The Bobcat Fire burns in the San Gabriel Mountains above Los Angeles, September 17, 2020. All photographs by Kevin Cooley for Harper’s Magazine © The artist/Redux

When I first drafted this essay, almost two years ago, California was on fire. A few months later, Australia ignited. Then the coronavirus hit. By the time I sat down to rewrite the essay last fall, California was on fire again, with three of the four largest wildfires in state history raging simultaneously. The sky above San Francisco turned an unearthly, apocalyptic orange. Sunlight could no longer penetrate the ash, photovoltaic panels stopped working, and the air-quality index in many places exceeded the most polluted cities in Asia, where millions of children have irreversible lung damage. People living in California, Oregon, and Washington State found themselves trapped in their homes. Houses, subdivisions, and entire towns lay in charred ruins. Those who could do so moved their families to safer areas, much as people had done in the early days of the pandemic. As far away as the East Coast, smoke from the fires marred the air, and from where I watched, north of New York City, the evening sun vanished in the haze before it touched the horizon.

Like a spinning wheel that becomes a uniform blur, the relentless pace of unfolding catastrophe is turning into a fixed calendar of disaster that in many places will soon become as regular as the seasons. “Day turns to night as smoke extinguishes all light in the horrifying minutes before the red glow announces the imminence of the inferno,” wrote the Australian novelist Richard Flanagan during the 2019–20 bushfire season. In California, too, the images and stories seemed to belong less to peacetime than to war, and indeed this metaphor has become commonplace in our rhetoric about the climate threat. Al Gore, writing in the New York Times, put it starkly:

This is our generation’s life-or-death challenge. It is Thermopylae, Agincourt, Trafalgar, Lexington and Concord, Dunkirk, Pearl Harbor, the Battle of the Bulge, Midway and Sept. 11.

Similar martial rhetoric weaves through many of today’s decarbonization narratives, from David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth to Saul Griffith’s Rewiring America, and it gives John Kerry’s climate-crisis coalition, World War Zero, its name.

But for all the rhetoric of war, the shape of the metaphor remains fuzzy. If it is simply meant to justify a certain scale of government response—a warlike reallocation of industry, logistical capacity, and spending—it mistakes the true implication of the metaphor and the source of its power. For as the coronavirus has taught us, the credibility of a threat and our sense of responsibility to protect ourselves and others against it can change our behavior in ways we might have thought impossible. What distinguishes a “just” war—that is, a necessary and nonelective war, fought for survival or defense—is that it involves everyone; it is fought by the country, not only the government and not only those who bear arms in combat. It is a source of meaning in addition to anguish.

Smoke from the August Complex Fire envelops San Francisco, September 9, 2020

To those who still harbor doubts about the justness of this war, who continue to question the scientific consensus on global warming and the ravages it promises, I ask only that you entertain, if there is a chance you are right, that there is also a chance you are wrong. Let us even say, for argument’s sake, that the virtual certainty of scientists were reduced to 50 percent confidence and the forecasted effects of climate violence were reduced in severity by 50 percent as well. That would still justify the most massive mobilization of human energy and resources the world has ever seen, because the likely outcome would still be far worse than any threat we have faced in the past.

Of course, there are some who accept the seriousness of the threat but console themselves with the possibility that we might overcome it without serious disruption to our lives. The cost of solar power has fallen by more than 80 percent in the past decade and shows no sign of stopping. Wind power has followed suit. According to reports by the International Renewable Energy Agency and others, wind and solar are now the cheapest forms of energy in most cases, and there are already many places where building new wind and solar capacity is cheaper than continuing to run existing coal plants. Synergistic technologies, such as batteries and electric cars, have improved dramatically over the same period, and there has been progress on more intractable problems such as the decarbonization of air travel and the production of cement, glass, and steel.

But for all the good news, we would be foolish to think technology alone will save us. The fossil-fuel industry will not disappear quietly. Subsidies will not unwind themselves. Legislation to transform our energy system will not enact itself. Politicians must be moved from complicity and intransigence. Minds must be changed. And most crucially, even if we manage in the coming decades to remake our global energy system, we will still need a new form of civic solidarity to deal with the ecological trials headed our way.

That our species has the power to destroy life on earth but not to contain wildfires in California should give us pause as we consider what our ingenuity and determination can do in the face of a violent planet. We can split the atom, construct hydrogen bombs, and send humans to the moon, but that does not mean we can stop tidal waves, prevent ice sheets from melting, or cleanse toxic air. When it comes to arresting fast-moving pandemics, supplying drinking water to eight billion people, or managing refugee flows in the tens of millions, the sheer scale of these problems leaves little hope for after-the-fact technological fixes. The ocean and atmosphere are simply too vast and complex for our minds to finely conceptualize or our tools to fully contain. Our powers are great but narrow, the world far bigger than we imagine.

