Illustrations by Pep Montserrat

Last spring, 155 years after the fall of Richmond, the Confederate capital surrendered again. In April 1865, the capitulation was swift and almost outlandishly theatrical: after learning that Robert E. Lee’s army had withdrawn from nearby Petersburg, the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, and his military guard escaped south under cover of darkness, setting half the city on fire as they fled. Early the next morning, the first Union troops arrived. As Richmond’s black residents celebrated in the streets—joined by more than a few poor whites—the black soldiers at the head of the Union column worked to put out the flames. The embers of a regime dedicated to preserving African slavery were extinguished by hundreds of former slaves. The occupying forces then marched to Davis’s executive mansion and commandeered it as their headquarters.

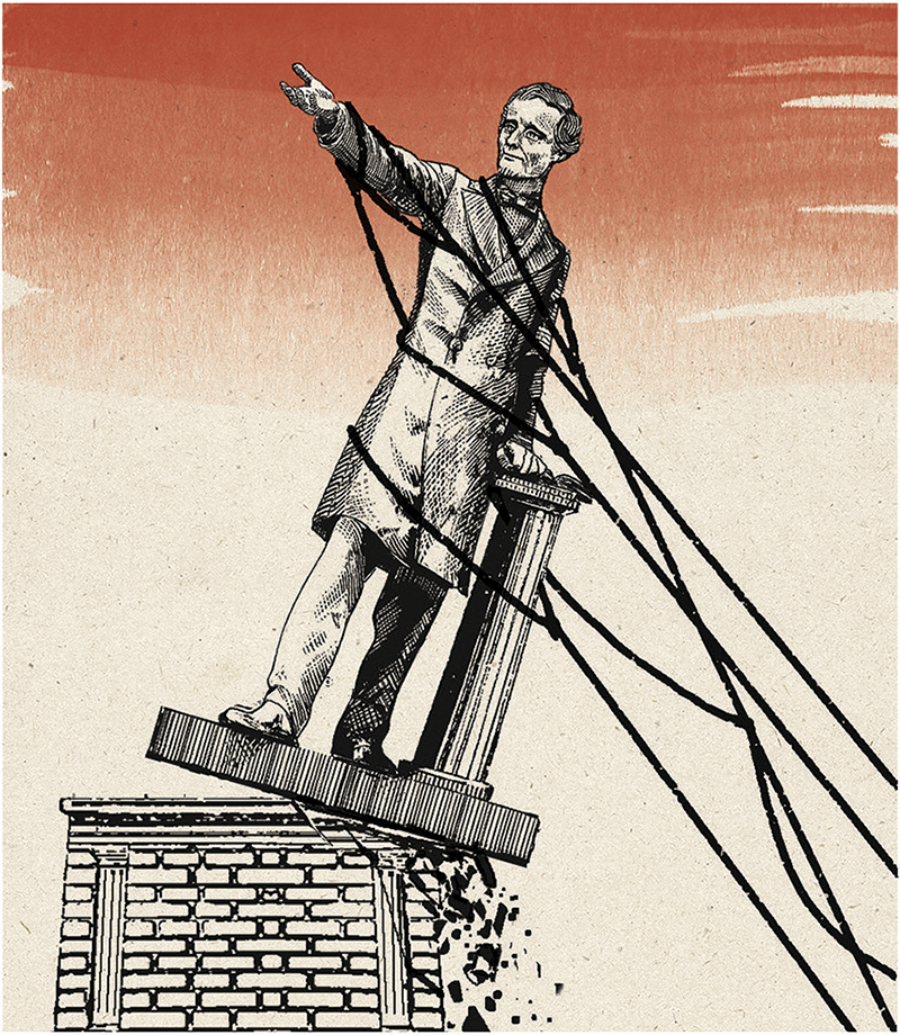

The second fall of Richmond was hardly kinder to the Confederate president. In June of last year, Davis’s eight-foot bronze likeness, which had presided over the city’s Monument Avenue for more than a century, was torn from its pedestal and dumped into the street—his face nullified with black paint, his overcoat spiked with pink and yellow, and his outstretched hand now reaching upward as if making a forlorn appeal to the heavens. In the weeks that followed, Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart, and Matthew Maury, Davis’s bronze company on Monument Avenue—the so-called Champs-Élysées of the South—were likewise eliminated from view, but they at least enjoyed the honor of an official state removal. Davis, their chief, received no such courtesy: protesters tied ropes around his legs and dragged him to the ground with what news reports described as “a tiny sedan.”

