The Lightning Farm

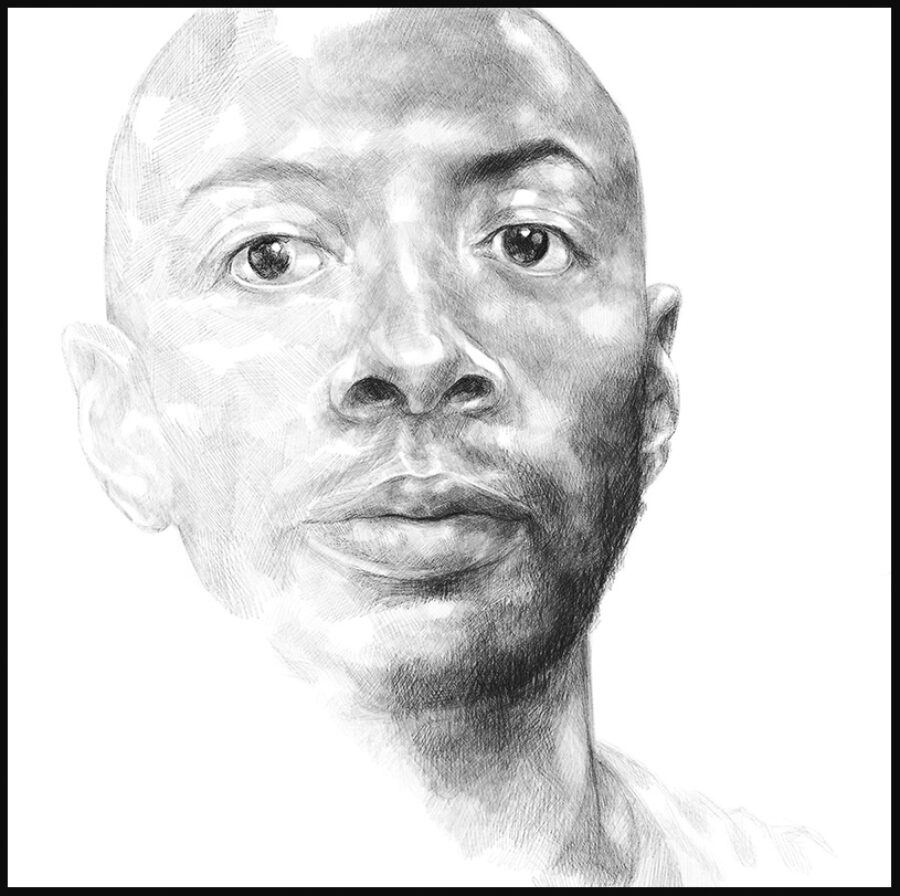

Dustin John Higgs, 2021, by Toyin Ojih Odutola for Harper’s Magazine © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City

The Lightning Farm

The sole federal execution chamber in the United States is in a place called Terre Haute—the high ground—in far western Indiana, named for a swath of land that rises above the nearby Wabash River. The surrounding country is in fact flat and wide, precipitously exposed to the sky.

The prison complex—south of downtown via Route 150, past the dome and bell tower of the Vigo County courthouse, and after the Tire Barn on Spring Hill Road—comprises the medium-security Federal Correctional Institution and the maximum-security U.S. Penitentiary, the home of the Special Confinement Unit: death row and the death house, a low, windowless building of dark-red brick on the northern edge of the grounds.

Terre Haute was selected as the site for federal killings in 1993—amid a rise in capital sentencing following a twenty-year lull—because of its central location in the country. The death chamber there was first used in 2001, in the execution of Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber, who was killed by what is now considered the traditional lethal-injection cocktail of three drugs: sodium thiopental, an anesthetic; pancuronium bromide, a muscle relaxant that effects asphyxiation; and potassium chloride, a salt that causes cardiac arrest. The anesthetic effect of the first is understood to be short-lived; the last, it has been claimed in court, feels as though one is “being burned alive from the inside.”

McVeigh’s was the first federal execution in thirty-eight years. Following him, the chamber was used twice more under the George W. Bush Administration, and then left idle for almost two decades.

In July 2020, the Trump Administration resumed federal executions, and in its final seven months killed thirteen people, more than had ever been put to death by the federal government in so brief a period. It was the most in a year since 1896—including an unprecedented five lame-duck killings—and more than all the states combined in the same year, a feat never before achieved. And the undertaking was even more nasty and hurried than the numbers convey, the executions rammed forward at each closed door by an administration that would forever be known for such force.

