Discussed in this essay:

From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds, by Daniel C. Dennett. W. W. Norton. 496 pages. $28.95.

Consciousness Explained, by Daniel C. Dennett. Back Bay Books. 528 pages. $18.

The great dream of the modern scientific age is a total synthesis of human knowledge. The behavior of living organisms — including such complex human behavior as political organization and culture making — will be explained in biological terms, biology explained in chemical terms, chemistry explained in physical terms, and physics, finally, explained in terms of a handful of immutable laws governing matter. The baroque structures into which this matter is capable of configuring itself might require us to adopt a chemical or a biological or even an anthropological stance at different moments, but these interpretative frameworks do not introduce new evidence into the picture. A biologist can’t rely on some mysterious élan vital to do explanatory work, just as an anthropologist can’t account for a tribal burial rite by asserting the existence of ancestral spirits. The physical facts are all the facts.

This project has been remarkably successful, particularly in the century and a half since Charles Darwin bequeathed us the concept of evolution through random variation and natural selection, which began as a biological theory but has since been applied to every field of human knowledge. Only one category of facts has so far resisted assimilation into this scheme: mental facts. The trouble can be framed in many ways, but it ultimately comes down to the difficulty of explaining subjective experience in objective, material terms.

That human consciousness might not be subject to the same laws that govern the physical order was for a long time considered a feature of the grand synthesis rather than a bug. The whole undertaking was kicked off by René Descartes’s strict separation of the thinking thing — the res cogitans — from the body that contained it: the soul belonged to an immaterial realm of mental substance, the body to the brute mechanical world. The latter could be studied empirically, the former only through introspection. Descartes was notoriously vague on how mental and physical substances might interact, but whatever its metaphysical justification, Cartesian dualism had its uses, especially during an era in which encroaching on the religious domain could be dangerous for scientists. Even today, it survives in concepts such as Stephen Jay Gould’s “non-overlapping magisteria,” the idea that science and religion concern themselves with essentially different questions and thus don’t have to be reconciled. The scientific worldview, however, is epistemically greedy. It wants to provide a comprehensive picture of reality, and no picture that leaves out something as fundamental as human experience itself is complete enough to be really satisfying.

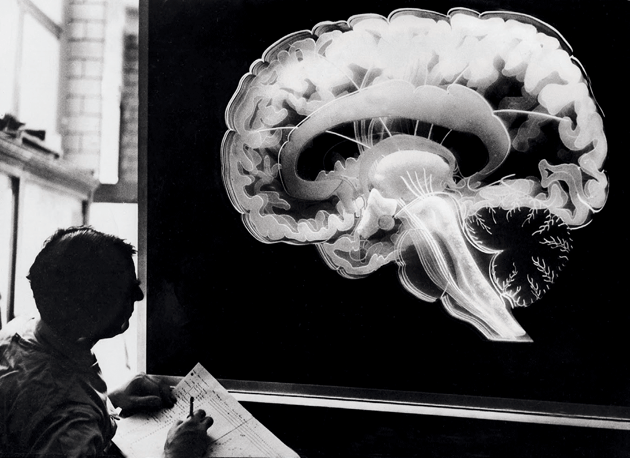

If the sciences had made no headway since Descartes in the effort to understand human consciousness, it might be possible to preserve his distinction, but neurologists, psychologists, and cognitive scientists have learned more than enough to convince them that the mind is the physical brain, or at least a function of it, and that no additional mental substance or thinking thing exists. We know which parts of the brain perform basic life functions, which parts control speech, spatiotemporal coordination, and higher-order reasoning. We know how the brain communicates with the rest of the nervous system. We know a good deal about how the brain converts sense data into perceptions, stores those perceptions as memories, and retrieves those memories at a later date. Any gaps in our understanding are chalked up to the complexity of the brain and the relative youth of cognitive science as a discipline.

Yet there still seems to be something left unaccounted for. When I see a stop sign, light reflects off the sign and passes through the lens of my eye into the retina, where rods and cones convert the information carried in that light into electrical impulses that are sent to my brain. My brain recognizes the significance of these impulses and responds by sending various signals throughout my body, coordinating my efforts to bring my car to a safe stop. But there is something else happening, too, which is the qualitative sensation of seeing redness.

Our functionalist understanding of cognition has no explanation for such sensations, which philosophers refer to as “qualia.” The electrical impulses sent from eye to brain and recognized as a red stop sign could as easily be converted into binary code and fed to a computer, and that computer could be programmed to recognize the import of the signal — but that computer would not see something red in the way that I do. And this fact raises another issue: if the functional work of cognition can be done without qualia, what is consciousness for? What possible evolutionary basis could there be for something that doesn’t even participate in the chain of physical causality?