The conquest of Monument Avenue represented a key front in the renewed struggle for racial justice: the demand for a dramatic rethinking of U.S. history and its place in public life. Strikingly, the most powerful energy behind this fight comes not only from scholars but from activists, journalists, and other thinkers who have made history a new kind of political priority. Although American historical amnesia is the laziest of tropes—“We learn nothing,” said Gore Vidal, “because we remember nothing”—liberals today are more committed than ever to a passionate remembrance of things past. In recent years, a distinct pattern has emerged. Acts of horror—the killings of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown; the Charleston church massacre; the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia; the murder of George Floyd; the storming of the U.S. Capitol—are met not only with calls for justice but with demands for a more searching examination of history. Reading lists and syllabi are distributed; institutional commissions are tasked with extensive historical inquiries; professional historians appear regularly in op-ed pages, on television, and in social-media feeds.

Every modern political movement makes some contact with history. Even in the United States, with our notoriously weak memory, progressive reformers have always invoked earlier struggles. Eugene Debs boasted that the Socialists of 1908 “are today where the abolitionists were in 1858”; Martin Luther King Jr. never tired of talking about the Declaration of Independence, a beacon of democratic equality whose light exposed how little of it the United States had so far attained. Yet the role of history today, especially within liberal discourse, has changed. Rather than mine the past for usable politics—whether as analogue, inspiration, or warning—thinkers now travel in the opposite direction, from present injustice to historical crime. Current American inequalities, many liberals insist, must be addressed through encounters with the past. Programs of reform or redistribution, no matter how ambitious, can hope to succeed only after the country undergoes a profound “reckoning”—to use the key word of the day—with centuries of racial oppression.

In public debate, this order of operations has produced some unexpected ideological alignments. The Atlantic, a sturdy citadel of centrist thinking on every contemporary subject from populism to Palestine, has been the editorial home of both Ta-Nehisi Coates, this century’s most influential writer on race and U.S. history, and Ibram X. Kendi, the historian who has emerged as this moment’s most prolific critic of American racism. The New York Times, whose editorial board could not muster more than one vote out of thirty for Bernie Sanders, has in the past two years published the 1619 Project, which was billed as “the most ambitious examination of the legacy of slavery ever undertaken” in an American newspaper; an essay making the case for reparations; and an excerpt adapted from Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, which compared America’s “enduring racial hierarchy” with those of ancient India and Nazi Germany.

In the age of Sanders and Trump, the Democratic establishment has assumed a defensive posture, concerned above all with holding off various barbarians at the gate. And yet in its consideration of the past, the same establishment has somehow grown large and courageous, suddenly eager for a galloping revision of all American history. For some left-wing skeptics, this apparent paradox requires little investigation: it redirects real anger toward vague and symbolic grievances. No, the Democrats who govern Virginia will not repeal the state’s anti-union right-to-work law, but yes, by all means, they will make Juneteenth an official holiday. If this movement only signals a shift from material demands to metaphysical “reckonings”—from movement politics to elite culture war—then it is not an advance but a retreat.

This critique, however persuasive as a reading of many liberal politicians, does not do justice to the intellectuals and journalists who have driven the national debate on these issues. It does not quite capture the significance of their interventions, or the ambition of their challenge to traditional liberal ideas. Nor does it capture the peculiarity of today’s politics of history. American conservatives, traditionally attracted to history as an exercise in patrimonial devotion, have in the time of Trump abandoned many of their older pieties, instead oscillating between incoherence and outright nihilism. Liberals, meanwhile, seem to expect more from the past than ever before. Leaving behind the End of History, we have arrived at something like History as End.

The second fall of Richmond marked not only a victory for Black Lives Matter protesters, but a real and significant withdrawal from the lore of the Confederacy, even in ideological precincts where that lore has reigned for more than a century. Last year, Republicans in the Mississippi state legislature voted overwhelmingly to remove the Confederate battle emblem from the state flag; NASCAR broke long-standing tradition and banned the rebel banner from its events; and the pages of right-wing journals such as National Review and The Federalist, often stout defenders of Confederate monuments, now overflowed with conservative authors either questioning or rejecting these symbols. Nearly half of the House Republican caucus, including the minority leader, Kevin McCarthy, and Southerners such as the minority whip, Steve Scalise, and the rising star Dan Crenshaw, voted in favor of a Democratic bill removing all Confederate statues from the U.S. Capitol.