This sounds grim and it sounds hard. Like you, I have encountered hundreds of versions of this story that cast our unhappy lot in the light of sacrifice and devastation. The crisis is real, and the stakes of inaction are indeed severe, but maybe, for all that, we have gotten the story backward. What if the challenge confronting us isn’t our greatest threat but our greatest opportunity, not a moment of self-denial and self-destruction, but of self-creation and self-discovery? What if, to be more precise, our greatest threat is also our greatest opportunity, because overcoming monumental challenges, when wisdom and heroism are possible, is the great gift of human life, the substance of our proudest moments, and the matter from which ur-meaning is built?

The 2020 presidential election was only the latest milestone on the apparently endless highway of American division. Truth has taken on partisan gradations. Democratic institutions strain and buckle. Norms tremble in the fierce crosswinds of power. We cannot find a way to do even simple things most people agree on: bring down the cost of medications, regulate guns to prevent mass shootings, raise taxes on the rich, or overhaul out-of-date infrastructure. How can we be so far apart when we want so many of the same things? What has gotten so fouled up that vague symbolic fights obscure the irreducible communal basis of our prosperity and strength?

Let me tell a different story about what has gone wrong. Our fundamental affliction is not the magnitude of our problems but our alienation from their manifest solutions. Our tools have never made us more powerful, yet we seem more powerless than ever to effect change. Our primary way of interacting with the world is through a screen, and our principal avenue to changing anything appears to be typing into or clicking on that screen. We are alienated from the earth, from our hands, and from one another. We appear to be part of an efficient system that has brought ever more and cheaper goods to market, but our skills have become specialized to the point of practical uselessness. Our ability to create and cultivate the goods that we rely on and enjoy has shriveled to almost nothing. There is a maddening abstraction to our reality, a virtuality to all life. We are told that we are hopelessly partisan and polarized—patriotic or traitorous, awake to truth or in thrall to lies—but above all we are separate: from one another despite our mutual dependency and from the material reality on which every aspect of our life depends. We are separate from the actions we might undertake, and undertake together, to solve the tangible problems before us, which do not care what brand name or party affiliation their solutions go by. We believe hate is endemic, that we are at one another’s throats, but we don’t know one another. We have never gotten close enough to shake hands, much less see that the throat we mean to grab has wrinkles like our own. We carry the burden of crushing loneliness, and find ourselves isolated from friend and imaginary foe alike. We are trapped in the virtual amber of our paralytic culture, where helplessness and impotence sit on the vine so long they ripen and rot into enmity, vitriol, and rage.

It is a strange irony that climate change has, until recently, had a virtual quality of its own. This is the very essence of what has made it so difficult to combat. The same reason policy disagreements endure for years—that consequences don’t follow actions closely enough to establish irrefutable empirical links—is the same reason our society can recognize the danger posed by a warming planet and do nothing about it for decades. Though nearly every technology in our lives relies on truths (such as electrical or chemical properties) that we apprehend only indirectly, it is in our nature to have a complicated and problematic relationship with the reality—the truth—of our abstract knowledge.

But now climate violence is emerging from the shadows. It is setting fire to forests we can see, scattering the air we breathe with ash, and filling city streets with water. It has begun marching on our offscreen terrain. The past few decades have been what the French call the drôle de guerre, the period after war is declared and before real fighting begins. Except, because what we confront with the climate crisis is war waged on a several-decade delay, the battle started long before the first shots were heard. The challenge of organizing ourselves around this crisis before its worst consequences reach us is no different from the challenge of reclaiming truth from the burning timbers of our smoldering virtual culture—of reknitting a fabric of shared purpose from shared interest. Climate change is the crisis of virtual insouciance stepping terrifyingly into the real.

The more we insist on our separateness and exemption from nature, the more violently nature will educate us otherwise. Where reality gives way to fantasy, politics breaks down; and where politics breaks down, war, revolution, and violence rise up—so Carl von Clausewitz and John F. Kennedy each suggested. If we fail to see the truth of what lies after politics—not the absence of policy, but the presence, the certainty, of violence—we do not bring sufficient determination to the fight to redeem politics. The climate crisis lays this truth bare.

The blessings of war have been obscured by its horrors, no doubt rightly, but we mustn’t confuse the impulse to war for the impulse to violence. It is instead, as many have documented, the impulse to encompassing meaning: lives of purpose, actions of consequence, excitement, comradeship, and responsibility.

In War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, the former war correspondent Chris Hedges notes that, for all its destruction and carnage, war “can give us what we long for in life.” It awakens us to the deadness of the everyday, of life without meaningful struggle and thus meaningful triumph. Even those who have experienced war’s brutality firsthand, he notes, often find themselves disillusioned afterward.

Once again they were, as perhaps we all are, alone, no longer bound by that common sense of struggle, no longer given the opportunity to be noble, heroic, no longer sure what life was about or what it meant.

Sebastian Junger reiterates this point in his book War, in which he chides our culture for lacking the courage to see “that one of the most traumatic things about combat is having to give it up.” Civilian life feels empty by comparison, he writes:

When men say they miss combat, it’s not that they actually miss getting shot at—you’d have to be deranged—it’s that they miss being in a world where everything is important and nothing is taken for granted. They miss being in a world where human relations are entirely governed by whether you can trust the other person with your life.