I arrived in Terre Haute on January 15, the day of the last scheduled killing, and what would possibly be the final federal execution of the modern era. In five days, Joe Biden would take office and the death chamber would be stilled again: no executions could take place without his approval and he had made his position clear. Though he’d supported the penalty in his tough-on-crime years and as late as the Aughts, as a candidate in 2020 he’d promised to end capital punishment at the federal level and to push states to follow suit. His selected attorney general, Merrick Garland, had been the lead official in the Department of Justice who pursued and secured the death sentence for McVeigh, but he too had turned with the times. The realities of the penalty’s application over the intervening twenty years, he would soon note in his confirmation hearing, had given him “great pause.”

Twenty-two states already prohibited the penalty, and twelve others hadn’t carried out an execution in more than a decade. In late 2019, polling showed for the first time that a majority of Americans supported life in prison over death sentences. A few days before I traveled to Terre Haute, Representative Ayanna Pressley and Senator Dick Durbin announced a joint bill to end the penalty, endorsed then by more than seventy others in Congress.

The man scheduled to die last was Dustin John Higgs, a forty-eight-year-old black man, whom the role seemed to fit no more than any other person on death row. His sister Alexa Cave-Wingate had asked her whole church to pray.1 “Just give me six days,” she told a reporter on Thursday, January 14. “I don’t care if it’s a stay or a reprieve, whatever. Six days is all I pray for.”

On the lobby level of the Terre Haute Marriott, on Friday morning, Shawn Nolan, Higgs’s lead attorney, could be seen using the printer and scanner of the hotel’s business center to handle the day’s appeals. Higgs’s spiritual adviser, Yusuf Nur, the only person who could accompany Higgs into the death chamber, sat nearby, not far from Alexa, who was being interviewed by a reporter. Activists wandered through, on their way to the picket across the street from the prison, about a five-minute drive south. It was rumored that the executioners—private contractors from out of town, who were paid in cash—were staying at the hotel, too. During the first spate of executions, in the summer, guests had seen an unmarked white van—the same as those used by the Bureau of Prisons—pick up a group of men “looking,” they said, “like Blackwater dudes.”

I greeted Nolan quickly, as he was busy with the details of a filing. He was unshaven and wearing a green fleece he’d had on for two days. The night before, the Supreme Court had rejected, without explanation, a claim on behalf of Higgs and Corey Johnson—the second-to-last inmate scheduled to die—that lung damage both men had sustained from COVID-19 infections would aggravate the already torturous experience of lethal injection. (By mid-January, death-row lawyers believe, at least twenty-nine of the remaining forty-seven inmates had contracted COVID-19.)

Higgs now had two outstanding lawsuits—one regarding information improperly withheld during his trial, and another appealing to a federal law requiring that prisoners be executed under the rules of the state in which they were sentenced. Higgs was sentenced in Maryland, which had abolished the death penalty in 2013, presenting a substantial legal question never before addressed in the courts. Nolan had previously brought this issue to the Fourth Circuit, which agreed it needed consideration and granted a stay of Higgs’s execution and an appeal hearing, set for January 27. But the DOJ had intervened and asked the Supreme Court to bypass the Fourth Circuit—to rule “before judgment”—a capability intended to be used, according to the court, in cases of “imperative public importance.” Nolan told me that granting the request in the case of an execution would be unheard of, and on Friday morning he believed the Supreme Court might leave the Fourth Circuit decision, and the stay, untouched. He filed a response in opposition to the DOJ.

Nolan had watched as each of the twelve inmates before Higgs had lost their appeals and had their lives dispatched like paperwork. But when I spoke to him again later in the day, he sounded strikingly upbeat. I was in my car, parked in front of a white clapboard house, on a dirt route called Justice Road, which I would later learn led directly to the death house. It was blocked about a hundred yards ahead by an unmarked car and two guards armed with long guns. “If this goes well tonight,” Nolan said, at the other end of the line, “come drink some wine with us in the lobby.”

When the Supreme Court briefly suspended the death penalty in the United States in 1972, in Furman v. Georgia, it ruled narrowly, finding that capital punishment, at that time, was cruel and unusual because its imposition was arbitrary. The court agreed with attorneys of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund that the decision-making power given to states, judges, and juries was too broad, and that the demonstrably irregular application of the penalty, while unfair on its face, also allowed for racial bias, weighing heavily against black Americans.