It was not always thus. Barely two decades ago, at a Republican primary debate in South Carolina, George W. Bush defended the state’s right to fly the Confederate battle flag, winning hoots of approval from the audience. Bush’s first attorney general, John Ashcroft, stirred controversy by celebrating “Southern patriots” such as Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson, while his first secretary of the interior, Gale Norton, lamented that advocates of “state sovereignty” had “lost too much” when the Confederacy was defeated. In contrast, the leadership of today’s American right—from congressional Republicans to Tucker Carlson—have used the monuments debate not to defend the traditional virtues of the Confederate Lost Cause, but to denounce related attacks on national figures such as George Washington, Ulysses S. Grant, and Teddy Roosevelt. This is a trumpet blast of retreat, whether liberal commentators have acknowledged it or not.

Donald Trump occasionally staggered forth to celebrate the Confederacy and its icons. But the former president’s fitful bouts of nostalgia had little effect on policy: when his own Department of Defense moved to bar Confederate flags from military property, Trump did not countermand the order. Last summer, Trump loudly opposed a provision in the National Defense Authorization Act mandating the removal of all Confederate names from military property, but his veto was overridden with commanding bipartisan support in both houses of Congress. The White House’s more substantial attempts to develop a politics of history—if they merit such a name—followed the same pattern. As many critics have observed, the so-called 1776 Commission, convened in the dying days of the Trump Administration, was a slapdash affair. Organized as a last-ditch effort to refute “progressive” narratives of history, the commission’s hastily produced report consulted no professional historians, cited no historical scholarship, and recycled huge swaths of text from the authors’ prior publications.

Notably, while the 1776 Report included a range of pseudo-patriotic distortions about slavery and the founding era, it did not attempt to rehabilitate the Lost Cause narrative. It did not even complain that U.S. historians had unfairly neglected Robert E. Lee, as the former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities Lynne Cheney did in her 1994 attack on the Clinton Administration’s National Standards for United States History—a major salvo in an earlier cycle of the history wars. Instead, the report’s authors celebrated Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, praised Reconstruction, and condemned the postbellum South’s descent into Jim Crow, “a system that was hardly better than slavery.” Its genesis notwithstanding, the report’s candid recognition that slavery was the cause of the Civil War and emancipation its result—eschewing hoary tropes about a “brothers’ war”—may well represent an advance from the sentimental politics of Ken Burns’s famous 1990 documentary series. This should not go unnoticed.

Likewise, when the Trump White House announced plans to construct a National Garden of American Heroes as a rebuttal to monument removals, the initial list of statues included Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and the Union Army officer Joshua Chamberlain, but not a single rebel in gray. The final lineup, released as one of Trump’s last presidential acts, ran to 244 “American heroes”—practically anyone ever mentioned in a U.S. history textbook, from Crispus Attucks to Muhammad Ali. The list included zero Confederates.

No doubt a deposit of pro-Confederate feeling remains, in some form, sedimented into the hard edges of the American right. At the U.S. Capitol riot on January 6, a handful of rebel banners were visible in the crowd; one Delaware man, since arrested by the FBI, carried the Confederate colors into the halls of Congress. Yet the occasional appearance of such paraphernalia, however disturbing, is neither new nor surprising: for over a century, after all, the flag has served as America’s most prominent symbol of white supremacy. Its presence at Trump rallies underlines the endurance of racism on the far right, but it does not necessarily portend a resurgence of the Lost Cause, as some have suggested. By any sober accounting, Confederate nostalgia is weaker in the United States today than it was two decades ago.

The right’s most potent energy in the age of Trump has mobilized not around traditional paeans to God, generals, and founders, but an erratic brand of troll humor. So goes Ann Coulter’s viral demand to #CancelYale (because the university is named for the merchant and slave trader Elihu Yale), or the Texas representative Louie Gohmert’s resolution to ban from Congress “any political organization” that has ever “supported slavery” (i.e., the Democratic Party). Even the 1776 Report summoned this spirit, denouncing John C. Calhoun’s racism and then impishly describing him as “the leading forerunner of identity politics.” The goal here is not to develop an alternative right-wing vision of U.S. history, but simply to mock the libs using their own language: conservatism, to update Lionel Trilling, as irritable mental gestures that seek to resemble jokes.

