Downtown Pulaski, Virginia. All photographs from Virginia and Tennessee, June 2021, by Balazs Gardi for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

Derek Craft, a six-foot-eight right-hander out of east Texas, carefully guided his 1995 Toyota pickup through the final winding miles of his journey to Pulaski, Virginia. Worn-out after a long day driving north from Florida, Craft felt a spike of adrenaline as the night enveloping Draper Mountain gave way to the bright lights of Calfee Park. Perched proudly above the darkened town of Pulaski like a citadel, the stadium has lit up summer nights there for more than eighty years, immune to the forces that have eaten away at this once prosperous textile and railroad town. It was the spring of 2019, and Craft, a sixteenth-round draft pick, had been assigned to pitch for the Appalachian League’s Pulaski Yankees.

He arrived the next morning for his first day of work dressed, as usual, in jeans, boots, and a cowboy hat. Pulling into the parking lot, he was greeted by the groundskeeper of the 3,200-capacity stadium.

“Can I help you, Cowboy?” the man asked. “The field is closed.”

Craft explained that he was on the team.

“The Yankees have a cowboy?” The groundskeeper laughed. “No way.”

Five hundred miles from Yankee Stadium, where fewer than 15 percent of Pulaski’s players would ever hit the field, Calfee Park might as well be on another planet. Gerrit Cole signed a nine-year, $324 million deal to play in the Bronx; Craft would make less than $5,000 for the season. Many of his fellow players would teach, drive for Uber, or bartend in the off-season to supplement their incomes. Meanwhile, they were acutely aware that they might have just a few hundred at bats to earn a promotion and keep their dreams alive.

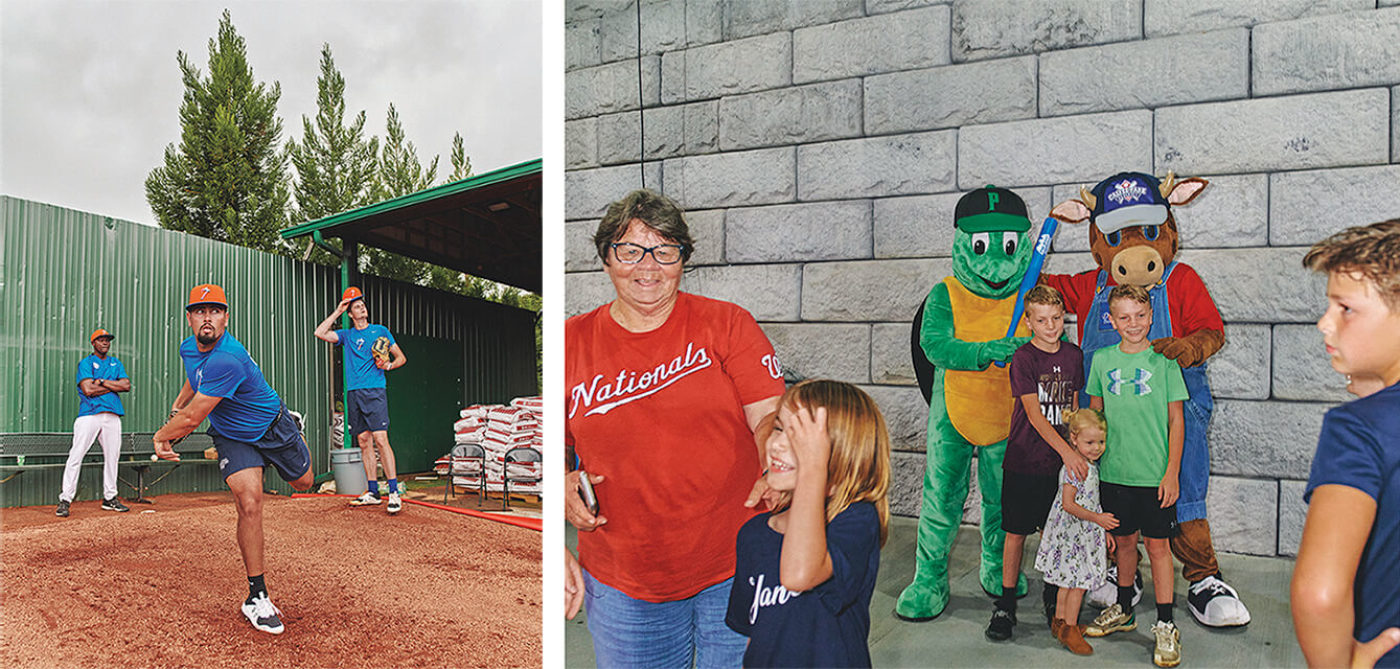

But the experience still had its magic. Little kids—and, sometimes, young women—would eagerly wait outside the clubhouse for autographs. This close connection between players and fans distinguished the Appalachian League from more advanced professional circuits. During his one season in Pulaski, Craft later told me, he would look out into the grassy pavilions during games and see kids playing Wiffle ball and football: “It took me back to my own childhood and made me feel comfortable.” Admission is six bucks and the promotions are endless: Dollar Mondays, Taco Tuesdays, Thirsty Thursdays. A family of four can purchase parking, two adult tickets, two child tickets, four hot dogs, two sodas, two beers, and a program for around the price of a single nosebleed seat in New York.

