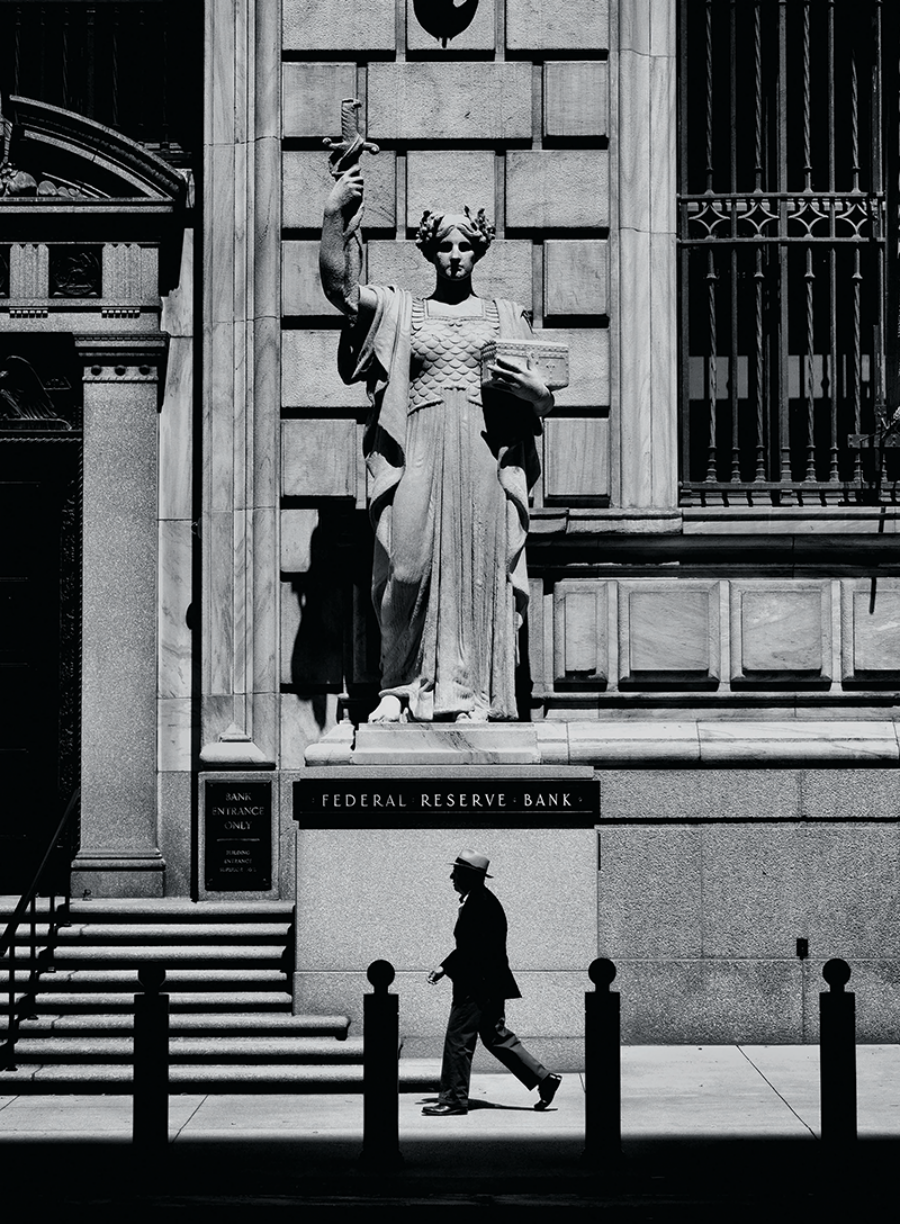

Downtown Cleveland, 2016 (detail) © Matt Black/Magnum Photos. All photographs by Black are from the Geography of Poverty series.

Dedicating the long-delayed Franklin Delano Roosevelt memorial on a sunny May morning in 1997, President Bill Clinton drew enthusiastic applause when he spoke of a “strange irony”: although a quarter of Americans were unemployed in 1932, that figure had shrunk to “fewer than one in twenty,” marking a time of “unprecedented prosperity.”

If the trauma of the Depression years—vividly evoked in the memorial’s sculptures and inscriptions—seemed remote to Clinton’s audience, it has an entirely contemporary feel today. One striking tableau features a row of cold and hungry men waiting outside a door for food—a breadline. “Today we call that…