One December evening in 1987, on assignment for a glossy travel magazine to write about island resorts in the wintertime, I took cover from a sleet storm in a Nantucket tavern. Lit by fake candles, the place smelled of lemons and wet wool; bar towels sizzled on the radiators. After a period of watching water droplets connect and reconnect on the varnished surface of the bar, I noticed that the guy on my left was wearing a brown leather jacket as weathered as my own, and I remarked to him that he looked about my age.

“Born in ’49,” he said.

“No kidding,” I said. “I’m a ’49er, too.”

“Which day?”

“November twentieth.”

“Holy shit,” he said, clapping me on the back. “I was born the same day.”

This called for a toast, and we raised our glasses.

“Whereabouts?” he asked.

“New York.”

“Well, there the coincidence ends,” he said. “I was born in Brooklyn.”

“Actually,” I confessed, “that’s just my shortcut answer. I was born in Brooklyn, too.”

The drinkers around us, clearly off-season regulars, pressed in to hear more. With the wind rattling the windowpanes, we established that out of the three dozen or so hospitals operating in Brooklyn in 1949, this hippie carpenter and I had been born an hour apart at the same one: Brooklyn Jewish, which no longer even existed, having gone bankrupt in 1979. Improbably enough, we had shared the same neonatal nursery, bawling and fussing within earshot of each other, enjoyed our far-flung adventures, then reconvened nearly four decades later on this island thirty miles out in the Atlantic, both drinking the house red.

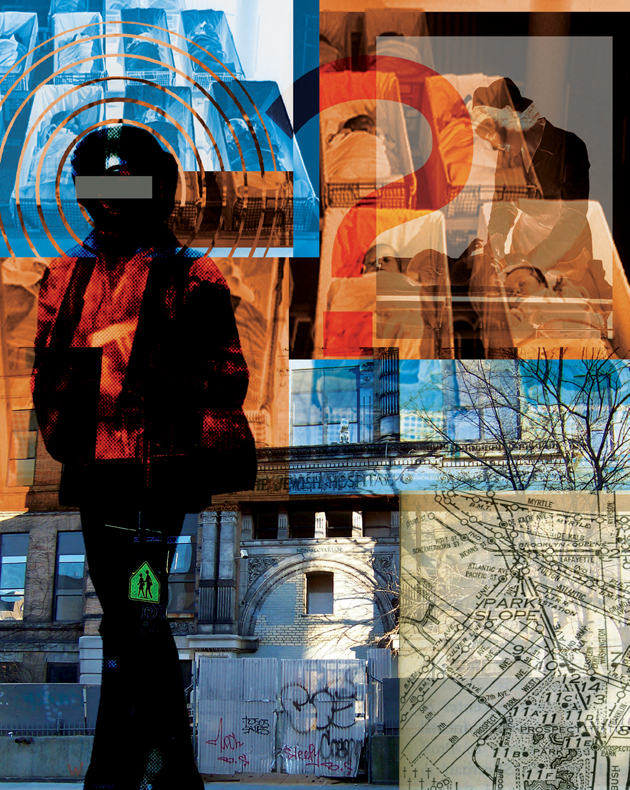

Illustrations by Darrel Rees. Source photograph of nursery © Mirrorpix/Newscom; postcard of the Jewish Hospital of Brooklyn, bottom left, courtesy the Brooklyn Historical Society

The bartender stood drinks all around. For everyone in the place, it was as if a spotlight had pierced the gloom, illuminating us as birth mates, our origins joined in a kind of double horoscope of time and place. Everyone grasped at once that it wasn’t the fluke itself that was so amazing; it was that we had discovered the fluke, instead of merely continuing to rub elbows in the dark. And the similarities kept on coming. Within a few minutes, the carpenter and I discovered that we had married and divorced within a few months of each other, had our first children within five days of each other, and both had one son named Jeremy.

Hey, coincidences happen. I let it slide. I left the bar and the island, published my travel piece, and allowed the incident to fade from my mind. Grass grew, leaves fell, it sleeted anew. It wasn’t until a decade and a half later, middle-aged and sobered up, that I found myself thinking about that night in Nantucket, wondering exactly how many degrees of separation there were between that hippie carpenter and me. It gave me an idea. Why not track down the other kids from my nursery? Who were they, and what had this interestingly randomized group been up to for the past, oh, half century?

Imagine, if you dare, a world before fast food. An era when Americans labored for forty cents an hour, and it was common for restaurants in the nation’s capital to refuse service to black people. When nearly one quarter of all U.S. farms still lacked electricity, a loaf of bread cost fourteen cents, women were not yet admitted to Harvard Law School, and the last of the Confederate veterans were assembling in Arkansas for one of their final reunions.