“These death sentences,” wrote Justice Potter Stewart, on the side of the majority, “are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual.” The petitioners in the case, he found, were “among a capriciously selected random handful,” and if any clear criterion could be identified, it was the “constitutionally impermissible basis of race.” The Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, he said, could not “tolerate” a sentence of death “so wantonly and so freakishly” doled.

In response, in the following years, thirty-five states enacted new laws and regulations intended to guide capital sentencing: mandatory death penalties for particular crimes; new penal codes delineating death-eligible offenses; and the new widespread process of sentencing hearings, separated for the first time from convictions. In 1976, in the case of Gregg v. Georgia, the Supreme Court was asked to further its ruling against the penalty and grant that it violated the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments in all circumstances. Instead, it found that capital punishment was constitutional when sentencing was directed by “carefully drafted statute” and met with “adequate information,” as it was, the court said, under Georgia’s new processes. In effect, the constitutional problem of “arbitrariness” was resolved, and the moratorium on the penalty was lifted.

Over the past half-century, the death penalty in the United States has been upheld by the myth that the state can kill fairly. Since the mid-Seventies, the jurisprudence of capital punishment has moved consistently to impose order throughout the system, from conviction to execution, and this effort has traveled hand in hand with attempts to make the executions themselves appear benign or even benevolent—in the words of one scholar, “medico-bureaucratic”; and in those of a former constitutional standard, limited to “the mere extinguishment of life.” Today, executions cannot be carried out with any “purpose to inflict unnecessary pain.” Unlike in the earlier history of the United States and in many societies before us, in which the state derived power from the violent public spectacle of capital punishment, the U.S. in the past fifty years has asserted the legitimacy of the penalty by working to make its force appear less terrible, and the killings less like murder—this is also to say, according to the legal scholar Austin Sarat, less like lynchings.

Though the way prejudices are refracted through the capital-punishment system has shifted, the arbitrary nature and unequal imposition of the death penalty remains. Forty-one percent of death-row inmates nationally are black, and 75 percent of victims of capital crimes are white. Of those sentenced to death who are later exonerated, 54 percent are black; 64 percent are non-white. Every person currently on federal death row is indigent, and all relied in their original trials on court-appointed lawyers.

Trump’s DOJ blew past the guardrails of the capital system in ways that underscored the farce of the states’ and courts’ efforts. But decisions of death have always ultimately reached a legal abyss. “The law,” as Sarat put it, “runs out.”

How and why the Trump Administration resumed executions when it did was not as simple as it appeared from the outside. It was not merely a late rush to kill while Trump and William Barr, and later Jeffrey Rosen, still had the chance, but the result of efforts taken at the administration’s start and even before.

In 2017, when Attorney General Jeff Sessions took the helm at the DOJ, he inherited an Obama Administration problem: the Bureau of Prisons could not obtain enough sodium thiopental, the anesthetic in the triad dose that had killed McVeigh and was required by federal execution protocol. In a 2011 letter, Attorney General Eric Holder called the lack of the drug a “serious concern,” and the DOJ and BOP by that year began considering a change to the protocol, investigating feasible alternatives. When this inquiry was resumed under Sessions, the DOJ focused on a potential single-drug replacement: pentobarbital, a sedative and antiepileptic used for state executions since 2011. But it too was difficult to obtain—a perennial problem for substances sought for lethal injections. (The DOJ and BOP also considered fentanyl, the synthetic narcotic, though the bureau noted that this might attract “negative publicity.”)

It was under Bill Barr, in July 2019, that the rules changed. Federal executions, he announced, would now be carried out with pentobarbital: two syringes of 2.5 grams each, followed, as in a medical procedure, by a third syringe of saline. According to dozens of lawsuits and hundreds of filings on behalf of death-row inmates in the year and a half following Barr’s announcement, the new protocol violated at least seven laws, including the Federal Death Penalty Act (FDPA) and the Administrative Procedure Act; numerous laws and regulations relating to the DEA, FDA, BOP, and U.S. Marshals; and at least four constitutional amendments, including the First, Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth.

Importantly, the use of independent federal rules was said to be illegal. Though the DOJ had been following its own protocol since at least the early Aughts, the FDPA mandated that the federal government execute inmates according to the rules of the state in which they were sentenced—the same provision at the center of Higgs’s final appeal.

Lawyers further claimed that the use of pentobarbital, specifically, was unconstitutional. Autopsies of inmates executed by states had shown the drug to cause flash pulmonary edema—an onrush of fluid into the lungs, which would induce the sensation of drowning, filings asserted, in a foam-like substance produced as the liquid mixed with alveolar air. Pentobarbital was also said to cause “unresponsiveness, not unconsciousness.” It was a “virtual medical certainty,” in the words of one testifying doctor, “that most, if not all, prisoners” would experience “excruciating suffering.” Adding fentanyl to the process, lawyers maintained, would be far more humane, as would abandoning the injections for firing squads.