With a powerful fastball, a trademark victory salute, and his cowboy ensemble, Craft quickly became a crowd favorite. Early in one game, a teammate sitting beside Craft in the bullpen nudged him and said, “Hey, look at that guy holding his son over his head with the boots, jeans, and cowboy hat . . . He’s dressed up just like you.”

Craft signed a ball and sent it up to the kid. After the game, he went out of his way to greet the family. The boy, Carson Hamblin, was five years old, and had a twelve-year-old sister named Carlie. They were there with their mom, Courtney, and dad, Brandon, a firefighter and third-generation Pulaski fan. Craft soon found himself heading to the family’s farm on off days, driving Carson around the pasture on their four-wheeler. Brandon Hamblin challenged Craft to pitch to him on their lawn one afternoon, and after a few whiffs managed a weak grounder—something he’s still proud of.

When Craft was promoted to Staten Island later in the season, he left his old pickup in the hotel lot across the street from the firehouse; Hamblin would text him every once in a while to let him know it was still there. After the season ended, Craft returned to Pulaski to pick up his truck. He wound up staying on the farm for a few days, playing with Carson and Carlie and helping take the calves in.

Not long after his visit, word leaked that the Pulaski Yankees’ days might be numbered. Major League Baseball had developed a plan to dramatically pare the number of minor-league franchises. According to rumors, the Appalachian League would be eliminated. Reporting at the time suggested that the plan was the brainchild of Jeff Luhnow, who was then the general manager of the Houston Astros.* (Not long after, Luhnow would be suspended and then fired over a sign-stealing scandal.) Luhnow found an eager champion in the MLB commissioner, Rob Manfred. Luhnow, an alum of the Kellogg School of Management and McKinsey; Manfred, a Harvard Law School graduate; and Manfred’s deputy, Dan Halem, another Harvard Law graduate, embody the league’s new technocratic leadership, forever on the lookout for “efficiencies.”

For most of its existence, America’s network of minor-league teams has served as a development system for the majors. At any given time, a big-league franchise has forty players on its roster but more than two hundred others under contract, farmed out to minor-league clubs. These clubs are mostly privately owned but governed by ongoing agreements with the major-league teams with which they are affiliated. Players are moved from affiliate team to affiliate team—as Craft was moved mid-season from the Pulaski Yankees to the Staten Island Yankees—according to the needs of the parent franchise.

The proponents of contraction argued that the expansive minor-league system was a wasteful anachronism; hundreds of players with no hope of making the majors populate teams just for the purpose of evaluating a few top prospects. Much of this work, the thinking went, could be replaced by a system of quantitative analytics that would allegedly identify the next generation of superstars. “It was crazy to have an entire league set up so a handful of top picks can have real games to play,” a former Appalachian League player said. “It was an elaborate ruse that there is a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.”

But was it? What about those who considered their time in the Appalachian League the highlight of their professional lives, as well as a source of potential future jobs, not to mention a lifetime of stories told over beers? What is baseball? Our national pastime, an enduring slice of Americana? Or just a business? Does an enterprise that purports to be part of the fabric of America—and one that for the past hundred years has enjoyed a unique federal antitrust exemption—have a responsibility to prevent that fabric from fraying? Or should the league simply maximize value for its owners, as most corporations do?

These were the questions that brought me to Pulaski. I was convinced that this was an important story, one that I wanted to tell. I have to admit that, like any writer who comes across an idea that seems big enough for a book, I could also see the story as a remarkable professional opportunity. Eager to learn more, and to gather material for a proposal, I flew to Raleigh, North Carolina, rented a car, and began getting to know the teams in the Appalachian League, their management, and their fans.

A wealthy transplant from Massachusetts named T. J. Wallner opened Pulaski’s first textile plant in 1916. An ardent baseball fan, Wallner recruited men to field a team that would compete in an industrial league against mills and foundries from neighboring communities. Calfee Park was constructed by the Works Progress Administration in 1935. Professional baseball arrived seven years later, in the form of the Pulaski Counts. This was a golden age for baseball in the region; fifty-five semipro teams dotted Alamance County, North Carolina, alone. The Counts soon joined the Appalachian League, founded in 1911, and became an MLB affiliate. Before becoming the Yankees, Pulaski’s club had deals with the Phillies, Cubs, Braves, Rangers, Blue Jays, and Mariners.

Pulaski rivaled Roanoke in local importance until I-81 bypassed it in the late Sixties, killing off scores of mom-and-pop restaurants and motels that lined the now-obsolete Lee Highway bisecting town. Heavy industry had already left for places like Gary, Indiana. After NAFTA, Pulaski Furniture moved overseas. As local economies cratered, I-81 became the “heroin highway.” What had been a vibrant downtown was now empty after dark, a warren of boarded-up buildings.

Throughout this decline, “baseball was the constant,” John White, a former Pulaski town official, told me. “It was the glue that held the community together.” Onetime mayor Nick Glenn seemed to channel Bowling Alone author Robert D. Putnam as he described the hollowing out of the community’s traditional gathering places—churches and civic organizations such as the Lions Club, Kiwanis, and Rotary. Even the local YMCA is struggling.