This was the United States in 1949. Stupefying as it may sound, the McDonald’s empire consisted of a single outlet in San Bernardino, California. The phrase “under God” had not been inserted into the Pledge of Allegiance. There were no hydrogen bombs, human organ transplants, or panty hose. The polio vaccine had yet to be developed, and M&Ms were still naked. (They weren’t stamped with letters until the following year.)

As for New York City, it was a place “filled with river light,” as John Cheever wrote, where “you heard the Benny Goodman quartet from a radio in the corner stationery store, and [where] almost everybody wore a hat.” By the East River, the gleaming slab of the United Nations headquarters rose floor by floor, designed to ease the international birth pangs of Israel, Vietnam, Jordan, and Communist China. Automated elevators were a rarity, and Ellis Island still had a Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital to screen questionable immigrants. The metropolis glowed from within, a kind of postwar sunburst, even as it released its middle class like rays of light, thanks to a Brooklyn boy named William Levitt, who more or less invented the idea of suburbs by stamping out tract houses at a rate of one every sixteen minutes.

On one particular day — November 20 — the city was girding itself for three events. There was the Carnegie Hall singing debut of the president’s daughter, Margaret Truman; an impending visit by the thirty-year-old shah of Iran (deemed an “attractive young man” with a “real grasp of public affairs” by that morning’s Brooklyn Daily Eagle); and the opening, the next day, of a show by a rising Abstract Expressionist named Jackson Pollock. The air was breezy and mild. Indeed, the weather had been so dry that before the winter was over, city administrators would take the unprecedented step of hiring, for $100 a day, an official rainmaker.

In one particular corner of the city — the middle-class enclave of Crown Heights — a group of babies was being born at the Jewish Hospital of Brooklyn. (Despite the name, the word non-sectarian appeared above the door at 713 Classon Avenue.) It was a good hospital. Albert Einstein had chosen to have an exploratory laparotomy performed there one year earlier. Still, there was no way to know whether any of the newborns lying within wailing distance of one another that day would be extraordinary or accomplished in any way.

As it happened, the horoscope in the Daily Eagle suggested otherwise. “Your own originality is often subservient to the wishes of others,” it warned the newborns. Chances were, then, that they would exemplify the miracle of ordinariness. They would be bottle-fed rather than breast-fed, vaccinated with resharpened needles (disposables had yet to be invented), placed in adjacent steel bassinets for a standard hospital stay of seven days (at a daily cost of around ten dollars), then inserted into the midcentury to begin their commonplace lives.

I began my first round of investigations in 2003. Guardedly optimistic, I planned a trip to Interfaith Medical Center, which had swallowed both Brooklyn Jewish and another hospital in a 1982 merger, to examine the old records. I visited the microfilm section of the Brooklyn Public Library to pore over the Daily Eagle. I placed ads in numerous periodicals and on websites and, having heard that the Mormons kept meticulous birth records, I contacted their Family History Centers as well. I ran down retired hospital officials to see if they had kept files, examined libraries of various medical societies to get names of old obstetricians, and flipped through faded nursing magazines.

Nothing worked.

The records of Brooklyn Jewish were mostly destroyed following the 1982 merger. (“When we closed the building, our effort was to get rid of unnecessary papers,” former Interfaith CEO Michael Kaminski told me.) Strict new privacy laws, enacted just a month before my search began, guaranteed that any records that did survive would be kept under lock and key. The Daily Eagle of 1949 published nearly everything — death notices, marriage licenses, bowling scores, sermon topics, dates of upcoming mothers’-club teas, dog-show results — but not a single birth announcement. The Mormons got so tired of my emails that they stopped responding. I received exactly one response to all my ads, from a lawyer who wanted to know if I was spearheading a class-action suit.

Source photographs of New York City birth records from 1949 by the author; source photograph of nursery © Everett Collection/Newscom

Getting nowhere, I figured it was time to sift through the raw data. At the Office of Vital Records, on Worth Street in Manhattan, I lugged down two volumes of a 1949 logbook: more than two thousand double-column pages of births, undifferentiated by hospital. I spent long, boring days running my index finger down all 156,932 entries, separating out the estimated 54,946 babies born in Brooklyn. From these I culled a smaller set born on the date in question, then culled some more through serendipitous online research, until I had narrowed it down to just a couple hundred phone numbers. It was time to start cold-calling.

