Early this May, the temperature in Phoenix reached 106 degrees Fahrenheit — the sort of dry, searing heat that locals don’t expect until deep summer. On May 8, when it had cooled to a comfortable 83, the students walking between classes at Mountain Sky Junior High School seemed relieved. Mountain Sky is at the north end of Phoenix, just off West Greenway Parkway, a road that draws a dividing line: On one side, there are dozens of modest single-family-housing complexes spreading into the distance, their roofs terra-cotta and stucco, their back yards appointed with turquoise pools. On the other, there is a mobile-home park where stained furniture has been strewn about, discarded.

Katie Piehl, who attended Mountain Sky as a child, has been teaching English language arts to special-education students there for five years. During a break, she led me across a courtyard that was flooded with light. Her classroom is not in the school’s main building but in one of several detached trailers near the back of the campus, a result of overcrowding. There would be no sunshine when we got inside, she warned — the room didn’t have windows, just a couple of slits in the wall, and one of them was covered up. That was an intentional design feature, she said, to keep the cost of air-conditioning at a minimum.

Piehl is thirty-three, with shiny shoulder-length hair recently dyed red and dimples in her smile. She wore silver earrings that swung like wind chimes. When we entered her classroom, it was dim; she opted to keep the harsh fluorescent overhead lights off, relying instead on a mismatched set of lamps that she had collected over the years from garage sales and dumpsters. The lamps also served as grow lights for the leafy plants that covered nearly every table and shelf, to give the place charm. In a corner near the front were beanbag chairs, also bought by Piehl, on which students could sit and relax during independent reading time. At the back, she had assembled a library, largely from a local secondhand store.

The bell rang and her students filed in. They were a playful bunch of eighth graders; all had disabilities, and most were Latino, though Mountain Sky’s overall population is more diverse. The kids who had filled out their planners with that week’s assignments received stickers, which Piehl had acquired for free. “They will work for stickers,” she told me.

Then she led the class in a debate. The students were encouraged to submit questions about topics important to them; each day, she selected one to pose to the group, and they expressed their support or dissent by gathering at opposite walls. On one side of the room was a laminated poster that read yes; on the other, no. Today, Piehl had selected a difficult question from the only black student: “Is racism a problem in our school?” All but one of the kids walked over to stand on his side. “I don’t want to come across as a person really angry about this,” he said. “But I have had experiences where I’m walking up and people just say the N-word out of nowhere, or say, ‘Go back to the cotton fields.’ ”

The conversation continued, with more testimonies about stereotypes and discrimination. The lone dissenter, a girl with wavy brown hair, admitted to feeling conflicted as her peers spoke about unfair treatment they’d known. On another wall, I noticed, Piehl had pinned up covers that her students had designed for William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, a story about children who must fight for scarce resources. Many of them showed the bloody head of a pig.