Glenn’s daughter, Meredith McGrady, reckons she has been to over a thousand games at Calfee Park but has never set foot in an MLB stadium. “We don’t have anything now,” she says. “Baseball is the last thing to draw people in.”

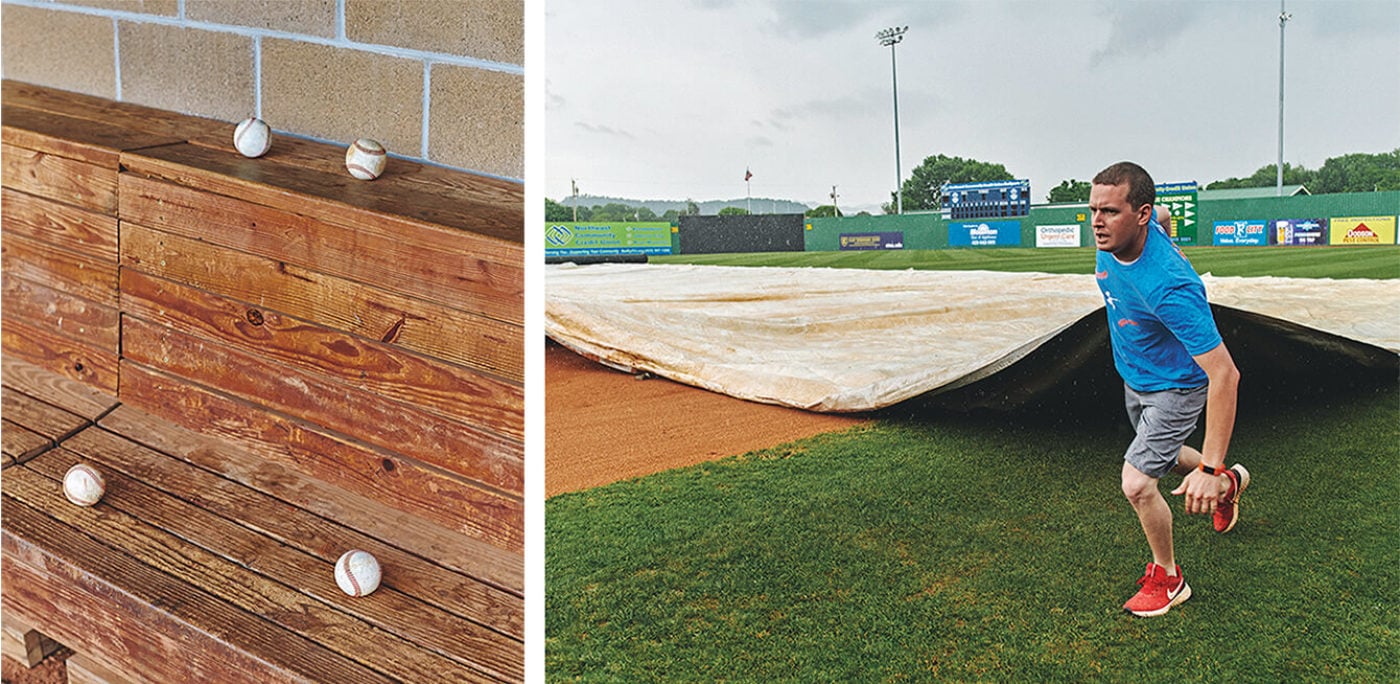

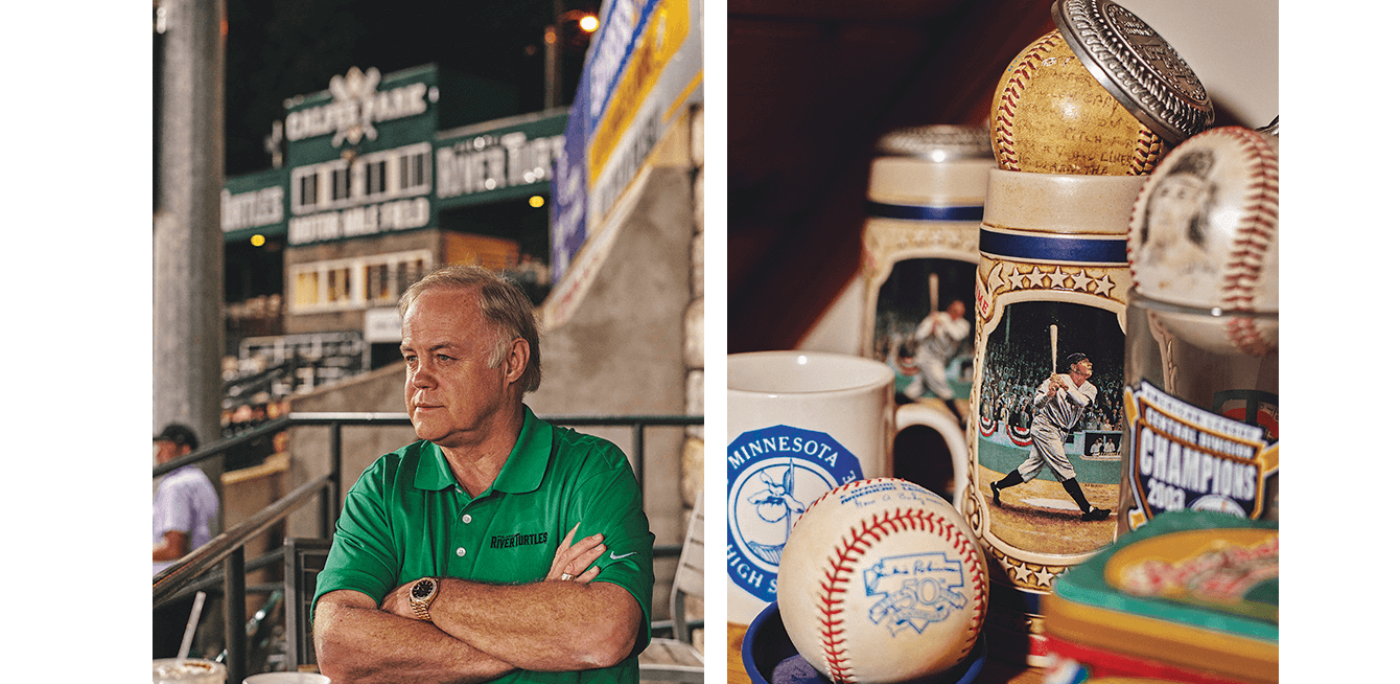

Professional baseball in Pulaski had faced a crisis once before, when the Seattle Mariners pulled up stakes in 2014, citing substandard facilities. But David Hagan, a successful car dealer from the area, bought the neglected ballpark from the financially strapped city. Hagan is a larger-than-life figure in Pulaski, and his fingerprints are on everything from a boutique hotel downtown to housing developments. He immediately pumped several million dollars into stadium upgrades and coaxed the Yankees to bring an affiliate to town. What had long been among the league’s most dilapidated facilities became its crown jewel. The year that Craft arrived to pitch, Ballpark Digest named Calfee the top rookie-league ballpark in the nation.

Having spent years reinvesting in the community, Hagan is something of a small-town Steinbrenner, holding forth on summer nights in what locals call his “cigar lounge” at Calfee Park, where he has not missed a game in five seasons. Though Hagan says he has been invited to Yankee Stadium dozens of times, he has never gone, seemingly content in his own fiefdom.

Hagan may have saved baseball in Pulaski, but his general manager, Betsy Haugh, helped it thrive. Haugh, who played soccer at Marshall University, was just twenty-five when she took the front-office job. She began aggressively marketing games, regularly putting in eighty-hour weeks during the season. Pulaski has a population of about nine thousand, over two thousand of whom regularly jammed into Calfee Park. The first fireworks night in three decades drew a record crowd of more than four thousand. On military night, young people took their enlistment oaths in center field and veterans were admitted free of charge. Haugh, who lived in a small cottage located just beyond the right-field foul pole (batting-practice home runs would occasionally land in her front yard), went long stretches without leaving this small parcel of Yankees property, a remote embassy of the House That Ruth Built.

Despite the challenge of selling tickets in a small, financially distressed market, Haugh managed to turn out the biggest crowds in the league. In 2019, just as MLB was finalizing plans to shut the Appalachian League down, the team was honored with the annual John H. Johnson President’s Award for being the nation’s most successful minor-league franchise.