Thus the leading “historian” of the Trump era is the pundit Dinesh D’Souza, who, unlike earlier generations of conservatives, makes no effort to defend or even contextualize slavery, the Confederacy, or Jim Crow. States’ rights play little part in his historical narrative. On the contrary, the central argument of D’Souza’s best-selling books and movies is simply that all these racist evils were perpetuated by “radical” Democrats—men such as Calhoun, Davis, and the Mississippi segregationist James Eastland. Only “conservative” Republicans, from Lincoln to Trump, have faithfully defended American freedom and civil rights.

Left-leaning historians, myself included, have sometimes been tempted to debate this argument, whose particular claims are easily reduced to rubble. But this is a fool’s errand, since D’Souza’s shtick is immune to facts and logic, and frankly indifferent to ideological consistency. You could even say that the D’Souza thesis, widely reproduced in the right-wing media, takes progressive history literally but not seriously. (“Did you know that the Democratic Party defended slavery, started the Civil War, founded the KKK, and fought against every major civil-rights act in U.S. history?” asks one YouTube video produced by the conservative media company PragerU.) This sort of trolling offers no ideological counterblast to the progressive narrative that puts slavery and racial oppression at the center of the American experience. In fact, it essentially ratifies a version of that narrative, claiming the mantle of its heroes, such as Frederick Douglass, and declaring that its villains were the forerunners of Nancy Pelosi and Joe Biden.

Ultimately, this smirking vision of history cannot inspire meaningful conviction. Its emergence reflects a rising breed of right-wing politics that, for all its bluster, does not trouble itself very much about America’s past in the first place. Trump, after all, can barely remember when his supposed heroes were alive, remarking that Andrew Jackson—who died in 1845—“was really angry” about “what was happening with regard to the Civil War.” The macho nationalism of MAGA world, scornful of elite pieties and suspicious of fussy appeals to tradition, does not actually need anything from Jackson, the Civil War, or American history writ large.

Sure, that history contains a healthy store of symbols that may be raided, at will, to serve the ends of present-day political struggles. Thus the same House Republicans who voted to contest the result of the presidential election hours after the Capitol riot could repeatedly appeal to Lincoln and “the better angels of our nature” in defending Trump against impeachment. But such superficialities only dramatize the eclipse of an older style of conservatism, with its filial devotion to the Founding Fathers and its blinkered but sincere odes to universal freedom. If the stuffier school of historical orthodoxy retains any standing in American politics today, it is not within the strongest current of right-wing politics, but with Liz Cheney, Ben Sasse, and the beleaguered cohort of anti-Trump Republicans in Congress.

In this light, the most eloquent Civil War monument of all may be the former president’s own. At the Trump National Golf Club in Virginia, a plaque inscribed with Trump’s name commemorates a gruesome battle: “Many great American soldiers, both of the North and South, died at this spot,” it reads. “The casualties were so great that the water would turn red and thus became known as ‘The River of Blood.’ ” This battle never happened. In 2015, a reporter for the New York Times informed Trump that historians regarded his plaque as a fabrication. “How would they know that?” he responded. “Were they there?”

Today it is not conservatives but liberals who are most sincerely committed to American history. Yet they too have evolved, perhaps even more dramatically, from their ideological forbearers. Great liberal historians from Thomas Babington Macaulay to James M. McPherson are famous for a kind of baseline optimism, expressed in complex accounts of contested and contingent events that ultimately lead to progress. In lesser hands, the liberal narrative can slide toward complacency—or worse, the construction of an American story in which each act of brutality (colonization, slavery, Jim Crow) somehow only sets the stage for the triumphant advance to come (nationhood, emancipation, civil rights). This has been the rhetorical terrain of Democratic presidents since John F. Kennedy, a happy realm where confessed historical crimes painlessly resolve into patriotic triumphs. “There is nothing wrong with America,” Bill Clinton intoned during his first inaugural address, “that cannot be cured by what is right with America.” During the Obama Administration, the reigning bromides echoed Martin Luther King Jr.’s line about “the arc of the moral universe,” in which, as in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, justice is a bit time-consuming but always prevails in the end.

