“Boy with June Bug, Fort Scott, Kansas, 1963,” by Gordon Parks © The Gordon Parks Foundation

In the season of picnics, hikes, and naps in the shade, Lucy Jones’s impassioned exhortation Losing Eden (Pantheon, $27) may feel inevitable and hence almost extraneous. And yet her argument is both urgent and complex: humans must rally to save our planet; in doing so, we may also save ourselves; and in order to do so, we must reengage with the natural world and teach our children to do the same. The book cites media reports that three quarters of five- to twelve-year-olds in the United Kingdom now spend less time outdoors than prison inmates, and one suspects statistics in the United States are little different. Jones also reminds us that

in 2007, the words “acorn” and “buttercup” were taken out of the Oxford Children’s Dictionary, in favor of words like “broadband” and “cut and paste” to reflect changing usage of the language. “Hamster,” “heron,” “herring,” “kingfisher,” “lark,” “leopard,” “lobster,” “magpie,” “minnow,” “mussel,” “newt,” “otter,” “ox,” “oyster” and “panther” were also deemed archaic and removed.

We should be appalled at the potential loss of these words from our vocabulary, as we would be at the potential loss of the creatures they name. Words matter, and in this book, Jones conveys in evocative prose the exuberance of her own rediscovery of nature’s wondrousness, a significant component in her recovery from struggles with addiction and depression. Jones writes of visiting a forest school, a form of early education gaining popularity in the United Kingdom, in which kids learn outdoors. This reminds her of her own childhood, when “stopping to observe the perfect rings on a pink worm, or the flicking eye of a lizard, or the matte tusks of a stag beetle was so exciting I felt I would explode.” Of a visit to Svalbard, an archipelago to the north of the Norwegian mainland and home to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, where more than a million samples are protected against the possibility of ecological disaster, she writes,

The light . . . is exquisite: both lucid and hazy, reflected by cream and gold mountains. As the sun moves, the mountains grow ultra-violet pink at their tips and the rest is a pale violet, against the bluest sky. Across the strait, a mountain soars up into a flattened peak, crenellated like the spine of a large dinosaur.

These vivid elements of personal experience are interwoven with factual information drawn from a wide array of sources. Among them are E. O. Wilson’s concept of biophilia (articulated in his 1984 book of the same name), the idea, as Jones writes, that “humans have an innate and emotional affiliation to life, life-like processes and other living organisms”; the recorded evidence that postoperative patients given views of nature from their hospital-room windows experience a stronger recovery; Dacher Keltner’s application of the philosophical concept of awe to scientific study; and the revelation that people behave more generously toward one another after encountering scenes of the natural world. Countless psychological and sociological studies confirm the health benefits of interacting with nature—it has been shown to reduce stress as well as alleviate certain symptoms of ADHD. We, too, are animals, after all.

Jones devotes a chapter to the University of Glasgow professor Richard Mitchell’s concept of equigenesis, which suggests that “a connection with nature might actually reduce the health gap between rich and poor and lead to a better, more equal society.” As Jones writes, “nature is not a luxury,” and access is essential; yet a report by the National Park Service in the United States showed that African Americans composed only 11 percent of visitors in 2018. As the writer Latria Graham has observed, “People of color are still often left out of the conservation decisions and planning that affect their communities.”

Jones’s compelling and wide-ranging investigation—marred only by a prologue and an epilogue that feel too cute—is, inevitably, replete with upsetting information about the gross neglect of our environment. But there is more hope than despair, not least in Jones’s illumination of the places where efforts at repair are under way—in Detroit’s more than 1,900 community gardens and small farms; in Singapore’s “green rooftops, green walls, green balconies and vertical gardens”; in the United Nations’ 2015 recognition of the principles of earth jurisprudence. We’re running out of time, as we well know, and in some measure Jones’s admirable synthesis of research serves chiefly to insist, passionately, on the paramount importance of the earth’s well-being. She appeals to the child in each of us to rekindle our sense of awe at the natural world:

There is an abundance of wonder in our home that we are losing as habitats shrink and our connection wanes. Antlers. Orcas. Seastars. Stag beetles. Curlews. Rotifers. Toadstools. Glow worms. Puffins. Bats. Chrysalides. Shooting stars. Red velvet mites. The rosy maple moth. Christmas tree worms. The bioluminescent strawberry squid. Pygmy shrews. Wolves. Crows. Opals. Nudibranchs. Owls.

