This Is Not a Test

Illustrations by Matt Rota

Nobody in their wildest dreams would have ever thought that we’d need tens of thousands of ventilators.

—President Donald Trump

It is late February, three weeks before the end of the world, and I’m lying entombed beneath nearly sixteen tons of rubble. Three hours have passed like this, with me semiconscious and unable to speak, limb-tangled in the remains of this charred and decimated building. All afternoon I have been waiting for the movieland shouts of heroic first responders. I have been waiting for the inquisitive sniff of search-and-rescue dogs. I’ve been waiting for someone to staunch my wounds, to call my loved ones, to tell me, through the crack in the rubble, to hold on, that everything will be all right. But instead there’s only been this: the indifferent roar of a plane overhead, and the distant ebullience of birdsong.

Out of nowhere I hear the hard crunch of gravel, the footfalls of a heavy person. “Hey, Barrett,” the voice says. “This is one of the Observer Controllers. Real World: How you holding up? You doing okay?”

Real World. This weekend, I’ve been scrutinizing that phrase with a kind of stoner-ish intensity. In the real world, it’s a sun-drenched morning in late winter, and however many miles from where I’m lying, there’s a pandemic brewing in Wuhan, China, the scope of which none of us yet understand—not even those of us here in Disaster City, a fifty-two-acre training compound for search-and-rescue teams that’s been designed to anticipate every last possible disaster. Located in College Station, Texas, the facility was founded in 1997 and is the brainchild of a Texas A&M professor named Kem Bennett. After the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, Bennett wondered if his university could create a “mock community,” one that would allow first responders to engage in “realistic, hands-on training.” Ever since, the compound has served as a gauntlet of woe, a place where, as its website states, “tragedy and training meet” and “anything is possible.”

Many of FEMA’s search-and-rescue workers now train in Disaster City, and since 1998 the property has been a member of the National Domestic Preparedness Consortium, a group of training centers overseen by the Department of Homeland Security. It is part of a system that is supposed to prepare us for all eventualities, from hurricanes to electrical fires, from nuclear strikes to global pandemics. Disaster City makes a difference, its website claims, by “recognizing and preparing for the unique challenges and opportunities the future holds.”

This weekend’s simulation is something that happens every year, an Operational Readiness Exercise, this one involving a hazmat drill. Two hundred first responders are participating, and I am serving as one of more than a hundred Living Victims—people willing to get bedecked in prosthetic gore and bloody makeup, only to subject themselves to a whole catalogue of misfortune. The coup de grâce of today’s exercise is what I’m doing right now, the Rubble Entombment, which has been going on for the past few hours and which, I must confess, has started to make me sweat.

“Barrett! Real World: Talk to me. You in there?”

If this were the Real World, there’s no doubt that I’d be severely dehydrated. No doubt that I’d be mewling from shock. But instead I’ve been reading Jean Baudrillard on my phone, and for the time being, anyway, haven’t lost all sense of reason. This is why when the Observer Controller leans down and asks again if I’m all right, I clear my throat and, in a loud, clear voice, tell him that I’m fine.

Spending a weekend inside a disaster simulation might not be most people’s idea of leisure, but I have to admit I’ve been drawn to such exercises for about as long as I can remember. During the bright summer days of my suburban childhood, I invariably attended my local police department’s annual “Safety Town” seminars. There, school-age children would learn best practices for gun and motor-vehicle safety, gas and electrical precautions, and strategies for how we could protect ourselves whenever our parents left the house. It was an event at which I served with great distinction as our sheriff’s deputy volunteer assistant. And I confess that in the third grade, while the other kids played at recess, I would often stay inside and disturb my teacher by doing elaborate schematic drawings of my school’s floor plans, using a color-coded system of arrows and asterisks to highlight, in the event of a tornado or fire, the most expeditious routes of egress. It was this recess activity in particular that caused the school administration to call home to ask my mom whether everything was okay and to maybe get a better sense of just what exactly was bothering this kid.

In the contemporary imagination, obsessive-compulsive disorder exists as a quaint neurotic condition, a quirk of handwashing and drawer organizing on the order of, say, Bill Murray in What About Bob? or Jack Nicholson in As Good As It Gets. As someone who suffered from this grim headstorm for twenty years, I cannot tell you how offended I get by these daffy caricatures and how far afield they are from the actual torments of the condition. Take for example a much-cited case study in the OCD literature, about a Brazilian man who became so unduly fixated on the shape of his eye sockets that he constantly prodded their contours, doing this with such frequency and force that he ended up blinding himself.

The average person has thousands of thoughts a day, and for the obsessive-compulsive, most of these are given over to extremely irrational fears, usually of a harebrained “what if” variety. What if I drive my car over the side of this bridge? What if I swan-dive off the ledge at this swanky rooftop party? What if this store-bought aspirin has been surreptitiously laced with cyanide? Most of us experience these unhappy musings but can dismiss them as unreasonable and therefore impertinent. The obsessive-compulsive gets caught up in them and will go to extreme lengths to mitigate their voltage.

For my part, I had developed a morbid fear of disasters, owing to a formative encounter with the 1996 movie Twister, starring Helen Hunt and Bill Paxton. Upon leaving the theater, I became a preadolescent scholar of wind patterns and cloud formations. On rainy days, my thoughts were downright actuarial, and most of my compulsions took the form of prayer. Kneeling on my bedroom’s austere brown carpet, I whispered a fearful apostrophe to God, dozens if not hundreds of times, its lengthy appeals and divine bargainings taking more than twenty-five minutes to recite. I also washed my hands obsessively, using a bitter admixture of bar soap and Clorox bleach, which left my skin hurt and abraded, and turned the surface of my palms a weird, bad-candy pink. On particularly bleak days, weather-wise, I was not above covertly grabbing my parents’ cordless phone and skulking into my bedroom, where I would proceed to call the National Weather Service hotline and ask the operator, in worried tones, whether there were any tornadoes in the forecast for my hometown in southeastern Wisconsin. I called the hotline with such regularity that the otherwise genial operators began to recognize the prepubescent timbre of my voice, and would either ask to speak to my parents or assure me that Wisconsin was not at risk—and please, honey, do not call us again.