Each of these challenges failed or went unheard, but they were a significant nuisance to the DOJ. And at the end of November 2020, when halfway through his execution docket, Barr changed the protocol once again, seemingly to allow a wider berth around future lawsuits. The approved means of federal execution now included firing squad, lethal gas, and electrocution.

At the same time as his July 2019 fiat allowing pentobarbital, Barr had announced the names of the first five people the DOJ intended to execute. After a year of litigation, this list was revised to four names, and released publicly without forewarning to death-row inmates in June 2020. These appointments would stick.

In July, Dustin Higgs called Alexa, in Atlanta, from a phone handed through a slot in the door of his cell, as he had almost every day for twenty years. Alexa loved their conversations and looked forward to hearing the automated recording when she picked up, letting her know she had a prepaid call from a federal prison.

Both Higgs and his sister had heard that executions were coming. Higgs was scared, and Alexa said it would be all right. After a couple months, she said, she started to feel that way—“hopeful that they wouldn’t call his name.” There were sixty-two people on death row, and at least eight had been there longer than Higgs. The odds of his being picked seemed low.

But in September he called with news. “I just wanted to let you know,” he said, “before we get into anything else, that I heard through the grapevine that my name is coming up on the list.” His sister said she didn’t understand. “The execution,” he told her. But a rumor was just a rumor.

Through public notices and court-ordered depositions, Trump’s DOJ claimed that there had been a rational process behind the selection of the inmates to be killed. The true calculations, however, have remained opaque. In January 2020, when lawyers representing different death-row defendants deposed Bradley Weinsheimer, a deputy attorney general, Weinsheimer stated repeatedly that the BOP had found these prisoners to have “exhausted their appellate and post-conviction remedies.” However, depending on the intent, this was either a narrow legal distinction, which said nothing of appeals that might arrive due to newly introduced evidence or arguments, or it was an assessment the government could not make. In fact, eight of the thirteen people ultimately selected had appeals in process when their execution dates were announced. And as new challenges and stays ran up against the appointed execution dates and times, the Supreme Court consistently voted to dismiss litigation and heed the calendar set by the DOJ. Wesley Purkey, who died on the morning of July 16, in the first week of executions, was killed while an appeal was still pending—that is, before the court had even dismissed it. Pieter Van Tol, who was part of a team of attorneys who deposed Weinsheimer, told me, “I have never been more afraid of the government than I was after those seven months.”

In DOJ communiqués, the original five inmates Barr named for execution were said to have been chosen because they had harmed “the most vulnerable in our society—children and the elderly.” This held up somewhat but not entirely, and when Weinsheimer was pressed on this, he recited the words from the department’s public notices repeatedly—it was “like a mantra,” a defense lawyer present told me. For Barr’s revised, June 2020 list of names, the DOJ stated that all had been convicted of “murdering children.” But this still was not wholly correct. And these goalposts moved as the year went on. When the execution dates for inmates Lisa Montgomery and Brandon Bernard were announced in October, the claimed criterion had become that of crimes that were “especially heinous,” a phrase that has appeared at some point in the capital-sentencing statutes of at least nineteen states, and has long been criticized as vague. While some states defined this standard for their purposes, the DOJ did not. A defense attorney who has worked with dozens of death-row inmates told me that the prisoners were terrified as the names were drawn. “These are people thinking,” she said, “There but for the grace of God go I.”

A week before Thanksgiving, Higgs called his sister again. “I got a date,” he said. His crime was among a group of three judged by the DOJ, in November, to be “staggeringly brutal.”

On January 26, 1996, Higgs and two friends, Willis Haynes and Victor Gloria, spent the evening with three young women—Tanji Jackson, twenty-one, Mishann Chinn, twenty-three, and Tamika Black, nineteen. (Higgs, Haynes, and Gloria were twenty-three, eighteen, and nineteen, respectively.) It was a sort of triple date, arranged by Jackson and Higgs. The men picked the women up in Washington, D.C., and brought them back to Higgs’s apartment in Laurel, Maryland, where they drank and listened to music. The men had in fact been drinking all day—by night, fifths of cognac—and they rolled and smoked blunts made from White Owl cigars. According to testimony by Haynes and Gloria, when Higgs and Jackson were alone, Higgs propositioned her and she refused. The two began to argue, and Jackson grabbed a kitchen knife. Haynes, who had been in the apartment’s bedroom with Black, came out and convinced Jackson to drop it. The women left, and according to Gloria, on the way out, Jackson “stopped at the door, and said something like, ‘I am going to get you all fucked up.’ ” Watching from the window, Higgs saw her write down his license plate number—the next morning, the police would find it scrawled into her datebook, alongside his nickname, Bones; telephone number; and address.

