America’s Constitution was once celebrated as a radical and successful blueprint for democratic governance, a model for fledgling republics across the world. But decades of political gridlock, electoral corruption, and dysfunction in our system of government have forced scholars, activists, and citizens to question the document’s ability to address the thorniest issues of modern political life.

Does the path out of our current era of stalemate, minority rule, and executive abuse require amending the Constitution? Do we need a new constitutional convention to rewrite the document and update it for the twenty-first century? Should we abolish it entirely?

This spring, Harper’s Magazine invited five lawmakers and scholars to New York University’s law school to consider the constitutional crisis of the twenty-first century. The event was moderated by Rosa Brooks, a law professor at Georgetown and the author of How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales from the Pentagon.

participants

Donna Edwards is a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maryland and cosponsored a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

Mary Anne Franks is a professor at the University of Miami School of Law, president of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative, and the author of The Cult of the Constitution: Our Deadly Devotion to Guns and Free Speech.

David Law is the Sir Y. K. Pao Chair in Public Law at the University of Hong Kong and the editor of the forthcoming Constitutionalism in Context.

Lawrence Lessig is a professor at Harvard Law School and the author of America, Compromised and Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress—and a Plan to Stop It.

Louis Michael Seidman is the Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Constitutional Law at the Georgetown University Law Center and the author of On Constitutional Disobedience.

Photographs by Thomas Allen

“the constitution itself is illegal”

rosa brooks: Let me tell a story about what I do in my constitutional law classes at Georgetown. In the very first session, I say to my students, “The United States has the oldest continually operative written constitution in the world. How do you feel about that?”

And everybody goes into a “rah-rah, Constitution” mode. The U.S.-born students look smug, and the non-U.S.-born students look puzzled. After everybody has a chance to talk about how great it is that the United States has this very, very old written constitution, I ask them how they would feel if their neurosurgeon used the world’s oldest neurosurgery guide, or if NASA used the world’s oldest astronomical chart to plan space-shuttle flights, and they all get quiet.

So I thought I would ask you all to talk about one of the many oddities of American constitutional history. The United States was born of violent revolution, and it was born of a group of people coming to believe that the form of government they were living under was illegitimate, and that they had the right to say, “We don’t like that government anymore.” They came up with an alternative form of government, which was revised still further at the Constitutional Convention, giving us the document we have today.

How did it happen that the United States, which was born in a moment of bloody revolution out of a conviction that every generation had the right to change its form of government, developed a culture that so many years later is weirdly hidebound when it comes to its form of government, reveres this piece of paper as if it had been handed by God out of a burning bush, and treats the Constitution as more or less sacred? Is it really such a good thing to have a document written almost 250 years ago still be viewed as binding us in some way?

louis michael seidman: It’s not just the American Revolution but the Constitution itself that was an act of constitutional disobedience. At the time the Constitution was written, there was another binding document, the Articles of Confederation. It required the approval of every state legislature to amend it. The delegates to the Constitutional Convention arrived with the explicit instruction that they were to propose amendments to the Articles of Confederation.

When they met behind closed doors—with no public input at all—one of the first things they decided was to disregard their instructions and just ditch the Articles. They agreed to have a method of ratification that was different from the one outlined in the Articles. The ratification was not to be done by the state legislatures; it was to be done by constitutional conventions, and it was not to be approved by unanimous consent, which was what the Articles provided, but rather would go into effect when nine of the states agreed.

So, from the beginning, the Constitution was in some sense illegal. It’s a neat trick to get from that to a time when people feel bound to respect the document.

david law: Thomas Jefferson would be rolling over in his grave. He thought that every generation should rewrite the Constitution. It should be revised every nineteen years.

That is actually the average life span of a constitution around the world. The average constitution has about a one in three chance of being revised in any given year. And here we are, bragging about the fact that we’re running Windows 1.0 and we have these nine superannuated people—Supreme Court justices—appointed for life to keep patching it.