When it comes to OCD, one of the more harmful responses that loved ones can have is something called “family accommodation.” This is where, rather than ferrying the individual to the appropriate mental health services, the parents and siblings of the obsessive-compulsive get conscripted into the person’s rituals, no matter their frequency or silliness. On stormy days, I would corral my entire family into our unfinished basement, carrying a flashlight and a transistor radio, plus an assortment of snacks, and ask that everyone stay hunkered down there with me until the rain had passed. Only my older brother opted out of this accommodation, instead adopting what the relevant literature calls “hostile noncompliance.” He huffed petulantly anytime my parents forced him to join us in the basement, openly declaiming that it was “bullshit” and that I was being “ridiculous.” And true though his psychological appraisals may have been, they weren’t exactly therapeutically helpful at the time, nor were the cruel nicknames he’d given me, including “Tornado Boy” and “The Twister Kid.”

Let’s not spend any more time on this. Suffice it to say that as I entered adulthood, my obsessive thoughts took on a more political register. In some sense, this was to be expected. History shows that expressions of OCD dovetail rather neatly with outflashings of social panic, as evidenced by “syphilis phobia” in the 1920s or “AIDS phobia” in the 1980s, when new facts about these phenomena were just coming into public consciousness. Shortly after Trump was elected, I found myself stockpiling dry goods and water jugs in the storage closet of my basement, along with a go-bag, iodine tablets, and more than a couple of first-aid kits. Things reached a high point with the early reports of the novel coronavirus, when I began exercising such extreme measures of sterility that my university students could do nothing but furrow their brows and tap their temples whenever I entered the lecture hall, since my pre-class routine was to immediately start Cloroxing the surfaces.

Around the same time, Disaster City issued a request for “Victim Volunteers,” people willing to don costumes and lie in rubble in order to give the nation’s first responders some vivid, lifelike training. The facility’s social-media accounts showed images of grinning participants, their faces speckled with gore, with captions like “Family Fun Under a Few Tons of Rubble” or “I haven’t enjoyed myself this much in years!” Soon I was on the phone with Merribeth Kahlich, the head of communications for Texas A&M Task Force 1, the state’s FEMA response team and one of Disaster City’s institutional affiliates. “So,” she said, “I understand you want to embed and get a sense of what it’s like to be in a Compromised Victim Situation?”

Even though this phrase sent a bolt of hot dread through me, I told her that I wanted the full treatment, to help out “in any way I can.” “Now, sweetie,” she said, “let me ask you a question: Do you have your own hard hat?” Perhaps you’ll balk at the blasé way that Merribeth just assumed the average American might have this. But of course I do have my own hard hat. (Most emergency-preparedness guides advise individuals to procure protective headwear, particularly if they live in disaster-prone areas.) I didn’t tell Merribeth this, though, because I worried that any overeagerness on my part might have revealed me to be a neurotic half-wit (which in fact I am) and underscored the extent to which my trip to Disaster City wasn’t entirely journalistic. “Well,” Merribeth said, upon finalizing my travel arrangements, “you should be all set.” Then, when I asked about the Rubble Entombment, she offered me a warning. “Honey, sometimes there’s just enough room for you in there. So if you’re the least bit claustrophobic, I suggest that you start getting that mind of yours right.”

I arrive at Disaster City at dawn, under vast Lone Star skies. The Victim Volunteers have been asked to report to Building 119 for orientation and check-in, and during my walk from the parking lot, the campus lies in unrevealing darkness, so I can’t quite see what the day has in store.

After several minutes of compulsive tapping and self-exhortation, I finally summon the courage to enter the building, which is bustling with activity. The two Victim Volunteer Coordinators, Nyssa and LaNell, are busy greeting new arrivals, who are required to fill out lengthy liability waivers. The volunteers who’ve already signed away their rights have lined up beside long folding tables, where there are plastic tubs of provisions—hard hats and leather gloves, flashlights and protective glasses. I quickly discern that Nyssa and LaNell control my placement in the rubble pile, so I start conjuring ways of asking them to position me in one of its less harrowing sectors. But any hope of a cozy arrangement is swiftly upended, because it turns out that Merribeth has already signed me up for the “full entombment.” Or as one of the other coordinators puts it, “Yeah, I believe he’s doing all the nasty stuff. He’s that guy.” (Incidentally, a camera crew for the BBC was also present that weekend, and whenever I saw them around campus, we seemed to regard each other with open animus, like coaches from opposing teams. Later, however, I found out that these Brits weren’t actually participating in the exercise—the cowards—and I confess to feeling a weird but thoroughgoing American pride about this.)