Today’s historicist critics operate within a different kind of cosmology. In her essay introducing the 1619 Project, the journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones notes that black Americans have fought for and achieved “astounding progress,” not only for themselves, but for all Americans. Yet the project does not really explore this compelling story: in fact, it largely skips over the antislavery movement, the Civil War, and the civil-rights era. Strikingly, Frederick Douglass appears more often in the 1776 Report than in the 1619 Project, where he originally received just two brief mentions, both in an essay by Wesley Morris on black music. Martin Luther King Jr., for his part, makes only one appearance in the 1619 Project, the same number as Martin Shkreli. In more than one hundred pages of print, we read about very few major advocates of abolition or labor and civil rights: Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Henry Highland Garnet, A. Philip Randolph, Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, and Bayard Rustin are just a few of those who go unmentioned.

There are many reasons for this. The project aims to do more than curate a Black History Month greatest-hits album. Yet the exclusion of prominent black abolitionists and civil-rights activists also reflects an editorial worldview. For African Americans, Hannah-Jones argues, the depth of historical oppression looms larger than the shallow consolations of progress: “Black people suffered under slavery for 250 years,” she writes. “We have been legally ‘free’ for just 50.” To put black history at the heart of the nation’s story, she and her collaborators insist, is to dispense with the smug fictions of American moral momentum. The timeline assembled in the 1619 Project, which runs from the Middle Passage to Hurricane Katrina, suggests a radical alternative. In place of the liberal narrative of progress—one step back, two steps forward—it conjures American history not as dialectic but as cycle: a rhythmic rotation of white brutality (the Fugitive Slave Act, the Tuskegee experiment, the Birmingham church bombing) and black creativity (Phillis Wheatley, the Sugarhill Gang, Jesse Jackson). But within the turnings of this four-hundred-year-old gyre, there’s little evidence of an arc bending toward justice.

Two fundamental themes anchor the 1619 Project’s approach to American history: origins and continuity. The table of contents is a fusillade of facts that have emerged, in unbroken lines, from centuries of persecution. Whether the subject is Atlanta traffic, sugar consumption, mass incarceration, the wealth gap, weak labor protections, or the power of Wall Street, the burden of argument remains the same: to trace the deep continuities among slavery, Jim Crow, and racial injustice today. “Why doesn’t the United States have universal health care? The answer begins with policies enacted after the Civil War,” one essay posits. “American democracy has never shed an undemocratic assumption present at its founding: that some people are inherently entitled to more power than others,” notes another. The wheel of history spins and spins, but it doesn’t exactly move.

Above all, the historical imagination of the 1619 Project centers on a single moment: the purported date that marks the arrival of African slaves in British North America. “This is sometimes referred to as the country’s original sin,” writes Jake Silverstein, the editor of The New York Times Magazine, “but it is more than that: It is the country’s very origin.” Out of this moment, he continues, “grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional”—the kernel of four hundred years of economic, political, and cultural life. History, in this conception, is not a jagged chronicle of events, struggles, and transformations; it is the blossoming of planted seeds, the flourishing of a foundational premise.

The dominant images here are biblical and biological: slavery as America’s “original sin”; racism as part of “America’s DNA.” (The 1619 Project contains no fewer than seven such references.) These marks are indelible, and they stem from birth. The existence of slavery and racism means that America has been Stamped from the Beginning, as Kendi titled his first book, ironically borrowing a phrase from Jefferson Davis. “Just as DNA is the code of instructions for cell development,” writes Wilkerson, “caste is the operating system for economic, political, and social interaction in the United States from the time of its gestation.” From happy cures and bending arcs to tainted natures and embedded genetic codes, the metaphorical distance between the old liberal history and the new dispensation is immense.

Since its publication, the 1619 Project has attracted criticism from nearly every ideological quarter. On the right, it has become a soft target for politicians in search of a culture war: a handful of Republican legislators have even proposed bills barring the project from classrooms—a clear violation of free speech. On the left, the Trotskyist World Socialist Web Site has denounced it as “a reactionary race-based falsification of American and world history.” (The Communist Party USA, for its part, has defended the project.) But in some ways it is the long-tenured champions of liberal history who have fought it most fiercely. McPherson, Sean Wilentz, and three other scholars of American history have challenged several of the project’s claims—in particular, the way that Hannah-Jones portrayed the link between slavery and the American Revolution. According to her account, “Britain had grown deeply conflicted” about slavery and the slave trade by 1776; by cutting ties with the empire, America’s founders aimed “to ensure that slavery would continue.” “One of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain,” she wrote, “was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.”