Dozens of false leads and tantalizing near misses followed. Because they turned out to have been born on the wrong date or in another Brooklyn hospital, I was forced to discard the scion of a family that owned the Coney Island Wonder Wheel, a denizen of the Las Vegas underworld whose brother advised me to stay clear, the dean of a Connecticut prep school, an actuary who turned out to live five minutes away from my Massachusetts farm town, and a Special Forces operative whose entire personal history had been expunged so thoroughly that even his ex-wife didn’t know his real birthday.

At last I hit pay dirt. Over the course of several months, I made contact with five birth mates. We emailed, talked on the phone, had some preliminary visits — and then, to my own surprise, I let it drop. Despite my initial eagerness to pursue the project, it felt like the timing was wrong. They were in the middle of stuff, I was in the middle of stuff, and an air of incompletion hung over our conversations: it was too early to see our lives whole. The investigation went onto the back burner for more than a decade.

Then came the winter of 2014, when we all turned sixty-five. We had reached the traditional entry point to senior citizenship, and although financial uncertainty and Viagra had rejiggered the definition of old age for many Americans, I felt we had advanced far enough for some deeper perspective. We were also at the end of our life expectancy, which was just a hair over sixty-eight — according to actuarial science, we were more or less done. I found myself wondering anew about my birth mates, and about my generation itself. Ten thousand of my contemporaries were reaching retirement age every day. The moment had arrived. And so, the following summer, I went to see them for real.

My drive up the Maine shoreline in June 2015 was uneventful. I got a speeding ticket that cost me $219, and chided myself for still being a reckless driver at my age. Halfway up the coast, I turned off the highway at Searsport and proceeded down a gravel road to a tidy little castle fronting upper Penobscot Bay.

This was the summer house of David Italiaander. When I had visited him in New Jersey in 2003, he had been a bit standoffish, wondering whether there was some private agenda behind my quest. This time, however, he greeted me with open arms the moment I stepped out of my car.

“You couldn’t find something a little closer to the water?” I said.

He laughed, comfortable with his prosperity. As an osprey flew overhead with a fish in its claws, Italiaander guided me inside to an enclosed sun porch with wicker chairs. There we sat as he summarized his life for me, beginning with the Sunday when his mother went into premature labor and delivered a baby weighing less than four pounds — a risky proposition in those days, when many preemies went blind as a result of the oxygen indiscriminately pumped into their incubators. The details kept coming, and my host, genial and alert, seemed to relish the narrative. He had avoided the draft and Vietnam, just as most of our group had, sharing the same high lottery number of 185. His role in the student protest movement at his college had been twofold: he helped to take over the dining hall and cheered when his roommate furtively slipped some acid to the local ROTC recruiter. I learned about his career in commodities, trading fats and oils — the former campus revolutionary had gone to work for Unilever, the giant multinational and margarine purveyor to the entire planet, before starting his own consultancy. He still liked Led Zeppelin. His twenty-six-year-old daughter was teaching English in Tokyo. He had recently joined with neighbors to fend off the placement of a 22-million-gallon propane-storage tank in Searsport — as tall as a fourteen-story building, it would have been the largest such facility on the East Coast.

“Still fighting the good fight,” he said.

As I listened to him — sturdy, successful, still a bit of a rascal — it was hard to believe Italiaander was once a fragile preemie, unlikely to survive. But he seemed eager to look back and take his victory lap, and I wondered whether this triumph felt not only personal but communal.

“It seemed like our generation always had a sense of itself as a cohesive entity,” I said.

Gazing out over the waterfront, Italiaander nodded in agreement. “I certainly feel it, as strongly now as in college,” he said. “It’s a curiosity. We shared the major events: the assassinations, the Beatles on Ed Sullivan, the moon landing. We watched the same TV shows as kids. Maybe it goes even further back than that — as far back as we can trace it.”

This seemed as good a moment as any to trot out a crazy little theory I had dreamed up while researching late-Forties parenting techniques. Consider, I told Italiaander, how deliberately newborns of the era were isolated from their parents. Exhausted mothers were cautioned to limit the time they spent with their newborns — and the time they did share was clouded by the lingering effects of heavy anesthesia, which had transformed labor into a nonevent for many of them. Fewer than one in five mothers breast-fed their babies back then, fearing the effect on their figures. Indeed, one in six mothers didn’t even touch her baby the entire first week, but contented herself with viewing the infant through the nursery windows. As for the fathers, only one in seven glimpsed the baby more than once before “it” was brought home.1

Source photograph of the former Brooklyn Jewish, bottom left, by the author; source photograph of nurse with infant © ClassicStock/Alamy

By contrast, I went on, consider what transpired between the newborns themselves. During this unprecedented boom, their bassinets were often separated by no more than six inches, at least in metropolitan hospitals, and for the next week, they spent virtually all their time breathing the same air together. Fresh out of the womb, reading each stimulus as a key to the universe, they produced one another’s primal sounds, sights, and smells. Could that at least partly account for the sense of mutual attachment that has been a hallmark of the boomers? “I told you it was crazy,” I said. “But was Woodstock thus imprinted in the nursery?”