During my first reporting trip, I spoke not just to Pulaski’s owner and general manager, but to fans such as Jeff Martin, a fifty-one-year-old family services counselor at Highland Memory Gardens Cemetery, who finds at Calfee Park a chance to be with people on the “best days of their lives, instead of their worst.” During one game, Martin saw a video on the Jumbotron advertising the Adopt-a-Player program, in which locals help players acclimate to Pulaski, and agreed to participate. He was assigned a young pitcher named Tyler Johnson. Martin would later learn that Johnson had overcome a congenital heart defect and undergone multiple operations before he was six months old. Now, though, he was mostly worried about his mother, who had been diagnosed with chronic leukemia. A cancer survivor himself, Martin developed a special rapport with Johnson.

“The Yankees bring the world to my heart, and my heart to the world,” Martin—who is prone to philosophical reflection—told me. He came to see Johnson as a second son, feeling protective if someone booed him. At Waffle House after the game, Martin would help Johnson forget about a poor performance with tales of his own embarrassing professional moments, such as when he mistakenly sang “Jingle Bells” to a group of increasingly bewildered graveside mourners who’d requested the Christian hymn “Ring the Bells.”

Returning home to Denver with stories like Martin’s, I felt buoyed by the sense that I had gathered powerful material for a book proposal. At the same time, I felt the stress mounting after months of reporting work without earning a dime. My family’s lease was ending, and we knew that we would have to move, but had no idea where. I sometimes woke around 4 am with a pounding headache, worried about our future, trying to shake a sense of unease that my commitment to telling this story—and pursuing my own literary ambitions—was making me an irresponsible father.

I was encouraged when my agent told me that several top publishing houses liked my proposal. When he called one morning that spring to tell me I had a deal to write a book about the Appalachian League’s farewell season, I couldn’t suppress my excitement. The only catch was that there had to be a season; if it was canceled because of the pandemic, the agreement would be void. I wasn’t too worried; the season wasn’t scheduled to begin for months, and baseball is played outdoors, where transmission is rare.

