Discussed in this essay:

Do I Make Myself Clear? Why Writing Well Matters, by Harold Evans. Little, Brown. 416 pages. $27.

Writing Without Bullshit: Boost Your Career by Saying What You Mean, by Josh Bernoff. Harper Business. 304 pages. $23.99.

How to Write Like Tolstoy: A Journey into the Minds of Our Greatest Writers, by Richard Cohen. Random House. 352 pages. $28.

Why Write? A Master Class on the Art of Writing and Why It Matters, by Mark Edmundson. Bloomsbury. 288 pages. $26.

Soul at the White Heat: Inspiration, Obsession, and the Writing Life, by Joyce Carol Oates. Ecco. 400 pages. $27.99.

How Fiction Works, by James Wood. Picador. 288 pages. $17.

I’ve run the numbers, and can confirm that the U.S. Constitution is 77 percent bullshit. Witness the famous preamble: “We the People of the United States.” Not bad. Could be shorter. What’s wrong with “We Americans”? “In Order to form a more perfect Union.” Eight words in and already we’re breeches-deep in b.s. “In order to” is what I like to call a flesh eater — a phrase that eats up space and reduces the impact of your writing. “To” would be better. As for “more perfect” — what were you thinking, guys? The Union is either perfect or it isn’t.

establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Hard to know where to start here. I’ve italicized unnecessary words (“the general,” “the Blessings of”), misspellings (“Tranquility”), incorrect capitalizations (“Justice,” “Welfare”), tautologies (“do ordain and establish”), statements of the obvious (“for the United States of America”), non-standard usages (“secure . . . to”), and general old-style windiness (“provide for the common defence” instead of “defend ourselves”). There are fifty-two words in the preamble. I’ve marked forty as either incorrect, misplaced, or vague, leaving only twelve that are apt and impactful. Assuming the style of the preamble to be representative of the whole, the meaning ratio of the U.S. Constitution is a fraction over 23 percent.

That’s simply not acceptable.

For Josh Bernoff, the author of Writing Without Bullshit, meaning is quantifiable. (My analysis of the Constitution is founded on Bernoffian techniques.) Bernoff’s style is direct verging on despotic: the intended effect seems to be a state of mild arousal on the reader’s part at the author’s unyielding scorn for verbal flatus. As rookie bullshit detectors we are invited, if not required, to subscribe to an all-encompassing Iron Imperative: “Treat the reader’s time as more valuable than your own” (Bernoff’s italics).

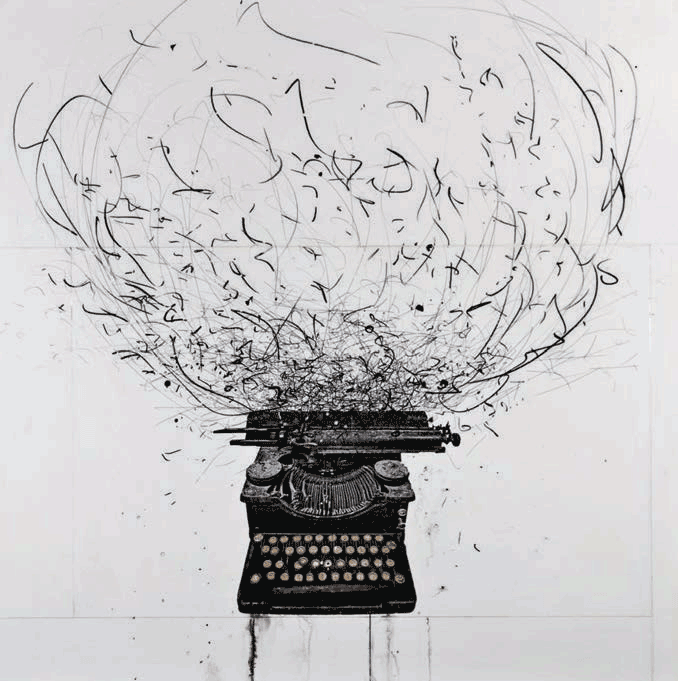

Eastern Story, mixed media on panel by Andre Petterson. Courtesy the

artist and Bau-Xi Gallery, Toronto and Vancouver, British Columbia

Writing Without Bullshit arrives amid a glut of recent guides to stylistic hygiene, and although Bernoff is careful to restrict his remit to business communications (“My advice will not get you published in The New Yorker”), his book shares with its more literary counterparts a belief that bad writing is a function of evasiveness, of a reluctance to engage with the plain truths conveyed by plain language. It also shares a trait that may be endemic to the genre: a failure to practice what it preaches.