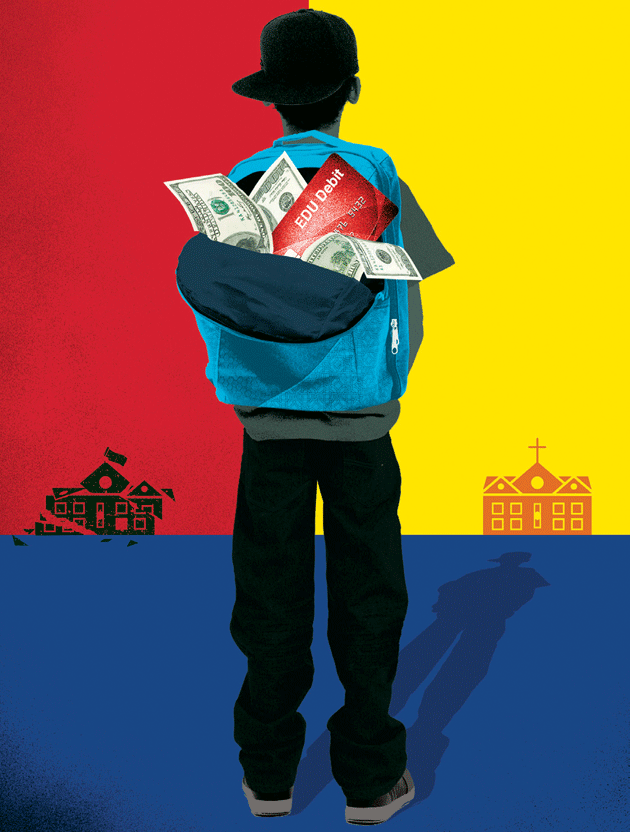

This spring, while public school districts serving minority families and disabled children couldn’t afford basic supplies or comforts, Arizona’s legislature approved the broadest, most flexible interpretation of what Betsy DeVos, the secretary of education, and her allies tout as “school choice.” Governor Douglas Anthony Ducey, buoyed by fellow Republicans on both sides of the statehouse, signed a law expanding Empowerment Scholarship Accounts, Arizona’s take on school vouchers. Typically, vouchers use tax dollars to pay private institutions; through E.S.A.’s, money that could otherwise fund public education is loaded directly onto debit cards that select parents can use to subsidize private tuition and related expenses. Similar programs exist elsewhere — in Florida, Mississippi, and Tennessee — though those limit eligibility to families with children who are disabled; Nevada developed an unrestricted program, but courts have blocked its funding. More than any other state, Arizona has managed to bolster E.S.A.’s as a way to advance alternatives to traditional schooling. That makes it a model for conservatives across the country, yet Piehl and her colleagues view the legislature’s decision as the latest example of a disturbing trend: divestment from public education.

In 1871, Anson P. K. Safford, the governor known as the father of Arizona’s public schools, proposed a bill that would organize counties into school districts and levy property taxes to cover the cost. Public education was necessary for all (white) American children, he believed, in order to distinguish them from the Apache. Legislators resisted the tax increase but eventually passed a version of the bill that taxed ten cents on every hundred dollars of property, to be set aside for a school fund. Later, when an attempt was made to split the fund between public and sectarian schools, Safford condemned the idea. Doing so, he said, “could only result in the destruction of the general plan for the education of the masses, and would lead, as it always has wherever tried, to the education of the few and the ignorance of the many.”

The school choice movement — a clever term for which, like “pro-life,” there is no reasonable opposite — arrived in Arizona a century later, reigniting the old debate about the role of public money in private education. Its breakthrough, charters, was the brainchild not of Republicans or so-called school reformers but of Albert Shanker, the president of the American Federation of Teachers. In 1987, he visited a public school in Cologne, Germany, which had abandoned its country’s rigid academic tracking system and given teachers direct control over their curricula. As students advanced, their teachers followed them. Classrooms were more diverse than those in traditional schools, and students were of mixed ability. The school was a success, and it inspired Shanker to propose teacher-driven laboratory classrooms in the United States. Naturally, he imagined charter schools as places where teachers could enjoy great autonomy and would be firmly unionized. The response from Republicans of the era was lukewarm, to say the least. William Kristol, founder of The Weekly Standard, who was then employed by the federal Department of Education, assured Shanker that “traditional methods are working.”

Over time, however, conservatives found that charter schools could be useful as a means to promote open-market principles in education. In 1991, Minnesota passed America’s first charter school law, striking a deal with reformers in which taxpayers would fund “innovative” schools not bound by state curricular requirements or accountability standards. The floodgates opened, and the charter system ultimately deviated sharply from Shanker’s vision. Arizona passed its charter law in 1994, and during the first year, the Department of Education received as many as 400 applications from individuals and groups seeking to open schools. Today, more than 500 charters — both not-for-profit and for-profit — operate throughout the state.

