Pakistan’s National College of Arts, a redbrick building pushed back from Lahore’s busy Mall Road, is a somehow pleasing Orientalist mash-up built in 1875 by Rudyard Kipling’s father. The central quadrangle is surrounded by a colonnade that serves as both passageway and common room. When I visited in 2013, students leaned against the walls and sat on the floor with their laptops and phones. They were studying architecture, design, musicology, sculpture, and painting. Men and women wore jeans, kurtas, and loose sandals that made soft flapping sounds as they walked. The few women who covered their heads did so with pretty, patterned scarves. The conversations were easily, casually, coed.

Interviews with N.C.A. students and teachers were hard to arrange from New York; I wondered whether they were worried about talking to an American. Once I arrived, I realized the reason was much simpler: as on any college campus, everyone was always busy. But they were also always ready to talk. I was allowed to roam freely through the school.

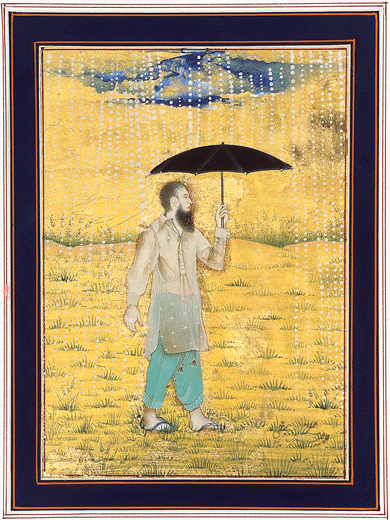

Moderate Enlightenment, 2009, a gouache painting with gold leaf on wasli paper, by Imran Qureshi. Collection of Amna and Ali Naqvi.

Lahoris think of their city as a safe place in a dangerous country, and within Lahore, N.C.A. is a special refuge. The Pakistani novelist Mohsin Hamid described it as “a microcosm of Pakistan, but a creative Pakistan, an alternative to the desiccated Pakistan.”

The beating heart of the school is the miniature-painting department. Miniatures originated in Persia and were brought to the Indian subcontinent when the Mughals conquered it in the sixteenth century. They could take on almost any subject: landscapes or portraits; stories of love, war, or play. The British were eager collectors of the paintings, which could be as small as ten by four inches and usually incorporated gold and other valuable pigments. They founded N.C.A. in part to keep the tradition alive.

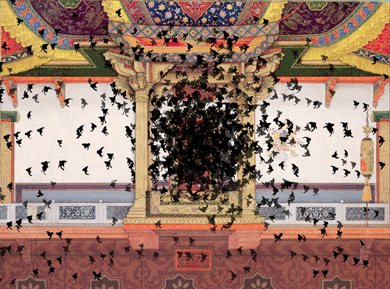

In the 1990s, a group of artists who later became known in the international art world as neo-miniaturists were students at N.C.A. Shahzia Sikander was the first among them to bring the modern miniature to the West; she now lives and works in New York. For a while, her huge talent represented the whole genre. But recently, her classmate Imran Qureshi has become equally prominent. In 2013, he had an installation on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he was named Deutsche Bank’s artist of the year. His work often includes Mughal-inspired foliage interspersed with Jackson Pollock–like spatters. A leaf that is a fraction of the size of a fingernail in a miniature painting becomes as big as a hand in his installations.

Qureshi, who is in his early forties, lives in Lahore and teaches at N.C.A. He invited me to visit his studio there, where a group of first-year students sat on big square pillows that lined the perimeter of the room. Drawing boards were propped on their laps, and their pencils and paints lay by their knees. They were drawing grids. Upstairs, in another studio, a smaller group sat in a circle. These were the third-year students who had chosen to major in miniature painting. A small set of portable speakers quietly played American pop music, and a middle-aged man from the canteen came around to take orders for snacks: chai, potato chips, cookies.

Each of the third-year students was working on something different. There were no teachers supervising them, and the room felt both more focused and more relaxed than the studio downstairs. I saw several paintings that combined traditional and modern references; one student was drawing Mughal figures inside TV screens. Most of these students had not actually seen a Mughal miniature painting in person. The British built the Lahore Museum next to N.C.A. to be a teaching museum, and there was originally a door between the buildings so that students could duck in to study original pieces. No longer. Because of safety concerns, the Lahore Museum has locked up its miniature collection and special permission is needed to see the paintings.