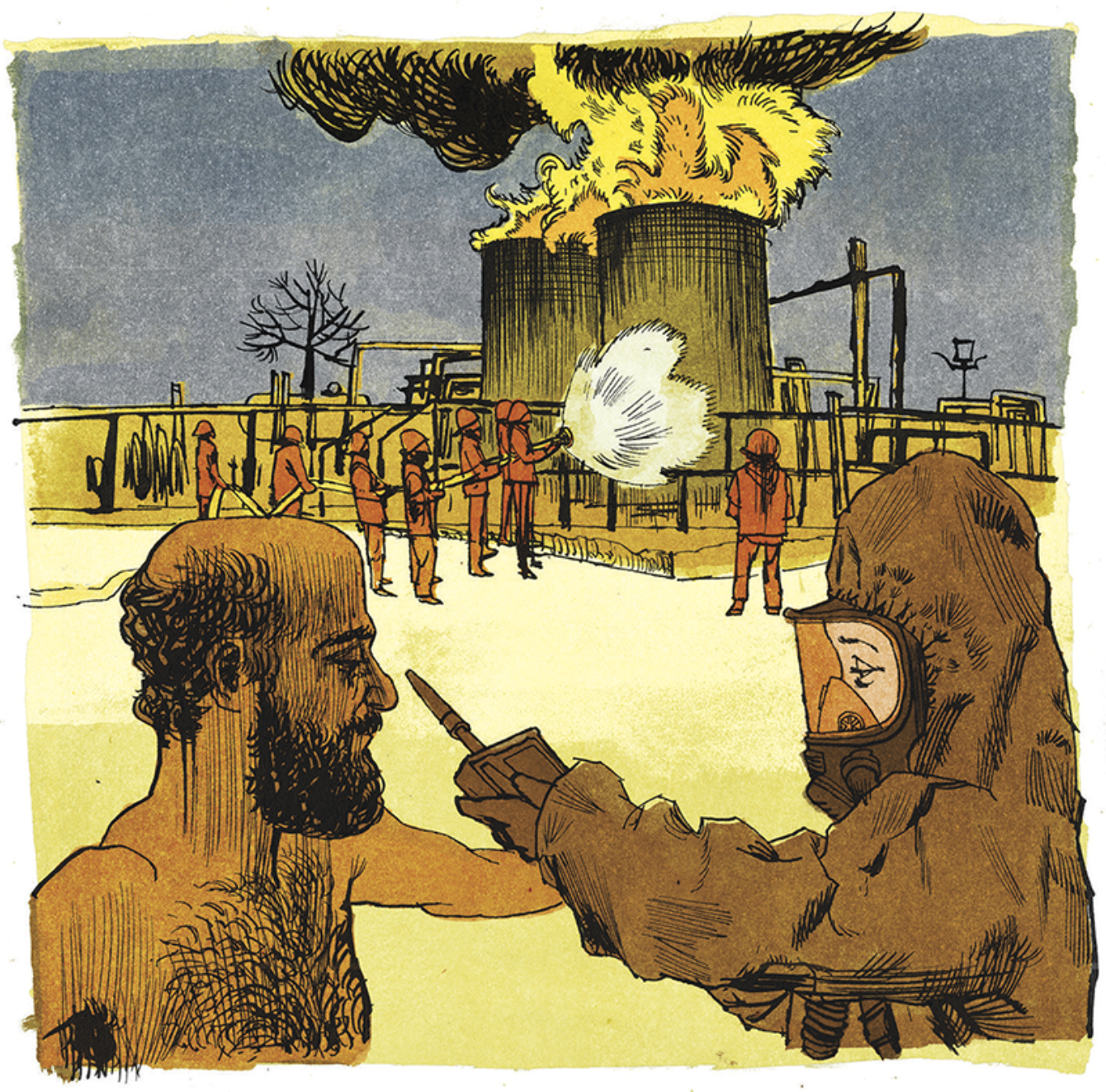

Soon the Victim Volunteers are welcomed and thanked, since our presence is necessary for “the realism of today’s simulation.” This introduction is offered by one of the Observer Controllers, members of the task force who will be patrolling the grounds throughout the exercise and assessing their colleagues’ efficiency in executing their deployments. He then invites us to imagine that we’re residents of a place called “Disaster City, Louisiana,” a small town in “Brayton Parish” with a population of 3,500. Apparently, our largest employer, ChemCo, has experienced a massive pipeline explosion, the seismic force of which has destroyed its manufacturing plant and compromised the structural integrity of several nearby residences.

In order to faithfully reenact the typical chronology of this sort of event, local EMTs and other first responders will start by conducting what’s called a Hasty Search, during which they will corral and decontaminate the exposed area’s Walking Wounded. Sometime later this morning, Texas A&M Task Force 1 and Texas A&M Task Force 2 will assist local authorities in rescue operations, and will be given rear-echelon support from an auxiliary unit of the Texas National Guard, which would likely be deployed by the governor for an event of this magnitude. The National Guard will be bringing with them something called a Wet Decontamination Trailer, which sounds to me like some sort of medieval torture implement. Once the Hot Zones are cleared of the Walking Wounded, the task force will perform live rescues in the collapsed buildings. So the three acts of today’s simulation will be: Walking Wounded, Decontamination Bath, Rubble Entombment. “We will be rescuing throughout the day and night,” the Observer Controller says, “and we’ll probably stop sometime around ten o’clock.”

LaNell then explains that many of us will be placed in very deep, dark spaces and that our cell phones probably won’t have service, so we should get “prepared for that.”

“Don’t think ‘I’m gonna be fine,’ ” LaNell says, “because it’s very cold under the concrete, so take the mats and take the sleeping bags. We don’t want you to become a true victim.”

“Because we did have some of those last year,” Nyssa adds.

Her warning prompts some of the Victim Volunteers who attended last year’s event to tell us newbies about one person who’d been left in the rubble pile for seven hours, and another person who, after she’d been exhumed, pale and in need of fluids (I’m guessing), was discovered to have a mild case of hypothermia, which meant that the task force had to call a medic.

This raises a question about my fellow Victim Volunteers, which is, what would possess people to willingly endure coffinlike enclosures without any kind of assurance that they’ll actually be found or, as the liability waiver makes clear, even that they’ll be safe? Some light journalistic probing reveals a pretty narrow window of answers, from “for school credit” (a gently pimpled adolescent in a Texas A&M sweatshirt) to helping “the national cause” (a gravel-voiced man named Alex who works as a police officer in Dallas).

What quickly becomes clear is that I am the lone person who actually worries about any of this stuff happening. Any time I casually query the others about their heart rates or cortisol levels, given the day’s planned events, they sort of laugh me off and say, no, they don’t often think about plane crashes or mass shootings. Mostly they’re here because they were looking for a kooky way to spend a Saturday. Even when I mention the World Health Organization’s advisories about pandemic flus or the risk of biochemical attacks, my fellow victims either assume that I am engaging in some ironic, deadpan humor or treat me like a kid whose worries are downright Chicken Little–ish. Two older women make an aw-phooey gesture with their hands, and say, “Oh, bless your heart, sweetie.”

We congregate outside, under the building’s low portico, where Nyssa and LaNell are waiting for us with buckets of flour and ash. These materials will be our “makeup” for the Walking Wounded exercise, as we’re supposed to have been confected with all manner of hazardous chemicals. We stand on the grass, arms outstretched as if for crucifixion, and let the coordinators chuck handfuls of the stuff at our bodies and faces, until each of us resembles a beignet.