To name but a few.

“Roma, 1995,” by Olivo Barbieri © The artist. Courtesy Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York City

Gianfranco Calligarich’s Last Summer in the City (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $26)—newly available in English almost fifty years after its initial publication, with an engaging introduction by André Aciman and elegantly translated from the Italian by Howard Curtis—evokes experiences that could be characterized as the opposite of wonder. Leo Gazzara, the novel’s protagonist, drifts in a haze of jaded anomie during a summer in Rome punctuated chiefly by his obsession with the emotionally elusive Arianna and his efforts to curtail his excessive drinking. First published in 1973, Last Summer in the City has the languorous disaffection of the mid-twentieth century, offering a touch of Francoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse (a privileged idyll imperiled by tragedy), but chiefly reminiscent of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Godard’s Breathless, films in which cities—Rome and Paris, respectively—are themselves primary characters. “Rome by her very nature has a particular intoxication that wipes out memory,” Gazzara reflects at the novel’s outset.

She’s not so much a city as a wild beast hidden in some secret part of you. There can be no half measures with her, either she’s the love of your life or you have to leave her, because that’s what the tender beast demands, to be loved.

Both the pleasures and the limitations of Calligarich’s novel are conveyed here: it is at once bombastic and melodramatic, simultaneously passionate and ironic, thoroughly enjoyable and very much of its time. When Gazzara and Arianna visit the Forum at night, she says, “It’s stupid . . . feeling nostalgic for something we never had,” a comment that is kind of great and kind of ridiculous at the same time. They then have a conversation about the pleasures of reading secondhand books, and about how “books make different impressions according to the state of mind you read them in,” an observation of course both true and satisfying.

The novel is accented with oblique romantic banter, inflected by soul-searching and artistic pretension; it unfolds in a drifting season of parties, café conversations, and illicit swims on the docks of empty villas. Work recurs as a periodic, irritating intrusion (Gazzara, a newspaper journalist, makes a brief, ill-fated foray into television); friends and acquaintances lurch in and out of view. An unforeseen death will alter the tenor of the narrative irrevocably.

Arianna remains a cipher, a beauty whose actions are simultaneously disingenuous and hard to parse: Gazzara’s obsession with her is prompted by that cool unknowability. A contemporary reader feels at once the romantic pleasure of their unsettled and opaque dance and—let’s be honest—a sense that Arianna, though thinly drawn, is either dumb as a rock or tediously manipulative, possibly both, while Gazzara is a fool, willfully duped by his own projection and lust.

The novel, like the films that it recalls, offers a seductive, stylized fantasy of life; but one that, before the advent of the internet, had real resonance. Once upon a time, people did drift in youth, their hours unaccounted for, wandering through cities and conversations. Lacunae in communication—e.g., simply not knowing where someone was at any given moment, and having no way to locate them—made life a sea of uncertainty and generated intense, untethered emotion. For those of us old enough to recall such aimless, yearning days, the novel is moving in spite of its silliness. For those who’ve known only the tyranny of the present, the novel may make them, as Arianna puts it in an aforementioned passage, “nostalgic for something we never had.”

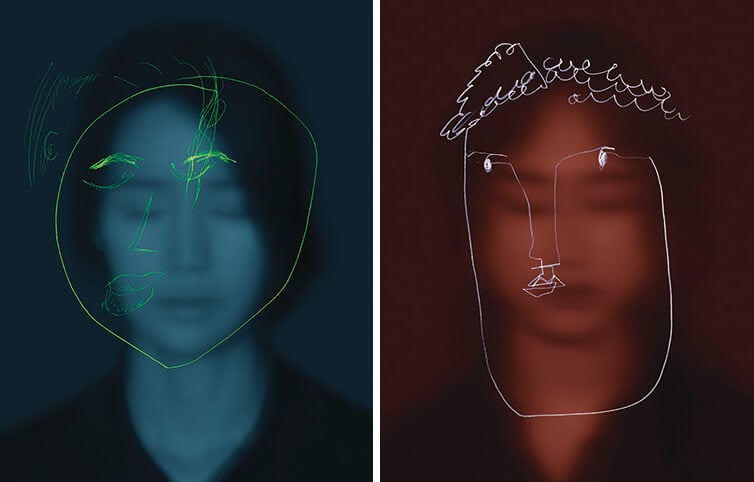

“Face of Face 5” and “Face of Face 2,” by Kyungwoo Chun. Courtesy Bernhard Knaus Fine Art, Frankfurt, Germany