Italiaander studied me with a peculiar expression, as though I might be nuts but he didn’t mind. All part of the fabric of life. “Well, I was in an incubator those first two weeks,” he said. “But what the hell, it’s no crazier than a lot of things I could name.”

One of his five cats wound itself through his legs. Outside the windows, the bay was brilliantly clear, its whitecaps bright with promise. Hard to believe thunderstorms were predicted for later that day.

“Final question,” I said. “What happened to the ROTC recruiter with the acid?”

“Oh, he took it in stride. Apparently it wasn’t the first time. He recognized the symptoms right away and checked into the local hospital.”

“Happy endings,” I said.

“So far, so good.”

Italiaander’s words echoed in my ears as I took the train down to D.C. a few weeks later. Life had been good for our generation, hadn’t it? We enjoyed quite a run — the question was whether we deserved it. This was what I hoped to ask Peggy Ellen, born at Brooklyn Jewish just a few hours before me.

In many ways, she struck me as the perfect person to ask. The offspring of Polish Holocaust survivors, members of the Warsaw intelligentsia who had spent four years in German resettlement camps before emigrating to the United States, she had imbibed a sense of the world’s inequity practically with her mother’s milk. When she was a child, her parents Americanized the family name (“The locals had trouble pronouncing ‘Elenzweig’ ”) and opened a mom-and-pop grocery store in Atlanta. There Ellen observed the desegregation of the public-school system during the early Sixties, accomplished by dint of legal pressure but without the chaos and violence that attended similar efforts in other parts of the South.

It was, she suggested, a formative experience. Ellen went on to a career as a federal prosecutor, concentrating on white-collar fraud. She rose to become chief of the Economic Crimes Unit of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, spent eight years at the SEC, and is now deputy special inspector general for SIGTARP — the federal agency charged with investigating crimes related to the 2008 financial crisis. Ellen estimated that, as a result of her work with SIGTARP, more than a hundred bankers had been charged; at least thirty-five of them have already been put behind bars. This was a surprise to me, since I had assumed that most of those crooks got off with no more than a slap on the wrist.

“These people should be held accountable for their misdeeds,” she told me, looking over the fifty daffodils that had just finished flowering in her yard. She had planted them herself, she said, on her hands and knees, although she now had a gardener to help with such tasks. “Advil makes me feel eighteen,” she noted. In fact, Ellen herself looked in full bloom — a fox, as we used to say in our innocent political incorrectness, who had filled out and avoided the sunken eyes that had stamped so many of our mothers with a look of surprise or hurt or defeat.

I followed her into the living room of her spacious 1905 Victorian, where she stoutly defended the bona fides of the boomers. “We were a massive force from the beginning,” she said, “changing how people thought about Vietnam, the environment, civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights, endangered species. So many things.”

“So we’ve kept those noisy promises we made in the Sixties?”

Ellen laughed and stroked the head of her Samoyed, who was shedding white hair all over my black jeans. “Probably not,” she allowed. “The world still has problems.”

“How do you answer the charge that we hogged all the good stuff and left slim pickings for the generations to follow?” I was thinking of the frequent complaint that boomers have depleted Social Security, clogged the labor market by refusing to vacate jobs, profited from a huge rise in real-estate prices, and so forth.

“Some of those charges are true enough,” Ellen said. “We presided over the invention of junk bonds and the unprecedented concentration of capital in the hands of a few.” In other words, many of the people that she had fined and imprisoned at SIGTARP were fellow boomers, playing both sides of the game as usual. Her work was not only a blow struck against financial malfeasance but an act of generational housecleaning.

“Did some of us sell out? Of course. But one of the main things we did accomplish was to transmit our ideals to our kids, who have fewer visible prejudices than we did.” I followed her gaze to a photo of her two children, a lawyer and a teacher, both of whom looked idealistic enough. “We’re Scorpios,” she said, adding that we were an optimistic lot but not explaining the mystery of how such optimism could be maintained into one’s seventh decade.

