In the early 1980s the Southwark side of the River Thames was a wasteland. It had a power station with a tower — a rude finger — for emphasis; you, it says, are screwed, in bricks. The power station is now an art gallery with a loathsome and illiterate name, a legacy of the Blair years and its love of spin: Tate Modern. Next to Tate Modern is the Globe Theatre, a tiny building sitting, I think, in expectation of being crushed. It has the intelligence to look vulnerable, and it is. I went to a twenty-first-birthday party there years ago, when only the foundations had been built. It was nighttime, and my date and I walked down to the river mud and kissed. Ten years later, I met a girl sleeping under Waterloo Bridge, half a mile upriver. She was a runaway; her name was Kimberly. Her hair was blond, her eyes bright with heroin. She was twenty-one years old. Within a month the streets had killed that child. I went to her sad and speechless funeral in Willesden, to the north.

London is now a hollow town, much like New York City. It is not the city that I sought in the river mud, the city that I looked toward as Oz. It is not content to live on its own level, or in its own day; it flies upward and downward. It has become incoherent, an addict seeking space. The rich buy palaces, but they are empty. What is more symbolic than buying space you don’t use? We, the ordinary, can only skulk in the shadows; my shadow is a three-bedroom flat in Camden, above a betting shop with London rats on the stairs. Children throw eggs at my back window because, my husband says, they can see the books, and the books disturb them in ways they do not understand. I look outside, beyond the eggs, and I see a place stripped of people. (I recently visited a state primary school to see if it was right for my boy. I was told that there was space for him because families were moving out; they were not rich enough to live in London.) Belgravia, a calm, pale district beloved by diplomats, is dark at night; to see a lit window is to be stunned. I walked the whole of Kensington Palace Gardens one day, looking at the rotting or renovated mansions — there is nothing in between — and I saw the Duke of Kent, hands in pockets, walking his dog. Does he see, I wondered, what I see, which is polarization and ruin?