Over time, however, conservatives found that charter schools could be useful as a means to promote open-market principles in education. In 1991, Minnesota passed America’s first charter school law, striking a deal with reformers in which taxpayers would fund “innovative” schools not bound by state curricular requirements or accountability standards. The floodgates opened, and the charter system ultimately deviated sharply from Shanker’s vision. Arizona passed its charter law in 1994, and during the first year, the Department of Education received as many as 400 applications from individuals and groups seeking to open schools. Today, more than 500 charters — both not-for-profit and for-profit — operate throughout the state.

In 1997, Arizona further expanded its school choice offerings by passing the nation’s first tax-credit program for education. Through this program, people could donate money to nonprofit organizations that had established scholarships for kids to attend private schools; the donor would receive a dollar-for-dollar tax break, a benefit initially expected to cost the state $4.5 million per year.

Private schools receiving funds this way, many of them religious, began to increase their tuition and publish step-by-step guides instructing parents in how to apply for the scholarships. (Among these schools was Northwest Christian, in Phoenix, whose elementary science and social studies curricula were developed by BJU Press, a creationist publishing house.) Over the years, the legislature passed bills to expand the program — including one that enabled companies to participate — and the tax breaks eventually topped $140 million. Between 2010 and 2014, one group, the Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization, received $72.9 million in donations, triggering the same amount in tax breaks. By law, such organizations are allowed to keep 10 percent of donations to pay for operational costs, and in 2013, according to IRS filings, the executive director of Arizona Christian received $145,705. The executive director, as it happens, was Steve Yarbrough, a Republican who is now the president of the state senate. His earnings were reported to the public; the tax-credit program nevertheless continues to thrive.

Arizona’s foray into vouchers had a more troubled start. The first attempt, in 2006, was ruled unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court because it deposited public money directly into the coffers of private schools. But in dismissing the program, the court did not reject its creed: Justice Michael D. Ryan wrote that choice advocates had been “well intentioned,” and suggested that there might be a way for tax dollars to send special-needs students to private or religious institutions. At the time, an organization called Alliance for School Choice was operating in Phoenix; it would later move to Washington under the name American Federation for Children, with Betsy DeVos as its chair. Sydney Hay, a lobbyist for the firm, told me that Ryan’s response provided a “road map.” She and her colleagues formed a working group to analyze the decision, and soon had their “eureka moment.” Justice Ryan had pointed the way to what would become Empowerment Scholarship Accounts.

The E.S.A. program became law in 2011. Although the system was pitched to serve disabled children, in the years that followed, legislators, goaded by a rising number of school choice lobbyists circling Phoenix, gradually expanded eligibility. Accounts were made available to those enrolled in or living within the zones of schools that earned D or F letter grades on their state report card; children of active-duty military personnel or of the legally blind, deaf, or hard of hearing; students living on Native American reservations; children in foster care; and siblings of qualified applicants. Arizona is now home to about 480 private schools — nearly 60 percent of which have religious affiliations (predominantly Christian) — serving some 64,000 students.

When Hay started working on school choice reform, “It was a free-market argument, which of course pits Republicans versus Democrats,” she told me. She and her cohort have since found success by approaching vouchers as a social justice concern, she said. “In the beginning, it was, ‘Oh no, these are going to be the death of public school education.’ That opposition is pretty much over.”

As Arizona has become a hub for school choice, funding for traditional public education has been depleted. More than a million school-age children live in the state, and 85 percent of them are enrolled in public schools. Unlike most states, Arizona has borderless districts — students may attend whatever school they like, regardless of where they live. Mountain Sky is in one of the largest districts and receives federal Title I funding, which offers aid to schools with a predominance of students from low-income or impoverished families.

When Piehl took me through the lobby, she pointed out a large fish tank. Mountain Sky’s STEM program — a draw, she told me — has fun with it. But the tank, like so many other learning tools — there, and in schools around the country — has depended largely on teachers who use their free time looking for ways to collect money and on parents who have the means and the inclination to donate. The STEM teacher who brought in the tank had to apply for a grant to pay for it. Piehl did the same when she wanted to set up a garden for her students. Using sites like Donors Choose, other teachers have raised money to provide an early-morning aerospace class, 3-D printers, and laptops. Many expenses remain beyond reach. Trailers aside, the social studies textbooks are outdated and missing pages; last year, Mountain Sky was unable to offer foreign language courses.