Howard Wiedre had taken a more circuitous route to the kind of activism that Ellen considered the identifying characteristic of our generation. Born into an Orthodox Jewish family of working-class immigrants, he spent his first ten years getting “beat up a lot” — first in Brooklyn and then, after his mother died and his father married a “stingy, withholding” woman, in the Bronx.

“Jews weren’t well liked there,” Wiedre told me, recalling the torments inflicted on him by Italian gangs. Though strong for his age, he never really thought of defending himself until the Six-Day War of 1967, when Israel defeated the Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian armies. “Wow,” he remembered thinking, “Jews fight!” The eighteen-year-old began reading everything he could find about Israel, learned karate from a Korean master, and got involved with the Jewish Defense League, whose ultra-Zionist leader, Rabbi Meir Kahane, favored immediate Israeli annexation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Wiedre became the head of the J.D.L.’s Bronx chapter and a protégé of Kahane himself. At a summer camp in upstate New York, he received paramilitary training and learned to shoot a rifle. Back in the Bronx, the J.D.L.’s encounters with Puerto Rican gangs and the Black Panthers increasingly turned into street battles. One night, on his way home from karate practice, Wiedre was arrested for carrying a sack of nunchakus. This experience caused him to begin wondering about the direction of his life.

The turning point came not long after. “We were marching through Harlem in our J.D.L. berets,” he told me, “and the Panthers came out with pickaxes. All hell broke loose. A ten-year-old black kid jumped into my arms to slug me. It was a defining moment, because the kid was cute and I thought to myself, This is not what I want to do. I put him down and started to turn my life around.”

Wiedre married and moved to California, where he earned two advanced degrees in education. He still believed it was his duty to transform society, but he applied neither the paramilitary techniques he had learned under Kahane’s tutelage nor the legal tools that Ellen used to chase down white-collar offenders. Along the way, he started a chain of tutoring centers for students with learning disabilities. “Renovating a kid is my chief satisfaction in life,” he said. “I’m a fixer.”

“Why is that?”

“Because I was broken and fixed myself. Where I was raised, you fixed yourself or you ran into trouble. A lot of people from Brooklyn and the Bronx didn’t, and wound up dead or in jail.”

The chain was a success. Wiedre now lived with his wife, a psychiatric nurse, in a million-dollar house on a suburban cul-de-sac in Carlsbad. He was still adept in the martial arts, with black belts in three different styles, and had hardly left Judaism behind: in 2009, he set up a short-lived blog to scold 60 Minutes for its coverage of the Middle East stalemate. (“You had better believe that the Jews want peace,” he declared. “I support giving the Palestinians their own state.”) Yet his views on these issues had become more mellow and reflective, and during our conversation, he spoke of building bridges with the Islamic community — a sentiment that would have struck him as anathema during his J.D.L. days.

He had been lucky, I suggested. But so had we all. We were the beneficiaries of an extraordinary number of gifts, which the world conferred on us before we even knew we needed or wanted them. Television arrived just as we reached the age to enjoy it, and the same could be said of LSD, birth control, soul music, bell-bottoms, antibiotics, frozen foods, and so much more — the entire panoply of cultural and consumer pleasures that had fallen into our laps. We bought our first houses before prices skyrocketed, sowed our wild oats before AIDS, raised our families before the age of terrorism. Forging our values in an era of spectacular growth and unlimited expectations, we were allowed to dream big — indeed, as the recipients of such largesse, it would have been almost churlish to do otherwise. We lived in blessed times, as did the younger boomers who followed, and became the richest cohort in history. Weren’t we arguably the luckiest generation?

“Catchy,” Wiedre said when I suggested the idea to him. But he reminded me that our blessings had not been equally distributed, that our youthful euphoria had been part of a zero-sum game. During the boomer heyday, black Americans were fighting an uphill battle for the most basic civil rights, and 9 million U.S. soldiers were doing our dirty work in Vietnam. “They had to make their own luck,” Wiedre said. “If they made it at all.”

So what about the original guy I met in the bar that night? Downtown Nantucket, with its cobblestones and Greek Revival gems, looked much as it had in 1987, when Rob Andersen and I had our chance encounter. For that matter, it looked very nearly as it did in the mid-1800s, which made it a fitting place for a game of chronological catch-up. It was pouring rain, the streets were jammed with tourists, and Andersen and I approached each other in a crush of umbrellas. Looking weather-beaten in a sweatshirt and yellow slicker, he walked me past the defunct bar where we’d first met and led me to a chowder house. There he took quiet command of the conversation, his refined delivery at odds with his rumpled appearance. I couldn’t help thinking that with his long, pewter-colored hair parted in the middle, he resembled a slightly disheveled Founding Father.