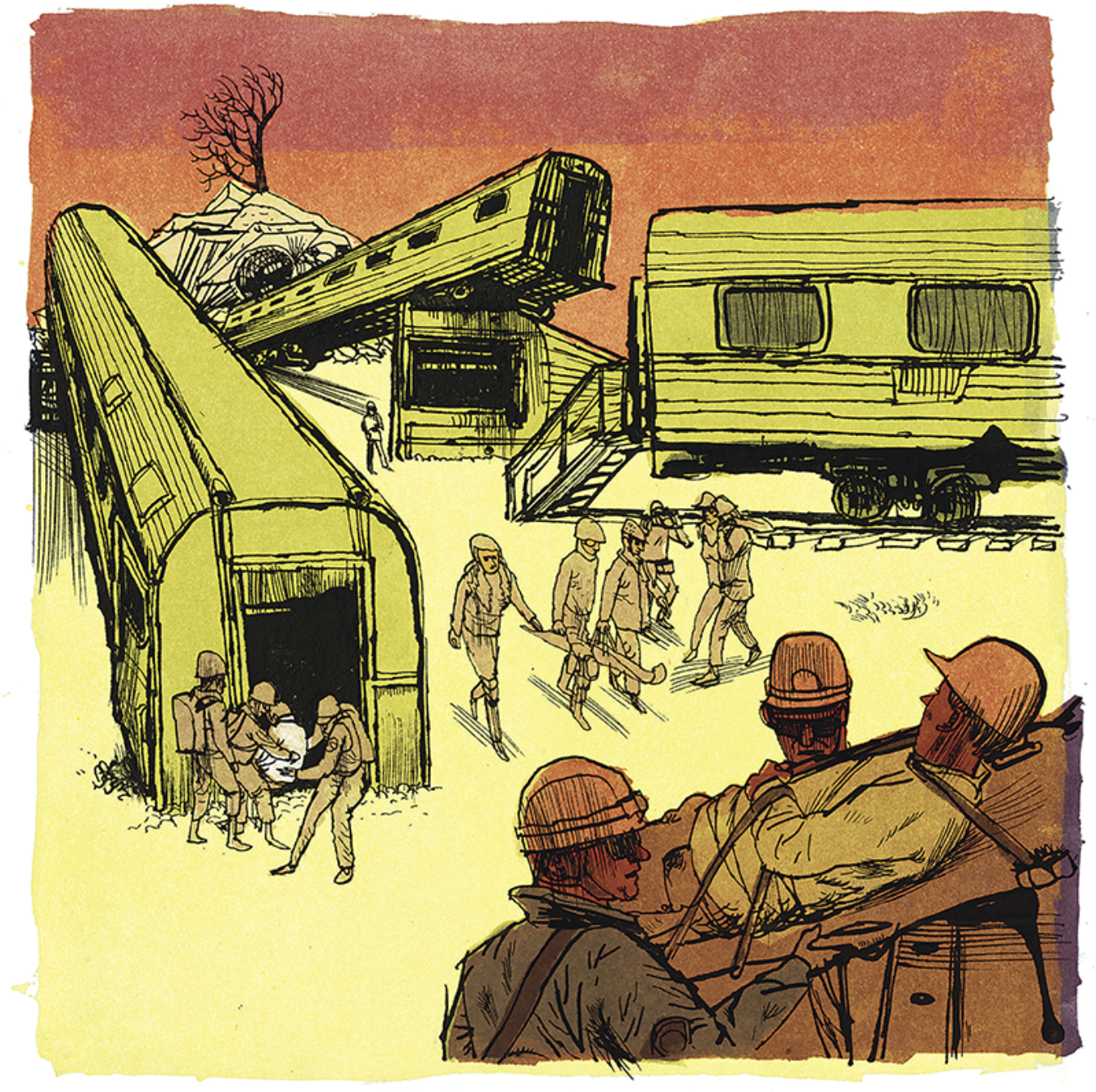

Powdered and primped, we are released into the streets of Disaster City, and I hang back and take it all in, since this is my first good look at the campus. From the top of the hill, what I’m afforded is a vista of gloom, a panorama of death and destruction. To my right is a full-size reenactment of a train derailment, with Amtrak passenger cars lying on top of one another and rusted midsize sedans pancaked between them. In the distance, there are two large hummocks of rubble, at least sixty feet high, which look like collapsed Jenga towers. Beneath these piles is a warren of tunnels where we victims will later be placed, the crevices of which, I’m told, are home to rats and scorpions, bobcats and snakes.

Most of these woeful tableaux have been modeled after the landscapes of actual disasters. For instance, a parking garage where two crushed and glittering cars dangle from a second story, their hoods pinned by a collapsed cement ceiling, was inspired by the World Trade Center bombing in 1993. If bombings aren’t your thing, you can slip into another building, where a full-scale replica of a suburban cinema sits ghoulishly empty. So vividly does it recall the Aurora movie theater shooting, you can’t help but skedaddle out of there and keep moving down the street. For obvious reasons, I steer clear of the tornado exhibit, where a storm has churned a two-story motel into a mound of chipper-shredded bits.

Theatrically speaking, I haven’t been that impressed by my fellow Victim Volunteers. Throughout the Walking Wounded exercise, most of them splinter off into little cliques of twos and threes, strolling laughingly down the debris-laden boulevards. One dramatic outlier is a stoic fellow named John Jahnke, whose Promethean cheekbones pretty much make him a dead ringer for Woody Harrelson. I sit down next to him on the collapsed roof of a fictional pancake house, and for a while we rest together in the accretive silence as he gazes pensively into the distance, like a sea captain recalling a traumatic voyage. Like most older eccentrics, he begins speaking without social nicety or contextualizing preface: “One of the things you learn right away is to get yourself to the high ground,” he says. “Because a lot of times if you’re not a victim in drastic need, they’ll leave you, so you want to be able to watch the action. If you get yourself into a place where you can’t see anything, well then it’s really a boring situation.”

Within the Disaster City community, John is considered to be something of a gray eminence. He’s been volunteering as a victim for the past ten years and has participated in as many as forty exercises. “I’ve been in that building there,” he says, pointing, “collapsed by a bomb. I’ve been in two of those cars there.” (He directs my attention to the cantilevered sedans on the far side of campus.) “And I’ve been in this store here, where my bomb blew up prematurely.” (I have no clue what he means by this.) He then gestures to the Stonehenge of Amtrak trains to our left, explaining that one time, after the first responders strapped him to a gurney, he kind of lost it psychologically. For the first time in his tenure as a Victim Volunteer, he realized that, in terms of realism, everyone has their limits.

In my interviews with the task force members, they kept referring to Disaster City as “a Disneyland for first responders.” Doubtless they were referring to the fact that Disaster City furnishes a whole Epcot of high-octane simulations, through which these guys get to practice assorted acts of heroism. But I’m inclined to think that the comparison between Disneyland and Disaster City is apt in ways I doubt they could have intended. After all, for nearly fifty years, critical theorists have been suggesting that Disneyland functions in the popular imagination as a locus of gauzy nostalgia, with its enchanted kingdoms and picturesque Main Streets harking back to some simpler, quainter time in American history that never actually existed. A similar nostalgia is at play here, too, but of a more upsetting kind. As you traipse down Disaster City’s own heavily themed Main Street, you see retail storefronts whose names are meant to evoke the mom-and-pop stores of some mythical hometown—Parker’s Hardware, Breaches Clothing Co., and Bennett’s Barbeque, whose tagline reads: saw ’em off and we’ll do the rest.