Wilentz and other critics argued that this fundamentally misrepresented the politics of the Revolution. As historians from Eric Williams to Christopher Brown have explained in detail, antislavery sentiment in Britain remained marginal in the 1770s. Certainly, it was much weaker in London than in the rebellious colonies, where at least seven colonial assemblies had already attempted to end the importation of enslaved Africans, and where the Continental Congress would ban the slave trade in 1774. As the scholar Leslie Harris put it bluntly in Politico, “The protection of slavery was not one of the main reasons the 13 Colonies went to war.” Harris, who had been contacted by a Times fact-checker to help confirm material in the 1619 Project, wrote that she had “vigorously disputed” Hannah-Jones’s “incorrect statement” and was distressed to see that it had made it into print.

Eventually, the Times issued a thin “clarification,” agreeing to change the phrase “the colonists decided” to “some of the colonists decided,” but leaving the rest of the questionable text in place. Later, the editors deflated some of the most forceful language introducing the project, eliminating one phrase about 1619 as “our true founding” and another sentence that described 1619 as “the moment” when America began. For some critics, these edits represented a major admission of error, and an embarrassment for the Times, yet Silverstein insisted that no real concessions had been made. Revealingly, he noted that the idea of 1619 as America’s “true founding” was always a “metaphor”—a metaphor of national birth—and that its impact was undiminished by the changes.