“The tide of bullshit is rising.” It’s hard to argue with Bernoff’s premise, that a discourse already hospitable to verbiage — “Business English” — has been rendered exponentially more so by technology. “Any idiot,” he writes, “can type and distribute content to dozens or even thousands of people, and many do, whether through email or a blog.” Editorial intervention is a relic of the pre–Information Age. Unsupervised marketing interns bloat our social-media timelines with drivel. Bernoff is a Canute in an ocean of ordure. As such the gist of his advice is unimpeachable. Get to the point. Avoid passive constructions. Eliminate jargon, qualifiers, and weasel words like “probably” and “millions.” Identify your audience and don’t be shy about addressing them in the second person. Bernoff takes a prattling job ad for Johnson and Johnson — “The successful candidate will be the key leader and customer advocate working closely with the Strategic Account and Sales Leaders across J&J” — and rewrites it thus: “You’ll work with sales to coordinate our resources.” Bullshit bagged and binned.

Where Bernoff begins to undermine his case is in precisely the pithiness his b.s. aversion tends to promote. Indirection has its benefits, one being a reduced likelihood of weirdly self-congratulatory assertions of basic humanity. “As a parent,” Bernoff tells us, “I hate child pornography as much as anyone.” Really? Me, too. (Same goes for those Nazis: I just don’t like them.) The sentence appears in a chapter on the misuse of statistics, drawing on data quoted by a child-protection organization as an example; Bernoff may feel the sensitivity of the material demands some form of authorial disavowal, but in confronting this so directly he merely increases the queasiness. Besides, the sentence is scuppered by a prefatory (and thus, by Bernoff’s lights, redundant) modifier that is subtly contradicted by the closing comparative phrase.

Elsewhere, Bernoff’s straight-shooting style is indistinguishable from the business b.s. it purports to hold at arm’s length: “You leverage the urgency to complete the interviews that you need”; “I include a slogan to help you dig in productively.” The “right tone” for emails is “business casual,” a term that in all its horrors might well apply to Bernoff’s style in toto, embracing as it does a sort of tech-sector breeziness (“cool stuff that came to you as you were writing”), novelty-necktie claims to idiosyncrasy (“It is in my nature to look for a strange, warped way to put a spin on anything people say, write, or do”), and single-sentence paragraphs denoting the author’s turkey-talking clarity of mind (“Prose sucks”). There is also the occasional wince-inducing attack of the cutes: “Good copy editors save you from your flaws. Reward them (preferably with chocolate).” The effect recalls no one so strongly as Michael Scott, the delusional middle manager from The Office. Tip by tip, acronym by iron imperative, it’s hard not to detect a whiff of one sort of bullshit being replaced by another.

Style guides exist to herd the cats of written language. The classic of the genre, William Strunk Jr. and E. B. White’s Elements of Style, is bracingly prescriptive. The first edition, privately printed in 1918 by Strunk, an English professor at Cornell, was concerned with narrow matters of usage and composition: set off nonrestrictive clauses with commas, make sure participial phrases refer to the grammatical subject, “omit needless words.” In 1959, White, a former student of Strunk’s, erstwhile Harper’s columnist, and the author of Charlotte’s Web, revised the guide, appending a new section, “An Approach to Style,” which was no less high-handed for being, by White’s own admission, built on more subjective ground than Strunk’s chapters. “Avoid fancy words.” “Do not overstate.” “Rich, ornate prose is hard to digest, generally unwholesome, and sometimes nauseating.” The righteous tone is unmistakable; while a modern reader might infer in his precepts an invitation to learn the rules so that they might be broken more advisedly — to learn to draw like Raphael before you start spattering the canvas with house paint — White’s own style is so brusque as to amount to a wooden ruler held over the reader’s knuckles. It is an affirmation, albeit unspoken, of plainness as less an aesthetic choice than an American creed. (What fraudulence can be smuggled under cover of “plainness” is a matter we will return to.)

Contemporary style guides tend to be less categorical, even if an echo of White’s moralism is discernible in Bernoff’s scatologically inflected disgust at fancy prose, or in the little geysers of indignation that erupt in Why Write? A Master Class on the Art of Writing and Why It Matters by Mark Edmundson, a professor of English at the University of Virginia. (Reading Stephen King is a “rank waste of time”; the “undersong” of Saul Bellow’s Herzog, “a protracted masculine whine.”) Many proceed by example rather than edict, with the result that they fall somewhere between instruction manuals and exercises in practical criticism.

