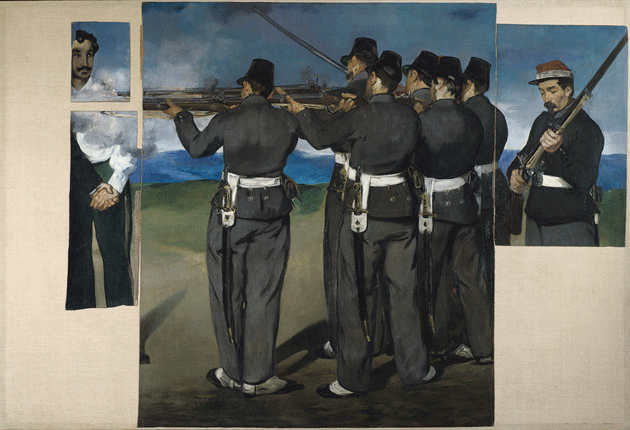

In 1996, the Libyan writer Hisham Matar was living near the National Gallery in London. For six years straight he had been going to the museum, sometimes as often as five times a week, to look at the same painting by Velázquez. But on June 29 Matar left off with the Velázquez and switched to a new painting, Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian. Years later, he learned that the day he took up his “vigil” before Manet’s depiction of a death by firing squad was, in all likelihood, the same day that his father was gunned down alongside more than a thousand others in a courtyard of the Abu Salim Prison in Tripoli.

In THE RETURN: FATHERS, SONS AND THE LAND IN BETWEEN (Random House, $26), Matar, the author of the novels In the Country of Men and Anatomy of a Disappearance, explains that Manet painted three versions of Maximilian. The National Gallery’s is incomplete: after Manet’s death, the artist’s heirs cut the canvas into pieces, which were later reassembled by Degas. The figure of Maximilian was never recovered; only his hand, intertwined with that of another condemned man, is present. “It would be hard to think of a painting that better evokes the inconclusive fate of my father and the men who died in Abu Salim,” he writes.

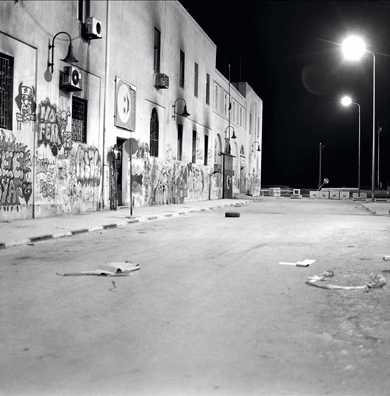

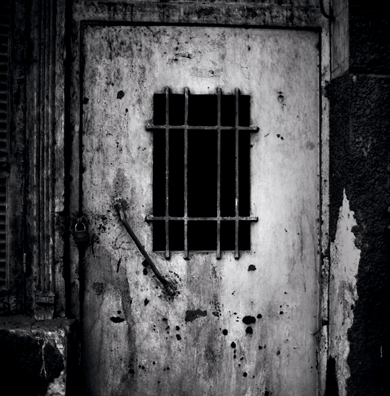

“The Entrance 13,” by Diana Matar, whose monograph, Evidence, was published by Schilt. Courtesy the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York City

Matar’s father, Jaballa, was one of the most prominent Libyan dissidents of his generation. The son of Hamed Matar, who fought in the resistance against the Italian occupiers, Jaballa was an officer in the Libyan army when Muammar Qaddafi seized power in 1969. Beginning in the late Seventies, critics of the dictator were hanged in public places or forced to make confessions on live television. In 1979 Matar moved with his mother and brother to Cairo; his father followed later. From outside the country, Jaballa, a wealthy importer, financed a training camp for rebel militias in Chad, as well as underground cells within Libya. He insisted that his sons learn how to ride, shoot, and swim; was generous to those in need; and loved poetry, especially the alam, a type of Bedouin elegy. In 1990 he was kidnapped from the family’s Cairo apartment by the Egyptian secret police and taken to Abu Salim, where the men on his cellblock could hear him reciting poems at night.

“And now a description of this noble palace,” Jaballa wrote in a letter that was secretly conveyed to his family:

The cell is a concrete box. The walls are made of pre-fabricated slabs. There is a steel door through which no air passes. A window that is three and a half metres above ground. As for the furniture, it is in the style of Louis XVI: an old mattress, worn out by many previous prisoners, torn in several places. The world here is empty.

To those who were imprisoned and tortured alongside him, including the writer’s uncles Mahmoud and Hmad and two of his cousins, Jaballa was a source of strength. “Don’t worry,” he wrote in a note he smuggled to Hmad, who was held in a different cell. “I am like the mountain that is neither altered nor diminished by the passing storms.” But once, on a cassette recording that he sent home to Cairo, his family heard him weeping in desperation.