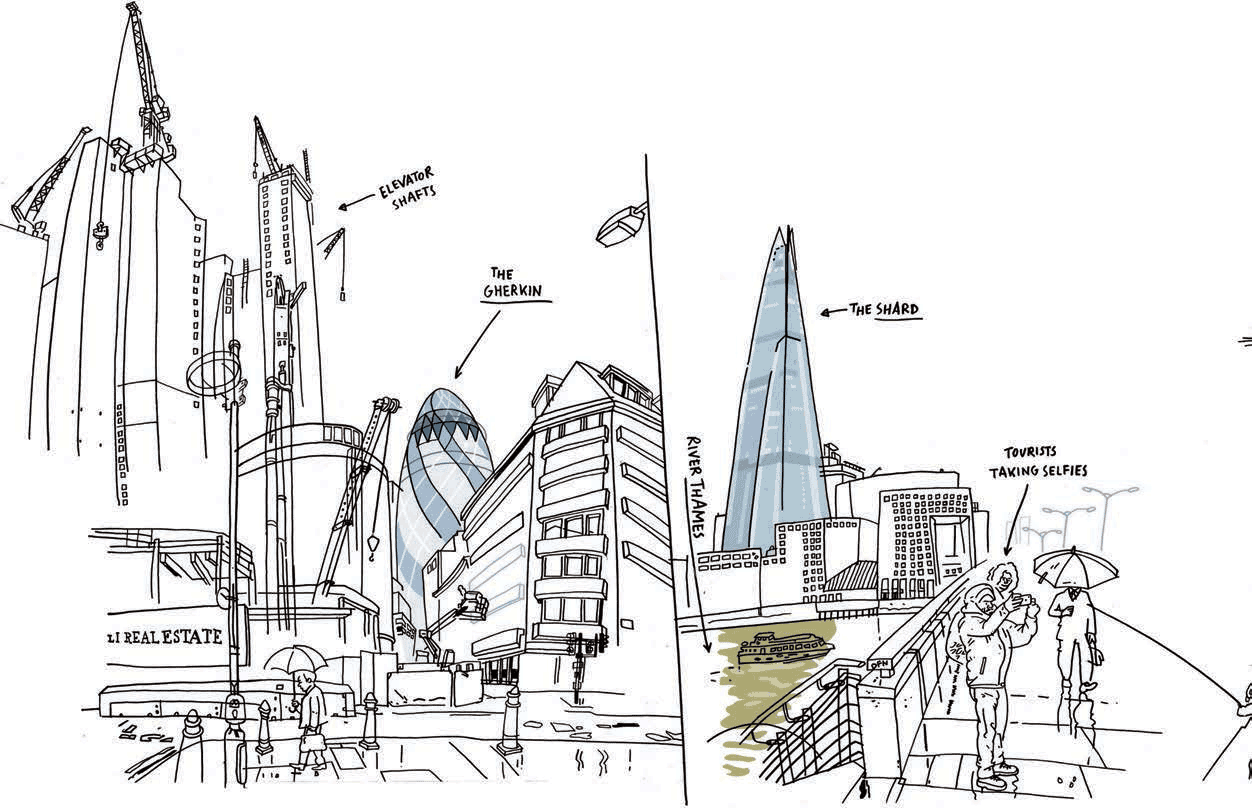

London doesn’t know where it stands now. I think Brexit was about space, although there was confusion about who, exactly, had stolen the space — the Russians, the Qataris, and the Chinese, or the Somalis, the Albanians, and the Poles? In the end, the voters blamed the latter because they are idiots. But it was all about space, and it always has been. More for us, less for them. Space for my boy but not for hers. The sky is filled with contemporary palaces that have inane names: the Shard, which is a dagger; the Gherkin, which is a penis; the Walkie-Talkie, which is an outdated communication device with public rooms decorated in homage to the Arnold Schwarzenegger space film Total Recall. It has a disgusting Sky Garden — a greenhouse in the sky — which is not a garden but a taunt: I will take the lack of something, it states, and make it art. But it is not art. It does not grieve.

I don’t know if the cranes will still with Brexit. The city has stalled under a Conservative prime minister named Theresa May, who is, for now, an absence in shoes. How the fourth estate loves to talk about her shoes, for journalists are suicide merchants now, collaborating in their irrelevance. I don’t know if the holes in the ground will sprout new buildings, remarkable only for their blandness, or just stay there gathering water, wreckage of a new and duller Blitz. No one does; those who say they do, lie.

Housing is the story in London; it is what we talk about; for politics feels remote in this age of narcissism. You need something more personal than a political movement. I grew up in a five-bedroom house; now I live with rats on the stairs, and still I know I’m lucky. To find more space, we dig down into the clay. It’s dangerous, some say, and unnatural, but haven’t people always feared to dig into the earth? Last year a pretty Georgian house near the Thames, to the west, just fell over in a metaphorical scream. One day I expect to hear that a whole terrace has gone, from Belgravia or Knightsbridge, in a moan of protest: we cannot be your metaphor! And my mind wanders further: it won’t matter, or rather it won’t be the story that everyone expects and wants to read, for the joy of schadenfreude. No plutocrat will be buried under the bricks of his hubris as he seeks to expand his space for a vintage-car collection, home cinema, or torture spa, inserted into his tomb with his Patek Philippe watch and his Maserati with its personalized license plate. Only the servants will be in.

The international rich have annexed London for its prep schools, which induce anxiety in infants for the promise of a place at Oxford in 2030. They are quite successful in creating miniature psychopathic adults. (I met one of these creatures recently, and feared him. He was eleven.) They like the tax and libel laws, which are generous, and the London Season, which is open to anyone with a silly hat, and stability, which is relative and ebbing. They also like the restaurants, which are increasingly absurd, and the shopping. The rich map of London is different from yours and mine. At the Frieze art show in Regent’s Park I saw a wooden sign marked, simply, mayfair, as if there were only two places in the city that are worthy: a tent containing a bad Picasso and a hotel with a “library suite” containing books about yacht interiors. This is a city of wealth enablers, and they practice lebensraum across Mayfair and St. James’s and Knightsbridge: whole districts fallen to idiocy. Book stylists arrange your books should the alphabet elude you; log stylists curate fireplaces; people advise on whether black toilet paper, which I once saw in a Mayfair mansion, is important. It isn’t; it’s just different from the toilet paper that other people use — it is, to borrow from the propaganda of the anti-austerity protest group Uncut, the toilet paper of the One Percent.