Piehl and her colleagues are accustomed to public education’s commonplace, workable hardships; according to the most recent state report card, Mountain Sky earned a B. But in less fortunate areas, the circumstances are dire. Last year, in the nearby Glendale Elementary School District, two schools shut down for weeks after workers discovered that the buildings were not structurally sound; hundreds of students were forced into temporary classrooms. Glendale has since become one of several lead plaintiffs in a lawsuit against the state. The complaint, filed in May to Maricopa County Superior Court, cites the loss of about $18.9 million in promised funds between 2009 and 2015.

The battle over capital funding in Arizona is part of a larger struggle in public education, in which teachers must vie for support through litigation. In 1994, the same year that charter schools were introduced, Tim Hogan, an attorney with the Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest, won a lawsuit against the state that challenged its practice of relying on districts to pay for public school maintenance through tax hikes and bonds. Such measures require voter approval, and in some communities teachers had been going door-to-door asking neighbors to increase their taxes. Low-income and rural areas had little or no capacity to pass bonds and overrides, Hogan argued, putting them at a disadvantage relative to their wealthier suburban peers.

For years, the state failed to otherwise deliver the necessary cash. In 1998, the legislature passed the Students FIRST (Fair and Immediate Resources for Students Today) Act, which provided $1.3 billion to upgrade deficient buildings and set a formula to provide at least $100 million annually for maintenance. But much of that money never appeared. Within ten years, promised payments were suspended, and when the country was plunged into a recession, Jan Brewer, the Republican former governor, began to slash the budget for “soft” capital (technology, furniture). Eventually, the statehouse voted to bail on its annual maintenance pledge altogether, and instead established a grant for which desperate schools could apply.

As a result, teachers have been forced to continue canvassing. Piehl told me that she has done so on at least fifteen occasions. Most recently, her district had a request on the ballot last November for a bond that would improve technology and transportation, plus pay for structural upgrades to school buildings. She hoped that the construction could move her students into a real classroom. “It’s like we’re begging every time,” she told me. “And I hate being that person. A lot of voters are like, we get it, we’re voting yes. But then when you get those people that just don’t understand, it’s so defeating. It feels like berating to have to constantly go out and ask for more, more, more.” The bond was approved, though Piehl is still not sure whether she’ll get out of the trailer.

While the statehouse was starving the budget for infrastructure, Hogan filed another lawsuit, this time alleging that officials had cut inflation adjustments for its per-pupil funding formula. According to the Census Bureau’s latest available count, Arizona ranks forty-ninth in state-provided per-pupil spending, offering just $7,489. (New York, the biggest spender, provides $21,206.) Arizona barely outranks Idaho, which has, as a cost-cutting measure, reduced the school week in some districts to four days.

The inflation lawsuit took years, and public education continued to languish. In 2015, Arizona officials devised a solution: Proposition 123, which would, in the next decade, pay schools $3.5 billion. That amount would cover about half of what the state had previously withheld (by Hogan’s count), plus what it would owe over time with the proper inflation adjustment. The measure was added to a special ballot, in May 2016, and without a better alternative, voters narrowly approved it.

The passage of Prop 123 was an unsatisfying victory for people working in public education. The average starting salary for a teacher in Arizona is $31,874, and the compensation for elementary school teachers there, when considering the cost of living, is the lowest in the country. According to the Arizona Republic, teachers in the Peoria Unified School District, for example, were looking at a raise of $53 every two weeks. Some cross the border to California or Nevada in search of better wages; nearly 90 percent of teachers recruited to Arizona leave within five years. With 24 percent of the education workforce eligible for retirement, the state is facing a severe teacher shortage. Most districts pledged to use their Prop 123 money to increase teachers’ salaries in an attempt to keep them in the classroom.