What thinkers like Baudrillard and Umberto Eco have posited is that the intense theming at Disneyland is, on some level, meant to convince Americans that the country outside the park’s turnstiles is real and authentic, when of course we know that Walmart and McDonald’s are just as flimsy and artificial as anything inside the Magic Kingdom—that American life itself depends upon narratives of enchantment. After a while I begin to think that beyond whatever preparatory education it hopes to impart, Disaster City’s true purpose is to concentrate every permutation of woe into one place, thereby allowing its visitors to believe that the world outside is comparatively safe. But what any obsessive-compulsive knows—and what the COVID-19 pandemic will make clear—is that the real world possesses far more threats and potentialities than exist in College Station.

At some point on Saturday, the simulation starts to break down, and it seems impossible to enumerate the many slippages between reality and recreation. Perhaps the most obvious example is my relationship with my press liaison, a person named Vita Vaughn. Anytime I’m not engaged in hair-raising simulations, Vita hovers in my vicinity, just in case I need anything. This is extremely unnerving in and of itself, but the plot soon becomes DeLillo-ish and postmodern, because it turns out that Vita is training to be a communications officer with Texas A&M Task Force 1 the next time they deploy. So even though I’m here as a credentialed representative of Harper’s Magazine, there’s a sense in which our interactions are serving as a dress rehearsal for Vita’s eventual conversations with real journalists. Vita tells me that she will eventually do mock press briefings, during which her colleagues in communications and marketing will sit in an ersatz media gallery and pummel her with questions while she stands at a lectern. Apparently they will try to stump her with facetious but heartrending ones, stuff like “But what about the babies, Vita? What about the babies?”

The blurriness between reality and its simulation gets intensified later, when Vita ferries me to the Texas A&M Task Force’s Base of Operations (also called “The Boo”), a massive encampment that from a distance looks rather like a Roman bivouac. Vita and I, wearing protective eyewear and requisite hard hats, slip into the tents and observe the guys in their navy-blue uniforms, all standing brawnily around and talking animatedly about casualty counts. Vita introduces me to Steve Lopez, a squat, muscular man who serves as the team leader of Texas A&M Task Force 2. But before I can even extend an introductory hand—a gesture that in three weeks’ time will strike me as unsafe—Steve squints in confusion and looks to Vita for clarification, saying, “Wait, like, is this real, or is this part of the simulation thing?”

In these interactions, Vita keeps misidentifying me as a writer from Harper’s Bazaar, which prompts me to waste a bunch of time wondering how a fashion magazine might cover the events at Disaster City: you down with ppe? yeah, you know me: how gloves, masks, and protective eyewear will soon become the new urban chic. Even so, most of the first responders seem terrified to be interviewed by me—one of them actually ducks behind a fellow task force member and says, jocularly, “Ask him, not me!” For a while, I’m puzzled by this caginess, until I realize that apart from saving lives, the task force is also responsible for controlling the disaster-response narrative, not only by sharing germane info, but also by exuding an attitude of superior competence and total control.

Vita introduces me to a task force member named Casey England, a trim, ginger-haired person with a wholesome farm-boy complexion. When I ask him whether these simulations ever wear on him, he says, “Yeah, man. I think they can.” He grew up just north of Oklahoma City, and when he was a sophomore in high school, he felt the 1995 bombing in his feet. His parents still live there, he tells me, and they’ve been to the memorial a few times, but when his mom asks if he wants to go, he says he doesn’t want to see it. “And she’s like, ‘Why? But this is what you do. You respond to things like that.’ And I told her, ‘Yeah, but when I do it, it’s not real.’ ” Even when he deploys for a genuine emergency, he tells me, he pretends it’s just training. He has to tell himself: “These aren’t real people. Those aren’t real lives. That’s not really their house. They didn’t just really lose their loved ones. It’s all a training exercise, and when I leave, it’s all gonna be okay.”

It isn’t until the Wet Decontamination Bath that the simulation starts to really mess with my head. At around 2:00 pm, I and two other Victim Volunteers are couriered over to the Decon Trailer, where men in hazmat suits and rubber boots the color of traffic cones proceed to cut away our clothes until we’re summarily reduced to our nethers. These men, breathing through long, dark, anteater-ish snouts, take us by the elbows and lead us to the bath. The Decon Trailer looks like a miniature car wash, with translucent noodles of plastic that you have to part like a stage curtain in order to get inside. Once there, I’m surrounded by pendent rubber hoses, each of which has a different function—wash, rinse, disinfect—and I’m made to stand in a little cylindrical basin while another guy in a hazmat tells me to lift my arms and open up my hands. When I do, he blasts me with a stream of icy water. “Is it cold?” he asks. “Yeah, man,” I say. “It’s fucking cold.” This makes him laugh.

Once I’m done with this humiliating ablution, I’m sort of birthed out of the plastic noodles on the Decon Trailer’s other end, and I stand dripping in the cold air while two other guys in hazmat suits scan my body with a toxicity detector that looks straight out of Inspector Gadget. And this is when I truly lose it. Because I realize that the whole ordeal is chillingly reminiscent of the sanitary protocols that Chinese doctors have been following in light of the COVID-19 epidemic, and for the first time, I feel like I’m inhabiting some future eventuality—that the simulation is grimly anticipating what in a few weeks’ time will become rote and commonplace, what many people will experience at hospitals all across the country.

This premonition won’t leave me even after the toxicity scan ends, because while this is supposed to be the country’s mecca of disaster preparedness, I find that no one—not the task force, or the National Guard, or the police or firefighters from the nearby city of Bryan—has thought to bring towels for us to dry off with. And so at this point I’m shivering visibly, like a cartoon of an electrocuted person, until one of the coordinators arrives on a four-wheeler to “rescue” me, and we cruise at ten miles per hour to the shower barracks on the opposite end of campus, where I am made to stand under a very hot faucet (presumably to decrease the risk of hypothermia) for what turns out to be like thirty minutes, because even this coordinator can’t find a towel for me or my compatriots. When he does return, he apologizes, saying he could only find “this.” I poke my head out periscopically above the shower curtain, and he hands me a pilled swatch of blue cloth that LaNell uses as a dog towel (readily identifiable by the tufts of German shepherd fur still matted to its fabric), along with three Disaster City T-shirts, which have the word victim emblazoned in bold black letters across the chest.