Gloria and Haynes both later testified that Higgs felt threatened, and Gloria claimed that Higgs thought Jackson knew dangerous people. It is unclear who those would have been. Both Higgs and Haynes were dealers, selling crack cocaine. Jackson worked in the office of a high school. Chinn worked with the children’s choir of a Baptist church, and Black was an elementary-school teacher’s aide.

The women took off on foot. The men followed and offered them a ride home. It would be a thirty-minute trip—Higgs’s apartment was right off the Baltimore-Washington Parkway. But instead of turning toward D.C., Higgs, who was driving, continued straight, entering the Patuxent National Wildlife Refuge, which borders the interstate. According to prosecutors, the women were ordered out of the car, and Higgs handed Haynes a .38-caliber pistol, telling him, “Better make sure they’re dead.” An hour later, a driver discovered the three women’s bodies lying in the southbound lane of the parkway, one eighty yards removed from the others.

In the words of Mishann Chinn’s mother in 2000, the families of the victims waited “1,700 days” for resolution. Higgs was formally sentenced on January 3, 2001—two weeks after Timothy McVeigh ended his own appeals, effectively accepting his execution. Questions of the morality and justness of capital punishment were very much in the air, and the presiding judge took special pains to state that these concerns did not apply to Higgs, whose guilt, he said, was certain, and who would be remembered “as a cold-blooded killer.”

Prosecutors had sought the death penalty for Haynes as well, but his jury declined, and he was given a life sentence. (In an interview with the Baltimore Sun at the time, Maryland U.S. Attorney Lynne A. Battaglia said that it was impossible to know why the two juries had diverged.) In Higgs’s trial, the government argued that he, five years older than Haynes, had forced the murders by intimidation, and their case depended on the testimony of Gloria and Haynes. Gloria would prove an unreliable witness, making conflicting statements regarding key moments in the crime. He was also granted a plea deal of seven years in exchange for his testimony, which Higgs’s defense would later allege had included additional dropped charges in a separate, unrelated murder investigation. Further questions subsequently arose about Gloria’s soundness of mind.

As for Haynes, twelve years after the trials he penned a declaration that called the prosecution’s theory—and, by implication, his own previous claims—“bullshit.” “Dustin didn’t make me do anything that night, or ever,” he wrote. Higgs maintained his innocence throughout.

It was unusual for someone who was not found to have physically carried out a murder to be sentenced to death. But the seemingly unsettled nature of Higgs’s guilt was common. Death sentences often hinge on unverified statements. Capital cases have higher rates of exoneration than any others, and for roughly every eight people executed nationally since 1976, one person on death row has been cleared.

On the evening of Monday, January 11, in the last week of executions, Lisa Montgomery, the fifty-two-year-old woman scheduled to die first, was transported from a federal women’s medical prison in Texas to Terre Haute, where she slept in a room that shared a wall with the execution chamber. Montgomery was severely mentally ill, suffering from psychosis, including hallucinations; dissociative tendencies; and PTSD; as well as brain damage, following a near lifetime of physical and sexual abuse. A series of legal arguments and stays—one regarding her competency—pushed five hours past her originally appointed time, and near midnight, the Supreme Court ruled that the execution could move forward. When asked if she had any last words, Montgomery—who was said by her lawyers to be “extremely dissociative” on the final day of her life—looked bewildered and responded quietly with “No.” She was declared dead at 1:31 am on January 13.

The next day, Corey Johnson, also fifty-two, waited until 10 pm for an answer from the Supreme Court regarding the suffering pentobarbital would cause him—a ruling that would also apply to Higgs. He also awaited a judgment regarding his cognitive capacity. Johnson was intellectually disabled. He had trouble reading and writing, and had tried and failed to pass the GED for twenty years in prison, but he wrote a statement with the help of his spiritual adviser. “I want to say that I am sorry for my crimes. I would have said I was sorry before, but I didn’t know how.” He thanked the prison staff, his spiritual adviser, and his legal team. “To my family,” he wrote, “I have always loved you, and your love has made me real.” The latter words were borrowed from the last book read to him in prison, The Velveteen Rabbit. During the execution, he said that his hands and mouth were burning. He was pronounced dead at 11:34 pm on January 14.