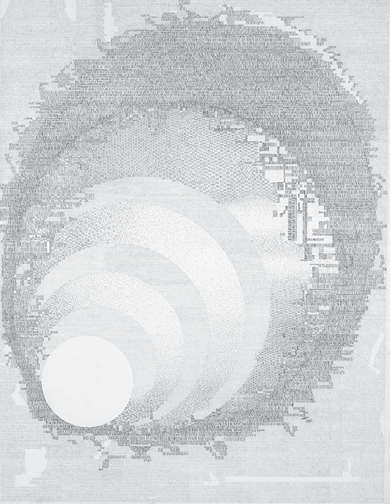

I stopped next to a student named Minahil Hafeez, who was drawing rows and rows of tiny vertical lines, a few centimeters high, in pencil. She was the only person in the room working in gray scale and abstraction. She told me that the students were busy preparing their portfolios for the thesis show that would take place in a few weeks. In the meantime, their work was being subjected to rounds of critical examinations (known here, as in art schools everywhere, as crits), in which Qureshi and the rest of their teachers would give them feedback. The next day the whole class would gather for a crit. “Come, you’ll see,” she said with a slight tilt of her head.

The next morning, there were twice as many students in the studio. Hafeez beckoned me over to sit by her and ordered me chai from the canteen man. Qureshi was one of four teachers seated at the front of the room. One by one the students were called up. There were two parts to each crit: first, the students showed their work, and then they were asked to speak about it.

The students and teachers mixed languages, often starting in English and switching to Urdu for more complicated ideas or for jokes. Qureshi generally weighed in last, and he spent more time looking than talking. When he did speak, his voice was gruff. He said little to the most promising students. When Hafeez’s turn came, Qureshi pulled out two paintings that he thought were “moving in a new direction.” And he suggested the obvious: that she start experimenting with color.

There is money in Lahore, old and new, and society. Society as it existed in New York for Edith Wharton: a small number of families whose lives are intertwined by marriage, wealth, and education. Some of these people spend money on art, but not as much as they spend on cars, jewelry, and designer clothes. Punjabis are famously, sincerely showy.

I glimpsed this side of Lahore at night, when I was invited to house parties by some of the city’s gallerists. Among the elite, there is a casual attitude toward drinking alcohol, and hash is ubiquitous, a dark, purply-brown, tarlike substance rolled into balls and kept in pockets. At one party I attended, hospitality was shown by a row of neatly rolled joints arranged on the marble countertop of the bathroom.

N.C.A. is both a part of this world and outside it. There are students who come from the Lahori elite, but they are in the minority. Tuition is less than $1,000 a year, and three quarters of the students receive financial aid from the government. There is also a geographic quota system; each province of Pakistan is represented. As the northwest part of the country has become increasingly violent, the diversity within N.C.A. has become more than geographic; it is experiential.

Qureshi introduced me to Sajid Khan, a student of his who graduated with distinction in 2012. Khan was from Swat, an administrative district near the Afghan border. It is where Malala Yousafzai was shot by the Taliban in 2012 on her way to school during her campaign for girls’ education. What Yousafzai wants for girls across Pakistan is what the female students at N.C.A. have: education, freedom, equality.

When I asked Khan about coming to N.C.A., he described it as “another country, like Australia or New Zealand, very peaceful.” He lived with two of his former N.C.A. classmates in the semi-squalor of college roommates post-graduation. When he asked me whether I would like some tea, the same middle-aged man who worked in the N.C.A. canteen appeared with a cup and smiled at me in recognition.

Khan was now working as a digital graphic artist at a gaming company and only had time to paint in the evenings and on weekends. He showed me images from his thesis show on his laptop. One had a rich, dark-blue background — the color was so deep because it has been painted in layers, on a handmade paper called wasli. The miniature was the classical Mughal size, but it was mostly abstract: in the center was a cloud in purple, fuchsia, and gold leaf; two bees hovered above it. He said the miniature depicted his family’s garden, which had been bombed.

The work had already been sold, to a local gallery called the Drawing Room (now known as Taseer Art Gallery). During the thesis show, every corner of N.C.A. is used by student artists to display their work, and everything is for sale. “It’s healthy for the students to sell their work,” Qureshi told me, “so they don’t get too attached.”