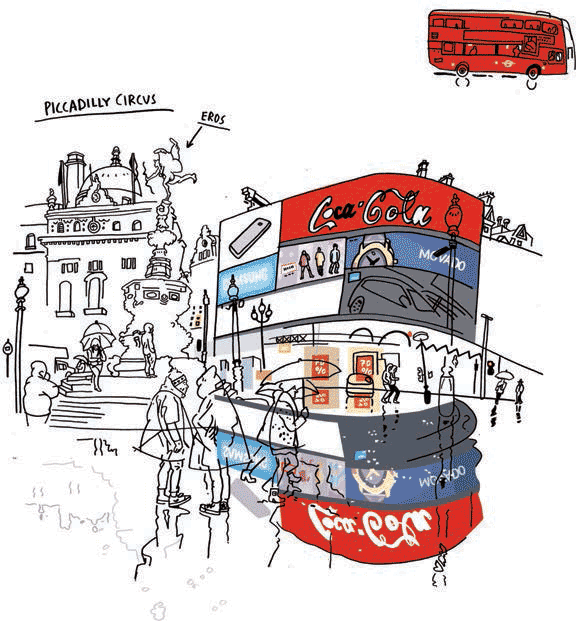

I used to love to travel under Piccadilly Circus on the Underground, feeling the throb. But the essential element — human beings — is going. Tourists do not count. They are prostrate before the city; they will take anything it gives them: an Angus Steakhouse, for instance. I want to throw myself under the legs of the tourists, screaming: Do not eat there! Like them, I no longer know London. I do not know, for instance, if the blackened mansion at 94 Piccadilly, which I always thought was Dracula’s house, for he had a house on Piccadilly, will sell for 200 million pounds, as some bit of marketing nonsense said, or remain another empty piece of space. I want to tour it, I said to a P.R. person acting for the owner. I want to look at the bones of the mansion, before it becomes a glass pylon with a disgusting kitchen. You are, he said, at the bottom of the list, but I knew that anyway. I am a writer, and I live with rats. My space is shrinking.

I used to love to travel under Piccadilly Circus on the Underground, feeling the throb. But the essential element — human beings — is going. Tourists do not count. They are prostrate before the city; they will take anything it gives them: an Angus Steakhouse, for instance. I want to throw myself under the legs of the tourists, screaming: Do not eat there! Like them, I no longer know London. I do not know, for instance, if the blackened mansion at 94 Piccadilly, which I always thought was Dracula’s house, for he had a house on Piccadilly, will sell for 200 million pounds, as some bit of marketing nonsense said, or remain another empty piece of space. I want to tour it, I said to a P.R. person acting for the owner. I want to look at the bones of the mansion, before it becomes a glass pylon with a disgusting kitchen. You are, he said, at the bottom of the list, but I knew that anyway. I am a writer, and I live with rats. My space is shrinking.

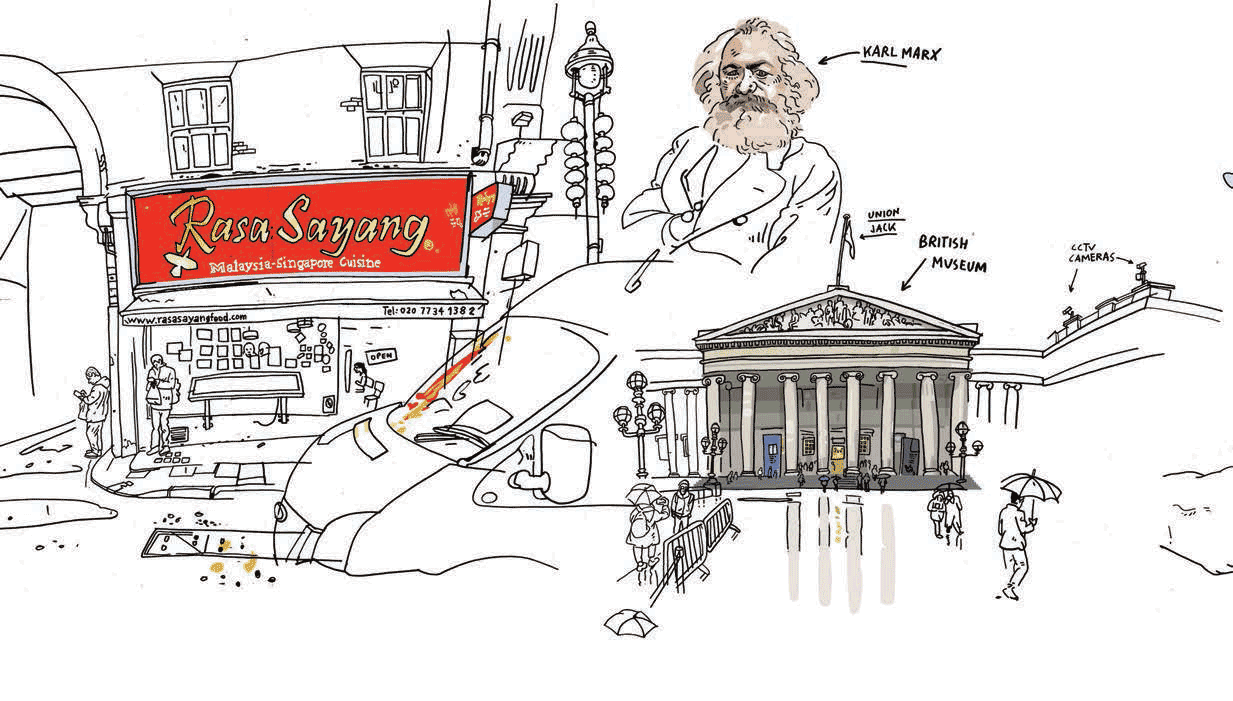

I am at the top of the list, though, for the Karl Marx Walking Tour, which meets at Piccadilly Circus on a Sunday morning. The rain is monstrous: Brexit rain, I call it, being a sentimentalist, washing London out of Europe, and no one thought to buy an ark. (London districts voted overwhelmingly to remain in the E.U. So did Gibraltar.) I can think of nothing better to do, when trying to describe the way that London has been hollowed out, than to cling to the idea of a German-Jewish ghost. It is comforting. Marx would be surprised by none of this: not the hollowing out, not the depoliticization, and not the Brexit vote.