Andersen came from a Norwegian seafaring family. In the 1880s, his grandfather had been recruited by the U.S. Navy to wire the boats in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. On a patch of farmland not far from where Brooklyn Jewish would open its doors in 1906, the patriarch built himself a three-story stone house — what his grandson called “your basic little mansion.” Andersen himself was raised on Long Island. After studying history in college, he played drums in a series of rock-and-roll bands, and then took up an even more quintessential boomer pursuit: collecting driftwood on California beaches to serve as bases for those Seventies-era glass-topped coffee tables. Moving to Nantucket in 1977, he took an interest in old architecture and became a master carpenter, helping to restore Main Street to its former glory. And, like his grandfather, he built his own house.

“May I see it?”

Wordlessly leading me to his pickup in the rain, Andersen drove across the island to his house, a low-lying structure tucked away in the dunes. With the help of his wife, Sybille, a professional midwife, he had built the place with exotic Indonesian timbers. The same material was used for the furniture: swooping chairs and soaring bedframes he carved himself. A Zen-like tranquility adhered to every board.

It was contagious. By the time he drove me back to town an hour later, I was uncharacteristically calm. Calm and a bit freaked, both. The sun had come out, so bright we had to squint, and we lingered a while on a wooden bench in a playground, shaking our heads at the spooky synchronicities. Not only were the dates of our milestones nearly identical (marriages, divorces, children’s birthdays), but we had both bought Massachusetts property for the same amount of money, owned a hundred-year-old Steinway Model M grand piano, and totaled three cars in successive crashes. The longer we talked, the more parallels appeared — just as they had in meetings with my other birth mates. I felt unsettled, like one of those early Victorian scientists who sensed the existence of evolution before it could be named or germs before they could be seen. I didn’t want to be like one of those folks lost in the woods who sees a human face in the bark of every tree trunk, deducing patterns where none exist. But neither did I want to brush off the phenomenon as New Age dross simply because it was outside my comfort zone. A child of my time, I wanted to believe something, but also didn’t.

“I know why you’re doing this,” Andersen said, so softly I had to lean closer.

“Tell me, please.”

“You’re crazy, of course. Like I am. Like a lot of us are. Not psychopathic — good crazy.”

I shifted on the bench. “Go on.”

“You’re interested in what connects Homo sapiens,” he said. “You grasp the plain, astronomical truth that we’re on a microscopic pebble hurtling through space at sixty-seven thousand miles an hour — and in a very real sense, connecting with one another is the only thing that matters. You were reminded of that fact when you bumped into me at that bar. Something clicked in you, and it’s taken a bunch of years, but you decided to investigate.”

I let this sink in for a minute. “What do you make of our bumping into each other in the first place?” I asked.

He had no answer. We shrugged and prepared to separate. As we did so, we noticed a plaque on the bench, commemorating the birthday of somebody born on November 19. With all the flukes flying around, the date being one day off came as a distinct relief.

“You don’t believe in fate, destiny, all that, do you?” I asked.

Andersen paused, framing his thought.

“I believe in everything,” he sensibly replied.

Does it mean everything or nothing to be part of the same generational cohort? My brief encounters with Italiaander, Ellen, Wiedre, and Andersen suggested that the moment of our birth had indeed shaped us in some crucial way: there was, at the very least, a kind of idealism to us all, although it had been diverted into very different channels. But unlike Andersen, I don’t believe in everything, and my skepticism kept rearing its head. I wasn’t, of course, the first person to ask these questions. Back in 1742, David Hume noted that human beings were born and died in ragtag formations. Society would be very different, he argued, if entire cohorts vanished at the same time. That way, the political slate could be wiped clean, and we wouldn’t be stuck with the ramshackle arrangements dreamed up by our parents. “Did one generation of men go off the stage at once,” Hume wrote,

and another succeed, as is the case with silk-worms and butterflies, the new race, if they had sense enough to choose their government, which surely is never the case with men, might voluntarily, and by general consent, establish their own form of civil polity.