Far away from most of their minor-league affiliates both geographically and culturally, thirty millionaires and billionaires huddle behind closed doors to make decisions about the future of Major League Baseball. There are many theories as to why they chose to target one quarter of minor-league teams for extinction. The decision likely stemmed from a convergence of factors, most notably the sense that there was no need for such a vast infrastructure to assess and groom future MLB players, coupled with a desire to save money and exert more control over baseball at all levels.

Manfred, the commissioner, talked about that desire for control—what he dubbed “One Baseball”—in a 2015 speech:

Major League Baseball is committed to the idea that we are going to be more actively engaged with all parts of the baseball community. . . . We want one umbrella effort, with Major League Baseball at the top of it, but involving college, high school, and various youth programs. Going forward, we have to attack the youth and amateur market in a single, unified, and coherent way.

His choice of words is revealing. Rather than publicize the fact that eliminating baseball in forty-two cities and towns would save MLB an estimated $500,000 per team (roughly the cost of one major-league minimum salary), league officials argued that the cutbacks would in fact be beneficial to minor-league players, allowing for modest pay raises for those who survived the cuts, as well as an improved quality of life, including better travel accommodations. (Though with revenues reported at over $10.3 billion in 2019, owners could have easily paid for this without cutting jobs.)

The league also suggested that because only a fraction of drafted players ever make the majors, late-round picks would be better off never being teased by the opportunity. Citing the long odds of making the majors, an MLB executive asked, “Have we really served kids if we convince them to leave college, and they do so because they think they have a chance, and then one day they are taken aside and told, ‘You’re not good enough,’ and are then outside on their butt?”

Does a major-league club really need close to three hundred players scattered across more than a dozen leagues? Even most proponents of a robust minor-league system concede this is worth examining. But the former Minor League Baseball president Pat O’Conner bristles at the myopic focus on player development. MLB sees minor-league baseball as being little more than an “R & D lab for future big-league players,” O’Conner says. “There is the game of baseball and the business of baseball, and the business side is winning, which is not always good for the long-term health of the game. . . . For these towns who have hosted baseball for one hundred years to be summarily dismissed is not right and not in baseball’s long-term interest.”

Not everyone was overlooking the essence of baseball, though. In fact, by the beginning of 2020, minor-league advocates had begun pushing back. A bipartisan effort in Congress to stop contraction, led by legislators from a number of affected communities, most notably Bernie Sanders—whose hometown Vermont Lake Monsters were reportedly on the chopping block—was gaining steam.

As spring 2020 blossomed in Appalachia, the pandemic showed no signs of abating. Still, fastballs thumped into catcher’s mitts in Florida and Arizona, a reassuring constant as stress mounted elsewhere.

Then, on March 13, MLB suspended spring training. This left the Appalachian League’s management in a doubly tenuous predicament: the contraction plan meant that this would likely be their final season; now the pandemic meant that MLB might shutter minor-league ballparks for the summer. If this came to pass, the century-old league might have already recorded its final out.

I began obsessively checking the COVID-19 case numbers in Appalachian League communities, monitoring statements from the governors of Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia, trying to divine where they were headed when it came to restrictions on large gatherings. Our family started to house hunt in the area, hoping to find a base of operations for my research and writing. I almost felt as though I could expend enough psychic energy following COVID-related developments to somehow will the season to happen. I couldn’t help fantasizing about bringing my own family to the occasional game, and imagining my son’s glee over the crazy antics of the mascots.

With no games to watch, I began talking with the league’s general managers: Haugh, Zac Clark of the Johnson City Cardinals, and Brice Ballentine of the Elizabethton Twins. Occupying the lowest rung of professional baseball’s executive ladder, these young general managers—all still in their twenties—were cramped into austere offices, working long hours and suffering sleepless nights, preparing for a season that might not happen—all for clubs that could soon be eliminated.

Like their players, they weren’t in it for the money. The $35,000 or so they earned in a year equates to what some senior major-league executives make in days or weeks. (Manfred reportedly earns roughly $11 million a year.) But they dreamed of advancing in the fiercely competitive profession they loved, energized by the opportunity to bring families and communities together at the ballpark, and excited to carry business cards that read general manager, embossed with major-league logos.

They plowed ahead with their plans for the summer season, despite receiving little guidance on what to expect. Ballentine—who, at twenty-nine, had already worked for the Quad Cities River Bandits, Burlington Bees, Hickory Crawdads, Hagerstown Suns, Wisconsin Timber Rattlers, and Mobile BayBears—took it upon himself to figure out what safety precautions would be necessary to allow spectators to return. He purchased gloves and masks, installed plexiglass at the concession stands, and drew up seating plans for 50 percent capacity. Sitting in his sparsely furnished office adorned with old bobbleheads and promotional jerseys, under a whiteboard tracking local sponsorship deals (dr. enuf—yes, pizza inn—no), Ballentine grudgingly conceded that they probably wouldn’t be able to get a bouncy house for the kids, but were considering buying a $150 roll-away basketball hoop and charging for shots: “That could help us make a few bucks.”

As he strategized over how to pull in a few additional dollars, MLB remained focused on getting major leaguers back on the field. Players and owners haggled over how to hold a shortened season with hundreds of millions of dollars in TV revenue at stake. Meanwhile, the minor leagues’ negotiating position weakened by the day, as franchises with already thin margins suffered through months with no income.