The philosopher David Chalmers distinguishes between “psychological” and “phenomenal” concepts of the mind. In his view, the connection between the first of these and brain functioning presents various “easy” problems that a materialist study of cognition can solve: “How does the brain process environmental stimulation? How does it integrate information? How do we produce reports on internal states?” But answering these questions does not answer the “hard” question posed by the phenomenal mind: “Why is all this processing accompanied by an experienced inner life?”

Most of those who consider the question agree that the hard problem exists, but there is wide disagreement about how deep it runs, how close we are to solving it, and even whether a solution is theoretically possible. Writing not long ago in these pages, the biologist Edward O. Wilson said that “no scientific quest is more important to humanity” than the effort to understand consciousness, but seemed at the same time to recognize, even celebrate, the impossibility of a comprehensive account of subjective experience:

Because the individual mind cannot be fully described by itself or by any separate researcher, the self — celebrated star player in the scenarios of consciousness — can go on passionately believing in its independence and free will.

Steven Pinker calls Chalmers’s easy problem “access” and his hard problem “sentience” and reports that “as far as scientific explanation goes,” sentience “might as well not exist.” Finally, he claims, “the mystery remains a mystery, a topic not for science but . . . for late-night dorm room bull sessions.” It’s rather disappointing to see one of the world’s foremost cognitive scientists hand off such a fundamental question to stoned undergrads, but Pinker reassures us that “our incomprehension of sentience does not impede our understanding of how the mind works in the least.”

Others are less sanguine. The philosopher Thomas Nagel has argued that “a true appreciation of the difficulty of the problem must eventually change our conception of the place of the physical sciences in describing the natural order.” He has defined consciousness evocatively as the condition of there being something it is like to be an organism. Humans and bats and trees, for example, are all living organisms, but that doesn’t mean there is something that it is like to be all of them. We have intimate knowledge of what it is like to be a human, and intuition tells us that there is nothing that it is like to be a tree. But what is it like to be a bat?

It will not help to try to imagine that one has webbing on one’s arms, which enables one to fly around at dusk and dawn catching insects in one’s mouth; that one has very poor vision, and perceives the surrounding world by a system of reflected high-frequency sound signals; and that one spends the day hanging upside down by one’s feet in an attic. In so far as I can imagine this (which is not very far), it tells me only what it would be like for me to behave as a bat behaves. But that is not the question. I want to know what it is like for a bat to be a bat. Yet if I try to imagine this, I am restricted to the resources of my own mind, and those resources are inadequate to the task.

Analogy from personal experience gives us greater clarity to imagine what it is like to be a human other than ourselves, but nonetheless the problem persists. We can never have direct access to any consciousness except our own, which would seem to make a material account of the phenomenon impossible. “For if the facts of experience — facts about what it is like for the experiencing organism — are accessible only from one point of view,” Nagel writes, “then it is a mystery how the true character of experiences could be revealed in the physical operation of that organism.”

Given our inability to physically account for consciousness, it is tempting to jettison the phenomenal mind like so many other bits of pre-modern superstition. But we know the qualitative sensation of being conscious too intimately for that. In a certain sense, it is the only thing we know. When we talk in vague terms about qualia or subjective experience, the thing we are trying to describe is precisely that part of cognition that is always present to us but never available to outside observation. The mystery seems destined to remain a mystery.

Or maybe not. Now in his mid-seventies, Daniel Dennett has dedicated much of the past five decades to dismantling the familiar narrative laid out above. In his view, the real hard problem of consciousness is the pernicious notion that there is anything left to be considered once the easy problems have been solved. Dennett attributes the endurance of this notion to wishful thinking on the part of people who want to preserve some bit of human specialness that can’t be fit into the materialist scheme. Such people have been helped along by ontologically confused notions like qualia and by “intuition pumps” — Dennett’s name for thought experiments designed to guide us toward an apparent intuitive truth — like Nagel’s bats, which seem profound at first glance but collapse into nonsense when considered seriously.

Since the publication of Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (2006), Dennett has been closely associated with prominent atheists (he prefers the term “brights”) such as Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, and the association has brought him wider attention than an American philosopher of mind might otherwise expect. Within the world of academic philosophy and cognitive science, however, he was a household name long before then. In this more rarefied space, Dennett’s star-making turn was Consciousness Explained (1991), a book that aimed to provide “the beginnings of a theory — an empirical, scientifically respectable theory — of consciousness.”