“The Entrance 1,” by Diana Matar, whose monograph, Evidence, was published by Schilt. Courtesy the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York City

The Return is a devastating, if somewhat perfumed, work of art; its exquisite prose becomes mannered, and Matar is a little in love with the poetry of his family’s suffering. He is unable to lay to rest a loss that cannot be verified. In 2009, after receiving a phone call from a man who claimed to have seen his father in 2002, he began a public campaign to pressure the British government, which had been cozying up to the Qaddafi regime, for answers. After negotiating with Qaddafi’s son Seif, Matar managed to secure the release of his uncles and cousins in early February 2011. The timing was cruel. As a condition of their freedom, his relatives were forced, after twenty-one years of suffering, to sign a formal apology to the dictator. If Matar had done nothing they would have been released without this humiliation; the rebellion began later that month, and revolutionaries stormed Abu Salim in August, freeing all the prisoners.

“I remembered once again Telemachus’s words,” Matar writes.

I wish at least I had some happy man

as father, growing old in his own house —

but unknown death and silence are the fate

of him.

Odysseus comes home in the end. In The Return, it is Matar who goes, in March 2012, with his mother and wife, to the land of his childhood. Political violence has claimed a third generation: Matar sleeps in the bedroom of his cousin Izzo, a rebel fighter who was killed by a sniper bullet at Qaddafi’s compound. He avoids speaking in detail about the revolution’s subsequent putrefaction into civil war, saying only that “the situation would get so grim that the unimaginable would happen: people would come to long for the days of Qaddafi.” He finally accepts that his father must have died in the June 1996 massacre after he meets the former prisoner who had called him in London three years earlier. “But this is not Jaballa Matar,” he says, looking at one of Matar’s photographs. “This is not the man I saw.”

During the good years in Egypt, when his father was still with them, Matar’s mother threw lavish dinner parties. “In those days my mother operated as if the world were going to remain forever,” Matar recalls. “And I suppose that is what we want from our mothers: to maintain the world and, even if it is a lie, to proceed as though the world could be maintained.” Somewhat strangely for a book about parents and children, Matar gives no indication of whether he has children of his own. This conspicuous absence renders him not only homeless in exile and suspended in grief but frozen in time. “As long as Odysseus is lost, Telemachus cannot leave home,” he writes. “As long as Odysseus is not home, he is everywhere unknown.”

John Cassavetes, the actor and director, was also interested in if, and how, people find their way home. “Somehow,” he said in an interview in 1982, “drunk or sober or any other way, you always find your way back to where you live. . . . And when you can’t find your way home, that’s when I consider it’s worth it to make a film. ’Cause that’s interesting.”

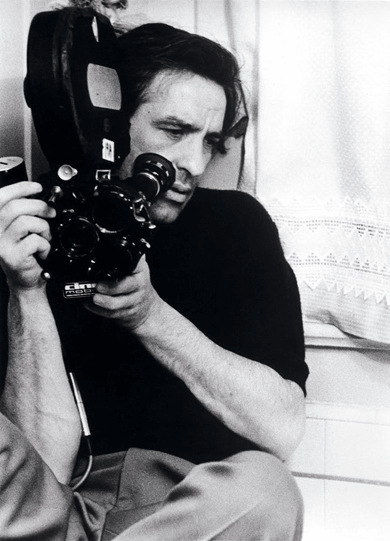

Cassavetes, of course, knew a thing or two about being drunk, including how drunkenness has a way of peeling back a person’s exteriority. In JOHN CASSAVETES: INTERVIEWS (University Press of Mississippi, $55), edited by Gabriella Oldham, it is clear that for him, filmmaking was an art of revealing human beings in their barbarous and joyful essence. Of Husbands (1970), which he wrote, directed, and starred in, Cassavetes said, “I think the picture is about people just being what they are, and that’s good enough.” He was interested in camera lenses and cinematography only insofar as they could bring out emotion; raw performance was his medium. As the critic Kent Jones has written, “Human activity is to Cassavetes what color is to Vincente Minnelli and space is to Hitchcock. It’s at once his aesthetic and his moral center of gravity, his canvas, and his most reliable tool.”

John Cassavetes in 1974, during the filming of A Woman Under the Influence © Sam Shaw/Shaw Family Archives/Getty Images

Over the nearly three decades of interviews collected in this volume, Cassavetes emerges as a brash, self-contradictory, imprecise but impassioned advocate for creative freedom and the centrality of feeling in a world of money and conformity. “If it came to a good film or what makes feeling,” he said, “I’d take feeling.” It’s a risky game to trust any artist on the subject of what their work means, and actors — Cassavetes was first and foremost an actor — are especially bad at talking about what they do. At least some of his incoherence might have been a ruse. In a television special from 1993, Peter Falk, one of his frequent collaborators, said that Cassavetes’s directorial style was “deliberately vague. He did it by keeping you off balance, so you didn’t know what was happening. So that you couldn’t protect yourself. You couldn’t use all those techniques that you were used to using.”

