too many — will tell you, hell to get into. I never really believe it when restaurants say this; there is always a table. But it is the first move in the game: create a yearning for that which others cannot have and you can sell it at any price.

Each Monday morning, at ten-thirty, you — or a person representing you — are invited to telephone for a table six weeks later. “All reservations,” says the website, which is the most explicitly controlling — okay, rude — I have yet encountered, “for the sixth week out are booked at that time.” You then receive an email that may have been written by a lawyer. It says the kinds of things lawyers say, in the language that lawyers use. It is comprehensive and sadistic, and it does not tell you to have a nice day, not ever. For instance: “We welcome you to enjoy your food free of distractions. We request no pictures or notes be taken.” Payment must be made in advance. No sneakers. No vegetarians. No flip-flops. No joy. (I invented the last one.) Because none of this is for us. It is for them. It would have been kinder to say, “We are narcissistic paranoiacs who love tiny little fish and will share them with you for money. We request no pictures or notes be taken.”

Each Monday morning, at ten-thirty, you — or a person representing you — are invited to telephone for a table six weeks later. “All reservations,” says the website, which is the most explicitly controlling — okay, rude — I have yet encountered, “for the sixth week out are booked at that time.” You then receive an email that may have been written by a lawyer. It says the kinds of things lawyers say, in the language that lawyers use. It is comprehensive and sadistic, and it does not tell you to have a nice day, not ever. For instance: “We welcome you to enjoy your food free of distractions. We request no pictures or notes be taken.” Payment must be made in advance. No sneakers. No vegetarians. No flip-flops. No joy. (I invented the last one.) Because none of this is for us. It is for them. It would have been kinder to say, “We are narcissistic paranoiacs who love tiny little fish and will share them with you for money. We request no pictures or notes be taken.”

We are offered a table for ten o’clock on Thursday night. We take it, but the day before the meal, we are told to come at six. The customer is servile to the product. Thus is the power of marketing!

We are seated in an industrial-style, anti-décor room; that is, a kitchen. Kitchens are interesting to people who rarely go in them, riveting even. You enter the restaurant through a series of incomprehensible plastic flaps. Maybe they are homeless-person repellents? You sit down in the kitchen. It has a bright buffed bar and eighteen stools with backs. The emails and marketing literature are effective. The room seethes with angry anticipation; this better be good, after the emails and the trip to Downtown Brooklyn!

There are five chefs and three waiters: one to serve the food, one to arrange the cutlery, one to serve the drinks. We all eat the same food at the same time, but there is no camaraderie between the diners; in fact, we avoid one another, which is preposterous in a room this size. For, at these prices, who would risk marring their experience with an uncontrolled — and uncontrollable — interaction with a stranger who was not in the business of serving you? I quickly realize that to attempt a noncurated social encounter here would be equivalent to asking a fellow diner for some deviant form of sexual intercourse, or a bite of his squid.

I ask the waiter why I can’t take notes or pictures. Can I can sketch something? Doodle? Write a play? You cannot separate me from my notebook; if I cannot bear witness to raw fish, what am I? He, a tidy young man in the inevitable suit, says they are afraid of “leaks.” These people are mad; why can’t I have an international scoop relating to fish and how it looks and what it does and what sauce is doused upon its lifeless flesh? He looks solemn — there are no grins here — but his mouth curls up. He gave me that.

The word “leak” offends us investigative journalists. You cannot leak the details of a piece of fish, you can only report them. But not here. Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare has insulted whistle-blowers everywhere; see how the luxury-goods industry steals the language of victimhood and dismembers it for its own ends, rendering it worthless! We decide we hate Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare and we behave badly; in this restaurant, anything other than gormless supplication to the fish is behaving badly. Please tell me just a little more about the salmon? Did it swim on the left- or the right-hand side of the river? Was it educated? Did it have any dreams left? We snigger. We complain that other customers are texting and taking photographs of the fish — they are “leaking” — but not us, you can depend on us. We would never threaten the national security of this kitchen and let the Islamic State in to attack your wasabi. We run through the homeless-person-repellent flaps and smoke cigarettes when we should have waited, like girls for Communion with open mouths and pinkish tongues, for the next beatified lump.

Between these transgressions, we eat a series of tiny pieces of food, each delivered with its companion essay spoken in an extraordinary monotone, none of which I can relate to you because I am not allowed to take notes. (I am too ashamed to hide in the bathroom to take notes between courses, as Service Included tells us the New York Times critic did.) It is fish. It is very good fish delivered with a self-importance that feels very close to aggression, and it is not worth the journey.

As I leave I am partially flayed. A tiny girl has pushed her stool a few feet out from the bar, for reasons I do not understand. Her tiny legs sway in the void. Perhaps she is admiring them, or trying to eat them? (Still stuck to her, they are fresh enough.) In any case, she does not know how to sit on a stool, which is a basic skill. I try to squeeze past — I am English, after all — and cut myself on a piece of metal sticking out of the wall; maybe it’s a thermostat, or a fire alarm. I don’t know. I scream; after an evening in this kitchen, it comes naturally. Seventeen faces — fourteen customers and three waiters — turn to me neutrally, perplexed. What is this noise that has disturbed our three-star Michelin kitchen experience (and in Brooklyn too)? Is it a large piece of fish? (Is everybody food now, or if not food then potential food?) I ask the female waiter what maimed me. “I have to go!” she shouts. She cannot associate with the screamer. The male waiter opens the door with a big, fake, horrifying smile. “Goodbye!” he sings. We exit the flaps. We were not grateful enough, you see; we did not prostrate ourselves before the brand.