“A mystery,” Dennett writes early in Consciousness Explained, “is a phenomenon that people don’t know how to think about — yet.” He goes on to note the many mysteries — such as the emergence of life and the appearance of design in nature — that were once assumed to be unsolvable in much the same way that consciousness is now. We still don’t know everything there is to know about time or the origin of the universe, but we have figured out the right way to think about them, so we have tamed their mystery. Why should consciousness alone be immune to this process?

Any effort to tame the mystery of consciousness, Dennett says, must be materialist in nature. Why? Because giving a materialist account is what he means by taming the mystery:

It is not that I think I can give a knock-down proof that dualism, in all its forms, is false or incoherent, but that, given the way dualism wallows in mystery, accepting dualism is giving up.

The first step in constructing the materialist alternative is to do away with one of our most strongly held intuitions — the idea that no one could ever really observe anyone else’s consciousness. Dennett believes he’s found a method for the objective study of consciousness, which he gives the forbidding name of heterophenomenology but which basically amounts to asking people about their subjective experience and (mostly) taking them at their word.

It doesn’t seem at first blush that verbal reports on conscious states could be suitable stand-ins for the conscious states themselves. Aren’t qualia essentially ineffable? (How would one describe the experience of seeing redness to a blind person?) But this is another strongly held intuition that Dennett seeks to overthrow. Not only does he believe that verbal reports can convey consciousness — at least, adequately for empirical study — he eventually comes to argue that consciousness is precisely a series of such verbal reports. There is something that it is like to be a human because we are constantly asking ourselves what it is like and constantly answering the question. (Dennett is notable among philosophers for his interest in computer science and artificial intelligence, and the similarity between heterophenomenology and Alan Turing’s Imitation Game is no coincidence.)

There is a common assumption — related to the intuitive sense that bats and other mammals must have some kind of inner phenomenological life — that human consciousness precedes human language, both in individuals and in the evolutionary history of the species as a whole. First we have conscious states; later we develop the means to describe those states (in approximate terms) to others. Dennett reverses this assumption by way of an evolutionary just-so story that begins with early hominids engaging in the sort of proto-speech-acts exhibited by other primates, asking one another for help or information and eliciting proto-speech-acts in return.

Then one fine day (in this rational reconstruction), one of these hominids “mistakenly” asked for help when there was no helpful audience within earshot — except itself! When it heard its own request, the stimulation provoked just the sort of other-helping utterance production that the request from another would have caused. And to the creature’s delight, it found that it had provoked itself into answering its own question.

Dennett invites us to imagine an evolutionary process by which this self-asking became a common strategy. Eventually someone would recognize the benefit of self-asking without vocalizing the question, and thus an internal conversation would develop. (In Dennett’s telling, there is even an intermediate step, in which the utterances are spoken sotto voce.) Over time, the human brain evolved into a “Joycean machine,” in which the constant babbling from various sources turned into the stream of consciousness. It became a host for words.

It’s deeply strange to think of this internal conversation giving rise to consciousness. First, there is the odd idea that one part of the brain could “know” something — consciously know it, such that it can generate a speech-act about it — while another remains in ignorance. Granting that such asymmetry is possible, which part of the brain needs to have the information in order for us to be conscious of it? Lurking behind this question is the one assumption that Dennett is most eager to be rid of — the idea that there is a single place in the brain where conscious experience happens:

Let’s call the idea of such a centered locus in the brain Cartesian materialism, since it’s the view you arrive at when you discard Descartes’s dualism but fail to discard the imagery of a central (but material) Theater where “it all comes together.”

In place of the Cartesian Theater, Dennett offers the Multiple Drafts model. All manner of mental activity happens simultaneously throughout your brain, in this model, and “information entering the nervous system is under continuous ‘editorial revision,’ ” constantly being accessed from different parts of the brain, interpreted, and combined with other information from other parts. Millions of “word-demons” in the brain fight quasi-Darwinian battles to be the one we are conscious of at any given moment. Most of the time this process appears seamless to us, but this seamlessness is something like the user illusion by which computers cover up all the processing they’re doing and offer us a “desktop” with “files” on it. We occasionally happen on one of the seams, though, as when we find ourselves suddenly noticing something we’ve been staring right at for several moments.