The league’s general attitude toward the minors seemed to be encapsulated by one former MLB executive’s diagnosis: “Minor-league baseball hires a few kids to sell tickets and create promotions and keeps all the revenue . . . It’s a good model for them. If someone else is going to pay my labor costs for a new business, I would do well, too.” Never mind that MLB had successfully lobbied Congress in 2018 to pass the shamelessly named Save America’s Pastime Act, which exempts minor-league players from minimum-wage laws under the guise of saving cash-strapped franchises. Though top draft picks are able to pocket large signing bonuses, most selections in the later rounds receive only modest bonuses to accompany a standardized pay scale that comes out to less than what fast-food workers earn.

Like so many others dealing with the unpredictable consequences of COVID, my own situation was growing more precarious, as I continued to pay out of pocket for reporting trips in service of a book whose viability was becoming more tenuous. As I ate a McDonald’s combo meal in a roadside hotel outside Johnson City, Tennessee, after a long day of interviews, I had to question what the hell I was doing.

The lack of clarity was beginning to exact a psychological toll on everyone—myself included. “If there isn’t going to be baseball, just tell us, rip the Band-Aid off,” Zac Clark of the Johnson City Cardinals told me.

Haugh’s low point came when she tried to eke out a few dollars with a screening of Frozen II at Calfee Park and the audiovisual system gave out. As she scrambled to fix it, I imagine she felt as I had on a few occasions, shuttling drunk millennials around Denver for Lyft in an effort to make a few bucks between reporting trips.

With each passing week, the stress mounted. Haugh was concerned that if the Yankees abandoned Pulaski, all her unsold merchandise from the previous year would become worthless, as would the thousands of bobbleheads inbound from China. She worried over the broader consequences of contraction.

“Kids used to come with their grandparents, and now all of that could be lost,” she told me. “All they will know is baseball on TV, and that isn’t the same. These memories will disappear.”

On June 30, 2020, it was announced that affiliates would not be provided with players because of COVID concerns, thereby canceling a season for the first time since the establishment of the minor leagues in 1901. Residents of the ten Appalachian League communities were now forced to accept the likelihood that they had already witnessed the last professional ball game in their towns.

One morning, while having my first cup of coffee, the beautiful Denver weather contrasting with my anxious mood, I felt my heart quicken when I saw an email come in from my editor. My fears were confirmed: the book deal was terminated, per the terms of my contract, as there was now no season to cover, and my six months of research and writing appeared to have been a waste. We moved to Pittsburgh, a more affordable city that was closer to my wife’s family, but still within striking distance of the Appalachian League communities that I still hoped to write about.

On a warm August night, I drove down to the Fatz Cafe outside Pulaski to meet McGrady, the daughter of the former mayor. As the 2020 major-league season hobbled along with games played in empty stadiums, she expressed her frustration with MLB: “COVID was used by MLB as an excuse to devastate small-town America,” she said. “I can’t hang out with friends. Concerts were canceled, and now baseball is gone. It’s depressing.” She said that kids now just stayed up all night playing video games.

The Scotch-Irish people of Appalachia take pride in their independence and grit. Just over a century ago, Pulaski’s mayor, Ernest W. Calfee, for whom the ballpark is named, led the town courageously through the Spanish flu. In an eerie foreshadowing of our COVID response, he ordered the closure of what we now call nonessential businesses. The local Southwest Times, in the more flowery language of the era, wrote:

John Crouch, the grave digger, then a young and powerful man, labored long and hard—fortified by an occasional shot of whiskey he managed to fight off the flu and stay on his feet throughout the epidemic.

Pulaski suffered worse than any other town in the state: two fifths of its five thousand residents got sick, and one hundred and twenty-five died. As has been the case throughout the region’s history, though, they took the punch and got back up.

McGrady explained the ways in which Pulaski was struggling with the lockdown. As in much of the country, big businesses such as Lowe’s and Walmart were doing well, while mom-and-pops such as the Blue Ridge Fudge Lady shop had to transition to serving by appointment only. The economic forces buffeting these small businesses and the Pulaski Yankees were similar, as in both cases multibillion-dollar national brands would weather the storm—if not make a profit—while local vendors offering the same product would get flattened.

The season’s cancellation crushed the finances of minor-league operators, putting them on life support and further weakening any negotiating leverage they had with MLB. The pandemic also distracted the public, allowing MLB to avoid the scrutiny the move would have ordinarily generated.

Just about everyone I spoke to—fans and management alike—viewed Manfred as the paradigmatic corporate villain. “I doubt he has even been to an Appalachian League game,” one former Appalachian League GM told me. “He deals in leverage, and will wait until the last minute, when these clubs are most desperate, and throw them some nickels.”

Hagan, who owns the Pulaski team, bristled at the fact that his club could be recognized as the best franchise in minor-league baseball in 2019 and slated for elimination a year later. “We’re a little town, I got that,” he says. “But look at what we have—the best stadium, great attendance, and great facilities.” He marvels at how MLB entered negotiations with a list of demands and emerged having achieved all of them: “If two sides go into a negotiation, each with ten dollars, and one side comes out with nothing and the other with twenty dollars, that’s not a negotiation—that’s a hostile takeover.”

