Fear is an old emotion, laid down deep in the nervous system. Without its promptings no species of animal life could have survived and civilization could not have developed. Certainly we could not live among our thermostats and wirings and crowded highways without it. Nevertheless it has always been a real problem for man. For the animals it seems to serve a purely beneficent purpose. They only know the instinctive urge to escape an enemy that their senses warn is in the immediate vicinity. Men, however, are afraid not only of specific enemies, but of death in the abstract. They have to be afraid not only of certain malignant organisms like typhoid germs, but also of the concept of ill health.

These fears are part of the tribute we pay to our humanity. We have always had them and we always shall. In our efforts to deal with them we have developed religion, science, and many of our most valuable social institutions. Tempered with reason and faced with an amount of fortitude not beyond the reach of most people, such fears have been tolerable, though of course unpleasant. But the apprehension with which so many Americans are now regarding the world is a different thing, an emotional state where every fresh headline increases their sense of impending disaster.

A perfect flood of books and articles are appearing on the topic of “saving our democracy.” Writers and speakers are analyzing with almost morbid thoroughness every weak timber in our social and economic structures. In the so-called quality magazines and the best radio forums the note is as strong as among the newspaper columnists. Ministers and educators dwell on the theme with passionate anxiety. These are not politicians intent on cleaning out the rascals of the other party, but the makers of our public opinion. Our intellectuals are as jittery as anyone else. The very word “jitters,” which is on everybody’s tongue, is a product of the 1930s. It means a racking fear that shakes its victim out of poise and nervous integration.

Fear is infectious. Children catch it from their parents, and acquaintances from one another. When it is in the air, as it is now, it can become almost a mass hysteria, an instrument for any demagogue or any unexpected event to play upon.

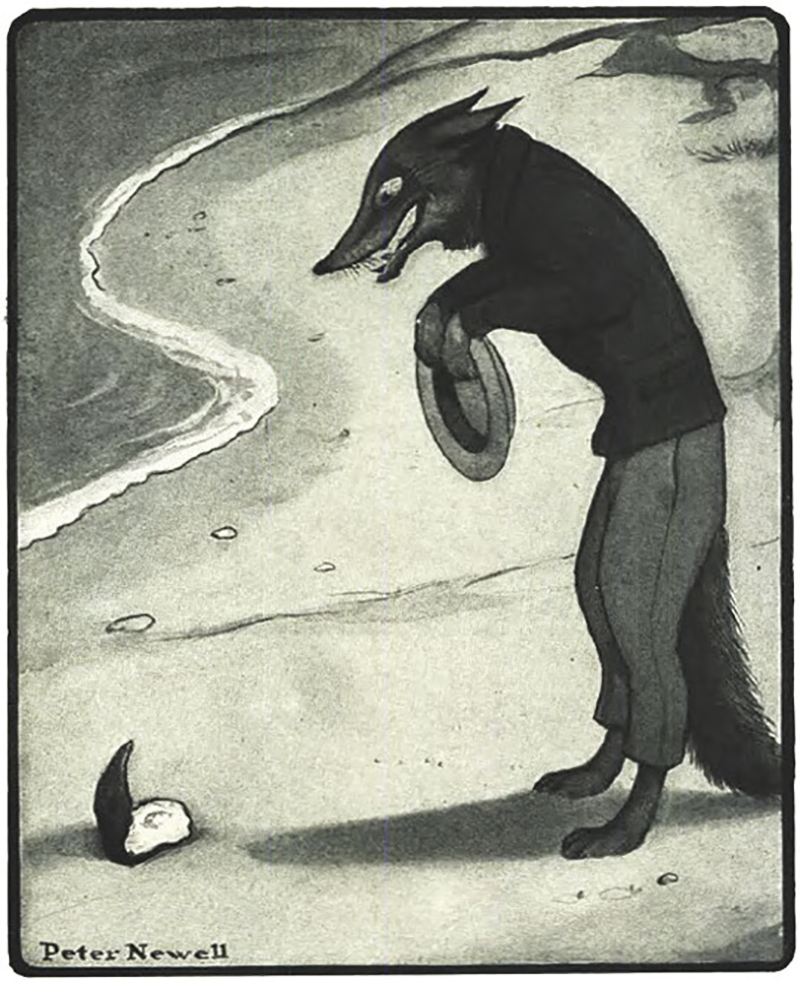

An illustration by Peter Newell, which appeared in the January 1905 issue of Harper’s Magazine

If we may believe the almost universal testimony of physicians, people usually face death with a good deal of fortitude when they finally know it is coming. But the thought that perhaps this pain or this rise in blood pressure may be the first warning signal of some disease that may mean death often sends them into a devastating terror, which completely saps their ability to live normally. The fear of unemployment or bankruptcy is in some respects analogous. It is during the weeks and months when one is facing the possibility and thinking, “How can I ever endure it?” and “How will my family exist?” that the suffering is most cruel. There was never a time when so many people were in this kind of torment over such an extended period.

These fears are bad enough in themselves, but in the new world of flashing communications, we have to be aware of every incident, which piles up international tension. The impact of a fearful world is upon us all the time. We cannot escape it except in sleep—and sometimes not then.

Psychiatrists know a great deal about the mechanism of anxiety and how to relieve it in its classic forms, but their literature has scarcely begun to deal with the brooding mass anxiety and individual insulation against it. Ministers become skillful in helping people face death, but most of them have not yet faced this need. Religion, the spring from which fortitude has long flowed, is also in a difficult moment, because its traditional vocabulary has lost its meaning for many of us and is only at the beginning of a process of restatement. One approaches the subject hesitantly and humbly.

From “Courage for To-morrow,” which appeared in the April 1939 issue of Harper’s Magazine.