Hume was being speculative. He knew that human society, unlike that of silkworms or butterflies, “is in perpetual flux, one man every hour going out of the world, another coming into it.” But that didn’t stop subsequent thinkers from pursuing some kind of generational theory. The most conspicuous, perhaps, was the philosopher Karl Mannheim, who wrestled with the question in his essay “The Problem of Generations” (1923). Like Hume, he acknowledged that human beings lived and died in a revolving-door fashion, with no neat division between cohorts. Yet he thought that generations were significant — and that what unified their members, entirely apart from the accident of chronology, was that they were galvanized by the same great historical events. During the Napoleonic Wars, for example, the peasant, tradesman, and urban loafer alike became part of the same cohort. Or so argued Mannheim, in the mildly impenetrable prose favored by Mitteleuropean sociologists:

Individuals of the same age, they were and are, however, only united as an actual generation insofar as they participate in the characteristic social and intellectual currents of their society and period, and insofar as they have an active or passive experience of the interactions of forces which made up the new situation. At the time of the wars against Napoleon, nearly all social strata were engaged in such a process of give and take, first in a wave of war enthusiasm, and later in a movement of religious revivalism.

Mannheim took a sociological tack, seeking out the spiritual affinities in any given generation. Others have approached the problem in a more scientific manner. In England, there is a long history of cohort studies, stretching back to the Victorian era. In our own day, British researchers launched a series of longitudinal studies, whose data-collecting frenzy begins practically at the moment of conception. A recent phase, initiated in 1991, assembled 1.5 million tissue and fluid samples from more than 14,000 children, including urine, plasma, milk teeth, placenta, and even stray bits of umbilical cord. A similar project, the National Children’s Study, was authorized in the United States in 2000. But fourteen years later, after enrolling 5,700 subjects at a cost of $1.2 billion, the whole enterprise was shut down in the face of budgetary and managerial acrimony. (One disgruntled N.I.H. official compared the study, with its multiplicity of goals and procedures, to a “Christmas tree with every possible ornament placed upon it.”)

For my purposes, of course, milk teeth and umbilical bits are beside the point. I’m more interested in the intangibles: the psychological and spiritual adhesives that bind us together. That puts me back in Mannheim’s camp — and indeed, his ideas have been revived in recent years by the demographers Neil Howe and William Strauss. Not only do generations exist, they argue in such books as Millennials Rising (2000), but they flourish and perish in a very specific cyclical pattern. The authors refer to these successive cohorts as idealists, reactives, civics, and adaptives. According to their scheme, my birth mates and I are idealists. That makes sense to me: I’ve already noted our shared attraction to social transformation, sometimes as a specific goal and sometimes as a will-o’-the-wisp, which lends a greater significance to our lives than they might otherwise enjoy.2

Which is it, then? Meaningful or meaningless? It’s hard to draw such conclusions with the data on hand: my birth mates and I do not a generation make. To be even minimally representative, we would need a Midwestern C.P.A. with Lyme disease, a gay waitress, perhaps a war hero. Yet it would be wrongheaded to pretend that this subset of mostly privileged people signifies nothing at all. We do have more than a bit in common. As I suggested above, we still see our youthful ideals as worth believing in, even though we’ve had to make adult accommodations along the way, many of which might have struck our youthful selves as craven and conventional. We tend to see the glass as half full. (“Cynically optimistic,” as one of us put it.) We’re settled in our houses, loyal to our pets, healthier than our parents were. We are startled by the passage of time and even more startled by realizing that, having passed age sixty-five, we’ve been alive for more than a quarter of the nation’s history.

So here we are, having just turned sixty-seven: a hippie carpenter, a commodities broker, a federal prosecutor, a radical education reformer, and a writer, all originating from a single delivery room in the middle of Brooklyn. Are there more conclusions to draw? Probably — but I can’t, or won’t, for a simple reason. I’m missing an important part of the story. One of us, a vital member of our cohort, declined to see me when I was making my rounds in the summer of 2015.

Back in 2003, Nicole Parry had not been reluctant in the least. Quite the opposite: she was more excited than any of the others. “Hm, hm, hmmm, I’m telling you,” she murmured in a singsong as I explained why I was calling. “I wasn’t even going to answer the phone just now, but something told me, You better pick that up.”

The next afternoon, I emerged from the Brooklyn subway into ten-degree weather — so cold that people were walking around unaware that their noses were dripping. The Franklin Street neighborhood around Brooklyn Jewish looked iffy enough that I asked a passerby whether it was safe for me to proceed by myself. “Aw, man,” he said, pained by the question, “you’d be safer than I’d be in your neighborhood.”

Parry called. “Stay there and I’ll meet you,” she said, not wanting me to come to her apartment. A minute later, a whippet-thin black woman was waving at me, bundled up to her chin in a knee-length dark parka, with gray wisps of hair escaping from beneath her bandanna. We came together in a warm hug, but just as suddenly, she pulled back and seemed to withdraw into herself.