Consciousness Explained does a remarkable job constructing a functional alternative to the Cartesian Theater, but it is less successful at convincing readers that this alternative has rendered the “hard problem” moot. Indeed, many of Dennett’s metaphors invite Cartesian-materialist questions about who is reading the draft, using the desktop computer, listening to the Joycean babble. Dennett is aware of this risk, and he warns us against it. There is no conscious agent “reading” the multiple drafts, he says. The drafts are the conscious agent. However, he defers explaining exactly how this could be so. He is such a lucid thinker on the topic that one is eager for the moment when he will make that leap. After reading several hundred meticulously researched and rigorously argued pages, it is slightly demoralizing to arrive at this passage:

If consciousness is something over and above the Joycean machine, I have not yet provided a theory of consciousness at all, even if other puzzling questions have been answered.

Until the whole theory-sketch was assembled, I had to deflect such doubts, but at last it is time to grasp the nettle, and confront consciousness itself, the whole marvelous mystery. And so I hereby declare that YES, my theory is a theory of consciousness. Anyone or anything that has such a virtual machine as its control system is conscious in the fullest sense, and is conscious because it has a virtual machine.

Well, he hereby declares it — there is your scientifically respectable empiricism at work.

Dennett knows this conclusion isn’t entirely persuasive, but he believes it ought to be enough to “shift the burden of proof” away from the materialists and back to the mysterians. Remember, dualism means giving up, so a materialist account does not have to be ironclad to be preferable. “My explanation of consciousness is far from complete,” he admits.

I haven’t replaced a metaphorical theory, the Cartesian Theater, with a nonmetaphorical (“literal, scientific”) theory. All I have done, really, is to replace one family of metaphors and images with another.

There is an agreeable modesty to this conclusion, especially given Dennett’s usual rhetorical pitch. (A book titled A New Family of Metaphors for Thinking About Consciousness might not have caused the same stir as Consciousness Explained.) But there is a sense in which the reliance on such metaphors goes a long way to proving the mysterians’ point. A geneticist might use all sorts of metaphors to explain the replication of DNA, but at a certain point she can also put a strand under a microscope and show you what is happening. Dennett knows a great deal more than most of his opponents about the physical workings of the brain, and his effort at bringing this knowledge to bear on what might otherwise be another late-night dorm-room bull session is admirable. But ultimately he agrees with his opponents on one central point: the unified self most of us experience ourselves as being has no basis in the physical brain. Rather than attempting to circle the square, Dennett wants us to give up this idea of the self. That leaves him in a position familiar to many brights: he is trying to prove a negative.

This realization may account for the direction Dennett’s career has taken since Consciousness Explained. He has continued to contribute prolifically to academic journals and remained a close observer of the latest work in artificial intelligence and machine learning, but his subsequent books have been geared toward a general audience, and they have seemed designed to engender the habits of mind that might create receptive hosts for his new family of metaphors. He followed Consciousness Explained with Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (1995), which showed how the powerful algorithmic process of natural selection could not just explain everything from biological diversity to human culture but even offer us a form of naturalized ethics. This evolutionary view of culture was narrowed to religion in Breaking the Spell. After this came Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking (2013), a book that recapitulated much of his evolutionary argument to teach its readers how to think straight.

The story of how evolution could give rise to human minds — and by way of them to human meaning, human values, and human culture — has always been a component of Dennett’s theory, but it has become more and more important to his argument, as though he suspects, perhaps correctly, that the final remaining justification for Cartesian thinking is the intuitive sense that nothing as wondrous as human experience could really be susceptible to a purely natural explanation. Whereas to many, a theory of the evolutionary basis of consciousness would naturally follow once we had our physical explanation for the phenomenon, Dennett turns the problem around. If he can finally convince us that the blind process of evolution can give us consciousness and all the things that consciousness brings into the world, we might lower the last defense and recognize the obvious appeal of his physical model.

This project has come to its own culmination in From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds, which Dennett himself seems to view as his last, best shot:

I have devoted half a century, my entire academic life, to the project in a dozen books and hundreds of articles tackling various pieces of the puzzle, without managing to move all that many readers from wary agnosticism to calm conviction. Undaunted, I am trying once again and going for the whole story this time.

To this end, there is a great deal in this new book that will be familiar to Dennett’s regular readers. There is the encyclopedic knowledge of both the history of and the latest thinking in philosophy, evolutionary biology, psychology, and computer science. There is the usual flair for analogy and professorial dad jokes. (Technology has changed in the past twenty-five years; now words are apps that are “installed in our necktops.”) There is also the somewhat aggrieved sense that those who don’t agree with him lack the courage to think honestly about things, and a particular impatience with the self-described materialists among them, who ought to know better. (Here they are not “Cartesian materialists” but, even worse, dualists “in disguise.”)