The Drawing Room was appropriately named — the gallery is an extension of Sanam Taseer’s living room. There are no public spaces dedicated to contemporary art in Lahore. When I visited Taseer’s walled, gated, and guarded house, she greeted me warmly, though we hadn’t met before. She had a slight British accent from her years at law school in England and wore Western clothes — stilettos, tailored pants, and a silky blouse. She had moved back to Lahore from New York a few years earlier.

Taseer’s father, Salmaan Taseer, was the governor of Punjab from 2008 to 2011, and he was a vocal critic of Pakistan’s draconian blasphemy laws. On January 4, 2011, he was assassinated by one of his bodyguards. Several people I met in Lahore mentioned “what happened to Salmaan Taseer,” but I rarely heard the word “blasphemy,” as if it were blasphemous to even mention it. In conversation and in the art I saw at Sanam Taseer’s house, direct references to politics were rare.

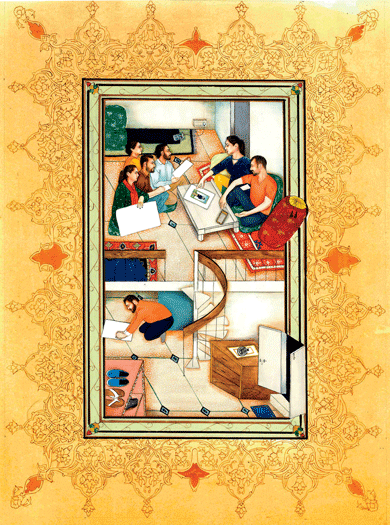

National College of Arts Classroom Critique with a Boy Burnishing Wasli, 2015, a gouache painting with tea wash on wasli paper, by Ahmed Javed.

On her walls were several neo-miniatures and a few larger paintings; most were the work of former N.C.A. graduates. Her living room was full of carefully arranged midcentury modern furniture: a Mies van der Rohe daybed, an Eames lounge chair, an Arco lamp.

“I am obsessed with Danish modern design,” she said.

“It must be hard to get here — did you bring it from New York?” I asked.

“They make them here! At the local shops an Eames chair will set you back six hundred dollars!”

Six hundred dollars — 60,000 rupees — was Taseer’s magic number: most of the art in her gallery was listed for that price. Once the artists she represents gain traction outside Pakistan, they usually find an international gallery to represent them, first in India or Dubai. Taseer is an essential link on this path out.

There is a resulting emptiness at the center of the Lahore art world: the city’s best artists can’t or won’t sell at home. The work has already been spoken for, earmarked for international fairs and shows even before it is made. With a handful of exceptions, rich Lahoris won’t pay what the international market will for art. Instead of $70,000 — which is what you might spend on a piece by Imran Qureshi if you were buying in New York — they want to spend 70,000 rupees. As a consequence, the only work by Qureshi I saw in Lahore was in his house.

Farida Batool created one of the most arresting works I found on my trip. It was a life-size photograph of a little girl in a puff-sleeved white dress standing in a field of yellow flowers. She looks straight out of the picture with a solemn gaze. Over her dress is what looks like a dark gray life jacket. It is, in fact, a suicide bomber’s vest. The nature of the medium, a lenticular print, makes the work shimmer and change, and as you walk by, the girl disappears entirely.

The day after I saw the print, at a collector’s house, I visited Batool in her office at N.C.A., where she is a professor. It was a cold morning and there was no heat. Batool drank chai out of a thermos and wore a chunky sweater that nearly swallowed her. She had the same solemn expression as the girl in the field, and I wondered whether the print might be a self-portrait. She smiled and said yes: she thought of using a model but didn’t feel right making someone else disappear. She had used a childhood photo of herself, from the summer of 1974. She remembered that time as peaceful: “We used to have our main gates opened at all times and the main doors would get locked at night only.”

Much of Batool’s recent work reflects a family tragedy: her first cousin and his son were shot while driving to school — “because they were Shia,” she said. Such targeted killings are assassinations without the celebrity, and they have become widespread in Lahore. Most people I met had just one degree of separation from someone — family, neighbor, friend — who had been killed in this way.