Junger wrote War after embedding with soldiers in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, one of the war’s deadliest fronts. He talks to soldiers on leave who were desperate to return to the fight. “I got to get back there,” one says. “Those are my boys.” The Army Research Branch has documented cases of wounded soldiers going AWOL to rejoin their units faster, Junger tells us. What keeps drawing “sane, good men” back to combat is not the killing, but “the other side of the equation: protecting. The defense of the tribe is an insanely compelling idea, and once you’ve been exposed to it, there’s almost nothing you’d rather do.”

The flip side of this—removing people from meaningful involvement in the ongoing, communal struggle to live—may be as disaffecting as engagement is compelling. Combat brings latent desires to the surface, desires for purpose, intensity, solidarity, and belonging. These are the very needs that draw young people to tribes of violence and hate, whether neo-Nazi groups or the Islamic State. Gun culture, gang culture, and certain forms of religious fundamentalism traffic in the common intuition that violence is a person’s chief outlet for meaningful action. The persistence of mass shootings and religious massacres confirms that some people do locate agency in this dark place. Many others who do not turn to violence surely suffer the same feeling of disconnection, the sense of having no part in forging the bridges that link the past to the future.

The late anthropologist David Graeber wrote about “bullshit jobs,” the meaningless work that more and more people in advanced societies seem to be doing, and the psychological damage that results from dedicating your life to such labors. But I would go further still and say that when we lose sight of any connection between what we do and what sustains us, an unreality enters our sense of the world. Our conviction that other people are real—that their lives and fates matter irrespective of our own—withers such that we hardly see it go. When we don’t feel that we uphold life, we can’t figure out how to value it. We become, at last, partly unreal to ourselves.

In the foreword to an updated edition of his World War II memoir The Warriors, writing now in the midst of the Vietnam War, the philosopher J. Glenn Gray returned to his earlier intuition that something had gone dreadfully wrong in the contemporary world. His initial feeling had arisen, he believed, from a new kind of total war, one “in which terroristic bombing of cities and civilians became for the first time the rule.” But the significance of this development eluded him until he heard a Japanese philosopher give a talk on the “monstrous character” of modern civilization. The speaker described Japan as having become “the most godless nation of all, with no real motivations other than impulses for material goods and sex.” His lecture focused on the question of whether “men of the East or West can survive without any god or gods.” His explicit answer, Gray tells us, “was an unyielding No.”

Neither the speaker nor Gray, as he wrestled with what our monstrous age had to do with the “attempt to live godlessly,” meant God in the usual religious sense. For Gray, God is the intimation, in the simple words of a soldier in Vietnam who chose to report his unit’s war crimes, that we have “to answer to something, to someone—maybe just to ourselves.” Godlessness is having no one, nothing, to answer to. It is the fundamental abstraction of ourselves from the impact and meaning of our actions.

Far more than the infantry soldier who “occasionally goes berserk,” Gray writes, this abstraction afflicts “the man who kills from a distance and without consciousness of the consequences of his deeds.” The dissociation follows such a man back into civilian life, where an “unconscious depravity” can grow unseen. Gray calls these the “terrifyingly normal” men who “are ever in the vast majority” and “make our age a monstrous one.”

Today, we see such godless abstraction everywhere: in military adventures championed by those who dodged service themselves; in efforts to coax people into debts they have no hope of repaying; in the cynical sale and false marketing of addictive opioids; in the countless disembodied acts companies ask their employees to undertake whose downstream consequences portend the suffering of others. The British writer Dan Gretton uses the term “desk killer” (from the German Schreibtischtäter) to describe this new abstracted manner of presiding over death, and this same dissociation clearly lies at the heart of how we let the climate crisis fester for decades, when inaction ultimately hurts everyone.

Godless abstraction permits situations where what seem to be rational individual decisions ultimately add up to collective madness. There are many examples, but the image from Junger’s book of American soldiers firing Javelin rockets at anticoalition forces in Afghanistan captures it as well as anything. One Javelin round costs $80,000, and Junger marvels at “the idea that it’s fired by a guy who doesn’t make that in a year at a guy who doesn’t make that in a lifetime.” Rocket after rocket goes off, eighty grand a pop. Meanwhile, the fighters on both sides have mostly taken to the battlefield for lack of economic opportunities elsewhere.

Does this make any sense? Can you work backward from this apparent insanity to explain how this is a proper use of money or life? It is fundamentally no different from the logic that describes how and why we have filled the air with as much greenhouse gases in the thirty years since we have known the threat they posed as in all the years of human history before then. We have outsourced and deferred mortal costs, when, had we borne them directly, we would have known they were too great. The cost is economic, but at a certain point of vital significance, economic and spiritual costs are no different.

Our godlessness, Gray writes, is our separation from that which constitutes, sustains, and precedes us:

It implies forgetfulness of the encompassing world to which we are so totally bound, both as individuals and as a species. No longer do we feel answerable to this encompassing which is within us, as memory, imagination, and consciousness, or without us as soil and sun and air and water. We are forgetful of the fact that these latter are not simply things of our environment but natural powers and fibres of which we are made and which enable us to be sustained in existence every moment.

What we have gained in efficiency and scale has come, then, at a price invisible to our measures. The price is our alienation, our separation, from the struggles and triumphs of continuing to live.