What distinguishes Bacteria to Bach is its treatment of meme theory, which has long been present in Dennett’s work but here takes center stage. Memes are having a moment right now, so it’s worth clarifying that the notion of such entities was first put forward more than forty years ago, long before the age of the GIF. In The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins noted that the process of evolution through natural selection requires very little to get going. Wherever there are entities that replicate themselves with minor variations in an environment that differentiates the survival chances of these variations, the process will occur. Dawkins’s book popularized the idea that in the case of organic life, the relevant replicators are not groups or species or even individual organisms but genes, which use organisms as carriers enabling their safe replication. Dawkins acknowledged that his gene-centered theory did a poor job of accounting for culture, which is not genetically programmed and often seems to work against genetic interests. (Think of contraception or monastic celibacy.) To fill this gap, he proposed the existence of a kind of cultural replicator that exhibits the characteristics necessary to set off an evolutionary process:

Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation.

This idea has proved very powerful — one might say the “meme” meme has proved a very adept replicator. To some thinkers, meme theory provides a useful metaphor for understanding how culture works, but others take a more literal view. Dawkins quotes a colleague, N. K. Humphrey, on the meme for belief in an afterlife — it “is actually realized physically, millions of times over, as a structure in the nervous systems of individual men the world over.”

Since Dawkins first set out meme theory in a somewhat speculative fashion, Daniel Dennett has become perhaps its leading proponent. In fact, he has greater faith in the theory than Dawkins himself does. In Dennett’s opinion, Dawkins has undersold the importance of memes, and of one type of meme in particular — the word. “Words,” he argues, “are a kind of virtual DNA.” Meme theory pushes Dennett’s view of language as crucial to the development of consciousness one step further: in the process of leaping from brain to brain, the argument goes, memes turn those brains into minds. Just as organisms exist to carry around self-replicating genetic code, minds exist to carry around self-replicating memes. Furthermore, it is thanks to memes, Dennett argues, that humans became “the only species that has managed to occupy a perspective that displaces genetic fitness as the highest purpose, the summum bonum of life.”

This argument is certainly present in Dennett’s earlier work, but in Bacteria to Bach he emphasizes to a much greater degree the radical differences between gene-based evolution and the more recent meme-based sort: “Once words are secured as the dominant medium of cultural innovation and transmission,” he says, they “begin to transform the evolutionary process itself.” Through the power of language, minds eventually became capable of consciously selecting some memes over others, something the “blind watchmaker” of nature could never do. Darwinian evolution gives us “design without a designer,” but once that undesigned process brings designers into existence, it becomes “de-Darwinized,” that is, it stops being random and undirected. All the things that human minds entail — meaning and intention and values — come to play a role.

In a sense, this is all still a product of natural evolution, since it arose from that process. It’s just that evolution itself has evolved. To use one of Dennett’s favorite analogies, cultural evolution is a crane built on a crane, not a free-floating “skyhook.” But the implications are curious. Dennett has long argued against treating consciousness as a special case: “Why should anyone expect that consciousness would bifurcate the universe dramatically, when even life and reproduction could be accounted for in physico-chemical terms?” Yet the reliance on meme theory seems to suggest that physico-chemical terms will not suffice to account for human minds.

The problem gets even harder when one stops to think about the ontological status of memes themselves. Do they exist in the way that strands of DNA do? Dennett has a simple answer to this question. “Memes exist because words are memes, and words exist. . . . If you are one of those who want to deny that words exist, you will have to look elsewhere for a rebuttal.” Like many of us, Dennett is generally at his most peremptory where his argument is weakest — he hereby declares it — and this is a particularly weak point. There is certainly a sense in which the words on this page (or screen) exist in a physical form, as do the waves of light that reflect from this page to strike your eye while you read. This light induces your brain into what are unquestionably physicochemical states. But when we try to put ink and light and brain state under the same ontological banner — indeed, propose that the second and third are replicas of the first — we run into something very close to the mind-body problem that set us on this road in the first place. An exhaustive physical account of ink and light and brain will not tell us the content of that word. For that we need minds.

Of course, Dennett knows this — his theory rests on the fact that memes need minds to survive — but it doesn’t trouble him. The words being produced in your mind as you read are not, Dennett allows, physical replicas of the words I am writing right now,

but they are — we might say — virtual replicas, dependent on a finite system of norms to which speakers unconsciously correct their perceptions and utterances, and this — not physical replication — is what is required for high-fidelity transmission of information.

This is where Dennett leaves us — with a vision of a virtual realm governed by human norms, a realm in which evolutionary principles prevail but the units of replication are not physical in nature. It’s a strange place to arrive after half a century of materialist thinking. At least it has no hints of Cartesian materialism. If it didn’t mean giving up, we might call it Darwinian dualism instead. ?