As we moved down the frigid sidewalk, I sensed her struggling. The bond between us was immediate — we shared the same manic energy — but so was the tension: the situation was at once natural and completely artificial. On we walked, proceeding past African hair-braiding salons, an old synagogue that had been converted into a pawnshop, and a derelict arcade called Saviors Game Room.

And there it was, the old Brooklyn Jewish, now dilapidated and fenced off by sheets of plywood crowned by coils of razor wire — a glorious relic, whose bricks were lit up orange in the slanting sun. It was undergoing renovation into private apartments, and as we watched, workmen chucked debris out a third-floor window with snow shovels. Parry studied the scene and agreed to sneak inside with me. We squeezed through a gap in the plywood and entered the old lobby, whose ceiling was dripping water. Dust coated an old portrait of a white-bearded Orthodox Jew holding a prayer book. A construction worker peeing in the corner shouted in Spanish but made no attempt to stop us as we ascended a staircase jungly with dangling wires. Several flights up, we found what we were looking for: the remains of the maternity ward and nursery, a gutted expanse with a pigeon flapping through it. There we stood, the elevated S train rumbling by outside, while Parry told me pieces of her history.

Her parents, born-again Christians whose life revolved around the church, had left Barbados and St. Vincent in the 1940s and settled in Brooklyn, where her mother found work as a telephone operator. Dyslexia blighted Parry’s childhood. It made school especially challenging, and she often played hooky, riding around the city on the subway, visiting art museums, collecting stamps. She quit school in the eleventh grade, returning later to obtain a G.E.D. She had a son out of wedlock at age twenty (though she initially told me she was childless), became a History Channel aficionado, and worked a succession of jobs, including a clerical gig at the records department on Worth Street, where I had done the bulk of my research. At the moment, she was employed as a health worker, visiting outpatients in Queens. But after offering these details, she would divulge nothing more. In fact, she seemed to regret sharing even that much.

“I’m just private,” she said, as another contingent of pigeons began cooing on the other side of the room. “I clam up about myself.”

“Do you not trust me?”

“I’d like to not trust you, but I do,” she said: a curious locution. “I just feel I’ve said enough.”

And so it stood. I guessed that she was one of the many economically disadvantaged black children born in Brooklyn Jewish, which had a generous charity policy. I knew that she felt herself to be the product of Sixties values, just as my other birth mates did — she had marched against the war in Vietnam, and believed in nurturing those more vulnerable than herself. I was hoping, when I contacted her a second time, to learn much more. Had she gotten a college degree? Did she still watch the History Channel? How was her son doing?

When I called, however, she sounded alarmed. “How’d you get this number?” she cried out, quickly cutting off the conversation. I tried a few more times, with no better luck. It was the fright in her voice that persuaded me not to press the issue.

I can only speculate as to why she wouldn’t talk to me. The first time, she had been very curious about the others — more curious than they had been — and I’d gotten the feeling that she was measuring herself against them. Maybe I’m mistaken, but had she ultimately recoiled because she felt ashamed that they had traveled the globe and she still lived within five minutes of the place where we were born? (When I told her the story of meeting Andersen in Nantucket, she wasn’t sure where Nantucket was.) If she felt that her life had been meager in comparison, I wish I could disabuse her of that notion. Given what she had been up against, she was in many ways the most accomplished of the six of us. But the connection had been broken, and my reassurances, which she probably would have found condescending in the first place, would not be delivered. Her absence leaves a hole in this story, a vacancy, which nonetheless completes it.

What happens now, nearly thirty years after I bumped into the first of my “lucky” birth mates in a Nantucket watering hole? Do I check in ten years hence, or organize a wheelchair-based reunion when we hit the century mark? Having reentered these stories in medias res, I’m reluctant to let go of them, but also unsure how best to proceed. A reunion — all of us in the same room, breathing the same air again for the first time in nearly seven decades — might have the effect of slowing down time. Or not. In any case, it would serve to remind us of a simple truth: at every moment of every day and night, in hospitals around the globe, miraculously ordinary people are being born.

Other than that, the only thing I know for sure is that I want to give my birth mates something to commemorate our shared connection: a humble token of our common origins. I had found just the right souvenir during my stealth visit to the hospital in 2003. I thought I had lost it, then located it again this past summer, tucked away in the sweltering attic of my Massachusetts farmhouse: a twelve-by-twelve-inch square of gray linoleum that Parry and I had peeled off the floor of our nursery. I would cut it into six rectangles. Placed in plain frames and mailed regular delivery, they might be worth keeping a while.