Batool articulated something that I had begun to suspect: that much of the best work by Lahori artists was made in response to the increasing violence in the city. After her cousins’ deaths, Batool exhibited a series of photographs about walking through Lahore called Kahani eik shehr ki (“Story of a City”). “That project helped me,” she said, “because all the anger was directed with protesting in a creative way.” In 2011, following a bombing in his neighborhood, Qureshi created an installation of bloodred foliage at the Sharjah Biennial.

While I was in Lahore, a Taliban commander was killed in a U.S. drone attack, which temporarily derailed the Pakistani government’s peace talks with the group. Batool was critical of the talks and said that negotiating with fundamentalists was impossible. I asked her whether she ever discussed politics in her classroom. She said she did, but carefully: “I say, ‘No, I don’t want to answer your question. I want you to talk about it.’ ”

She reminded me that N.C.A. is a government institution. Classes could have up to 150 students, and there were dozens of teachers and administrators. It was impossible to know who might describe something she said as too radical. And there were scary precedents. A popular teacher of English literature at another university in Punjab had been imprisoned for blasphemy, and the humanrights lawyer who took his case had been murdered.

During the decade before Qureshi and his classmates arrived at N.C.A., Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq was president of Pakistan and censorship was a national policy. But I’m told that even under Zia, who seized power in a military coup, the school was a safe haven, a place where European art books were passed around and ideas and images could be discussed with a freedom unknown in the rest of the country.

Under Pervez Musharraf, the national censorship policy was relaxed, and many artists of Qureshi’s generation who had left to pursue careers abroad returned home to work and teach. Pakistan developed a strong and critical media, which is still active today. Contemporary artists felt freer to address issues of violence, gender, and politics in their work.

Today it is the fundamentalists, not the government, who restrict speech. A few months before I visited N.C.A., Sohbet, the school’s journal, was shut down because of a charge of blasphemy by the jihadist group Lashkar-e-Taiba. The New York Times reported on the story, but the Pakistani media was eerily silent.

I asked several of the artists I met about Sohbet. No one wanted to speak on the record. Eventually someone told me what had offended the fundamentalists: the journal had reproduced a painting of a Muslim cleric and a naked boy. I was told that it was influential supporters of N.C.A. who had urged the media blackout; the story could have endangered the entire Lahore art scene. N.C.A. issued an apology for the article, shut down Sohbet, and destroyed the remaining copies.

It was unclear how Lashkar-e-Taiba became aware of an art publication that circulated among such a small group of like-minded people. Someone within the school might have leaked it, which made many of the faculty and students uneasy.

On one of my last days in Lahore, I got my hands on a copy of the banned journal. The supposedly blasphemous work does indeed show a cleric and a naked boy. They are in a market, part of a central grouping of three figures loosely based on Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe. The naked, effeminate boy looks directly at the viewer while the cleric lights the cigarette of the third figure, a clothed boy who sits between them. The article that accompanies the picture is about homoerotic desire in contemporary Pakistani art.

No one I spoke to dwelled on the obvious sadness of the journal’s being shut down. That outcome was taken in stride as politically inevitable. Instead they talked about the details: the placement at the front of the book and the size of the image (“If only it hadn’t been such a big picture”).

The word I heard most frequently about the case was “unwise.” The artist was unwise. The editorial board was also unwise. The opposite of being unwise in Pakistan is playing a careful game of self-censorship and concealed criticism. That’s why so many artists have found the miniature tradition so useful: subversive content is often overlooked when it is presented in a beloved national art form.

Before I left Lahore, Qureshi urged me to join his class on a field trip to Rohtas Fort, which was built in the sixteenth century. The drive from Lahore took four hours, and I fell asleep in the car almost immediately, despite the noise from the rickshaws, motorcycles, and trucks that surrounded us. When I was shaken awake, I looked out the window and realized we were in the country. The sky was wide and blue, and before me were towering stone walls.

Inside the gate the group climbed up to walk the ramparts. From there we could see that the fort’s walls snaked through a landscape of scrub-covered hills. I saw more goats than people. Above all, it was quiet, peaceful.

“I’ve been here maybe fifteen or twenty times,” Qureshi said appreciatively.

“Why not do an installation here?” I asked. I imagined his signature motifs curling over the crenellated walls, even nestling into the hollow stone once used for executions (the heads would drop more than a hundred feet), before running down to the land below.

“It doesn’t need it,” he replied.