A thesis that informs my argument is the belief that the certainty of death, and our efforts to resist and postpone it, are what permit meaning in life. It follows from this thesis that obscuring our relation to this certainty obscures the true stakes and significance of living. The parents who believe that it should not be their child who fights in a war, or their child who forgoes some special advantage, or their child who opts out of today’s careerism at the call of conscience, is no different from the politician or pundit who tells us we cannot “afford” to act on climate change. Generalized and applied to society at large, these self-exempting principles make us weaker, poorer, and more likely to die. For fear of death, they teach us, we cannot afford to protect life.

In the same way, by paying rhetorical homage only to the suffering that climate violence is sure to bring, and neglecting, as perhaps in bad taste, the potential promise in a fight we can’t avoid, we perpetuate a form of the dishonesty that got us here. This is the belief that how we talk about something—whether guided by ideological or moralistic convictions—affects its underlying reality: that by insistence we can freight the unconscious world with our moral schemas. But nature is dispassionate, and we are not being punished. No amount of atonement or misgiving makes any difference. We have a practical crisis on our hands, and it is the first truly universal project in which all of us—all living things—are on the same side.

One promise in this fight—if we address it with the pragmatic clarity one needs in a war—is that it will force us to learn exactly how we relate to the world beyond us and how irrelevant the ego’s preferred myths are to achieving anything tangible. At its best, war has been a tonic that disabuses such idle myths: simplistic equations, for example, about how competitiveness, self-reliance, and self-gratification redound to prosperity, strength, and happiness. Nowhere does war root out more misguided thinking than in the realm of economics, since of all the things whose costs we are told we can’t afford, the expensive diversion of human and industrial capacity to the project of explicit destruction would seem to be first in its class. But going to war rests on the argument that forgoing its expense would be more costly still.

In this way, war helps put the economics of fighting climate change in perspective. It reminds us that words such as “cost” and “afford,” when applied to society as a whole, do not describe objective conditions but rather implicit arguments about how we should expend our energy and resources: which activities and investments today are going to be worth it in the long run.

The preservation of life would seem to be a no-brainer, yet even in the years leading up to America’s entrance into World War II, when the threat posed by a fully mobilized Germany and Japan was clear, the Roosevelt Administration had trouble securing the modest appropriations it sought. Members of Congress, pundits, and other political figures inveighed against the cost and practical impossibility of the war mobilization. When Roosevelt announced that he would like to see the nation producing fifty thousand warplanes a year, Charles Lindbergh dismissed the figure as “hysterical chatter.” To many, he had a point. According to Arthur Herman’s book Freedom’s Forge, aircraft manufacturers in 1938 were supplying the U.S. military with only about ninety planes a month.

Across virtually every industry, as Herman’s book details, the intended expansion of military capacity and the time frame expected to achieve it appeared impossible, and yet, despite all manner of opposition, naysaying, and bureaucratic headwind, the targets were routinely met and exceeded. The production of tanks, in one instance, went from thirteen to more than a thousand per month. Mammoth shipbuilding endeavors sprang up in mudflats and marshes, and new industries, such as synthetic rubber, went from producing virtually nothing to hundreds of thousands of tons of material. The vast majority of these initiatives ratcheted up to full capacity in only eighteen months.

Herman tells the story of how the private and public sectors worked together through the war years to create an “arsenal of democracy.” In three years, beginning effectively from a standing start, the industrial capacity of the nation would overtake that of the Axis powers and go on to produce two thirds of all the military equipment used by the Allies. The war created more than half a million new American businesses, Herman writes, while simultaneously jolting thousands of existing businesses out of the doldrums of the Depression.

The ultimate outlay required of the United States would top $300 billion. Consider that in 1939, U.S. defense spending eclipsed $1 billion for the first time since 1918. The difficulty in funding the mobilization reflected the belief among politicians that such expenditures could not be afforded, or else, after a decade-long depression, could be put to better use. But this wartime spending—deficit spending that as a percentage of GDP exceeded anything before or since—underwrote a booming economy that grew, for certain years of the war, in excess of 17 percent and nearly doubled from the start of the war to its end. Not only did the United States emerge from the war anything but crippled with debt—the growth and shared prosperity the country experienced in the subsequent decades would prove unparalleled.

No one, looking back, would say that the need to confront Germany and Japan did not justify the immense redeployment of resources. The same logic of downside risk applies every bit as much to climate violence. But the larger point is that we emerged from the war years not just better off because a dangerous enemy had been defeated, but better off in absolute terms.

This should give pause to critics of climate action who continue to invoke its cost. It is hard to see how a revolution in technologies that promise limitless clean energy could fail to underwrite the next chapter of human prosperity. Wartime research and development returned extraordinary dividends in postwar technologies, and consistently high spending on forward-looking research during the Cold War repaid the investment handsomely, resulting in the internet, satellites, cell phones, and GPS technology. Clean energy would be no different.

These are the benefits: revolutionary technologies, new industries and jobs, an industrial age founded on the promise of meaningful work. What happens if we consider the cost of inaction?