I drove to Elizabethton’s Northeast Community Credit Union Ballpark through an August twilight. Pulling into the lot, I saw the longtime manager Ray Smith sitting outside the ballpark with Lisa Pearce, a woman with cerebral palsy who had barely missed a game in twenty years. Pearce’s home, where she’d been living alone with her Chihuahua since her husband passed away, contained a shrine to her beloved team, a bedroom bureau stacked with Twins baseball cards, uniformed teddy bears, a scrapbook of news clippings, and several bobbleheads. Smith stopped by weekly to clean her sheets and provide the companionship she’d been missing since she lost her state-provided caretaker. Her family lived on nearby Roan Mountain, a place whose natural beauty is scarred by ramshackle trailers and the occasional meth lab. They didn’t visit often.

Smith, who at sixty-four still displayed the lean and athletic frame that earned him a ticket to the big leagues back in 1981, seemed to have stepped out of another age; he was prone to corny expressions, referring to his playing days as “back when dinosaurs were roaming the earth.” In his small office, he reached into his desk and produced a stack of handwritten scorecards from the previous summer, a charmingly antiquated archive. Smith was widely recognized as the quintessential rookie-league manager, with a remarkable record for getting players to the big show.

As we took a slow walk across the still well-maintained infield of the empty park, Smith reminisced about old games with near-photographic recall, and with an enthusiasm and sense of wonder for the sport that do not seem to have dampened over the years.

One of the plans being bandied about by MLB was for an elite league of college prospects to take the place of the Appalachian League’s professional teams. When I mentioned this to Smith, he had no interest. “I’m a big-league guy,” he said matter-of-factly. Told that MLB cited substandard facilities and long travel times as two of the reasons for cutting minor-league teams, Smith had emailed Manfred and invited him to Johnson City, offering to bring him on a tour. The league’s ten towns were located within short drives of one another, and—with a few notable exceptions, like the chicken-coop lockers and hilly outfield in Bristol—the facilities were more than adequate. Smith applauded Manfred for responding to the message, though the commissioner declined the invitation.

Before I pulled out of the ballpark lot on this August evening perfect for baseball, I slowly scanned the empty grandstands one last time. Missing were the smiling kids tugging at their parents’ arms for cotton candy, and the “back-row gang” of mostly older ladies, some of whom haven’t skipped a game in years.

I tuned my radio to the comforting cadences of the Yankees–Red Sox game as I drove into the Appalachian sunset and toward my hotel. Between innings, news broke that Yoenis Céspedes had just quit playing for the New York Mets, ostensibly because of concerns over COVID, though later reporting suggested it was just as likely because of frustration with his contract. Watching this superstar walk away from his team (and fans) in the final months of a four-year, $110 million contract, following months of bickering between MLB players and owners, convinced me that these were not people I wanted to support. Yet a few minutes later, I turned the radio up to better hear the game over the sound of my Jeep. The sport still exerted a hold on me that I couldn’t shake.

On September 28, 2020, MLB released a promotional video announcing the new Appalachian League, trumpeting plans for an elite college summer league to replace the professional teams. Beginning play in the summer of 2021, the new amateur league would include some of the top rising freshman and sophomore college players in the country. The players would not be under contract and the clubs would not be affiliates, but MLB agreed to provide financial support for the new league. (The exact terms were undisclosed.)

The video was expertly produced, featuring the former major leaguer Harold Reynolds saying that the quality of baseball would be even better than before, going so far as to claim that a staggering half of the league’s three hundred amateur players would end up in the major leagues (a contention that prompted eye rolls from most baseball insiders I spoke to).

The video had the feel of a Madison Avenue creation, crisp and catchy, a notable departure from the homespun old Appalachian League. Mark Cryan, a former general manager of the league’s Burlington Indians and now assistant professor of sport management at Elon University, described the old league as “a throwback league, a time machine,” whereas this one was clearly envisioned as a step into a more technologically sophisticated future. The MLB press release announced that “analytics and data will also be a driving force behind the new vision for the Appalachian League.” There was something jarring about seeing the world of spin rates, launch angles, and exit velocities encroaching on one of the last preserves of a simpler game, one closer to its essence.

An MLB executive I spoke to touted the new league’s marketing potential, observing how, in the past, outfield fences in the Appalachian League would advertise Joe’s Towing and bail bonds, while now they could sell national rights and oversee them from headquarters. The potential loss of the long-standing connections between these teams and local businesses went unremarked. Joe from Joe’s Towing is more likely to come to the games, spend time with his neighbors, and do things like sponsor local Little League teams than are distant executives at Google.

Since their inception shortly after the Civil War, minor-league clubs have been run by pirates, hustlers, and wheeler-dealers, P. T. Barnums for whom no promotion was too zany if it got people to the ballpark. Cryan fears that MLB is slowly eating away at this treasured piece of Americana, warning that even the clubs that survive contraction will continue to be gobbled up by MLB as part of its “One Baseball” quest as their valuations drop. It doesn’t take an MBA to imagine a scenario in which MLB could simply say, “We’ll offer you $3 million for an $8 million team, and if you don’t sell, we’ll just cut you out of the next agreement.”

Apart from the skill disparity between college players and drafted professionals (which can be debated), just as important to these communities is the pride that accompanies association with a major-league team. There was something magical in seeing the Yankee pinstripes in Pulaski, Virginia, something that transcended the talent on the field and provided a connection to the world beyond Appalachia.