Higgs and Johnson had known each other for years on the row, and they’d been together in A range—a smaller unit for inmates soon to be executed, effectively the runway to the injection chamber. Johnson’s death, for Higgs, was like the loss of a friend and signaled the closing of a door—one of his last ways out.

The next morning, I met with Higgs’s spiritual adviser, Yusuf Nur, in the lobby of the Marriott. Nur was sixty-five, and dressed in a dark suit. We sat down at a small table, and he nodded to a woman behind me—it was Alexa. She looked calm, in black-rimmed glasses, and her nails were a lacquered white. “How is he doing?” she asked. “He is okay,” Nur said. “He is peaceful.” She smiled and thanked him, then excused herself to go up to her room.

Nur and Higgs had met for the first time that morning, after speaking only once on the phone, a few weeks earlier. Higgs had been concerned about infecting Nur with COVID-19, though Nur had already contracted the virus once before at the prison—at the execution of Orlando Hall, in November, where he had served as a spiritual adviser for the first time, and where the guards, notably, had not worn masks. On the morning of the fifteenth, Nur and Higgs had gone over the three prayers included in the Islamic last rites, which would be read in the execution chamber. They were alone together for an hour and a half, separated by glass and speaking through an opening in the barrier between them. (The phones in the room were faulty.) “I don’t think he had any illusions,” Nur said. “He was reconciled.”

The company of a spiritual representative in the final hours before execution has long been considered a First Amendment accommodation, though the specifics of what must be provided have only begun to be litigated in recent years. At the federal level, the adviser, and their presence in the death chamber, is built into the execution protocol. Nur was not a cleric—he had grown up an orphan in Somalia and was now a business professor at a local university. But as Sunnis do not have a clergy, his suitability was attested to by the president of his mosque and approved by the BOP chaplain.

Ministers of religion have always been present in some form on the execution stage, though prior to the twentieth century their attendance supported the state directly, sanctifying the execution, and according to the scholar Stuart Banner, serving to emphasize “the consequences of sin.” As public executions became illegal, beginning in the 1830s—a change propelled in part by a rise in lynch mobs—the role of preachers became that of private counsel, in one sense shifting to the side of the convicted. Faith ministers are still a legitimating presence for the state, though now more as a grace granted the executed, a balm set alongside the injury the state would inflict. Few prisoners reject this sole company they are allowed as they die.

Like many others at Terre Haute, Nur considered his presence there somewhat of a fluke. In November, he had received an email from a Christian pastor, sent to leaders of his mosque, requesting a volunteer adviser for Hall. Nur had waited a week, hoping someone else would step forward.

He was still shaken from Hall’s execution, and cried as we spoke. He described the waiting silence in the moments after the pentobarbital was administered and before it had any visible effect. “I really dread it,” he told me. Later, in February, he referred to this time—after the “poison starts flowing”—saying, “That’s when all the crazy thoughts come to mind. That’s when you think about how it was choreographed, and the role you’re playing.” “You get the impression of a religious sacrifice,” he said. “You’re one of the high priests. They even call you your official designation: I am the ‘Minister of Record.’ ” At the same time, he said, the state created an “illusion of a surgical operation,” and “imitated the hospital room.” Indeed, prisoners were unchained and catheterized before any witnesses arrived. Nur would remind himself that the inmate had asked him to be there. “If he had not asked me, I would not have volunteered,” he said. “But you can’t escape the impression that you’re complicit, that you’re part of their plan.”

At three o’clock, Nur left the hotel for the sheriff’s office. From there, he, Alexa, and two of Higgs’s lawyers would be transported to the prison to wait until the execution.

The afternoon light was now flat and gray, and faint snow fell on and off. I left the hotel and drove south toward the picket at the Dollar General, across the street from the main entrance to the prison complex, where around two dozen protesters were gathering on a strip of grass in front of the store, the same place they’d assembled since the executions had begun in July.

Among the picketers were a handful of former spiritual advisers for prisoners now dead. Bill Breeden, a Unitarian Universalist minister, in navy topcoat and collar, had served at Corey Johnson’s execution the night before. Sister Barbara Battista, from a local Catholic convent, had served at the executions of Keith Nelson, in August, and William LeCroy Jr., in September. Both Breeden and Battista described feelings of culpability akin to Nur’s. Battista, dressed in jeans and a puffy winter coat, was a longtime activist—social justice was a pillar of her order, the Sisters of Providence—and Nelson had reached out to her after seeing her on the news protesting Trump Administration immigration policies.