This is a little like the inhabitants of a really old apartment building pledging their undying loyalty and allegiance to a blueprint that must never be changed, and so when you want to renovate your bathroom people dig out the blueprint and ask themselves whether the bathroom renovation is in accordance with the spirit of the blueprint.

mary anne franks: We have not, as a country, fully confronted the fraudulent nature of the Constitution and the founding itself. The revolutionary spirit was always, from the very beginning, a limited one. It was a revolution for some people, and this idea that we threw off the yoke of tyranny was immediately constrained by the idea that you didn’t want to throw it off too much. The founders didn’t want to throw it off for slaves, and they didn’t want to throw it off for women. They wanted to have this very contained revolution.

This tension has persisted and has haunted us. The mythology is that there is this grand moment of revolution, when we decide that we stand for equality and justice and all the rest of it. But we also know that the mythology includes all these asterisks, because the people who made all those decisions were the most privileged members of society, and even though they sought, for themselves, not to be oppressed and not to be exploited, they immediately denied that right to everybody else.

Sometimes we say, “Well, they were men of their time,” and there is an interesting tension between this idealized view of the Founding Fathers as almost divine figures and at the same time ones who couldn’t possibly have understood that slavery was wrong, or taken a real stance against it, or declared that women were equal human beings to men. We act as though those would have been crazy ideas.

There were people, of course, Abigail Adams maybe most famously, who pointed all this out at the time, both about slavery and about the tyranny of husbands over wives. She even used the term “tyrannical.”

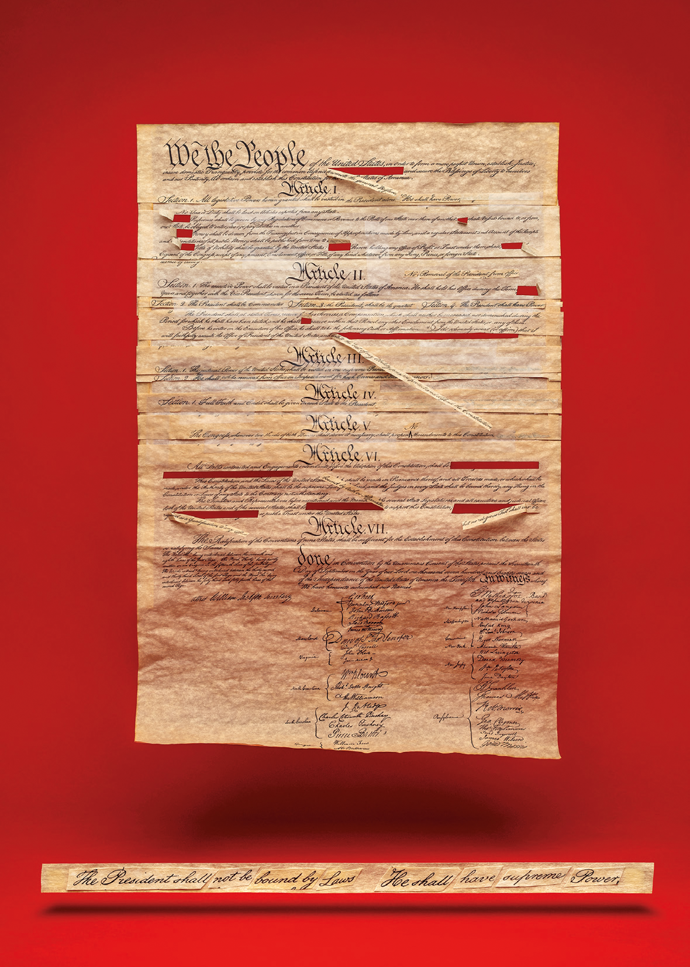

That is really the structural, psychological, and sociological problem we’re dealing with: we have lived with this mythology for so long, and we don’t quite experience the cognitive dissonance that it ought to generate within us, because every word of the Constitution—starting from this premise of “we the people”—is a lie.

lawrence lessig: There is a huge gap between the kind of democracy people want and the kind the Constitution and our political culture currently allow for.