Our guide, Mick, looks like an old-boy 1960s socialist, in cagoule, spectacles, and cap, of the kind who now rule the opposition Labour Party, as of this writing polling in the twenties but expressing, still, the hope of the insane, which exists in inverse proportion to the likely outcome. There are fifteen of us — ten tourists, three itinerant Marxists, and a friend of Mick’s — and we are wet even before we leave the awning of the Criterion Theatre, which is a late-Victorian fancy in stone. I am happy that we are doing something almost no one else would consider pleasurable or important, happy to be looking backward, because the present feels so awful, and the past — well, if Europe falls to fascism, the past will return soon enough.

We are touring Soho: London filth, arranged on ancient and irregular streets around the Berwick Street market and fabric shops. I am looking for the city I used to love. Until recently Soho belonged to the gays, the whores, the pimps, the immigrants, and the artists, who gathered in the Colony Room Club, next door to the Groucho Club, to insult one another. I got in there once, when I was twenty-seven, cold-eyed with cocaine, and stared at Damien Hirst and his pencil drawing of a skull. I thought it looked like a cabbage; myths are best left to themselves. But the Colony Room closed, sold off its art collection, and is now an expensive apartment building. It was Mr. Hyde’s London, for novelists; for tourists, it was a place in the mind. I would call it a holiday to salvageable degradation, but I grew up in a suburb of unusual tedium, even by the standards of suburbs.

Soho is now, clearly, a development opportunity, a home to private members’ clubs, and, like Hampstead, an irritating fake-Georgian village on the slopes of North London, an enormous patisserie. The day after Brexit I had breakfast at a Hampstead patisserie. Women were weeping and clutching each other. Some fretted aloud that their cleaners would be deported; they wept as their semi-beneficent racism was supplanted by something uglier.