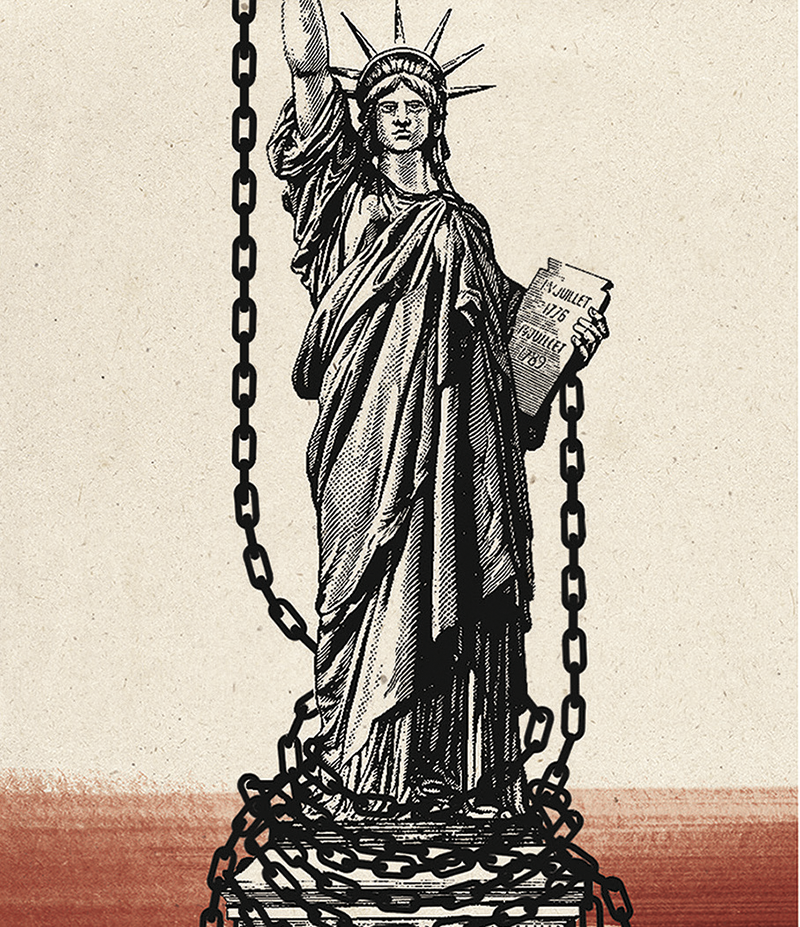

In one sense, Silverstein is right to suggest that the real stakes of the controversy run deeper than any specialist debate about the 1770s. Though Wilentz titled his critique of the project “A Matter of Facts,” framing his analysis as a correction, the debate cannot be resolved by an appeal to scholarly rigor alone. The question, as The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer has written, is not only about the facts, but the politics of the metaphor: “a fundamental disagreement over the trajectory of American society.” In a country that is now wealthier than any society in human history but which still groans under the most grotesque inequalities in the developed world—in health care, housing, criminal justice, and every other dimension of social life—the optimistic liberal narrative put forward by Kennedy and Clinton has ceased to inspire. Some commentators have rushed to declare Joe Biden a transformational president on the basis of his large stimulus bill, but Biden’s chastened brand of liberalism remains less notable for what it proposes than what it removes from the horizon: universal guarantees for health care, jobs, college education, and a living wage. Although Biden may still invoke Obama’s “arc of the moral universe” on occasion, the metaphors that brought him to power, and that still define his political project, are not about the glories of progress but the need for repair: “We must restore the soul of America.” In a country so deeply riven by injustice—with violence and oppression coded into its very DNA—what more could be hoped for?

In this sense, for all their narrative daring, the new cohort of historicists are not only institutionally but ideologically at home with the politics of today’s liberal establishment. The vulgar materialist dimension of this point is relatively clear-cut: unlike an older generation of new-left radicals, figures such as Coates, Hannah-Jones, and Wilkerson sit not at the margins but near the core of the American cultural elite, writing for the nation’s most influential journals, winning its most prestigious prizes, and receiving acclaim from its most powerful politicians, from the Senate majority leader to the vice president. In the past five years, Hannah-Jones has emerged as an outspoken Twitter critic of Sanders and his left-wing class politics.

The ideological alignments go deeper still. As the critics Pankaj Mishra and Hazel Carby have noted, the new style of historicism focuses narrowly, if not exclusively, on the United States, sidelining the much larger history of slavery and racism in the Atlantic world, while ignoring the global impact of the U.S. empire. The result is a kind of funhouse mirror of American exceptionalism, in which many of the familiar heroes—from Jefferson to Lincoln—become villains, but the setting is essentially the same. Likewise, as the political scientist Adolph Reed Jr. has argued, the new historicism either neglects the question of economic class or subordinates it to the politics of racism—producing a reductive and strangely motionless version of the past that the historian James Oakes calls “racial consensus history.” And as the professor Harvey Neptune has pointed out, nearly all of these authors offer an account of race that tends to naturalize rather than historicize its emergence as an ideological category, ignoring more critical work on the production of racism by foundational scholars such as Barbara Fields and Nell Painter.

Beyond these omissions and confusions, there is the basic question of the narrative itself. If one key function of the old liberal history was to fortify belief in the course of incremental progress, what is the political work of the new dispensation, with its metaphors of birth, genetics, and essential nature? How can a history grounded in continuity relate to a politics that demands transformational change? In so many ways, it seems to lead in the opposite direction. There is a reason why Biden, who notoriously promised Democratic donors that “nothing would fundamentally change” if he were elected, has had little trouble adopting the new framing of slavery as America’s “original sin.”

The problems with this metaphor are manifold, as the historian James Goodman has noted: its historical anachronism, its confusion of the sacred and the profane, and its tendency to obscure, rather than clarify, the burden of responsibility for the crime of slavery. Yet perhaps the most serious problem is not the theological question of “sin”—a fair word for racial oppression in America since 1619, and one that has done heroic service in the cause of justice since the era of abolition—but the deceptiveness of “original.”

In 1971, Michel Foucault published a lengthy critique of any enterprise that aimed to attain historical truth by uncovering its elemental beginnings. “History,” he wrote, quoting Nietzsche,

teaches how to laugh at the solemnities of the origin. The lofty origin is no more than “a metaphysical extension which arises from the belief that things are most precious and essential at the moment of birth.”

This is a perverse fantasy, Foucault believed. Actual historical origins were neither beautiful nor ultimately very significant. A true student of the past, he argued, must grapple primarily with “the events of history, its jolts, its surprises, its unsteady victories and unpalatable defeats—the basis of all beginnings, atavisms, and heredities.” Against the idea of either a glorious or a deterministic starting point, Foucault urged an approach to the past that emphasized turbulence over continuity:

History is the concrete body of a development, with its moments of intensity, its lapses, its extended periods of feverish agitation, its fainting spells; and only a metaphysician would seek its soul in the distant ideality of the origin.