One of the reasons for that gap is that we liberals have spent the past fifty years saying, “The way we should be tinkering and changing our Constitution is by getting lawyers before the Supreme Court who get nine justices to vote in the way we want them to vote.”

donna edwards: An obsession with appointing Supreme Court justices is what happens in an environment where the three branches of government are out of whack. The Executive has too much power; the Congress is sitting stalled for a whole host of systemic reasons; and the courts have been deeply politicized.

When those structures are out of whack, then it forces us legislators to cherry-pick the passages from the Constitution that work for us, because we know that the institution that’s supposed to uphold them isn’t functioning. Legislators can only hope a court will bypass all this other dysfunction in the other branches.

lessig: When there have been constitutional, grassroots movements, movements that have tried to say, “We should be involved in making our Constitution reflect us,” there have been organized efforts, on the left especially, to say, “Shut up. Get out. This is not for you; it’s for the experts. It would be disastrous if the people got close to touching their own Constitution! It would be chaos.”

So I think one of the really important questions is: Do you expect people to rally around a document that has no connection to the democracy of today, or yesterday, or even forty years ago? When was the last time we had a political movement that manifested itself in a change in the Constitution that allowed us to say, “This is ours; this is our part”?

“we have a president who treats the constitution like a dirty limerick”

brooks: In the context of the Trump presidency, there is a renewed interest among ordinary Americans and journalists in the Constitution. I am constantly being asked by non-lawyer friends, “Are we in a constitutional crisis?” Or, “Is it unconstitutional for Donald Trump to declare a national emergency to get funding to build a border wall?”

I’m always a little torn about how to answer. You could perhaps make an argument that it’s perfectly constitutional for Trump to declare a national emergency and build a border wall or ignore the courts and add a citizenship question to the census. But part of my lawyer brain wants to say, “Well, what do you mean by ‘constitutional crisis?’ ” And another part of me wants to say, “Those are irrelevant, stupid questions.” I don’t really care whether or not it’s constitutional.

Why would that change anything for anyone? If we think something is evil and a bad idea, then it’s evil and a bad idea without regard to whether or not it is constitutional. Why should that have any relevance to a set of policy questions and moral questions that the United States is facing now?

edwards: I’ve stopped saying about Trump that we’re in a constitutional crisis. I think there was a time when I uttered those words often. And they became meaningless: every crisis is judged to be one that is constitutional.

I think part of the reason that today feels like a crisis is because the legislative branch is not functioning. When you have a legislature that isn’t doing its job, and the president is acting beyond his authority, and you have no check on that—you may be in a crisis.

And maybe it’s because I come out of the legislative branch, but it pains me to see Congress in such inertia that it gets in the way of us trying to at least preserve the elements and spirit of a Constitution that I think does bind people to a set of shared ideals, whether or not they know the details. I’d like to figure out how to restore that balance.

franks: There was an extraordinary moment in early 2017 when Trump announced his “Muslim ban” and you had this wonderful visual of all these lawyers descending on airports and actually saving us, or it looked as though there was this remarkable moment for lawyers in this country, and I’ve never felt so proud to be part of the profession.

But perhaps that was a mirage, and, I agree, there’s a constant tension between whether you can try to dismantle a bad practice from the inside or if you have to blow up the whole thing and start over. Do we need to go William Lloyd Garrison on the Constitution1 and just start over?

The position that I’ve taken as a preliminary step is to think, “Well, is there anything in the Constitution that is meaningful here, in a larger sense?” And for me I think the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause is where a lot of our efforts might be focused and energies spent.

The way politicians and legislators interpret and use the Constitution today is like taking a scripture and using all the parts that validate the way they want to see the world and ignoring everything else. Because if we took the Constitution seriously as a whole, then we could have a lot of interesting discussions.