The impossibility of fully knowing someone else, or indeed oneself (the inevitable lacunae!), is an eternal theme of fiction, framed in infinite ways. The immigrant experience, in which multicultural characters necessarily navigate these gaps, is one such frame, and Yoon Choi’s beautiful debut story collection Skinship (Knopf, $26) uses it to bring a rich and engaging new voice to contemporary American letters. With refreshing amplitude, patience, and (dare I say) wisdom, Choi’s stories explore the complexities of her characters’ diverse experiences. She conveys with equal authority the rueful reflections of a childless middle-aged woman contemplating her youthful choices (“The Church of Abundant Life”); an idiosyncratic, isolated former piano prodigy’s excitement and confusion at encountering his classmate from the conservatory, along with her daughter (“Solo Works for Piano”); a woman’s recollection of her arrival in the United States, with her mother and brother, having secretly fled her father (“Skinship”); and the intermittently dreamlike experiences of a grandfather with dementia trying to care for his grandson (“The Art of Losing”).

In each story, Choi evokes a world entire, an endeavor that extends beyond content into form. In “First Language,” which is told in the first person by a Korean immigrant with imperfect English (“All that afternoon, I had the trouble in my heart. I knew that my mother felt the same thing because we would not match eyes”), we come to understand that the chasms of language and culture have led to an agonizing situation. As a schoolgirl, Sae-ri, the narrator, was seduced by a teacher and gave birth to a son, Min-soo, out of wedlock. Big Mother, her aunt, seeks to remedy the situation by arranging a marriage for Sae-ri to James, a thirty-five-year-old bachelor in the United States. Big Mother tells Sae-ri that James is aware of Min-soo, but understands that Sae-ri is a widow and that the boy will be raised by his paternal grandparents, when in fact he is to stay with Sae-ri’s family. In fact, James has not been told about Min-soo at all. The story, narrated thirteen years after these events, is about the long aftermath: Sae-ri and James have two daughters, Emily and Elena, but they are also raising, belatedly and with difficulty, Min-soo, who has been sent to the Second Chance Ranch, a facility for difficult boys, from which he is being expelled. What was literally lost in translation has ongoing consequences. “I try to be honest, really honest, to myself, but it is not so easy. I don’t know where is the beginning of the lie and where is the end. I will tell you something,” Sae-ri confides to the reader. “It is very easy to lie in the language that is not your first language.”

This simple observation is the opposite of bombast: at once ordinary and profound, it ripples outward to evoke the biggest questions of identity and meaning. If we are made of words, made in words, and then transplanted to another language, another world, who do we become? What might it mean, in such circumstances, to be truthful, or authentic? In his American life, Min-soo, from whom Sae-ri was separated for five years, is renamed Matthew: Are Min-soo and Matthew the same, or different? At the story’s end, Sae-ri insults her son first in English, then in transliterated Korean, then—in a moment unique in the book—in Korean: “I call him the names to let him know that I see him the way how he is.” To be named is to be seen, to be claimed. This, for Sae-ri, is the strongest possible testament of her maternal love.

In “Skinship,” the collection’s title story, So-hyun and her brother Ji-ho leave their father behind in Korea and relocate, with their mother, to Annandale, Virginia, where they move into their aunt and uncle’s house. The story is framed as a recollection told many years later, and it describes almost incidentally the outlines and strangenesses of their new American life: the scorn of Susie, So-hyun’s cousin; the sinister presence of Mouska the cat; the patriarchal lecturing of their uncle, who, unlike their handsome father, looks like “a potato on a body that is like a larger potato”; the humiliating treatment of So-hyun’s mother by her sister and brother-in-law. Eventually, complicatedly, the children’s father joins them in the States: “The way he held a spoon—with a locked wrist—was at once a thing I’d forgotten that I instantly remembered.” Choi manages to convey much that is unspoken but present for So-hyun: her conflicted loyalties, her pride, her painful, unspeakable understanding.

“Here was my secret,” So-hyun tells us. “You did not feel lonely or alone if you were observant. You could make a little nest for yourself in your observation.” Not only does it make you feel safe, “to watch what others were doing. To notice things they didn’t notice”—it makes you a writer.