Whatever birthday it chooses to commemorate, origins-obsessed history faces a debilitating intellectual problem: it cannot explain historical change. A triumphant celebration of 1776 as the basis of American freedom stumbles right out of the gate—it cannot describe how this splendid new republic quickly became the largest slave society in the Western Hemisphere. A history that draws a straight line forward from 1619, meanwhile, cannot explain how that same American slave society was shattered at the peak of its wealth and power—a process of emancipation whose rapidity, violence, and radicalism have been rivaled only by the Haitian Revolution. This approach to the past, as the scholar Steven Hahn has written, risks becoming a “history without history,” deaf to shifts in power both loud and quiet. Thus it offers no way to understand either the fall of Richmond in 1865 or its symbolic echo in 2020, when an antiracist coalition emerged whose cultural and institutional strength reflects undeniable changes in American society. The 1619 Project may help explain the “forces that led to the election of Donald Trump,” as the Times executive editor Dean Baquet described its mission, but it cannot fathom the forces that led to Trump’s defeat—let alone its own Pulitzer Prize.

The political limits of origins-centered history are just as striking. The theorist Wendy Brown once observed that at the end of the twentieth century liberals and Marxists alike had begun to lose faith in the future. Collectively, she wrote, left-leaning intellectuals had come to reject “a historiography bound to a notion of progress,” but had “coined no political substitute for progressive understandings of where we have come from and where we are going.” This predicament, Brown argued, could only be understood as a kind of trauma, an “ungrievable loss.” On the liberal left, it expressed itself in a new “moralizing discourse” that surrendered the promise of universal emancipation, while replacing a fight for the future with an intense focus on the past. The defining feature of this line of thought, she wrote, was an effort to hold “history responsible, even morally culpable, at the same time as it evinces a disbelief in history as a teleological force.”

Today’s historicism is a fulfillment of that discourse, having migrated from the margins of academia to the heart of the liberal establishment. Progress is dead; the future cannot be believed; all we have left is the past, which must therefore be held responsible for the atrocities of the present. “In order to understand the brutality of American capitalism,” one essay in the 1619 Project avers, “you have to start on the plantation.” Not with Goldman Sachs or Shell Oil, the behemoths of the contemporary order, but with the slaveholders of the seventeenth century. Such a critique of capitalism quickly becomes a prisoner of its own heredity. A more creative historical politics would move in the opposite direction, recognizing that the power of American capitalism does not reside in a genetic code written four hundred years ago. What would it mean, when we look at U.S. history, to follow William James in seeking the fruits, not the roots?

An older tradition of left-wing American politics had much less trouble with this kind of historical thinking. Frederick Douglass plays little part in the 1619 Project, but he knew better than most that historical narratives matter in political struggles: they shape our sense of the terrain under our feet and the horizon in front of us; they frame our vision of what is possible. Douglass’s famous speech about the Fourth of July came at a low ebb of the abolitionist movement, just after the Compromise of 1850, which included the Fugitive Slave Act, appeared to remove the question of slavery from national politics for good. That made it all the more important for him to build an argument from history, drawing on the experience of the Revolution to insist that the United States belonged not to “the timid and the prudent,” but to insurgents who “preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage.” Douglass’s fight against antebellum timidity took courage and purpose from an understanding of history in which radical change was possible.

Moreover, Douglass questioned the wisdom of any historical politics that undermined the prospects for present-day change. This did not imply a purely instrumental contempt for the past, in the manner of the Trumpian right, but rather reflected a clear-eyed determination to treat history not as scripture or DNA, but as a site of struggle. “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future,” Douglass declared. “To all inspiring motives, to noble deeds which can be gained from the past, we are welcome. But now is the time, the important time.” For some scholars, this must read like rank presentism—yet unlike the neo-originalist framing of the 1619 Project, it gets the order of operations right.

The past may live inside the present, but it does not govern our growth. However sordid or sublime, our origins are not our destinies; our daily journey into the future is not fixed by moral arcs or genetic instructions. We must come to see history, as Brown put it, not as “what we dwell in, are propelled by, or are determined by,” but rather as “what we fight over, fight for, and aspire to honor in our practices of justice.” History is not the end; it is only one more battleground where we must meet the vast demands of the ever-living now.