The price of a warming planet is hard to quantify precisely, since it involves accounting for compounding factors and assigning monetary value to human life. Nonetheless, even conservative estimates are high, cleaving whole percentage points and hundreds of billions of dollars from annual growth. One study concluded that the costs associated with 3.7 degrees of warming—extreme heat, drought, water stress, flooding, reductions in crop yield, increased exposure to malaria and dengue fever, and sea-level rise—would be $551 trillion worldwide. That is substantially more than the global wealth that currently exists. The 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, California, affected a large but fairly sparsely populated area (0.006 percent of total U.S. land) and still managed to cause more than $16 billion in damage, twice the annual budget of the EPA.

Regardless of how one estimates the financial burden of massive refugee flows, failing cropland, lost coastline, disease, and crippling storms, the cost of taking mitigating steps today pales in comparison. The current price of insurance, in other words, is cheap. The problem is that no person, company, or nation can take out a policy on its own. We have to go in on it together or it won’t work.

How expensive is too expensive? When we are talking about deaths in the hundreds of millions and damages in the trillions, one could argue that there is no price too great. It takes capital to plant crops in the spring, after all, but there is no price at which we could afford not to produce food. Having a habitable planet is no different, and what we avoid paying today, with claims that we can’t afford it, may make the future wholly unaffordable, no matter how much we have saved.

Consider drinking water. In many countries water is currently plentiful and cheap. But if water grew scarce, there is no limit to how expensive it could become, since without water a person quickly dies. At a certain degree of scarcity, there is no price you can pay for water, since it is in no one’s interest to sell. Likewise, if grain became scarce enough, a wheelbarrow of cash would be insufficient to buy a loaf of bread. What does it mean, then, to have saved money years before?

The way we talk about saving and spending leaves out the fact that what people and countries save and spend today affects the availability of things in the future. As we all know, the ultimate supplier of everything we use is the planet, and the earth cannot be bribed or cajoled at any price. Money means nothing to it, since it knows money isn’t real.

The more climate change turns the earth into a desert island, the more we will learn that wealth can be lost, permanently. It does not conserve itself like energy or momentum, and it cannot always be turned into the things we want if the things we want are too hard to come by. Humans are ingenious and adaptable, but they aren’t magicians: They can’t reap, mine, or harvest what doesn’t exist. If our foundation corrodes—if it falls away into the sea—we will simply lose all the wealth it props up, hoarding gold coins and paper bills until that is all we have left to build with, write on, eat, and drink.

In 1945, the chairman of the War Production Board wrote a report called Wartime Production Achievements and the Reconversion Outlook in which he compared the U.S. economy of 1939 with that of 1944. Manufacturing volume in the country nearly tripled over this period. The production of raw materials went up by 60 percent. During the initial building boom, new construction more than doubled, and despite millions of working-age men entering military service, the labor force and civilian employment both expanded, with manufacturing employment rising by 60 percent.

The most surprising finding, however, was that while resources were flooding into the war effort, consumer expenditures in the United States actually increased. As the report puts it, “the munitions production which defeated the Axis all came out of additions to the country’s output.” In other words, those who argued that the massive spending required for the war would impoverish us had it exactly backward. We got richer—not only after the war, but during it.

The mythos of thrift and sacrifice on the home front—of victory gardens and scrap-metal drives—largely celebrates symbolic, rather than practical, initiatives. These efforts were not materially but spiritually essential. Asking a contribution of each individual was a way of binding the civic body in a shared endeavor. What was framed as a sacrifice was really a gift—the gift of a purpose, a role, something to do.

Today, the impulse to extend the metaphor of war to the climate crisis seems to assume that war motivates sacrifice, but there are inaccuracies in this assumption, and by focusing on sacrifice, climate-action advocates end up framing their argument in the same terms as their opponents. Sacrifice suggests forgoing what you are entitled to or would otherwise want, but not all forms of giving constitute sacrifice. Giving in the sense of helping, sharing, protecting, or teaching is enlarging, not diminishing. It forges stronger relationships, infuses purpose in one’s actions, and affirms the deepest seat of worth a person can possess: having something to contribute that matters to other people.

John F. Kennedy’s famous exhortation—“Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country”—is stirring and profound because it recognizes that being asked to give affirms dignity and worth, whereas being encouraged to take, consume, or hoard sells you a vision of your own worthlessness wrapped in a flimsy tissue of momentary, misguided hope. This hope is for connection to others and a way out of loneliness, emptiness, or boredom. Consumption betrays our hope not only because inanimate objects can’t fulfill this longing for connection, but also because transaction teaches us that we have nothing to give but money and are therefore meaningless and interchangeable as individuals. It establishes only the weakest form of human relationship, making our connection to others seem remote and insecure, and ultimately deepening the loneliness it was meant to relieve.