Chef’s Table wreaked revenge for my ingratitude. Restaurants are systems; systems have weapons. Outside I scribble down what I can remember of the menu. I lie, of course, I write it on my iPhone, because print is dead. And it scrubbed itself as the paper and pencil I was denied would never do, although I could conceivably have left them in a taxi. So I can only say I ate a procession of tiny and exquisite pieces of fish and seafood, including, I think, golden-eye snapper, scallop, lobster, and mackerel; plus something called, mysteriously, “the root” (these may be my words, I am not sure); and a wondrous, sweet green cake that shed green dust on the counter, like a fleeting dream; and that I was flayed, too, and there was blood on my piled-up clothes on the floor of the frightening hotel room in Midtown with the expanse of gray carpet; and that if you want an experience like the one on offer at Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare, then put a dead fish on your kitchen table and punch yourself repeatedly in the face, then write yourself a bill for $425.29 (including wine). That should do it.

I didn’t think it would be possible to get into Masa. Masa is so oversubscribed — according to the P.R. babble — that it has a cheaper satellite restaurant called Bar Masa next door and a further satellite named Kappo Masa, on Madison Avenue, in which George Clooney ate a mere day before our visit, according to the New York Post. (In the case of anything Masa, the word “cheaper” is relative.) I don’t really care about George Clooney, but I mention this because I think Masa would like it; this is a restaurant franchise that thrives on the thick application of awe.

The Masa mother ship is next to Through Itself at the top of the Mall of Death because Through Itself is not really By Itself. They huddle together for profit, benefiting from cross-marketing; presumably they share copies of Finesse. My companion made the booking in her own name. This was, in retrospect, an error. She was promptly asked by the Masa receptionist: “Are they celebrating anything special that night?” Masa customers do not use telephones; drugged by the strange air of the Manhattan super-restaurant, I begin to think: is it possible they do not have hands?

You pull back the curtain — a real curtain from ceiling to knees, not a metaphorical curtain, and it flaps in your face, gently — and learn that the most famous sushi bar in New York looks like a shed, or a ghostly corner of Walmart. I suppose the awful phrase “the wow factor” had to bring us here eventually; when you can wow no more, go shed. When I see Masa, I understand — I applaud — the dazzling ambition of this confidence trick: two tiny rooms with beige walls and pale floors, some foliage, some rocks, a dismal pool.

The larger room holds the counter of Chef Masayoshi Takayama (“Masa”). It is brightly lit. Masa is usually described as legendary, but I dislike this word; I prefer to call him clever. This Keyser Söze of squid came from Japan to L.A. to New York on a wave of whispers, less for the manufacture of his sushi, I suspect, than for the manufacture of his profit. He has an air of great seriousness and nobility, like a man who has outsmarted life but still knows its gifts are worthless. His eyes are Yoda-wise; his movements are brief and graceful; he is wearing bright blue shoes. I fantasize that he is an actor playing Chef Masayoshi Takayama (“Masa”) while the other — the real Chef Masayoshi Takayama (“Masa”) — is elsewhere. Maybe there are three of them, one for each restaurant, and more to come, depending on demand. But I let it go. I think he is laughing. Specifically at us. He bows.

The diners sit silently, like well-dressed children taking an exam in self-delusion, which they will pass. Later, some of them will post copies of the bill on TripAdvisor; others, it is rumored, are Nobu employees wearing hidden cameras; if so, they are the world’s most ludicrous and well-fed corporate spies.

My companion and I sit in the smaller room. The table, says the waiter, is blond maple wood and surpassingly smooth; it is sanded between every service because each drip leaves a stain. I have never before met a table that thinks it is a tablecloth. There is Japanese writing on the wall. I ask the waiter: “What does it mean, this writing?” “No one knows,” he says quietly. “It is in a dialect so obscure it cannot be translated.” It is literally incomprehensible.

The arrangement of dishes is complex. I draw a diagram and look at it many times, but I still do not understand. It is as impenetrable to me as the wilder shores of Republicanism. On these dishes are tiny pieces of fatty tuna, fluke, sea bream, deep-sea snapper, squid, needlefish, seawater eel, freshwater eel. I know that it is sushi — good sushi — and rare, rich Ohmi beef, but no flesh can live up to the idea of Masa, even if it died in the act of trying.

Chef Masa comes to emit wisdom, but I miss it. I am sitting on the toilet in a room that looks like a hovel made of rock, or the set of the last act of the Lord of the Rings. (After the shed, witness the cave!) My companion relates: he came over; he shook her hand and nodded with all courtesy; the waiter asked, as if bearing some dazzling gift, “Do you want a photograph with Chef Masa?” Being of strong mind, and immune to even the more powerful narcotics that Public Relations can deliver, she declined. But she thanked him (for what, she still cannot say); and he was borne away on the golden winds of commerce, presumably to Kappo Masa and George Clooney’s mouth. The bill was $1,706.26.

As we leave, I walk to the sushi shrine for one last gawp. What is its meaning? A waiter is watching me. I move; he moves. I stop; he stops. He does not want to obscure my view; he is, so shamefully, my pliant shadow.

So this is where the money ends; this is where it flows; this is what it is for. To a fake shed with a toilet-cave and a narcissistic airport lounge on the fourth floor of a shopping mall in New York City that has risen in the early twenty-first century to service a clientele so immune to joy that they seek, rather, sadism and an overwrought, miniaturized cuisine. For when you can go anywhere, as the crew of the Flying Dutchman knew, everywhere looks the same; and so the quest for innovation goes on. This quest is neurotic, even in Manhattan, an island built high to compensate for its isolation and its limitations; an island shaped like a neurosis. Happy eating.