Collages by Jen Renninger. Source photographs: top © Getty Images; and bottom © Michele and Tom Grimm/Alamy

On a warm day in August 2020, after five months of lockdown, I donned a mask and ventured onto the streets of my hometown of Richmond, California, across the bay from San Francisco. It was my first day as a census enumerator, a job I had taken out of both curiosity and financial necessity. My assignment was to visit, at a safe distance, neighbors who had been isolated for months, weathering interminable Zoom meetings or shepherding their kids through the quagmire of online school. Arriving uninvited and ringing the doorbell of a stranger at this moment in history felt vaguely suicidal—or worse, homicidal. But it was my job to take such risks, for the sake, as I understood it, of the public good.

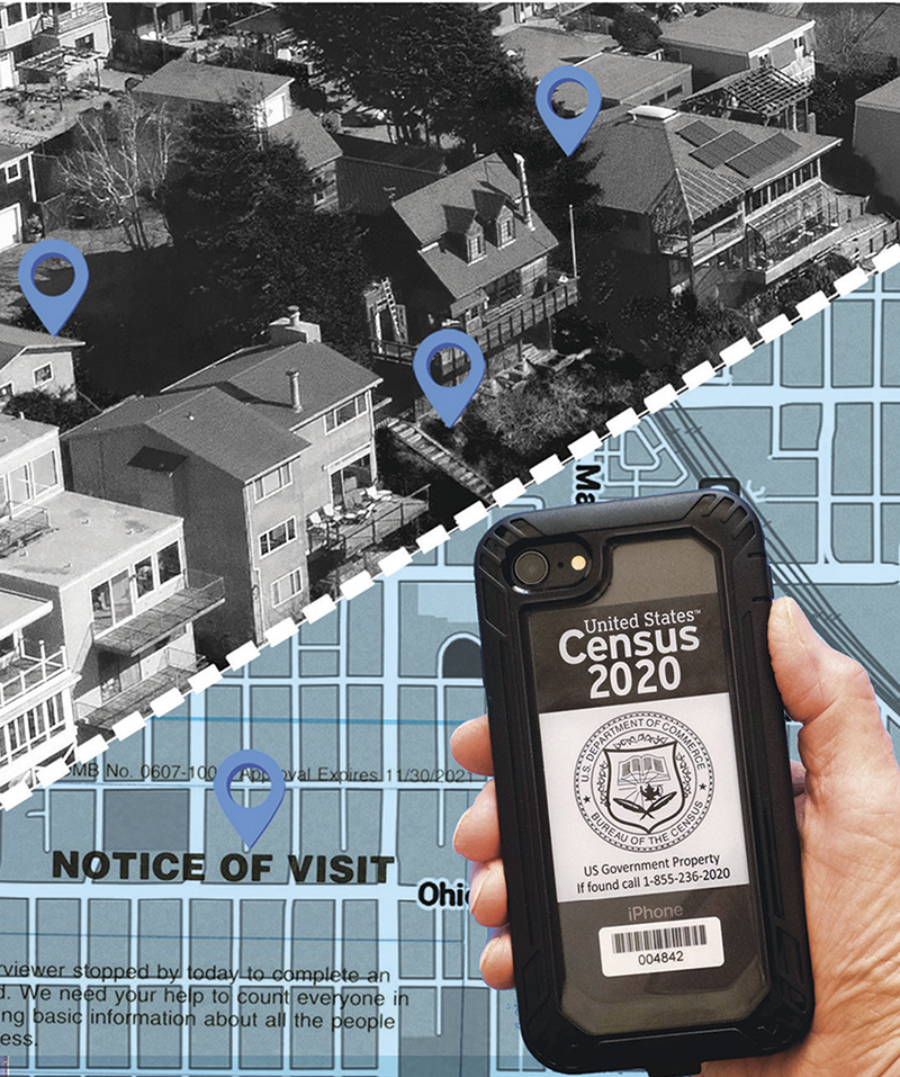

I was equipped with the following: a loaner iPhone stamped with an official Commerce Department seal; a bag depicting the U.S. Census logo containing two surgical masks, a bottle of hand sanitizer, and a raft of official forms; and a photo ID with a seven-digit code denoting, presumably, my low station in the fiefdom of Donald Trump’s Department of Commerce. I clicked a blue icon on the phone’s home screen and opened an app called FDC, short for Field Data Capture. Amid a tangle of digital roads were roughly forty house-shaped icons indicating addresses where residents had yet to complete their surveys. I was tasked with visiting all of them, in predetermined order, over the course of a single day.

One icon led me to a small bungalow on Arlington Avenue, concealed in a thicket of tall trees and bushes. This was my first assignment, or NRFU, as it is known in census-speak. A beloved abbreviation among those at the bureau, NRFU stands for “non-response follow-up,” though it is often used by supervisors to refer to enumerators themselves, e.g., “The NRFU is the human face of the Census Bureau.” Census higher-ups, perhaps in an attempt to keep things conversational, pronounced the term as an acronym: nerfoo.