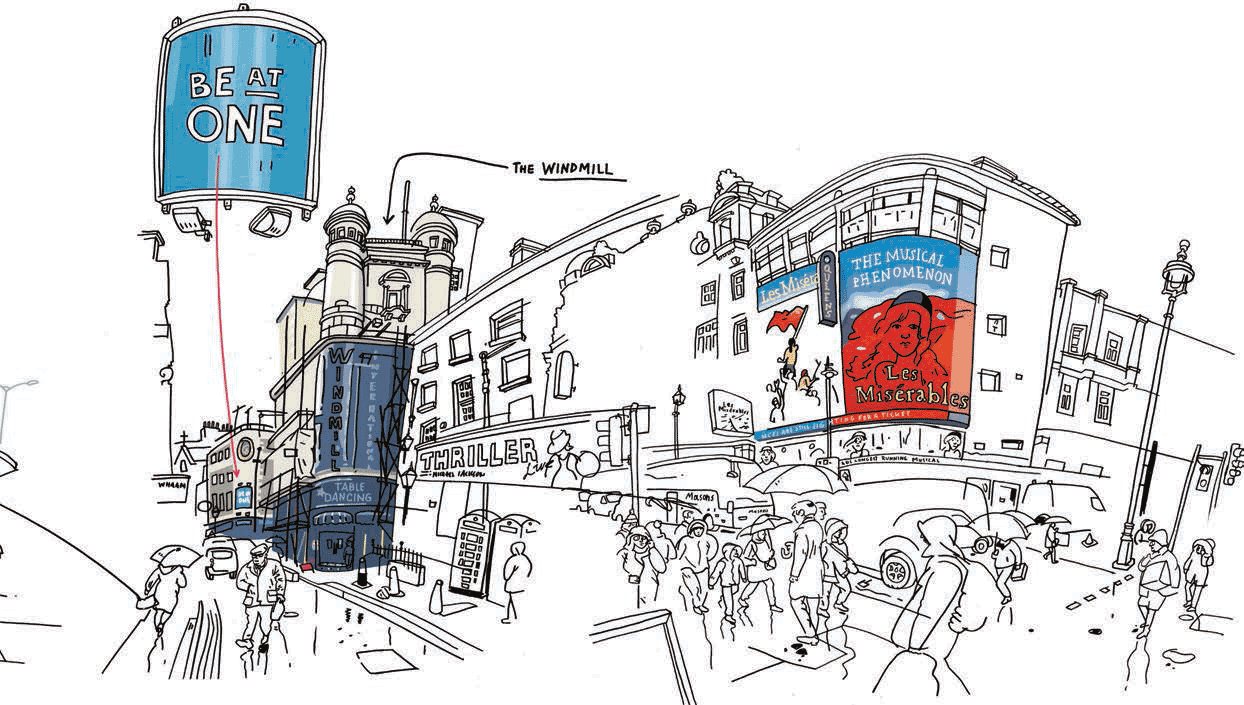

Continuing the tour, we walk to the Be At One cocktail lounge on Great Windmill Street, opposite the Windmill International: the world’s most exciting nightclub. over 100 nude international dancers. I’m not sure this signage will endure beyond Brexit, because the nude international dancers may be deported along with the cleaners, although I hope they have time to put their clothes back on. But I will not be tricked into nostalgia for the sex industry, as if it were an old-fashioned and beloved brand of candy, for a time when there was so much seditious sex in Soho that the streets gleamed with filth. I once saw an Orthodox Jew, with black hat and coat, bounce out of a Soho sex shop. That was fifteen years ago, and I’m still surprised.

Continuing the tour, we walk to the Be At One cocktail lounge on Great Windmill Street, opposite the Windmill International: the world’s most exciting nightclub. over 100 nude international dancers. I’m not sure this signage will endure beyond Brexit, because the nude international dancers may be deported along with the cleaners, although I hope they have time to put their clothes back on. But I will not be tricked into nostalgia for the sex industry, as if it were an old-fashioned and beloved brand of candy, for a time when there was so much seditious sex in Soho that the streets gleamed with filth. I once saw an Orthodox Jew, with black hat and coat, bounce out of a Soho sex shop. That was fifteen years ago, and I’m still surprised.

The Be At One cocktail lounge was once called the Red Lion. Mick thinks that is a “sensible” name for a pub, and I agree. Lions are not red in real life, it is true, but perhaps one must imagine there is something fantastical about getting shitting drunk. The Red Lion closed in 2013 (the death of the sensibly named pub arguably had the same impact on democratic engagement as the rise of Facebook, which is that it stopped people from speaking to one another), and the Be At One, which is an unpleasant quasi-tasteful blue color, was born. No one would form a political movement in the Be At One. I just cannot see it happening. It is a place for comfortable numbness, a place to forget.

Mick says that the Second Congress of the Communist League took place in the Red Lion in 1847 and that, afterward, the league asked Marx and Friedrich Engels to write the Communist Manifesto. “Unfortunately you will find that history and tradition just get trashed all the way round,” says Mick. “There’s no recognition whatsoever of the historic character of this pub if you go inside.” I can understand that; I almost respect it. Who would drink cocktails underneath a memorial to a utopia that never was?

We cross Shaftesbury Avenue, where the 1832 revolution is playing in song — it is Les Misérables, still on at the Queen’s Theatre — to Rupert Street. Here, says Mick, inside a pale, ugly building at No. 40, was a Communard club. The surviving radicals from the 1871 Paris Commune fled here, he says: “It was their home from home,” and they were tended to personally by Marx, which I find difficult to believe. I cannot imagine Karl Marx sweeping a floor near refugees. I have tried. Mick’s monologue is interrupted by a fit of coughing. Now 40 Rupert Street is — and my fingers are heavy as I type it — the Two Sportsmen restaurant and bar, and it is between the Palomar and the Thai Tho. Every part of Soho in which Marx lived and worked is now a restaurant, bistro, café, or cocktail lounge. Every single one. That is what has happened to the space; it was given over to a rice cooker. We have eaten the revolution; it is explicit.

The German Hotel, where Marx stayed with his wife for three months in 1850, is now Leicester House, a hotel, restaurant, and bar. Here, Mick says, “he didn’t pay the rent, which was a long-running part of the Karl Marx story”; the Londoners who cannot afford homes would surely understand, if only they weren’t always on Facebook, dreaming up pixelated political movements, or drinking themselves numb at the Great Windmill Street Be At One. After the 1848 revolutions, Marx spent the rest of his life in London. It wasn’t his preference, says Mick, he liked Paris, but there had been a counterrevolution to thwart his housing choices, among other things.

On Gerrard Street, in Chinatown, we pass a street party for the Queen’s ninetieth birthday, without pleasure and without comment, but we are a Marxist walking tour and obliged to be sullen in the face of bunting. My husband thinks monarchy protects us from fascism because potential Blackshirts are, instead, waving Union Jacks outside primary schools. But I seek something more solid than bunting to protect liberal democracy. Even so, there is plenty of it about, fluttering over a fraying social democracy. It keeps your eyes off the beggars. They are too numerous to describe individually; simply put, they look like they are dying. I wonder why they don’t seem angry; perhaps they’re too cold? They smile faintly at any greeting, and the city, in its way, does acknowledge them. Benches are too small to lie on; new buildings feature “anti-homeless” spikes. I think it won’t be long before they are garroted in the streets, but I am a pessimist.