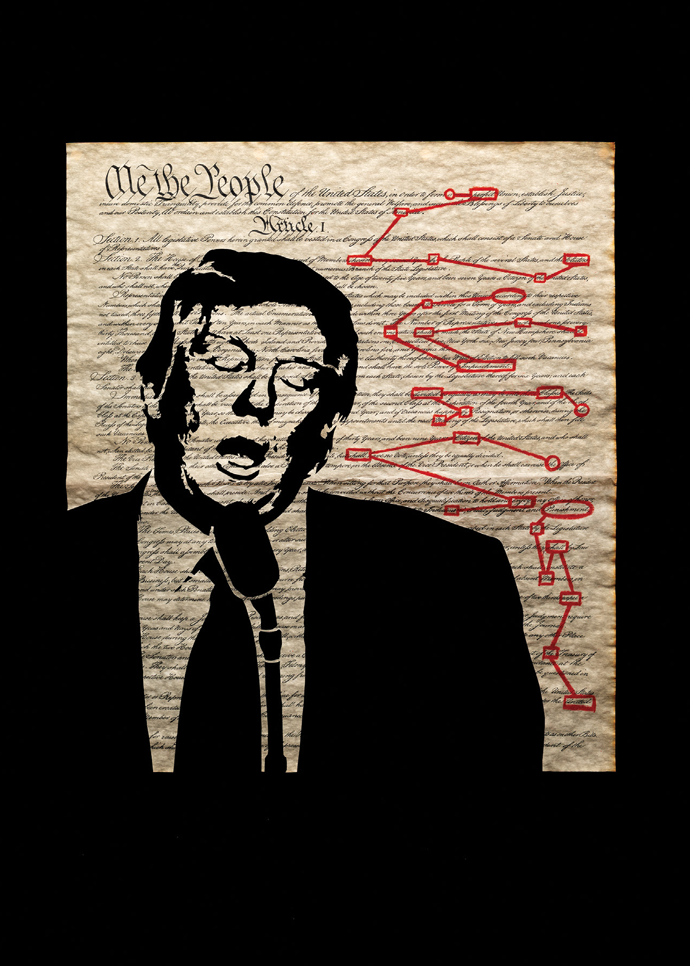

So arguments about Trump, just to take one example, end up having nothing to do with constitutional fidelity; we’re dealing instead with constitutional selectivity, and that is one of the biggest problems we face. We’re ignoring the fact that there are real complexities to taking the document as a whole, and we should not be able to cherry-pick passages.

There’s that deceitful—hypocritical maybe—sense of, “I’m arguing on behalf of the Constitution,” when that’s not at all what you’re arguing. You’re arguing on behalf of one piece of the Constitution, and your particular interpretation.

It always makes me think of my upbringing as a Southern Baptist. In church we were told, “Here is how we know that homosexuality is wrong, because of this passage in the Bible.” And that was the only part of the Bible that we seemed to be taking seriously that day. It’s that same sense of fervor to say, “I took this one passage, and I’m telling you it’s the most important passage, and here is the only way that you can read it, and anyone else who disagrees with me isn’t just wrong but spiritually wrong, and spiritually broken, and doesn’t understand the underlying text.”

That’s the kind of pathology I think we’ve developed around the Constitution, and that is why it is toxic and unhelpful for so many of our important political discussions today.

seidman: Maybe the right way to think about the Constitution is not as a legal document at all, not as a lease or a will or something like that. Instead, think of it as poetry. As a poem, or symphony. And if you think about it that way, it can be a symbol that unites the country. So everybody is in favor of providing for the common defense and the general welfare. Everybody is in favor of equality and liberty. That’s what the Constitution stands for.

Now, nobody would say that you have an obligation to obey a poem or a symphony; you can be inspired by it. It’s not like it’s meaningless. It causes us to have certain emotions, but you don’t obey a poem. And poetry doesn’t settle arguments. We can all be inspired by the same poem and reach different conclusions about what we ought to do.