In January, Governor Ducey vowed that in his budget for the 2018 fiscal year teachers would see their compensation go up. His plan factored in already-scheduled payments to schools (a result of Prop 123), along with $114 million in new spending. “If you take all of this money combined,” he told the local NBC affiliate, “there is the potential for a ten-thousand-dollar raise for each of our teachers. Now, our schools have needs in addition to that, but there are dollars there to see our teachers get raises. That’s left to our principals and superintendents to do it.”

Ducey’s estimation was rather optimistic. The final state budget, passed in May, included a meager 2 percent raise for teachers, spread over two years. Not a single Democrat voted in favor. That same month, Hogan filed yet another lawsuit against Arizona’s government, arguing that its school finance system is unconstitutional.

One morning, I met Steve Farley, a Democratic state senator, in his office. Farley, at fifty-four, is tall and wears black-framed rectangular glasses. His office was filled with photographs he had taken of the Arizona desert; when he’s not at the capitol, he runs a graphic design company from his district, in Tucson. His two daughters attended public schools there. At Tucson High School, he said, 10 percent of classrooms are uninhabitable because building-renewal funds have been slashed. Not long ago, when one of his daughters’ English teachers lamented her inability to teach The Kite Runner (the district’s sole set was unavailable), he went out and bought forty copies. “But parents shouldn’t be the ones buying books for classrooms,” he said. “That’s our duty, and we have been derelict of that duty.”

Farley, who announced in June that he would challenge Ducey for the governor’s office next year, was the child of public-school teachers. “Teachers are dedicated to their career,” he told me. “They’re dedicated to their kids. They want to help. It’s a crusade for them. And they’re willing to do it, no matter how badly they’re treated. But we’re reaching the end of their ropes.”

The Phoenix Mountains Preserve is a sprawl of desert peaks and rocky, arid valleys crisscrossed by trails. At its base is Gateway Academy, a private school for “twice exceptional” children — students with Asperger’s syndrome (high-functioning autism) who are also academically gifted. When I visited, all seventy-five pupils were gathered in the gym for their morning meeting. A small boy was leading everyone in silent meditation. Gateway’s executive director, Robin Sweet, led me around the campus: a two-story building flanked by a desert tortoise habitat, a vegetable garden, and a pavilion with a misting system for especially hot days. A large sports field was filled in with either Bermuda grass or ryegrass, depending on the season.

Sweet told me that her son Nikolai has Asperger’s. He showed early signs of curiosity and intelligence, but once he entered kindergarten he had a hard time with structure. He changed schools frequently; a psychologist said that he had ADHD; teachers would hand Sweet pink slips for his bad behavior. “You start slinking down,” she recalled. Nikolai was diagnosed with Asperger’s when he was ten, and by that time he was enrolled at a private school. When the director announced plans to sell, Sweet and her husband decided to take it over. Under their leadership, the focus was narrowed to serve only children with the same needs as their son. “How do you educate all those different learners under one roof? Well, you don’t.” Sweet went on, “A lot of the parents were spending all of their free time taking these kids to occupational therapy and speech and language and equine therapy. This is exhausting.” The Sweets would take care of everything; at Gateway there is a “sensory room” where therapy sessions are held in private tents.

In the gym, she introduced me to Antonio Gipson, who was about to graduate. Antonio, tall and athletic, wore a Gateway T-shirt. He had enrolled in 2015, after years of languishing in public and charter schools around his hometown of Tempe. “The mind-set was, ‘We’re not here to teach you,’ in a sense, ‘We’re here to prepare you for college,’ ” he told me. “You either sink or you swim. I struggled and gave up on it.”