After Nelson’s death, Battista had learned to ask the executioners for a pillow to be placed under the prisoner’s head, so that he could see the witnesses as he lay on the table. She did so for LeCroy, and when he was dead, she anointed his forehead, lips, chest, and hands, and, she said, “prayed him home to God.” Later, an official who had been in the chamber asked what prayer she had used. It was the Chaplet of Divine Mercy, LeCroy’s request.2

In a 1994 dissent in the case of Callins v. Collins, which upheld the death penalty, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote: “I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.” “The death penalty experiment,” he said, over the preceding twenty years of court endeavors, had “failed.” He connected that failing directly to mortal limits, using the words of another justice, John Harlan II, who wrote in 1971 that the determinations required for deciding who deserved death “appear to be tasks which are beyond present human ability.”

While Nolan believed Higgs was innocent of the specific crime for which he had been sentenced to die, neither Nur nor Nolan found the question of his guilt to matter in the justness of his execution. Both described the penalty as revenge. Nur believed Higgs was “as culpable as the one who pulls the trigger,” but that it was “irrelevant.” “I don’t believe the state has that authority,” he said. “It gave that authority to itself.”

At 2 pm, journalists in Terre Haute received an email: Higgs’s execution had been pushed back, “due to ongoing litigation.” The DOJ’s extraordinary request, and Nolan’s opposition, were moving up to the Supreme Court. We were now asked to report to the prison’s media center at six o’clock.

By six, the sun had set, and the cold was sinking in. The media center was a repurposed staff training facility within the prison compound, in a small, whitewashed building beneath an American flag. Inside, fluorescent lights reflected off beige walls and pine trim, washing the rooms in a dingy yellow.

Scott Taylor, a spokesman for the BOP, briefed the gathered journalists in a carpeted hall, before a glass trophy case seeming to honor former Terre Haute employees. Taylor read a formal welcome and explained our quite limited access to the grounds. Vital to the process, he said, was ensuring the anonymity of the BOP staff. Privacy was a “central concern.” Though not mentioned then, the BOP especially guards the identities of the contracted executioners, who, according to multiple legal filings, have no required training or qualifications, not even for finding a vein.

When we were dismissed, I and several other journalists left the facility. Those who had been deemed witnesses to the execution remained. I was aware of this distinction before my arrival in Terre Haute: very few journalists are allowed to observe executions, and it’s unclear how these determinations are made. Officially, ten members of the media are allowed in the chambers, but during the seven months of executions that maximum was never reached. On the fifteenth, only five were permitted.3 This particular opacity is fitting. Scholars such as Sarat describe the near invisibility of the killings as crucial to their legitimacy.

The media witnesses waited in a room partitioned by a set of glass doors from the official BOP press center and the state’s public-information officers. At the White House at this time, Trump was welcoming the MyPillow founder Michael Lindell and his insurrection notes; Higgs’s clemency petition, received by the president’s office weeks before, was never answered.

At 11 pm, the Supreme Court granted the DOJ’s request, overriding the Fourth Circuit’s stay. Higgs’s execution would move forward. The question disregarded by the court—if it is legal to execute people sentenced in states that have since overturned the penalty—would have likely had bearing on at least six other federal death-row prisoners. Journalists saw the BOP officers through the glass preparing to move. Outside, where a thin layer of snow had settled on car roofs, two white vans started their engines.

Where I was, a mile away, the protesters stepped out into the street. They crossed Prairieton Road, the boundary between their patch of grass and the prison, and stretched yellow caution tape across the compound’s main entry, a drive called West Bureau. They planned to block the media vans there—not knowing the route of the inmate transport, the executioners, or anyone else. Through masks, they called out the names of death-row inmates and the names of their alleged victims. Cops arrived quickly and ripped the tape, the lights of their cruisers flashing red and blue.

In the distance, up the road to the north, two sets of headlights inched along a line of trees: it was the media vans—they were going the back way, down Justice Road. I had the feeling that death had arrived. I left and returned to the press center, where the BOP had locked the doors. I would wait out the execution in my car.

The journalist witnesses waited—in a new set of vans, following a security checkpoint—on the dirt path of Justice Road, halfway to the death house. Alexa and Higgs’s lawyers waited along the same road, in their own van, in the dark, for roughly forty-five minutes. One of the lawyers was crying.