At 5 Macclesfield Street, next door to what was once the headquarters of the exiled Communist League and Engels’s apartment — I imagine, happily, his solitary masculine habits, wonder if he ever swept a floor — we find Rasa Sayang’s Singapore cuisine. “That’s where Fred Engels stayed, but we don’t know what part of the building,” says Mick. “Zero respect for history,” he frets. There is no plaque, such as: on top of rasa sayang’s singapore cuisine men tried to change the course of history, but they failed.

At 5 Macclesfield Street, next door to what was once the headquarters of the exiled Communist League and Engels’s apartment — I imagine, happily, his solitary masculine habits, wonder if he ever swept a floor — we find Rasa Sayang’s Singapore cuisine. “That’s where Fred Engels stayed, but we don’t know what part of the building,” says Mick. “Zero respect for history,” he frets. There is no plaque, such as: on top of rasa sayang’s singapore cuisine men tried to change the course of history, but they failed.

Perhaps the best restaurant in which Marx once lived or worked is Quo Vadis, on Dean Street, between Sunset Strip (nude women are a kind of food) and Soho Joe’s pizza, grill, and Wagyu burgers. He had two and a half rooms on the top floor, and two of his children died here within five years. So he moved to Kentish Town.

We walk to Greek Street and see the former Establishment club, where Lenny Bruce performed on heroin and got few laughs; it was also the International Workingmen’s Association headquarters, where, Mick says, Marx fantasized that “you could bypass the capitalist class, trade directly with each other, and the capitalist class would disappear of its own accord.” This gets few laughs, too, but, to be fair, it sought none. Mick pauses, embarrassed, and says, “Nobody actually thinks that anymore,” as if we will hold him personally responsible for the nonappearance of the Revolution, as if it were a dinner guest so ill-mannered it didn’t show up or even send a note. We pass the Condé Nast College of Fashion and Design, which I prefer to call the University of Stupid. It is a pristine brick-and-steel rectangle, cold as fashion itself, managed by the magazine publishers; here, for 25,000 pounds a year, you can get work experience at Vogue. Soon, I fantasize, all surviving journalists will pass through the Condé Nast College of Fashion and Design: politics will shrink from housing to sofas to cushions to thread. We end up in the Enlightenment Room at the British Museum, by a statue of Zeus. We sing “The Internationale,” although only the Marxists — two from Brooklyn, one from Australia — know the words. The museum’s vast reading room where Marx wrote Das Kapital is now an exhibition “space” — a word I hate, it is literally an absence — above a gift shop and a toilet.

The city fights back, but I have no faith in it. The loss of each old piece of London — Kettner’s restaurant in Soho; the Chariots Roman Spa in Shoreditch, a gay bathhouse that was, curiously, described by BuzzFeed in the most sentimental terms; the Odeon West End in Leicester Square — brings a petition, a protest, a scream. It is nothing meaningful; only politics can be meaningful, and politics has shrunk and I cannot find it.

Two days after the Brexit vote, which was called a victory for “decent people” by Nigel Farage of the U.K. Independence Party — a friend to Donald Trump, like many Brexiters — I watch the “un-decent” gather for Gay Pride. There are gay soldiers, gay policemen, gay firemen, gay Jews in pink Stars of David, gay Muslims in burkas and pink sunglasses, and, at the very front of Pride — leading Pride, if you will — a bus that reads barclays. Is this pride in Barclays? If you didn’t have a wristband, the novelist Philip Hensher reported, you had to march at the back; the sponsors — Tesco, Visa, even the right-wing Telegraph — would not admit you to Gay Pride. You were not sanctioned to protest unless you were a Telegraph-reading, Visa-carrying shopper at Tesco’s. I wondered whether, if I thought very hard, I could summon Marx’s ghostly cackle from Soho. A friend told me that Barclays badges rained on the ground like evil tin confetti, but I don’t know if this is true.

There is infantilism sweeping the city, too, which is understandable if unhelpful; why not summon your childhood when there is so much to fear? The members-only club Soho House, a donkey sanctuary for the media class, has opened a branch in Shoreditch, to the east. It used to be a working-class district, pounded in the Blitz. Now it is full of men with Victorian handlebar mustaches riding penny-farthing bicycles and shops selling overpriced “rustic” vegetables with “authentic” mud. Here, in Shoreditch House, there is a line of table-tennis tables. Is that where the fourth estate was as Britain slumped out of Europe and America elected a man who looks like a crazed Rice Krispie? Playing table tennis? Nearby, the Cereal Killer Café sells a multitude of “rare” cereals in rooms designed for neglected children; when it opened, there were enormous queues as hipsters groped backward for comfort. There were protests against this too; as if protesting against branded cereal were not the most pointless political act that one could fathom. Food again.