A case in point is Harold Evans’s Do I Make Myself Clear? Evans was the editor of the London Sunday Times in the late Sixties and Seventies, overseeing the team that exposed Kim Philby as a Soviet spy and campaigned to secure compensation for the victims of the anti-nausea drug thalidomide. In 1973, he wrote Newsman’s English, a style guide aimed at journalists; in 2000, an updated edition was published as Essential English for Journalists and Writers. To an extent, Do I Make Myself Clear? represents more of the same. In an early chapter, “The Sentence Clinic,” Evans excerpts prose from a variety of sources — federal regulations, legal documents, articles from the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times — and subjects them to the unforgiving editorial eye that he acquired on Fleet Street. Sentences starting with “overweening” subordinate clauses — Evans calls them “predatory clauses” — are reorganized so that the subject and main verb come first. Solitary modifiers, beached at the end of a sentence by lengthy parentheses, are reunited with their modificands.

Not even Jane Austen is spared the blue pencil. Evans is so bold as to split an “overloaded” thought from Pride and Prejudice into “four varied sentences” without “losing the flavor”:

The vague and unsettled suspicions which uncertainty had produced of what Mr. Darcy might have been doing to forward her sister’s match which she had feared to encourage, as an exertion of goodness too great to be probable, and at the same time dreaded to be just, from the pain of obligation, were proved beyond their greatest extent to be true!

becomes

She had been filled by vague and unsettled suspicions about what Mr. Darcy might have been doing to forward her sister’s match. She had not liked to dwell on these. Such an exertion of goodness seemed improbable, yet she had dreaded the idea that the suspicions might be just, for she would then be under obligation to him. Now the suspicions were proved beyond their greatest extent to be true.

Nine words longer, but — in Evans’s unblushing view — it makes its point “more clearly and economically.” He is at his most persuasive, or at least defensible, in these practical examples, enacting elementary principles of sentence construction that readers might easily apply to their own imperfect efforts. He is less so in the observance of his own rules. Like Bernoff and White, Evans advocates plainness of address, yet his prose is riddled with grandiloquent Latinisms and mock-heroic contortions: “the overlooked malefactions of the predatory clause,” “may you be as braced for execrations about deviant tendencies in the deployment of who and whom, and which and that, as Churchill was for the impertinences of the vocative case.”

Evans warns against elegant variation, but tells us that “when you write in the passive voice you can’t escape adding fat any more than you can escape piling on adipose tissue when you grab a doughnut.” He provides a list of 199 clichés to be avoided, but is capable of writing a sentence like “I pounded the typewriter to make sure the brilliant but complex work of the investigative team known as Insight . . . could be understood by the man on the Clapham bus as clearly as the lawyers who would be at our throat before the ink was dry,” which by my count contains four.

Occasionally the prose reads as if it had been translated from the Chinese by the guy who normally does the instructions for cheap calculators: “Hey, these nouns and verbs aren’t bits of silicon you can dope with chemicals (boron, phosphorous and arsenic), drop into a kiln at 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and slice and dice.” Commas are frequently used to join independent clauses — “I appreciate engineers, I wrote a book about their achievements.” The term “dangling modifier” is used incorrectly, to describe a phrase that is detached from the main verb by a parenthetical insertion but refers unambiguously to its intended subject. For fear that they be allowed to speak for themselves, Evans talks over his metaphors like an overbearing husband at a dinner party: “It puts you, the word mechanic, in the position of the auto mechanic who makes sense of the connections under the hood.”

To Evans’s credit, he admits, at least in passing, to flaws he identifies in others — needless slips into the passive voice, for instance, or the overuse of vague quantifiers like “some” and “often.” For such a stern critic of “obscurity, ugliness, and verbosity,” however, Evans is far too easy on himself. Determined readers may begin to wonder if some unalterable law obtains, whereby the very act of writing a style guide either blinds the author to deficiencies in her own style or, conceivably, causes those deficiencies in the first place. Take this, from Why Write?:

No matter how good what we write today might be, it will almost surely sink into “the dark backward and abysm of time,” to quote Shakespeare — that writer whose works almost surely never will so long as humans (or technologically enhanced or atomically mutated beings that resemble them) traverse the crust of the planet.

Shakespeare? Atomically mutated beings? Traversing the crust? The clash of registers is so jarring as to recall George Saunders at his most deliriously satirical. Still, it does provide a workable answer to the question Edmundson poses in his title: to get one’s thoughts in order. I make this criticism safe in the knowledge that its object can dismiss it out of hand. As a reviewer, I am, according to Edmundson, “enraged at having been left out in the disposition of true gifts and wish to puncture every man or woman who has been endowed.” My “gripe” is therefore with my “own talent or lack thereof.”