Alexa had seen her brother in person for the first time in twenty years just two days before, as had her son, who had spoken to Higgs often on the phone. Higgs had been shackled at the wrists, hips, legs, and feet, and they could not touch him. “All I could do was just stare at him like I had wanted to,” she told me. “I soaked in everything. . . . Especially all the gray in his beard.” Higgs had stared, too. Finally, he spoke. “You had me thinking you were about three hundred pounds,” he said. “You ain’t even that big.” Alexa laughed.

On the fifteenth, she had been calm for much of the day. But around 3 pm, when the snow began to fall, a new feeling came over her. “I’m really about to watch my brother die,” she thought. “I’m really here to watch my brother die.”

She, Nur, and the lawyers spent eight hours in a classroom at the prison compound. At about 11 pm, one of the lawyers got the call. Nur saw the man’s face fall as he listened. Alexa spoke to her brother at 11:20. “Well, this is it, baby girl,” Higgs said. “Maybe there’s still time,” she told him. “You’ve got something else just coming down the pipeline.” “No,” he said. He had just talked to the lawyers. “That’s what they’re telling me. There’s nothing else.” “I love you,” Alexa said. “I love you more,” he replied.

The death house was surrounded by a fence wrapped in black cloth. A white tent covered the passage attendees traveled from the vans to the entrance. This was to block the view of any potential observer, including, it was said, the inmates whose cells looked northward from the penitentiary. Once inside, it was ten more feet to a door that led directly to the death chamber.

Nur had been delivered to the death house first, and he administered Higgs’s last rites before the others arrived. He recited a chapter of the Qur’an, and the two spoke the Talqeen, a prayer that is supposed to be uttered at the very last moments of a person’s life—words intended to be the last they speak and hear.

Three viewing chambers sat along two sides of the inner room: the victims’ families along the western wall, through one-way viewing glass, and the chambers for the prisoner’s witnesses—family and attorneys—and for journalists, along the southern side, and visible to the prisoner. The chambers reeked of disinfectant and hand sanitizer, of alcohol and aloe. In the journalists’ room, BOP officials had laid out a pad of paper and a few pens. The doors to each chamber were closed and locked from the outside, and the blinds to the main chamber, the death room, were lifted.

Dustin Higgs was lying flat on his back. He was strapped to a gurney by bands across his wrists, ankles, chest, and waist, and his body, beneath a sheet from the neck down, formed the shape of a cross. A heart monitor was attached to his left index finger. One IV line had been inserted in the back of his right hand, and one in a superficial vein in the crook of his left arm. The lines ran into a slot in the green-tiled back wall, behind which was the chemical room, the unseen chamber in which sat the executioner.

Visible in the death room were a U.S. Marshal and two BOP officers, in suits. Nur stood behind a piece of blue tape—this was his mark, the limiting line for spiritual advisers, and he could not cross it. Higgs was three feet away. Above the sink, on a wall next to the officers, was a sign asking all present to wash their hands. All five men wore blue surgical masks.

“Dustin Higgs,” said one of the officers, “you were convicted of numerous offenses, including three counts of premeditated murder and three counts of kidnapping resulting in murder.” He completed the charges, then turned to Higgs and asked if he would like to make a final statement. Higgs remained supine as he spoke. “I’d like to say I’m an innocent man,” he said. “Tamika Black, Tanji Jackson, and Mishann Chinn. I did not kill them and did not order the murders. Tell my family I love them. Be strong. As-salaam alaikum.”

The U.S. Marshal picked up the phone mounted on the wall. “This is the marshal in the execution chamber. Can we proceed?” A pause. “Copy that.” He hung up the phone, then turned to the BOP officials. “There are no impediments.” The sound from the room, piped into the witness chambers through speakers in the ceiling, seemed to falter. At 1 am, the unseen executioner released the pentobarbital into the long silicone lines. Higgs stared at the ceiling. At 1:03, he looked to the left, to his sister. “I love you,” he said. He smiled and gave a thumbs-up with his left hand. Then he looked back to the ceiling again.

Within a minute, his eyes closed. The sound of sobbing filled the chambers, including the execution room. Higgs began to breathe heavily, the action of his chest visible from the witness bays. After some time, his breaths became shallow and soon seemed to stop. After ten minutes more, his eyes partially opened. Another man entered the room, checked for his pulse, and exited. A minute later, the official who had read the charges spoke. “Death has occurred at 1:23 am. This concludes the execution of Dustin Higgs.” Blinds fell across the windows of all three viewing rooms, and the audience dispersed.