I think the problem with the Constitution is not its status as a national symbol that unites us; it’s when people try to use it to settle arguments and when they get into the nitty-gritty of the Constitution that it doesn’t sound like poetry at all. Things like the fact that you have to be a natural-born citizen to be president of the United States, or that every state gets two senators.

That’s where we get into trouble, and that’s where constitutional obedience is really problematic. But as a national symbol, as poetry, I’m all for it.

lessig: But the problem is that we have a president who treats it like a poem, or a dirty limerick—he treats it like something he doesn’t have to respect or follow, and I don’t think that’s a good idea.

seidman: The very last way we want to confront Trump is with the Constitution as a legal text. That is a way of turning this argument over to lawyers, to people with technical expertise, who are elites, who are arguing about things like, “Gee whiz, what is the exact meaning of the word ‘emolument’ in the eighteenth century, and how does it relate to foreign powers?” and a lot of stuff that is beside the point when it comes to Trump.

The American people have to be persuaded that Trump is bad for the country, that he doesn’t represent the kind of country that we want to live in. Yes, it’s going to be harder to do that because there are institutional structures that get in the way, but it’s not impossible.

The Democrats won a huge victory in the House last year. There is no reason why they can’t build on that and elect a different president, a different Congress next year. But the way to do that is not by telling people, “Whatever you think, you have to believe certain things because they’re in the Constitution.” People don’t like to be told they have to do things. The way to do it in the end is to persuade them.

On some level, it’s just fundamentally autocratic to say, “I don’t have to explain to you why Trump is bad. I don’t have to persuade you; it’s just that the Constitution says he’s not allowed to do this.” In a well-functioning democracy in a real republic, things are changed because people are persuaded, not because they’re told what to do by elites, especially by elite lawyers.

In the end, the problem with Donald Trump is not that he’s violating some technical legal provision in the Constitution; it’s that he’s writing bad poetry.

lessig: There is no “the problem” with Trump.

There are many problems with Trump. And one of the problems is that he is violating the core anticorruption principle inside our Constitution as it’s supposed to constrain him.

I am happy to have one hundred lawyers go and try to take that on, but that doesn’t address the larger problem, which is, “How do we bring the Constitution to a place where people feel like it’s theirs again?” And the only way we get there is to imagine a process for changing it.

“constitutional creep”

brooks: We all know that passing amendments through our polarized Congress is nearly impossible because of the fact that you need a two-thirds majority vote in both the House and the Senate—as such, that would seem to leave the courts as the logical place for legislative activism, right? It seems today that that’s where almost all political energies are devoted.

edwards: I can recall a time before I was involved in electoral politics, when I was a young lawyer and I worked with a lot of groups, and all of them were proposing different constitutional amendments. And then we’d go to people to try to fund them, and everyone would say, “Oh, no, we can’t do that, because what if we opened up the entire process, and then anarchy would rule?” Or, “Those other guys we don’t like will then start to make some changes that we don’t want.”

Then I got into Congress, and lo and behold, Citizens United was decided and I did . . . what? I proposed a constitutional amendment.

I had been discouraged as a legislator—a relatively new legislator—from introducing anything that looked like a constitutional amendment. That was the kind of thing Republicans did, but Democrats did not propose amending the Constitution. But I went forward anyway.

It took several years from almost no one signing on to every single Democrat being in favor of an amendment to deal with the problem of money in politics. And I don’t think that was a sea change brought about by legislators. It was a sea change that was brought about by people in communities who were tired of the system. There is a willingness on the part of the people to change the Constitution for the better, to bring it more in line with democratic principles.

law: In politics, as in the rest of life, everyone wants to escalate the dispute. “I want to speak to your manager.” “I’m going to make this into a constitutional litigation.” Right? And so they’ll go to the courts, and they’ll make it a constitutional argument—and I would call this constitutional creep. Political scientists talk about the judicialization of politics, or the constitutionalization of politics, where things get pushed into the constitutional arena, things are turned into constitutional arguments. Debates or issues that could, or maybe even should, be solved in lots of other ways, via other political mechanisms, instead become arguments about legal doctrine.