The power of Cassavetes’s work has to do with the environment he fostered. At their best, his films are documentaries of their own making. “I think I have one talent, as a director, to create an atmosphere where people can act naturally in the given situation,” he said. “I don’t try to control the set, which is often noisy, anarchic, the actors ganging up on me.” His films are disorderly and disorienting; emotions are often unmoored from psychology, and there aren’t plots so much as premises. The effect is at once naturalistic and surreal, a life-and-death struggle for the most elemental passions and savage intimacies.

He was famous for advocating artistic autonomy and bashing studio executives, but Cassavetes believed that autonomy could be achieved only by working with people you love. Like Bergman or Fassbinder, he collaborated with a troupe of regulars: Falk, Ben Gazzara, Seymour Cassel, and Gena Rowlands, his wife. He cast amateurs, including his mother and mother-in-law, alongside professionals. “One reason I became a director,” he said, “was that I wanted to keep my family together. It was not so much that I wanted to make films, as I wanted to make films around the people with whom I want to spend my life.”

Another person’s train of thought can be difficult to follow, even a little occult. While reading Claire-Louise Bennett’s debut, POND (Riverhead Books, $26), a series of fictional vignettes about a young woman living in a cottage in the Irish countryside, I found it difficult to pay attention in the way that sometimes, when someone else is talking, I wake up mid-nod to realize that I have absolutely no idea what she is saying. Bennett’s unnamed narrator is aware that she is likely to have this effect:

No one can know what trip is going on and on in anyone else’s mind and so, for that reason solely perhaps, the way I go about my business, such as it is, can be very confusing, bewildering, unaccountable — even, actually, offensive sometimes.

Chandelier Gold, by Lorraine Peltz. Courtesy the artist and Micaëla Contemporary Projects, Alamo, California. Middle

In Pond, the narrator does such things as clip her toenails, remember a poorly received talk she once gave about love and literature, and attempt, and fail, to replace the broken knobs on her stove. She muses about her pens, cleans the fire grate, and accidentally scares off a herd of cows. The book is an investigation of interiority, but consciousness is not its only interest. The narrator sometimes withholds the content of her thought altogether, instead directing attention to

The black trees

The tilting sphere

The humid bovine nostril

The sprawling chandelier

The thin lace trim

My damp unbrushed hair

Bennett has a poet’s appreciation of the sensorium, and Pond is attentive to food, nature, and clothing in a way that feels fetishistic or erotic. The narrator plans a party, anticipating a particular person sitting on her ottoman, and is disappointed when that person doesn’t come. “My fascination was short-lived in any case, perhaps it lasted a fortnight, less, and it was only brought about in the first place by a blouse she wore one day — the collar, to be precise. The way her head was bowed, actually, just above the collar.”

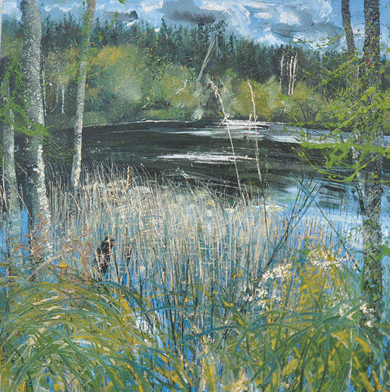

Kilvey Lake, by Neal Greig, whose work is on view next month at Claremorris Gallery, in County Mayo, Ireland.

Still, the physical world is hardly a refuge from the difficulties of language and communication: “To be perfectly honest I have, of late, become unusually disassociated from my immediate surroundings.” Occasionally Bennett’s narrator loses herself in an action, such as ironing her boyfriend’s shirts, and feels herself moving in and with the world. More often, however, the moments of profound lucidity and perpetual intensity that buoy and punctuate her existential dislocation are themselves displacing and incongruous. Pond is deeply intelligent, but despite the panic that thrums beneath the narrative, it is never gripping — I could have put it down at any point and never thought about it again. In the end the narrator finds a fragile resolution by making peace with the “monster,” an emblem of her ever-present anxiety:

And why shouldn’t I stand at the window like this? Why shouldn’t I be seen? I’m not afraid. . . . Let it stand in the moonlit lane and watch me. It’s been watching me all along, all my life . . . and I have to be doubly careful I think, not to frighten it away, because between you and me I can’t be at all sure where it is I’d be without it.