We are currently suffering an epidemic of loneliness in the United States, where studies have found that social isolation is more lethal than obesity or smoking fifteen cigarettes a day. The number of suicides in the country has gone up nearly 50 percent since 2006, and rates of suicide and depression among young people aged ten to twenty-four jumped roughly 60 percent between 2007 and 2017. Life expectancy has fallen in recent years, as the opioid crisis has claimed hundreds of thousands of victims and Americans have succumbed to so-called deaths of despair. We are at the same time facing a form of polarization that regiments different identity facets into what the political scientist Lilliana Mason calls “mega-identities.” There are fewer points of contact and shared beliefs among broad swaths of the population.

The types of disconnection behind these trends—interpersonal isolation, national division, the febrile aloneness of screen life and social media, work abstracted from tangible purpose—will end in crisis if a more pressing one does not first drive us back into one another’s arms. It is a type of decadence to indulge so much division when collaboration and solidarity are the basis of our power and plenty. It is likewise a mark of temporary privilege that we have let fantasy contaminate our shared truth. If we cannot rid ourselves of this decadence and privilege, the inexorable reality of climate violence will do so for us.

Why not then address this problem head-on? Why not seize the opportunity to stimulate our economy, rebuild our nation, take meaningful action, and come together in common purpose? At a time of declining productivity, crumbling infrastructure, widening social division, and insecure and often meaningless jobs, to turn away from this bright future and instead toward pessimism and apathy is a sign of cultural depression. We are caught in a vicious cycle, where our social illness robs us of the energy and will to do what is necessary to recover.

Can a fight to rebuild and protect our land from a violent climate shake us out of this despair? War has lost its luster, but in seeking to suffocate the martial enthusiasm that swept countries into battle in the past, we appear to have abandoned the language of national adventure and mythic heroism that vast communal projects require. For all its ills, war has at times galvanized social bodies that were liable to dissipate and fray on their own. What we must do now is find a constructive shared endeavor that unites us without promoting what is heinous about war.

If such a thing exists, the climate fight—the first comprehensive global challenge—would seem to be it. History has then put before us the adversity in which the steel of the soul is forged. It has given us an opportunity to tell our children and grandchildren that instead of bickering and nursing narcissistic grudges, instead of basking idly in our ephemeral plenty, we acted with grit and resolve.

In mobilizing, we may find that what seems a burden turns out to be a blessing. Common struggle holds great riches and satisfaction. Giving—having something to give—is more meaningful than hiding out in fortresses of grievance. We have lived too long in an online dreamworld, and it has made us overly enamored of our feelings and beliefs. What we give will be measured in humility and restraint, in valuing people for what they do rather than for what they merely think.

What I am describing will not always be pleasant, but it promises something much greater than our current loneliness, helplessness, rage, and division. It promises to free us from our certainty and from the wounded righteousness consuming us. It promises to let us see one another and be seen. It offers us the chance to work together, build something, and take the first timid steps back toward trust.

If we fail to mobilize now, we may never have another chance. The notion of a single ungodly disaster that finally spurs us to action and compels the government to respond is a fantasy. If it comes, it will be too late. We will not be individually prepared, and we will expect the government to take charge. We will find ourselves helpless and subject to larger forces, natural and human, on all sides. We will, in short, let the crisis go to waste.

Instead, we must act now, renewing civic vigor and restoring the social institutions that enfranchise us and build community. More concretely, we should establish a national jobs program focused on the climate fight, pulling back from a volunteer (and increasingly privatized) military, and deepen our global outreach. The nation building we have asked the military to perform belongs more properly to noncombat missions such as the Peace Corps. As the conservationist Joe Walston has noted, significant battles in the climate fight will play out in places like sub-Saharan Africa, and the results will depend in part on whether countries in the region urbanize effectively and succeed in educating girls.

Other endeavors should include everything from computer modeling to ocean farming. Overhauling the world’s industrial and energy systems will demand a massive amount of labor. The climate fight will draw on the tangible skills of builders, ecologists, technologists, electrical engineers, agriculturalists, nurses, emergency medical personnel, firefighters, pilots, conservationists, urban planners, and countless others. Whether it is learning to grow our food, fortify our houses, treat injuries, or build communities of mutual support, we may find that the challenges of a world remade by climate change are sources of profound meaning and fulfillment.

But how we move from admiring the problem to organizing around it is not a trivial issue; it is the central challenge in this battle. We need the leadership of those who have experience building and directing coalitions, from union organizers and military veterans to activists and campaign managers. The research of the political scientist Erica Chenoweth shows that nonviolent protests involving just 3.5 percent of a population have reliably brought down recalcitrant regimes. It doesn’t take much for popular will to overwhelm the apparent, but secretly precarious, authority of political, military, and business elites. To this end, we must consider civil disobedience and strikes. Students should walk out of class, and we must pressure companies from within (as employees) and without (as consumers) to act as responsible stewards of the future. There are endless points of leverage because everything and everyone is relevant.

The tide could turn more quickly than people think. In World War II, it took only eighteen months to retool American industry into an unprecedented arsenal. The U.S. military today, unlike so much of the government that funds it, recognizes climate change for the existential threat it is, and the tight margins that make corporations so resistant to change also make them profoundly susceptible to pressure. But we have scarcely begun to mobilize. We are simply not acting as though we are at war.