By now, my stress levels are so high that I don’t join the others in returning to Building 119 but instead abscond to the privacy of my car, where I become a veritable zoo of neurotic worries. Here I spend the next half hour trying to regroup and calm down, calling my wife and my mom, both of whom offer commiserative noises and keep saying, again and again, in assuasive tones, that there’s nothing to worry about, Barrett, that all of this is fake.

While the simulations at Disaster City were constructed for training and emergency preparedness, some of the earliest disaster mock-ups were designed for entertainment. At the crack of the twentieth century, visitors strolling down Surf Avenue in Coney Island could gawk at a reenactment of the Mount Pelée volcano eruption, which had occurred in 1902 on the French island of Martinique. Elsewhere they could clutch their hearts at a simulation of the Galveston Floods of 1900, a gruesome inundation that claimed the lives of more than eight thousand Texans. It isn’t hard to see how the interest in faux calamity was an attempt on the part of Americans to reconcile themselves to the horrific events that had become, by end of the Industrial Age, all too routine and expected. As the historian Ted Steinberg puts it, there existed no better way to come to grips with “the anxiety spawned by the spate of turn-of-the-century disasters than to schedule a trial run with apocalypse.”

Steinberg contends that these simulations ended up having a more insidious social function, working to normalize disasters and thus sap them of any larger political message. Up until the early twentieth century, government officials were apt to characterize natural disasters as “acts of God,” a convenient rhetorical maneuver that blamed any calamity on the fickle whims of Heaven and sought to keep the engine of industrial capital chugging toward productivity and profit. Such logic came at the expense of citizen safety, perpetuating the very conditions—irresponsible land development, slipshod fire codes, shoddy masonry—that often caused these disasters in the first place.

One of history’s more glaring examples of this tendency, as Steinberg notes in his book Acts of God, involves the railroad magnate Henry Flagler. In 1905, after constructing a rail line from Jacksonville to Miami, Flagler proposed building an ambitious track that would extend from Homestead to Key West, hoping to exploit the surge of maritime commerce created by the West Indies. The project came with a price tag of $2 million and required forty thousand workers, some seven hundred of whom drowned on the job during one or another of that decade’s frequent hurricanes. In response to each storm, Flagler apparently reacted with a two-word telegram: “Keep going.” Later analysis of the project revealed that the rail line had inhibited tidewaters along the Keys from receding, which amplified water levels during intense storms and put communities at greater risk. Sure enough, during the 1935 hurricane in Islamorada, Florida, roughly two thirds of the residents were dragged from their homes and carried out to sea.

Up until this point, the state of Florida had maintained a strict “see no hurricane” policy, so as to attract residents and land developers. But after the Islamorada disaster, the media, which had taken to calling the storms “the Florida Hurricanes,” shamed its government into acknowledging the state’s outsized flood risk. While this led to some meager reforms in insurance policies, the more lasting consequence was the countervailing effort by the government to dissociate Florida from these tempests. They were aided in that effort by the U.S. Weather Bureau, which, in 1950, decided to give storms female names. Cheap misogyny aside, a more subtle machination was at work here, because by associating storms with women and the brain-dead stereotypes about them (fickle, erratic, unpredictable), the authorities were going a step further in naturalizing these events, suggesting that Mother Nature could not be anticipated or mitigated but must be countenanced instead as merely the cost of doing business.

After the Decontamination Bath, I eventually return to Building 119, where LaNell gives us notecards with descriptions of our dramatic roles for the Rubble Entombment. At the top of mine are boldface letters reading tango 26, followed by stage directions. For this scenario, I will be in a “large, survivable void,” but I’ll only be able to tap lightly on the walls around me (“skin or wood on concrete”). “If not found by 7:00 pm on Saturday,” the instructions read, “begin lightly tapping with a rock on concrete ONLY when requested. If not found by 9:00 pm, begin tapping loudly with a rock until found. You cannot talk, but you can follow searchers’ commands.” If I have an emergency or real-world problem, I’m supposed to yell “Real World,” “For Real,” or “Code Purple.”

Now the volunteers are leaning over and sharing their notecards, jealously appraising one another’s assignments like, “Hey, what did you get?” I turn to a woman named Denise—the person who fell asleep in the rubble pile last year and was forgotten about for seven hours—and I ask her, “Is this right? If I’m not found by nine o’clock, start banging on the wall with a rock?” And she goes, “If you’re not found by nine o’clock, I’d recommend you start screaming.”

Tango 26 is located in Rubble Pile 2, Hot Zone 1, a sector nestled between the strip mall and the half-collapsed parking garage. Wearing my leather gloves and hard hat, I clumsily ascend an Everest of rebar and concrete, at the top of which is a haphazard stack of wooden pallets, which Casey, the first responder from Oklahoma, begins chucking out of the way. In time he reveals a twelve-foot sheet of plywood that will essentially function as the lid of my coffin. Casey lifts it up and rests it on his shoulder, positioning himself in the braced squat of a shot-putter. “In you go,” he says. I peer into the catacomb, and my nostrils are assaulted by the scent of mold and mud. Its floor is a shallow broth of mulch-colored water.

“Wait a minute,” I say, “this is me?”

“This is you,” he says.

I hop into my crypt, where I’m newly flooded with anxiety. Before he closes the lid, I ask, “Hey, Casey, this is all fake, right?” And he says, “Yessir, it’s all training.” I listen to the scrap and clatter of pallets being piled on top of me and will myself into a kind of self-protective fugue state.

The first hour passes with a lot of controlled breathing. I make a game of training my gaze on the granular swirl of concrete, treating the wall as one of those optical-illusion posters. My tomb is the size of a really large household appliance—think dishwasher or storage cooler—and I have to scrunch my knees up into a vinyasa squat in order to fit. The tomb’s lone feature of hope is a shard of daylight that squeaks through one corner of the ceiling so that I can just barely see a blessed shred of sky. Basically, I will treat this shard of daylight the same way that Tom Hanks treats the volleyball in Cast Away.