When Antonio’s grandmother learned about Empowerment Scholarship Accounts from a colleague, she pounced. Families seeking an E.S.A. simply submit a two-page form to the Department of Education. Last year, about two thirds were accepted — though that rate is likely to change now that the remaining restrictions have been lifted, and any family with savvy and prep school ambitions may apply. Once a request has been successfully processed, the state issues a debit card loaded with money that parents can use for tuition and fees (including uniforms, labs, and books), homeschooling expenses, online classes, therapy if the student has a disability, tutoring, and standardized tests. The card cannot be used for everything — bus fare and lunch money are excluded. In the most recent school year, 3,500 students participated in the E.S.A. program, a majority of whom had special needs. On average, students who had no diagnosed disabilities received $5,700, and those who did got $19,000. According to a report by EdChoice, a pro-voucher group, most of that money was used to pay for private schools. The Gipsons were provided with $25,500, which covered Antonio’s full tuition at Gateway.

Gateway offers twenty-two world languages (taught under the guidance of an instructor using the Rosetta Stone program), and Antonio cheerfully demonstrated how he introduced himself in Japanese. Then he said, “When I came here, with the smaller class sizes, you get way more help than you would in a district or even a charter school. When I realized the level at which I was able to succeed, I became more confident. Then, you know how you get that mind-set where you speak something into existence? That’s what it turned into. Since then it’s not necessarily a cakewalk, but it’s been easier.” He made friends, started playing basketball, and joined the National Honor Society. A few weeks after we met, he was named valedictorian, while Sweet looked on, beaming.

Antonio, I learned later, had become a poster boy for Arizona’s school choice advocates. In January, he gave a speech before the legislature, telling members that his E.S.A. had turned his life around; other Gateway kids were brought along to fill the chambers. His story is moving, if not entirely representative. Although E.S.A.’s are still advertised as a solution for disabled children of color trapped in “failing” schools, the Arizona Republic found that more than 75 percent of last year’s funding diverted from public schools to these accounts came at the expense of districts with an A or a B on their state report card. More students from wealthy communities have taken advantage of the program than students from poor ones — possibly because when the awarded amount does not entirely cover private tuition, parents must make up the difference. Transportation costs can also thwart students from low-income backgrounds. Last year, a meager 4 percent of E.S.A. kids came from districts with a grade of D or below, and the amounts they received tended to be lower than those of their peers.

For years, critics have expressed concerns about the system’s lack of oversight. A woman in Chandler, a suburb of Phoenix, was indicted on charges that she had used her sons’ E.S.A.’s to buy a high-definition television, a smartphone, and two tablet devices, and allegedly to pay for an abortion. A couple with children enrolled in the program bought approved educational items that they later returned for store credit; in exchange, they took home a stuffed animal, a snow globe, a World of Warcraft calendar, and a Walking Dead board game. Others have used E.S.A. money on dating websites, hotel rooms, and fast food. Since the program’s debut, regulations have been introduced to rein in abuse. But in June 2016, a state audit found that, over a recent six-month period, parents had misspent more than $102,000 in E.S.A. money, and less than a quarter of it had been recovered.

The audit couldn’t stop the E.S.A. program from growing. The latest expansion bill was introduced by Debbie Lesko, a Republican state senator, who invited me to her office. She has blue eyes and long, straight blond hair. That day, she was wearing a beige skirt. “My question to the opponents,” she said, “is, why would you not want to give parents a choice to find the best education for their child?” She dismissed claims that E.S.A. money has been siphoned from public schools, and drew me a diagram on scrap paper to help explain the state’s complicated education-funding system. By her math — which she repeated over the months of legislative wrangling — the program would save taxpayers as much as $4,300 per student.

But the state’s nonpartisan Joint Legislative Budget Committee released a report refuting her accounting. Their estimate had the E.S.A. program costing Arizona an extra $24 million by 2021. Lesko made adjustments to her bill, and upon seeing the new numbers, the J.L.B.C. determined that the program could save money if it had a cap. The legislation that passed in April set a cap on enrollment, but after the vote, the Goldwater Institute, a leading school choice group, sent an email to its supporters pledging that the cap would be lifted. Parents began collecting signatures to undo the law with a referendum; the Peoria Unified School District, which Lesko represents, voted to formally denounce the program, and a few protesters picketed outside her house. When I asked her about the response, she said, “It’s not fun to have people calling me names and saying I’m a devil for what I believe in, but I just keep fighting.” She recently called on unions to drop the “over-the-top” reaction to vouchers and embrace “educational options.” She told me, “Otherwise, it’s just a monopoly.”