I meet McGrady for a beer one last time at Fatz on a pleasant October evening. She was saddened by the fact that she had attended her final Appalachian League game and hadn’t even known it at the time. She felt bad for her friend Betsy Haugh, who had recently hosted a Duck Derby fund-raiser for the local YMCA, featuring races between floating yellow rubber ducks for the kids. When the skies opened and unleashed a downpour, everyone bought old Yankees gear to stay warm.

I tell her about a recent visit to Haugh’s small office overlooking Calfee Park, where Haugh told me that the team’s new name would likely be the River Turtles, in honor of the nearby New River. I recall how she said she hoped it would appeal to kids, attempting enthusiasm that came off a little flat. McGrady knows what we all know: the Turtles can’t compete with the aura of the pinstripes, no matter how well marketed the new brand might be.

McGrady tells me that people are stuck at home and desperate to get out and do something. It is no wonder local suicide numbers are up, she says, when people have no social interaction. I recall with a jolt our last dinner, when she volunteered that her husband, Wally, had taken his life in the summer of 2017. The rate of deaths by suicide, drug overdose, and liver failure is 37 percent higher in Appalachia than in the rest of the United States. She and Wally had been high school sweethearts, sharing a love of the Yankees. According to his obituary in the local paper, Wally “was best known as the voice of Calfee Park, spreading smiles throughout the stands nightly.”

McGrady says that the only games she missed that summer were the day after Wally’s suicide and the day of his memorial service. She was overwhelmed by the outpouring of support she discovered when she returned to the ballpark and her box was overflowing with flowers and wreaths. Wally’s initials were on all of the Yankees’ batting helmets, and a memorial video for him played on the Jumbotron. “David Hagan even gave me a hug that night,” she says, laughing because it was “the only time I will probably ever hug that man.”

On my final visit to Elizabethton, I drive to the ballpark, where I see Smith sitting glumly on the bed of his pickup truck, with Pearce seated next to him in her wheelchair. They are joined by Smith’s assistant coach of nineteen years, Jeff Reed. Still muscular and somewhat imposing despite the twenty years since his final major-league game, Reed teases me for being late, shouting, “Ten minutes late, run ten poles!” They are quick to tell me they have no interest in playing roles in the new college league.

Smith, aware that this might be my last visit, and recalling my mention of an undistinguished junior-varsity college baseball career, invites me to take some batting practice in a nearby cage. Deflated when I arrived, he gets energized as he loosens up his arm and I grab a nearby bat. As he begins serving up easy fastballs right down the middle of the plate, I am relieved to make solid contact, twenty years after I last set foot in a batter’s box. Smith’s mood improves by the minute.

From outside the cage, Reed tells the story of Nate Hanson, an obscure minor leaguer, who apparently ripped a line drive through the protective net in this very cage and took out one of Smith’s front teeth. Reed says he scooped the tooth off the ground and returned it to Smith, who tried to jam it back in before continuing with batting practice. “Nate the Great,” Smith shouts as he continues pitching to me, “probably the hardest contact he ever made!”

Once the stories begin, they flow easily and without interruption. After twenty-seven seasons serving as manager in Elizabethton and forty-three years with the Twins organization, Smith will soon be left with only memories, as the era of professional baseball in Elizabethton comes to an end.

Fans rise for the national anthem ahead of a game between the Pulaski River Turtles and the Burlington Sock Puppets at Calfee Park, June 13, 2021

On June 5, 2021, baseball returned to Calfee Park. It was a lovely night, and a healthy crowd had turned out to watch the Pulaski River Turtles take on the WhistlePigs from nearby Princeton, West Virginia. The teams were part of the new Appalachian League. Smiles abounded as ballpark friendships rekindled.

Pulaski would ultimately fall to Princeton, 6–3. Most fans stayed in their seats after the final out, though, because Hagan had planned a lavish postgame fireworks show. As “Take Me Home, Country Roads” blared from the sound system, one could almost feel the previous year’s anxieties dissipate into the fireworks smoke. Carson Hamblin, still wearing the cowboy hat inspired by Derek Craft, was all smiles as he rode toward the exit on his father’s shoulders, blissfully unaware that Pulaski’s minor-league team had been replaced by rather ordinary college players.

As I joined the crowd streaming out the original Gothic stone gate, I felt a part of a procession dating back to the park’s 1935 opening. Still, it wasn’t quite the same. A young boy seated in the row behind me had mumbled to his father, “The Yankees were a lot better.” Harold Reynolds’s projection that 150 of the league’s 300 players would make the majors was looking to be off by about 145.

The cynic in me agreed with Pat O’Conner, the former minor-league president, who suspects that the new league is a short-term effort to appease Congress, and likely to be quietly shuttered in a few seasons after top college prospects prove reluctant to play in places like Princeton, West Virginia. But at least on this night, 648 days after the last professionally played Appalachian League out was recorded there, life had once again come to Calfee Park. The romantic in me hopes MLB’s distant decision-makers will see the magic that can’t be captured on a balance sheet, so that the kids tucked in their car seats, clutching stuffed River Turtles, can someday take their own kids to the park, maybe even to see professional ballplayers on a diamond nestled in the rolling hills of southwest Virginia.