It doesn’t take me long to realize that I’m surrounded by other victims. When I press my ear to the concrete wall, I can make out someone snoring. Somewhere to my right is a Victim Volunteer named Fred, who keeps caterwauling his own name and pleading for someone to help him. Fred is also clanging a stone against a piece of rebar, which produces a sound that recalls the brassy staccato of chain gangs or maybe an Old West prisoner dragging a tin cup across the bars of his cage. For a while I use a rock to tap out in Morse code, “Hey, Fred. Please shut the fuck up,” but either Fred isn’t listening or he’s unacquainted with emergency communication tactics. As time passes, I come to regard Fred as a strange kind of cellmate, the psychodrama between us playing out through a makeshift system of taps and clanks. We do a call-and-response-type thing that I actually find quite solacing—its subtext is, You’re not alone in this—but then Fred is back to shrieking his own name, and I have the morbid wish that, in the simulation, anyway, Fred would just die already.

For my stint in the rubble, I’ve brought with me two books—An Actor Prepares (a vade mecum for Method acting) and Everyday Mindfulness for OCD (which has been helpful in curbing my anxieties)—but because Baudrillard has been on my mind all weekend, I decide to download his The Evil Demon of Images onto my phone. In it, Baudrillard contends that the most nefarious aspect of any simulation is the degree to which it can produce reality even before it happens, thereby inuring us to calamities and preempting any meaningful response we might have to them. It makes me think of Hurricane Pam, a Category 3 storm that hit New Orleans in 2004 and damaged more than half a million buildings. If you don’t remember Hurricane Pam, well, that’s because it never happened. Instead, as Robert C. Bell and Robert M. Ficociello note in their book America’s Disaster Culture, it was a simulation created by a FEMA contractor that wanted to demonstrate how overwhelmed response teams would be if a bad storm came through and the city had not improved its emergency plan. An imaginary storm with 120-mph winds and rains in excess of twenty inches, Hurricane Pam predicted, with a kind of prophetic accuracy, the devastating aftereffects of Hurricane Katrina. But both the local and federal governments were unwilling to heed the contractor’s advice and failed to address the underlying problems—poverty, crumbling levees, an unjust health care system—that would give rise to a crisis. In the end, Hurricane Pam did little but give our country a false sense of preparedness. Or as Bell and Ficociello put it, “the simulation precedes and actually creates the disaster.”

Locked in my crypt, I find myself googling “simulation covid epidemic.” Almost immediately I stumble across a YouTube video for something called “Event 201,” a pandemic exercise that was carried out in October 2019—only two months before the COVID-19 outbreak. Event 201 was overseen by the World Economic Forum, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Its organizers went so far as to produce fake news segments on something called GNN, or Global News Network, whose anchors outline, in harried voices, the fictional virus’s lethal consequences. “It began in healthy-looking pigs,” one anchor says, months, perhaps years ago. A new coronavirus spread silently within herds. Gradually, farmers started getting sick. Infected people got a respiratory illness with symptoms ranging from mild, flu-like signs to severe pneumonia. The sickest required intensive care. Many died. Experts agree unless it is quickly controlled it could lead to a severe pandemic, an outbreak that circles the globe and affects people everywhere.

The goal of the Event 201 Pandemic Emergency Board, which included Adrian Thomas from Johnson & Johnson, Sofia Borges from the UN Foundation, Christopher Elias from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and George Gao from China’s CDC, was to provide recommendations for responding to the challenges that would be created by a worldwide pandemic. So eerily and uncannily did this group anticipate deaths, travel bans, and economic ripple effects that I find myself returning to the simulation again and again, almost as if it were a compulsion.

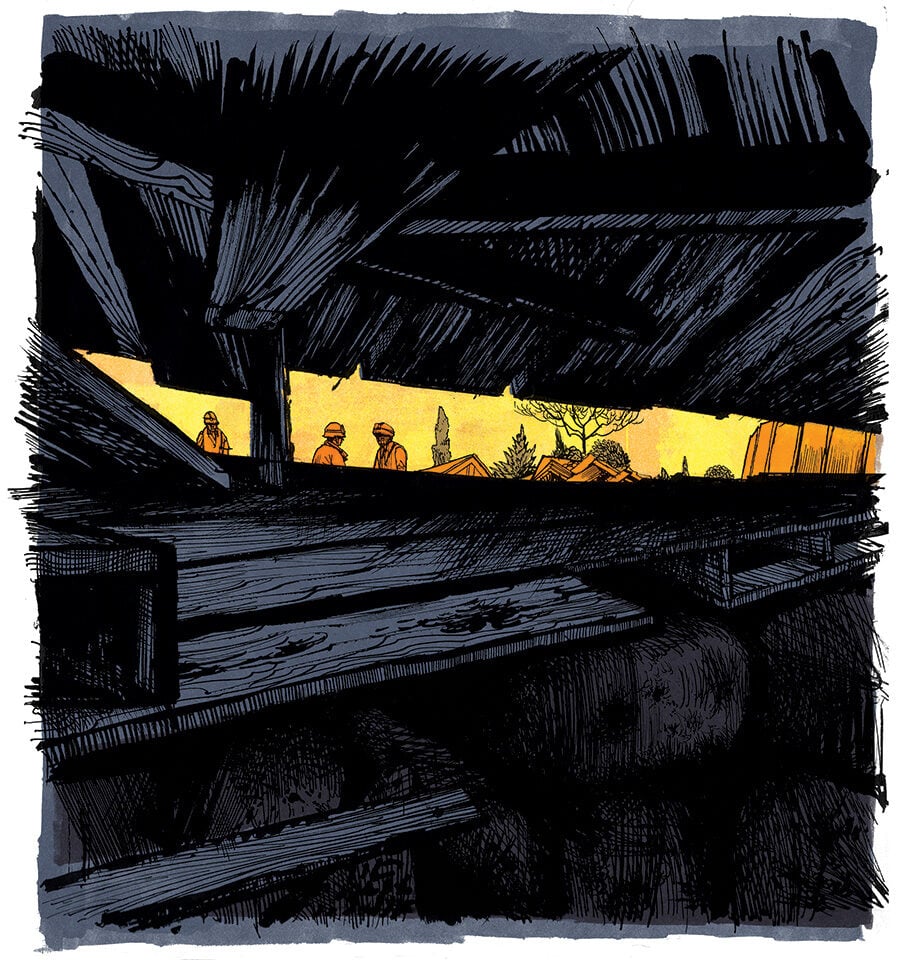

I’m shaken out of these reveries by the sound of rescuers approaching. What comes first is the wet respiration of their SCBAs, then the thump of their footfalls overhead—the papery scrape of gravel, the molar crack of stone. “Search and rescue!” they yell. “Is anybody in there?” And even though I’m banging my fist so forcefully against the wall that my forearm is throbbing, they of course don’t find me but instead locate my deranged cellmate Fred. As it happens, Fred doesn’t remember his stage directions, because when they ask him if he’s hurt, Fred says, “Uh, I don’t actually know if I can move. I guess I’ll have to take my physical condition from you”—the disaster-simulation equivalent of an actor stopping mid-scene and bellowing, “Line!”