The E.S.A. program has become part of a national debate over the relevance of facts in policy-making. “The expansion is really not about choice, because Arizona already has unlimited choice — families can go wherever they want right now,” Tim Ogle, the executive director of the Arizona School Boards Association, told me, referring to the borderless districts. “It’s about privatization, which is very different conceptually.” He went on, “The expansion has to do with public money in private schools, where there’s no accountability, financially or educationally.”

Ogle conceded that the needs of some disabled students can’t be met in public schools. But such a significant investment in a private system won’t help most of them. “We have great evidence that these voucher programs have really harmed children,” he said.

When Governor Ducey signed the new E.S.A. bill into law, he did so in the absence of any studies evaluating its effectiveness. Across the country, there has been relatively little long-term research examining voucher programs, and the findings that do exist are at best mixed. In Milwaukee, a report found that while some voucher kids are more likely to graduate on to a four-year college, there is little to support the notion that, on the basis of test scores, they are better prepared. A recent study of Indiana’s program, which was expanded while Mike Pence was the governor, discovered that students saw drops in math scores, and did not improve in reading until they spent at least four years in private school. In April, the U.S. Department of Education released an analysis of the program in Washington, D.C., the nation’s only federally funded voucher system. The results were grim: Students who used vouchers earned markedly lower scores on math tests in their first year compared with those who applied but did not receive a voucher. Children in kindergarten through fifth grade also had lower reading scores. Secretary DeVos defended the program anyway, insisting that parents overwhelmingly support it.

The election of Trump, and DeVos’s confirmation, has effectively made school choice into national policy. The vouchers, education savings accounts, and tax-credit programs that already exist are poised to grow. This year, thirty-five states have introduced bills that would either create or expand school choice programs. On the federal level, DeVos’s education budget proposal includes $9.2 billion in cuts. (If implemented, it will gut teacher preparation and professional development, after-school programs, Special Olympics activities, American history, and the arts, among other things.) She will instead finance her school choice priorities, namely a $250 million increase in scholarships that send kids to private (including religious) schools and a $1 billion infusion to the Furthering Options for Children to Unlock Success (FOCUS) program, which sends money to districts that do away with zoning and adopt open enrollment — as Arizona does.

In June, DeVos’s camp received judicial validation. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Trinity Lutheran Church Child Learning Center, in Missouri, which sought public funds to build a playground. “We should all celebrate the fact that programs designed to help students will no longer be discriminated against by the government based solely on religious affiliation,” DeVos cheered. In the dissent, Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justice Ginsburg, wrote that the decision “slights both our precedents and our history, and its reasoning weakens this country’s longstanding commitment to a separation of church and state beneficial to both.”

When DeVos is called on to provide specifics or address concerns about her platform, she tends to fumble. During a Senate hearing on her department’s budget, when asked whether schools participating in a national voucher program would be punished for unfair treatment of L.G.B.T.Q. or disabled students, her first answer was not that she opposed all forms of discrimination. She could muster only one reply, repeated fourteen times: “Schools that receive federal funds must follow federal law.” Her response was especially distressing given that Trump has rescinded an Obama-era guidance instructing schools to interpret Title IX, a federal law against discrimination, as extending to trans students. She also failed to answer questions about legal requirements for special-needs children. Millions of parents took note.

One of them was Michelle, a mother in central Arizona who several years ago signed up for an E.S.A. Her son has autism. When she brought him to private school for second grade, she was surprised to find that his teacher held no state-certified credentials to teach special education — training that is mandatory in public schools but unregulated at private institutions. As the semester went on, parents received little information about their children’s academic progress. The school gave few assessments and, at the time, was not required to administer state tests. “It was hard to get a real gauge on where he was academically,” Michelle said of her son. “In the private school it was kind of like, ‘Everything’s great!’ Well, everything can’t be that great. I know what kinds of questions to ask, and I didn’t always feel like I was getting the most accurate reflection of my child.” (Under the latest version of the law, private schools receiving E.S.A. funds will now have to give state tests, but many won’t be required to make scores public.)