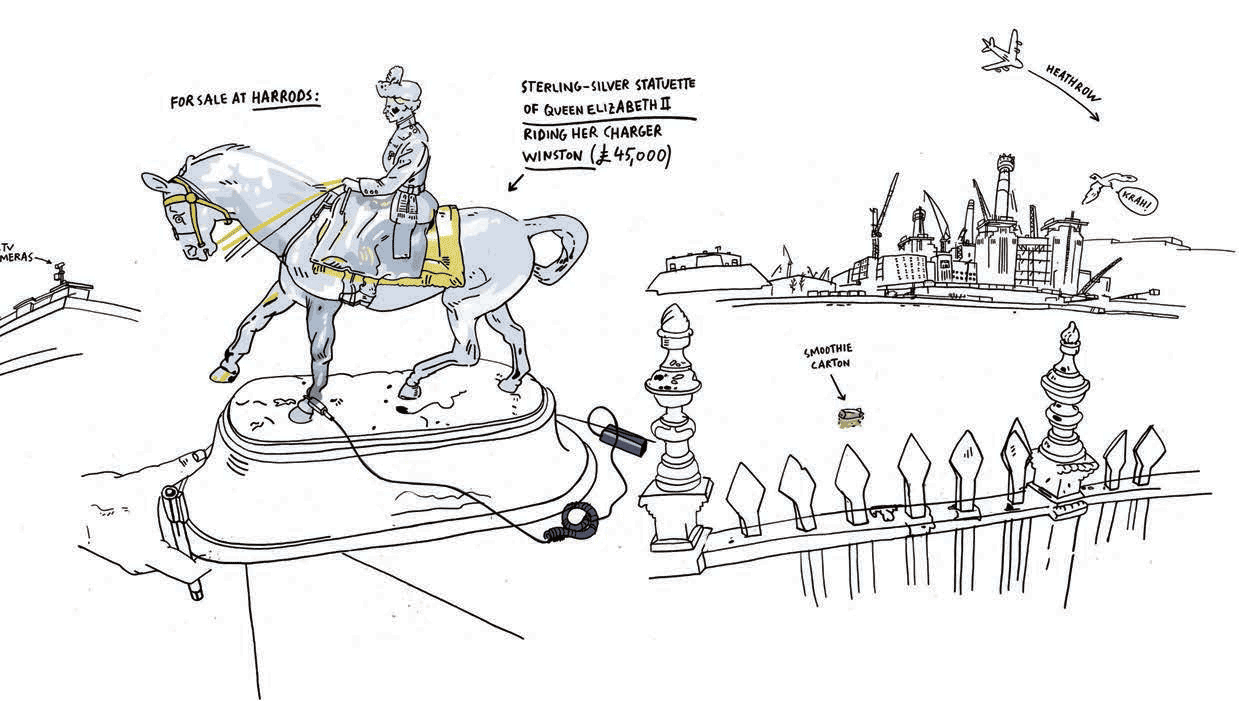

Harrods, the famous department store in Knightsbridge, is a redbrick Edwardian catastrophe with pinnacles and lights designed to be admired from far away. I am here, I suppose, looking for what killed London, because I am leaving soon. I will be gone before you read my letter. I have had enough. I can take anything but the injustice of it. Bring in the Fendi and the fake fur, I can handle that, I can laugh at it. But don’t remove the people. I have a space here for now, but I do not want it.

At least Harrods is vivid. It is an insane house; the Overlook Hotel, perhaps, but the madman covets rugs. This is where the foreign rich furnish their investment houses, for the native rich already have furniture. The still-landed aristocracy, who plan in millennia, spend almost no money at all. They are busy worrying about their cows. They have little to do with London now, for they seem to understand what has happened to it. They have sold off their Mayfair town houses and exist, for Londoners, only in the silly mirrors of Downton Abbey.

Harrods has security guards; a sign on the escalator shouts no prams! Stories about people being refused entry to Harrods — to Eden! — are still tabloid favorites, but the tabloids are confused and don’t know what side they’re on. Harrods is not really a shop; it is a boast, an entertainment. It is, I think, capitalist marketing in its purest form. It was owned by Mohamed al-Fayed, whose son, Dodi, was the last lover of Diana, Princess of Wales, and there is a gruesome monument to their sex — and her transgression — in the basement. He sold the store to the Qataris, but the sex monument lives on.