And the terrible thing is, the more paralyzed political institutions are, the more likely we are to shift all these questions into the judicial and constitutional forum. So we’re really stuck. On the one hand, we can’t change the document because of the paralysis of electoral politics; on the other hand, we also have more and more issues being pushed into the judicial arena, into the constitutional arena, precisely because of that paralysis.

I see Americans trapped within a box, unable to transcend the constitutionalist way of thinking. Countries actually don’t need written constitutions. The United Kingdom doesn’t really have a constitution. New Zealand doesn’t have a constitution. In a functioning democracy, you don’t need one.

To be honest, I think America might be better off as a monarchy. In Canada, you have a symbolic king or queen—a nonpartisan head of state onto whom people can attach their loyalties—alongside elected leaders, who actually do the hard work, and then you can criticize the government and the constitution without appearing to be disloyal or a bad citizen. And we don’t have that. In America, people declare their loyalty to this ancient document instead.

brooks: But the political situation in countries without constitutions is a disaster, too, isn’t it?

law: New Zealand is working out just fine. The United Kingdom is just fine. They’re not worse off than we are, are they? No one is running riot in the streets of Auckland or London. There is this preliminary question that we generally don’t grapple with in this country, which is, “When and why do people actually need constitutions?”

And there is actually a limited range of situations in which constitutions are doing a lot of work, and I’d argue that there is a limited range of situations in which constitutional courts are doing a lot of work. There are well-established ways of doing things. If everyone understands, for example, you have to have elections for parliament every four or five years or so, that doesn’t need to be written down or enforced by the courts. It just happens.

If you’re in a revolutionary moment and you need to decide on a new set of arrangements, which is where we were in the late eighteenth century, then okay. A constitution is helpful. But if all we’re going to do is keep chugging along, we can be like the New Zealanders. We can be like the Belgians, and basically not have a functioning constitution, and things just keep working. If we want to change, ironically, that’s when people probably most need a constitution.

seidman: I disagree—I don’t think we need the Constitution even in times of change. We need to forget about constitutionalism entirely. Or at least forget about the constitutionalism of rules and detail—of arguing over what exactly the framers meant in this or that passage.

There is a subterranean but nonetheless robust and long-standing tradition in this country of constitutional disobedience. Some of the greatest figures in our country’s history and some of the country’s really important events have involved a refusal to take the Constitution as binding on all of us. Thomas Jefferson thought the Louisiana Purchase was unconstitutional but he went ahead with it anyway. Abraham Lincoln said repeatedly that the Constitution did not permit the federal government to free the slaves.

What keeps the country together, in the end, isn’t the Constitution. It is a bunch of sub-constitutional or extra-constitutional norms about behavior, things like “you don’t default on the national debt,” or “you don’t say we’re just going to block any Supreme Court justice who is nominated.”

Those are the things that keep the country together, and that’s what we have to work on. And that’s just very different from paying a lot of attention to constitutional detail.

lessig: I feel like we’re a little in the clouds. It’s fine and good to look comparatively and say some people do well without constitutions. Some people have constitutions.

But we have a constitution right now. And if the United States Congress passed a law that said corporations can’t give money to independent political-action committees, the Supreme Court would say, “No, that law is unconstitutional.” And if somebody tried to enforce it against that corporation, that person would be violating the law.

The Constitution is not producing a democracy that’s responsive to the people. And that is a gap that we have to find a way to fix. It’s one thing to say we can fix it by just imagining our norms to be in the right place, but I think a lot of people have been imagining norms and not getting very far.

mary anne franks: As a moral matter, as a legal matter, as a constitutional matter, I think the only principle that’s actually universally defensible is the principle of reciprocity. The only thing that keeps us from immorality, the only thing that keeps us from illegality is the concept that whatever it is that we choose for ourselves, constitutionally or otherwise, we have to choose for everyone.