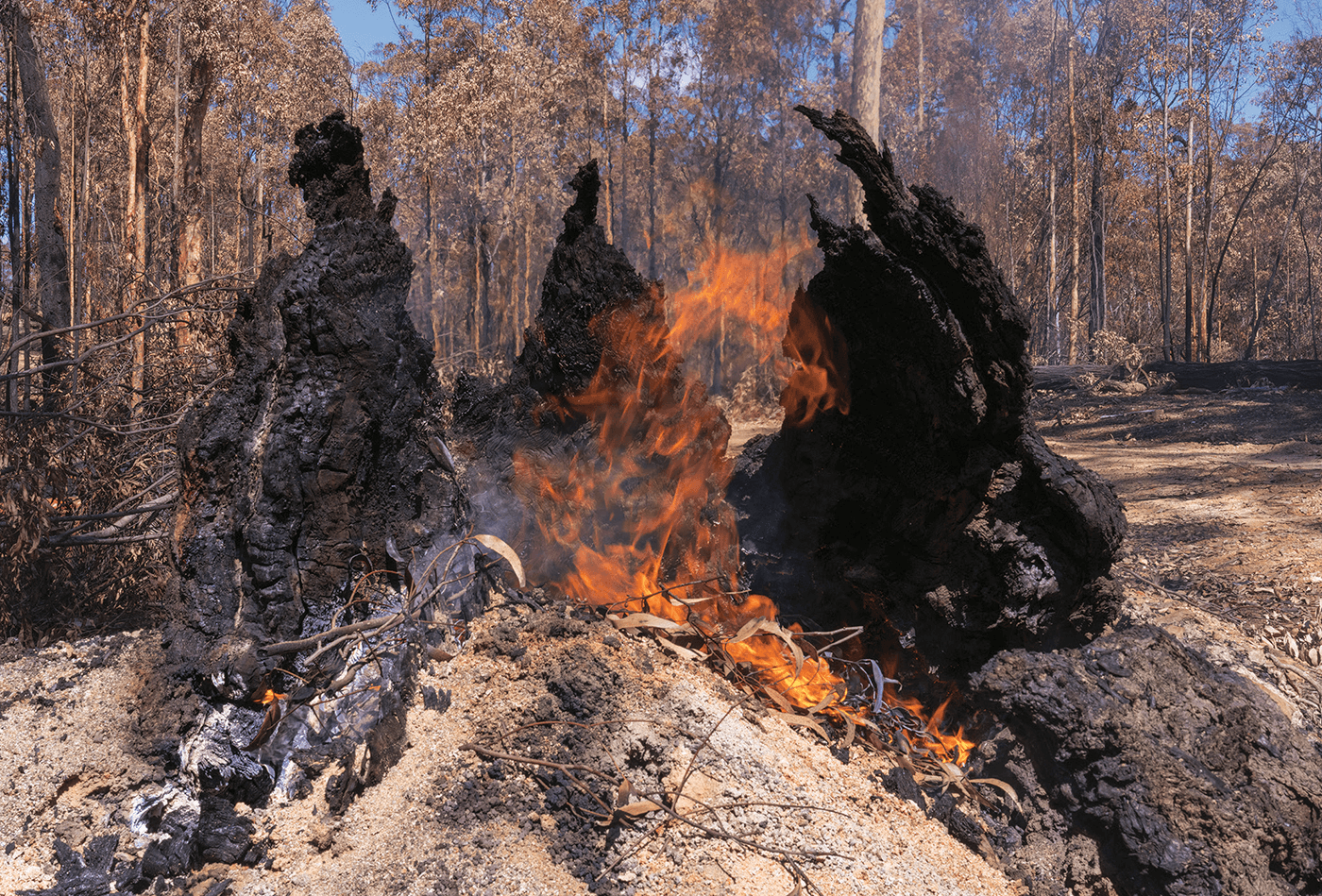

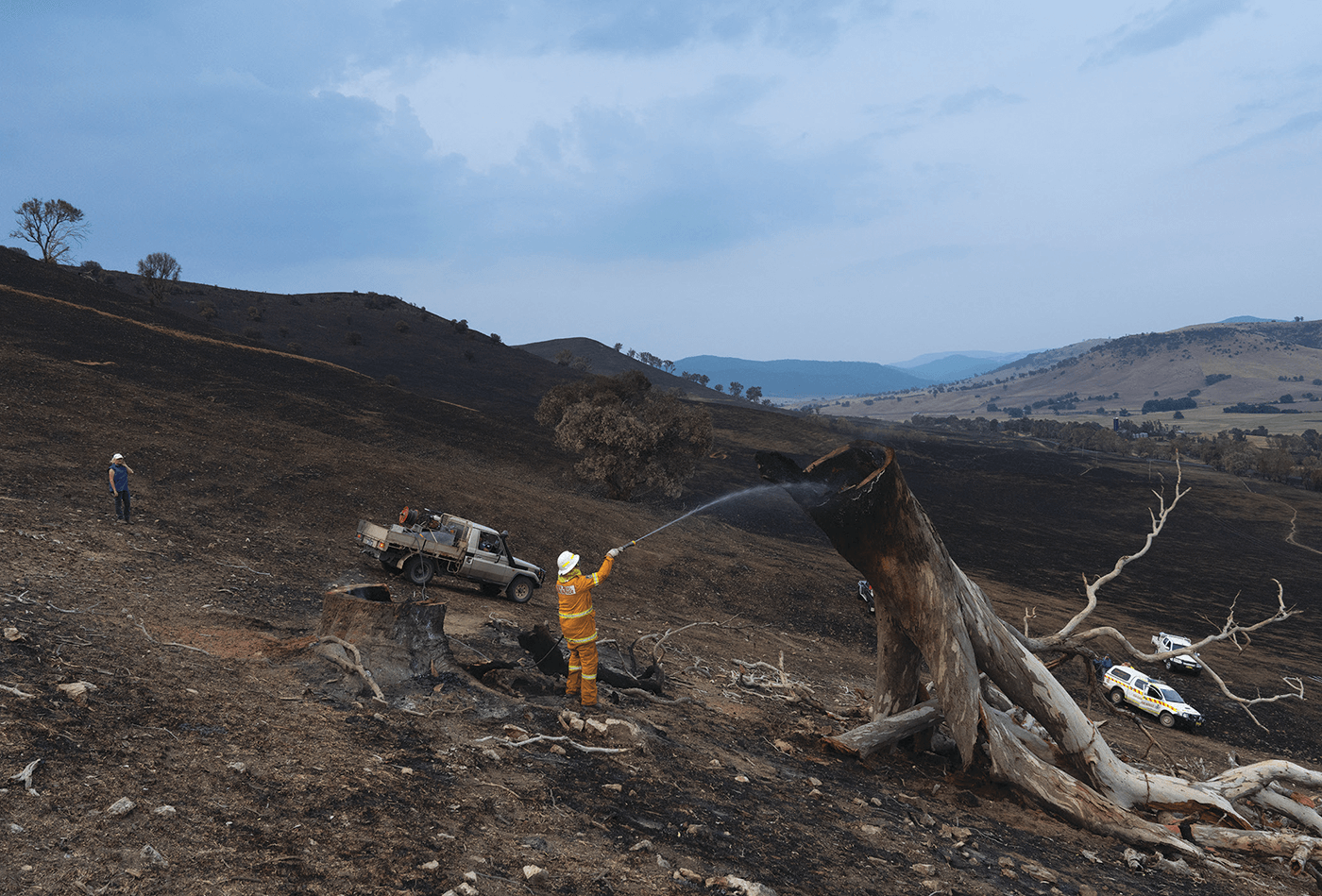

McKenzies Beach, Australia, after the Clyde Mountain Fire passed through, January 21, 2020

The technical capacity to solve our problems exists; the political will does not. Every month that we delay, the problem gets worse. The longer we drag our feet, the less we stand to gain and the more we impoverish our future selves. The climate crisis is a test we are not guaranteed to pass. Can we change? Can we speak, relate, and think differently? Can we put aside our differences and resist the seductions of cynicism and moralism? Ironically, the instinct behind the tribalism that is tearing our political culture apart is the drive to band together to protect the group. What has been a political liability could become an asset in a fight that requires solidarity—if only we can channel it toward common threats and away from exaggerated symbolic divisions.

A frequent dream of those who have experienced war is to somehow reap its positive benefits without enduring the crucible of so terrible, destructive, and dehumanizing an experience. Since we cannot avoid the climate fight, we should take advantage of the opportunity it presents to restitch the fabric of communal life and fate. Gray, the philosopher, describes the enlarging capacity of war as arising not from power or victory, but from the awareness of being part of something greater than yourself, subject to larger forces, and connected to people and things beyond you:

The pervasive sense of wonder satisfies us, because we are assured that we are part of this circling world, not divorced from it, or shut up within the walls of the self and delivered over to the insufficiency of the ego.