Soon I hear the low mutter of trucks, plus the staticky cadence of the EMTs’ walkie-talkies retreating into the distance. It’s hard to describe the desolation I feel as my little sliver of sky darkens, going from the milky blue of late afternoon to the bruise-like indigo of early evening, a gradient change that suggests I may be staying here for the rest of the night. A fellow Victim Volunteer, who is a seasoned thespian on the disaster-simulation circuit, calls this “The Hour of Doom.” (In fact, because the task force didn’t find me, the Observer Controllers decide to bring me out after another two hours, and I have to climb unceremoniously out of the tomb myself.)

For the time being, though, crumpled in the rubble pile, compulsively tapping on my cement wall, I start to understand what’s been bugging me about Disaster City all weekend. I get the sense that I’m not just enacting a disaster’s typical response but playing a role in a palliative narrative, instantiating a myth that the country repeatedly tells itself about tragedies of all sorts—that there was nothing we could have done, that there is no one to blame. After all, the very existence of a place like this seems to sanction and sacralize the inevitability of catastrophes. Each simulation is not a true attempt at prevention but an exercise in containment and restoration, which we’ve blithely come to accept as an adequate disaster response. By now, it should go without saying that the warnings of Hurricane Pam and Event 201 were not heeded, since the cost of their recommendations would have necessitated fundamental changes to our existing social system. Later, I ask Stephen Bjune of Texas A&M Task Force 1 whether FEMA teams are ever consulted by developers or municipalities, particularly when cities are legislating on fire codes or building regulations. He sighs and pauses for a moment, before saying, “No, unfortunately.”

Four weeks later, I will once again be in confinement, but this time as part of a quarantine, the Great American Cloistering of 2020. As the real disaster unfolds, members of Texas A&M Task Force 1 will help enforce social distancing, and their hazmat practice in late February will turn out to have been serendipitous.

From my bunker of self-isolation, I will engage in such assiduous routines of decontamination that by late March my house will reek of Pine-Sol and disinfectant, and my hands will be scrubbed and pumiced, as clean as an infant’s conscience. But by that point, my habits will no longer feel like neurosis: the whole nation will have become roaringly obsessive-compulsive. How quickly the memes of sudsy hands start to proliferate, the YouTube clips of proper washing techniques. Celebrities will exhort their followers to rinse for at least twenty seconds, and even Google will get into the sanitation game, changing its homepage logo to a cartoon of Ignaz Semmelweis—the Hungarian physician and father of modern antiseptics (about whom I wrote a four-page paper when I was ten or eleven).

Beyond these convergences with my childhood obsessions, what will strike me most is how quickly the virus gets placed inside our familiar disaster narratives. Once the disease hits American cities, a swift linguistic campaign will get under way, with talking heads casting COVID-19 as an unforeseen and unpredictable menace, one in which human institutions could not be complicit. The examples of this tendency will be as frequent as they are abhorrent. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin: “No one expected this.” Senator Mitt Romney: “This is an act of nature.” Prospect magazine: “It is essentially an ‘Act of God.’ ” Fox News contributor Stephen Moore: “An act of nature.” Even the Gray Lady will participate in this naturalization, suggesting that “this crisis is caused by an act of nature that has struck at least 113 countries” rather than by “irresponsible policies.”

But perhaps the truest measure of our historical amnesia will be the scores of American companies that will cite acts of God clauses in order to avoid the EPA regulations in their government contracts. One corporate lawyer, Brian Israel of Arnold & Porter, will say that by early March his firm had fielded at least one request from a company that claimed it could not perform groundwater testing because its employees were unwilling to work during the worst throes of the pandemic. The EPA is likely to approve such requests, despite the fact that the World Health Organization has found that climate change accelerates the spread of infectious diseases and that man-made environmental degradation—particularly in the form of deforestation, which pushes disease-bearing species out of natural habitats and into cities—has been linked to 31 percent of new viral outbreaks.

Cloistered in my apartment, surrounded by empty Purell bottles and dry Clorox wipes, I will watch, with fear and loathing, as the wheels of disaster capitalism begin to turn and accelerate: Trump will propose that we end the payroll tax; the pharmaceutical lobby will angle to secure profits for a vaccine. With dismay, I will watch as Americans express their willingness to forfeit their civil liberties in the name of new surveillance measures, violating Ben Franklin’s grievously forgotten saying, “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.” Or as the disaster scholar Scott Gabriel Knowles puts it,

Countenancing lies about preparedness because they make us feel safe is a weak response to government . . . it makes it possible for policy makers to pursue actions that citizens may not approve or even be aware of, or if they are aware, may not fully understand due to “wartime” security measures.

It’s this line of thinking that will haunt me during the quarantine, watching from my apartment window as lights glow in other buildings, each of my neighbors zoning out to a flickering screen. All of our interactions are now virtual—all of us now live in the simulation—a place where it is increasingly difficult to distinguish between what is real and what is imagined, between which fears are legitimate and which are obsessive-compulsive. Isolated in my own neuroses, I can’t say for certain how we got here, though I sense that it has little to do with acts of God or even acts of nature.

Disaster preparedness is not, in the end, the same as disaster prevention. The latter would require something that is, from our current vantage, inconceivable: the political will to abandon the pernicious practices that currently support our economy. It would require a reckoning with human agency, an acknowledgment that no matter the scope of the disaster, no matter the exertions of essential workers, no matter how many times we bleach and scrub, rinse and disinfect, all of this is merely triage. We keep washing, but our hands are not clean.