When Michelle voluntarily enrolled her son in a private school, she had waived his right to a personalized plan for education and support, guaranteed under federal law by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. She worried that keeping her son in a private environment might prove detrimental to his ability to learn how to function in the real world. After three years, with some hesitation, she returned him to public school. Since then, he has enjoyed greater stability, and Michelle receives quarterly reports that help her keep tabs on his reading and writing skills. It turned out that a system for the masses was what worked for her son.

Katie Piehl’s mother, Nancy, worked in public schools her entire career. Her life was shaped by a transfer she made as a schoolgirl in Saginaw, Michigan. She grew up on the outskirts of town, with the “farm folk,” and attended a private parochial school until she was fourteen. But when it was time for high school, she attended a racially diverse public school in the city.

At the time, not many kids she knew went to college. Nancy became the first person in her family to pursue higher education, and she studied speech pathology at Western Michigan University, which is public. She met her husband there. It was the early Seventies; he enlisted in the Air Force and managed to avoid Vietnam by getting stationed in Omaha, Nebraska. After three years, the couple had a chance to move. “We picked Phoenix sight unseen, and we went,” Nancy told me. When they arrived, the oleanders were blooming. She plotted out all the city’s school districts on a map so that her husband could take her to drop off job applications at each one. She moved through schools in south Phoenix before landing in the Washington Elementary district, home of Mountain Sky, where she later enrolled Katie and her sister. Nancy’s colleagues elsewhere in Phoenix envied her district’s model for speech therapy: she was supported by a special-education teacher, another full-time speech therapist, and an assistant.

At times, she’d find that her job was misunderstood. “People would always write letters to the editor and say teachers shouldn’t get paid much because they have three months off every summer and spring break and fall break,” she said. She retired in 2007, and by then her school’s speech model had been reduced to just one therapist and two aides — the result, Nancy said, of cost-cutting. “I think people should understand how much of their life a good teacher invests in their school, their kids, and their job. That takes a lot of time, and Katie throws herself into it.” She added, “If I were a teacher, I’d be real disillusioned.”

Before I left Arizona, Katie invited me to her home — a modest first-floor apartment in central Phoenix, surrounded by vine-covered boutiques and trendy coffee shops. She described it as “snooty, kind of,” and explained that the rent was a bit of a stretch. When she began teaching eleven years ago, her salary was $29,000; last year she earned $40,000. With help from her mom, she has become impressively thrifty, and manages to save enough to invest hundreds of dollars every year in her classroom.

We sat at her wooden dining table, which was decorated with a vase of white flowers. Her cats, Henry and James, jumped in and out of our laps. “You have such incredible teachers out there who’re doing so much for their students, and it’s getting harder and harder every year,” she said. I asked her about the latest E.S.A. expansion. “Don’t do more to make it harder on us,” she replied. “Our job is tough enough as it is. It feels like every year we have to do more with less. And this just adds to it.”

She took a sip of water. For her mother, teaching was a way of opting into her community; for Katie, it has become difficult to grasp what her efforts are worth to those she works for. “I don’t think education should always necessarily be a high-paying job, because then you’re going to get the wrong kind of people,” she went on. “But pay should be something that’s not a joke. It feels like a joke when I talk about my salary. Why am I not valued as a professional? I’m good at what I do, and I work hard. I just don’t feel valued much as a member of society.”

Nancy had told me that she couldn’t imagine her daughter doing anything besides teaching. As Katie and I talked, I asked what she thought about leaving her career, or perhaps Arizona. “I feel like I’ve found enough ways to make it doable, but as things continue the way they do over time —” She paused. “I’d like to say no, but at the same time, who knows? I might just get fed up.” ?