Maybe so, but a tendency to unsupported and, in many cases, ill-tempered assertion is another characteristic Why Write? has in common with its peers. Edmundson, as noted, dislikes book reviewers, Stephen King, and Moses Herzog; in How to Write Like Tolstoy, Richard Cohen is likewise content to light the touch paper of criticism before running for cover. In one chapter he quotes at length from a review in which James Wood praises James Kelman’s nuanced deployment of the word “fuck” and its cognates. Wood’s point duly relayed, Cohen then has a pop at both critic and novelist. Wood’s defense of Kelman, he says, is “like praising a musician for how many sounds he can get out of a single instrument; the result is impressive but quickly palls.” Martin Amis is “often at his best as a literary critic.” D. H. Lawrence is “didactic . . . but his writing can take one’s breath away.” This isn’t criticism: it’s a Twitter feed. And would it “pall” to hear Murray Perahia extract the maximum number of sounds from a “single” Steinway? Cohen’s analogy simply doesn’t work.

The peremptoriness of Edmundson and Cohen’s judgments is symptomatic of the genre’s fatal ill-definition. What are these books for? In attempting to straddle the how-to guide and the critical study, they instead fall into the chasm between them, neither offering much in the way of practicable advice nor subjecting the writers they cite to worthwhile textual analysis.

In Tom Stoppard’s play The Real Thing, the main character, Henry, a playwright, likens good writing to a cricket bat. A well-made bat is so sprung that, hit right, a “cricket ball will travel two hundred yards in four seconds, and all you’ve done is give it a knock like knocking the top off a bottle of stout, and it makes a noise like a trout taking a fly.” To Henry, a script by a rival writer is a lump of wood masquerading as a cricket bat. “If you hit a ball with it,” he says, “the ball will travel about ten feet and you will drop the bat and dance about shouting ‘Ouch!’ with your hands stuck into your armpits.”

Literary style is the difference between a cricket bat and a lump of wood. It is the unapologetic authorial sensibility — “an absolute way of seeing things,” in Flaubert’s phrase — rendered in language that matches it as precisely as language ever can. When that sensibility is fine, humane, and receptive, and its owner’s ear sufficiently attuned not to deaden or distort it too greatly — when the pieces of the cricket bat are “cunningly put together in a certain way so that the whole thing is sprung, like a dance floor” — the conditions for good writing will be in place, “so that,” as Henry puts it, “when we throw up an idea and give it a little knock, it might . . . travel.”

These are big whens. To accept my definition of style is to concede that for it to assert itself, a number of pretty unusual characteristics have to coexist in one individual. As such, a gifted writer’s style is as irreducible and arbitrarily conferred as any talent; amenable to practice and refinement, sure, but at base as God-given and inimitable as Federer’s touch or Picasso’s hand. Here lies the existential challenge faced by the style guide or writer’s manual: beyond the nuts and bolts of usage and basic writerly manners, they are attempting to teach the unteachable.

Which — naturally — is not to say that the elements of a writer’s style can’t be parsed to good purpose. Evans name-checks Lewis Lapham, editor emeritus of this magazine, who, like Borges’s Pierre Menard, finds “joy and inspiration in writing out [other writers’] passages,” although more “for the pleasure of the rhythms” than as an act of appropriation. (“Lewis Lapham, Author of the Quixote.”) Even if literary style precludes its own replicability, there is surely some use — some deeper clue as to what to listen for in our own faltering efforts — in Lapham’s close attention to the rhythms of prose he admires, or in turning to the forensic aesthetics of the best literary criticism.

In The Nearest Thing to Life, his memoir-cum-critical-treatise, James Wood writes that “literary criticism is unique because one has the great privilege of performing it in the same medium one is describing.” It’s a measure of the preferability of his approach — its greater utility to students of style — that his prose bears comparison with the objects of its scrutiny. Here he is (in How Fiction Works) on a passage from D. H. Lawrence’s Sea and Sardinia, describing the author’s early-morning departure from a house he has loved:

Its complexity, such as it is, lies in his attempt to use his prose to register, minute by minute, the painful largo of this farewell. Each sentence slows down to make its own farewell: “Scent of mimosa, and then of jasmine. The lovely mimosa tree invisible.” First you smell the scent, then you see — or apprehend — the tree. After that, the path. Sentence by sentence.

Just as Lawrence subjects his prose to its own “painful largo,” so does Wood — “After that, the path. Sentence by sentence” — and thus the style of the appraisal redescribes the original. Wood is “speaking to literature in its own language”; the reader is enlightened twice over.

