Having already determined in Citizens United that corporations are people, the Supreme Court decided in May that people, at least working people of vulnerable status, can be prevented from acting as corporations. In three consolidated cases involving disputed wage claims, the Court ruled that employers can force workers to accept individual arbitration instead of joining together in class-action lawsuits. Writing for the majority, Trump-appointed justice Neil Gorsuch maintained that the 1925 Federal Arbitration Act was more pertinent to the cases at hand than the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, which asserts that workers have a right to “concerted activities”…

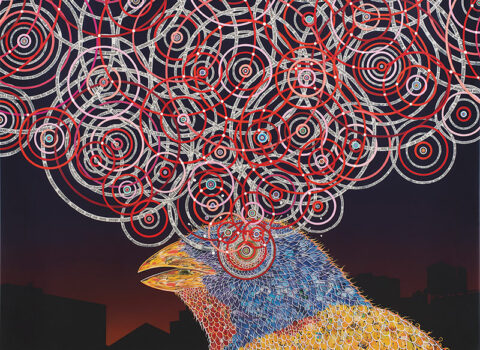

Unions must either demand a place at the table or be part of the meal