We don’t get to say, “I get a First Amendment right, but you do not.” We don’t get to say, “I get Second Amendment rights, but Philando Castile does not.”2 We can’t do that.

If we say that you have the right to, for instance, defame or harass somebody online and that forces them to stop talking and they can no longer express themselves for fear of that harassment—those death threats, or people hounding them out of their home—why don’t we have a conversation about First Amendment rights on both sides?

As I mentioned, the Fourteenth Amendment says there has to be equal protection under the law. If we started there as an ethical matter, a constitutional-cultural matter, where would that get us? If we could have that conversation as opposed to these extremely selective, highly dubious claims that are made on the part of the most privileged members of society about how their rights are under attack when of course this is false, then what would be possible?

What we get instead is a piecemeal focus on First Amendment issues, Second Amendment issues, Fourth Amendment issues—the rights to free speech, to bear arms, and not to suffer unjust searches and seizures, respectively. And the Citizens United case is an example of that. This becomes a free-speech issue as opposed to whatever other kind of interesting conversation it could be, and the First Amendment is used to shut down conversations instead of begin them.

lessig: I think what we have to focus on in a very precise way is: What are the steps that could get us to a place that could make the democracy a responsive democracy? How do we break this deeply unrepresentative system that we have right now?

The U.S. Constitution has the provision in Article V to allow us to call a convention to propose amendments. If two-thirds of the state legislatures vote to convene it, the Constitution requires it. That’s what we need to do.

edwards: I’m a little leery about opening up the whole show in a constitutional convention, but I think it’s worth thinking through how something like that might be done in a way that doesn’t allow for monkey business, especially from conservatives.

I don’t think the current political process really positions us to work through these constitutional challenges.

seidman: I don’t think we need another constitutional convention. You know what would happen? The country would come apart at the seams. And the reason it would come apart at the seams is because if we really confronted the things that divide us, and really were honest about them, there would be no reconciliation.

To start with, there would be a huge fight about whether the United States is a Christian country. And if we confronted that, God knows what would happen. It’s a little like a marriage—there are perfectly successful marriages that go on for years and years in which the spouses are happy, and the reason they’re happy is precisely because they never actually sit down and have a deep conversation about what the purpose of the marriage is.

lessig: I don’t think people are happy. We’re not talking about happy people. We’re talking about people who are not happy. That’s the point. We’re starting at a place where it’s not working.

seidman: But they’d be less happy. What keeps the United States together in the end is not some deep agreement about the philosophical issues that would surface if we really tried to rewrite the Constitution.

What keeps the country together—to the extent it is still together—is a much looser sense that we’re all in this together, that we sink or swim together, and some very loose ideas about tolerance and equality. If you try to put that into a legal text, things are going to come apart at the seams.

lessig: But, Mike, this is a false dichotomy. You’re saying we couldn’t possibly have a convention that would rewrite the whole of the Constitution and our foundations as a country. I agree with that. Of course we can’t.

What I’m talking about is the fact that we have a constitution right now that creates a deeply corrupted process for selecting our representatives and our president, and we have no way to fix that, given the current way that the Constitution itself gets amended.

So this is not about agreeing on fundamental values; it’s about the smaller point of, “How do we get to a democracy that people actually feel represents them?” And that will only happen if we have some fundamental changes to the constitutional order, which we won’t get unless we figure out a way to amend the Constitution.

edwards: I think our system—and especially our elected leaders—are averse to change. But there is still a revolutionary spirit within the American public that doesn’t exist among elected leaders. People still want to tweak and change and reimagine the Constitution; they just don’t feel as though they have any way to do so. But maybe they do—they just don’t realize it.