The store is decorated in fake-Egyptian style. There are papier-mâché pharaohs and female mannequins without faces staring down, because who needs a face if your ass — your dress? — looks good? Sometimes I think Harrods is the castle of a medieval lord on a feast day when the peasants have come to watch the lord eat swan: look, a swan! It feels itinerant and lifeless. Some buy; most gawp. Those who buy include Asma al-Assad, the dictator’s wife, whose orders at Harrods — she bought a 2,650-pound vase with a 15 percent discount in 2011, as her husband began his massacres — tell you something of her priorities in the world.

Inside, on floor after floor, I find goods of such surpassing ugliness I can feel only pity: for the maker, the buyer, the voyeur, the world. I cannot think of anything more pathetic than a Chanel squash racket; except, perhaps, a Chanel squash ball. You can also get a Chanel bicycle and Chanel skis. Where are the fishing rod and the automatic weapon? The Chanel umbrella, I am told by a charming woman, is particularly useful “in bad weather,” but that is how wealth enablers work. They assume stupidity in their infant customers, and the buyer, soothed, sinks to the irresponsibility of a 99,900-pound orange Kabuki Limited Edition Lead Crystal statue of a woman with a clawlike hand — and tax evasion. This covetousness, to me, is all anxiety and terror; but I have had too much psychotherapy. The customers gather on sofas with salespeople for fretting conversations as if convening with priests: this bag or that? In the Hermès concession (he was the god of trade, and that is quite witty, for high fashion) they bicker, mildly, with an imago I suspect they are barely conscious of.

Inside, on floor after floor, I find goods of such surpassing ugliness I can feel only pity: for the maker, the buyer, the voyeur, the world. I cannot think of anything more pathetic than a Chanel squash racket; except, perhaps, a Chanel squash ball. You can also get a Chanel bicycle and Chanel skis. Where are the fishing rod and the automatic weapon? The Chanel umbrella, I am told by a charming woman, is particularly useful “in bad weather,” but that is how wealth enablers work. They assume stupidity in their infant customers, and the buyer, soothed, sinks to the irresponsibility of a 99,900-pound orange Kabuki Limited Edition Lead Crystal statue of a woman with a clawlike hand — and tax evasion. This covetousness, to me, is all anxiety and terror; but I have had too much psychotherapy. The customers gather on sofas with salespeople for fretting conversations as if convening with priests: this bag or that? In the Hermès concession (he was the god of trade, and that is quite witty, for high fashion) they bicker, mildly, with an imago I suspect they are barely conscious of.

I go into high fashion. Here you can decorate yourself in any way, if you are so bewitched: a ghost, a lizard, a child. And here I have the experience I always have in places that sell high fashion. It is as though they plan it. In Alexander McQueen — he killed himself, but his logo survived — the salesman looks at me, and says, simply and without malice: Are you lost?

I am most fascinated by the children’s clothing department, specifically Baby Dior. Adult Dior is really for pretty children; to see these clothes miniaturized is mesmerizing. They hang on racks, as if for gilded dwarfs or fairy children, in orange, pink, and yellow. There is something obscene about a child in Dior; too knowing, almost pornographic.

Then I find the Millionaire Gallery. I have reviewed the Disney Café and investigated the Bibbidi Bobbidi Boutique, where, for 1,000 pounds, a female child can be transformed into a glittering Disney hag — and I did not think Harrods had anything left to disgust me. But here is an autograph of King Fahd of Saudi Arabia, mounted with a photograph. I don’t think Alexander McQueen could have done anything with him, for Fahd is truly a man in search of a Chanel burka. It is 5,995 pounds, and already sold. I name the genre Wahhabi Collectibles. “We had King Faisal,” says the salesman. “You can’t get Abdullah anymore.”

There is a collection of autographs of every British monarch since George I, as if you needed evidence that they could actually write their names (£136,795). Forty-four presidents of the United States in a monstrous triptych (£230,695). Astronauts; James Bond; Ronald Reagan; Mikhail Gorbachev with a chunk of the Berlin wall; footballers; Marlon Brando as the Godfather; a note from Princess Diana (a woman, yes, but she died in a tragedy); superheroes, inevitably, for they are the new philosophers. I have a theory that Donald Trump would not have won the election without the superhero-genre film, which prepared America for the savior who is also a fucking idiot, but I fear I couldn’t do it justice. He will be here soon. This is all his style, or lack of it. How he would love the emptiness of Harrods! It is his London, not mine. Why don’t they just frame a billion-dollar bill and end it? Or mount Total War in gilt? All of this is available in London; all of this is for sale. The greatest wave of wealth to wash through the city in a hundred years and this is what they left us. A photograph of King Fahd and a diamanté picture of an owl.