In Soul at the White Heat, her new collection of essays and criticism, Joyce Carol Oates is engaged in something comparable. The title is taken from Emily Dickinson’s “Dare you see a Soul at the White Heat?” That poem challenges the reader to withstand what the poet must, the white heat of her merciless introspection. Dickinson crops up again in the essay “This I Believe: Five Motives for Writing” as a standard-bearer for obliquity: “Tell all the truth but tell it slant — / Success in Circuit lies.” In Oates’s view, the task for most writers is to “illuminate” the unfamiliar without adopting a reductive moral or political position. Without preaching, in other words. As a fairly loose assembly of old journalism, Soul at the White Heat neither amounts to a unified theory of literary practice nor affects to; nonetheless, what emerges most forcefully from Oates’s writing on writing is an alertness to the principle of indirection laid out in Dickinson’s lines. Oates locates the humor and pathos of Lorrie Moore’s short story “How to Become a Writer” in the “interstices of [the narrator’s] comical self-absorption.” It’s the beautifully modulated “myopia” of the narrative point of view that allows the reader to see beyond it. Indirection, telling it slant: they could stand as a riposte to the prescriptive simplicities of the writing manual. Success in circuit lies.

In his chapter on word choice, Harold Evans rightly takes issue with the misuse of the term “credit” in news media. In 2014, Boko Haram was “credited” with the kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls in Chibok, Nigeria. A year later, on the night of the terror attacks in Paris, a TV commentator reported that no one had yet “claimed credit.” This is to ventriloquize the terrorists: to claim credit for an act is to imply its righteousness. Evans proposes a clearer-sighted alternative: “Nobody has yet admitted . . . responsibility.”

Media style editors have their work cut out for them in the era of global Trumpism. In what abruptly seems, by comparison, a lost utopia of global stability and responsible leadership, news organizations were reprimanded for lending excessive credence to the enemies of Western democracy. In June 2015, David Cameron, restored with an unexpectedly solid mandate to the prime ministership of the United Kingdom, called on the BBC to stop using the term “Islamic State,” arguing that such language helped reify the group’s ambitions to establish a caliphate. (The BBC objected that it often referred to the group as the “so-called Islamic State.”) Now, when the external threat is matched, if not dwarfed, by the threat from within, the task falls to our own social and political structures: to resist the discursive sleight of hand that would normalize the abhorrent or seek in the name of self-tranquilization to foresee four or more years of Donald Trump as anything other than a catastrophe.

The auguries are poor. Three weeks after the election, the Guardian ran an article defending its use of the term “alt-right” on the grounds that it reflected “the breadth of the movement” — as if “far” or “extreme right” wouldn’t, or the efforts of the fascists to rebrand themselves in less openly provocative terms weren’t an act of cynical misinformation the media had an absolute duty to call out. The New York Times went a step further, describing Steve Bannon, Trump’s white-supremacist choice for chief strategist, as nothing more toxic or dismaying than a “conservative provocateur.” The argument that Bannon’s ethnonationalist agitprop is well met by such an urbane, unruffled response loses ground in proportion to his proximity to power; downplaying the dangers of his appointment narrows the gap between levelheadedness and appeasement.

Trump and his ilk effect an odd reversal of Dickinson: they tell all the lies but tell them straight. When a campaign founded on open and continuous falsehood can include among those falsehoods the claim that it is speaking the unillusioned, plain language of the ordinary voter; when the president-elect promises to “drain the swamp,” then fills his Cabinet with corporate insiders; when a candidate can aim to make a country great by showing such contempt for the constitution that made it so; when these conditions apply, reattaching words to their meanings takes on the status of survival instinct.

“Look after” words, Henry tells his lover in The Real Thing, and “you can build bridges across incomprehension and chaos.” Bridges were burned on November 8, 2016. It may take more than keeping an eye on prefatory subordinate clauses to help rebuild them. If an outgoing president of such rare articulacy can fail to persuade the electorate, at least in sufficient numbers, of the dangers in appointing a shameless liar to succeed him, it can only make the scale of the task — defying the new administration’s bullshit — all the more alarmingly clear. In chapter 4 of his book, subtitled “Ten Shortcuts to Making Yourself Clear” — and written, I should add, before the outcome of the election was known — Harold Evans praises Obama for pitting “his eloquence against the anti-Muslim demagoguery of Donald Trump” during a visit to a mosque in Baltimore.

Look how he did it in a single phrase, the moral thought fused by a gentle alliteration: “None of us can be silent. We can’t be bystanders to bigotry.”

The three words were headlines around the world. Three words more powerful than a thousand rants.

Much good they did us.