The most profound costs of addressing climate change will not be financial or physical, but personal and social. If we can summon the courage to act, we will discover that these costs are also our most profound rewards. They mark an end to our isolation, alienation, and division. But they ask something of us, something that is difficult because it takes place in private, unrewarded instants: an inner giving, denominated in openness and restraint. We must learn not to covet our power, but mistrust it. Not to lord victory over others, but to show solicitude and modesty in triumph. We must see fortune and success as a responsibility, not a boundless permission to do whatever we please. We must hold fast to conscience while repulsing moralism. We must extend tolerance beyond the narrow confines of advocacy and favor, and see humor—good humor—as the handmaiden of humility.

When the stakes of failing to collaborate are not tangibly before us, it is difficult to value working together. But now the floodwaters are rising, the fires are drawing near. Waiting is its own risk. Take the small leap of opening your mind, your ears, your heart. Do what is hard because what is hard creates the parts of you that are strong. Speak truth and listen. Listen for the storm approaching. Listen for what people do not say or do not know how to say, but which recalls your own longing, fear, graciousness, and hope. You do not have to believe anything to join this fight—just know that underneath the protective layers of personality every person is authentic. Every human being is real. Every body can be burned by fire, choked by ash, drowned by rising waters, as well as cherished, loved, and kept safe by the will to fight, protect, and survive.