From the sparse notes on the FDC app, I determined that I needed to find my way to rear unit b, though there was no sign of a second domicile. Baffled, I consulted my phone. I clicked through a series of menus, confirming that I was attempting the address and specifying that no one answers. The next prompt asked whether the unit appeared to be occupied or unoccupied. Just as I was ready to select the latter, I heard a voice coming from inside a small shed on the opposite side of the driveway. An orange extension cord snaked across the concrete and under the door. Illegal conversions had become increasingly widespread in the Bay Area, and it was not unheard of for people to pay hundreds of dollars per month to live in sheds like this one. Could this be rear unit b?

I rapped lightly on the door, and the voice inside went silent. “Hello,” I said. There was no response. I clicked my phone once more, and it spat out a twelve-digit alphanumeric code, which I quickly scrawled onto the Notice of Visit (NOV), a small piece of paper left behind when respondents are not home or wish to complete their surveys online or over the telephone. I double-checked the number, hastily tucked the form into the pickets of the gate, and retreated.

Back on the street, I looked again at my phone. The map led me to a quiet cul-de-sac and—after I’d papered several more entryways with NOVs—to the patio of a beige ranch house. There I met a woman in her sixties named Suellen. Her mother, who had owned the home, hadn’t filled out her census form, as she had died the previous year. Suellen was in the process of going through family mementos for the upcoming estate sale. She told me that her mother had worked as an enumerator during the 1970 census. While cleaning out the house, Suellen had found her badge. “She loved working for the census,” she said.

Suellen recalled that many of her mother’s friends from the neighborhood had also worked for the census to make extra money. Back then, she said, there was a stronger sense of community around the count. Everyone answered their doors. I told her that sounded lovely, like a different world. Then I proceeded into the FDC script: “So the house was unoccupied on April first?”

My efforts that day were mostly unsuccessful. I completed only a handful of interviews. Nearly all of my knocks and rings were met with curt refusals or nothing at all. Yet I still somehow found myself behind schedule. It seemed impossible to keep up with the assigned pace. With half an hour remaining in my five-hour shift, I’d only managed to reach roughly thirty of the forty houses. Were enumerators expected to run to each case?

I assumed that my failure to complete all of my assignments would be met with a reduction of work or, at the very least, a call from a supervisor. I was wrong. When I checked my phone the next morning, the home screen announced that I’d received another full caseload.

I had never considered becoming an enumerator until the pandemic, when my family, like millions of others, was driven into financial hardship. My wife lost her job as an executive for a Korean cosmetics company, and our subsistence on my unpredictable wages as a freelance writer and adjunct professor grew increasingly untenable. Then, an invitation arrived in my inbox: be a census taker. The message was superimposed over the image of a handsome man whose immaculately whitened smile suggested he’d just received the promotion of a lifetime.

At $25 an hour, the work was a potential lifeline. As a journalist, I was intrigued by the possibility of observing the enterprise—“the federal government’s largest and most complex peacetime operation,” according to the National Research Council—up close. How, I wondered, could the government safely send hundreds of thousands of people to knock on doors across the country in the midst of a pandemic? A single enumerator could visit dozens of homes on any given day—a seemingly perfect scheme for spreading a highly infectious respiratory disease.

Compounding my fear of the virus was the Trump Administration’s effort to wield the census as a political weapon, particularly in communities it viewed as hostile to his reelection. In 2019, Trump floated the idea of adding a citizenship question to the survey; then, last July, he signed a memo to exclude undocumented immigrants from the count altogether. Foiled in federal court, the administration tried a new approach. Then–secretary of commerce Wilbur Ross announced that the census would end a month earlier than scheduled—even though it had started almost three months late—a move that critics said would disproportionately harm minority communities that are already systematically undercounted. (A federal court would later reverse this decision.)

In hindsight, we know that the 2020 census was more or less a disaster, rife with counting errors and political manipulation. (It was also particularly consequential for California, which would lose a congressional seat for the first time in the state’s history.) But at the time, I believed that the Census Bureau’s mission—to “count everyone living in the country once, only once, and in the right place”—was a mostly noble one. And yet there was a great tension between this vital civic duty and the exigencies of mass illness. In light of the mounting death toll, it was hard not to see the count as a potentially devastating undertaking.

Despite the risks, I applied for the job, and after several months I was hired. In early August, I was invited to attend an accelerated two-hour training seminar at a new charter high school along the Richmond waterfront. I was directed toward the assembly hall where the materials for our enumerating work sat atop school desks spaced six feet apart. Trainees—who looked to be anywhere from their late twenties to early seventies—filed in. One older man was dressed in pressed slacks and a blue button-down shirt. The younger man beside him wore a T-shirt that read sorry i’m late. i didn’t want to come. For some of us, it seemed, plodding into the community in the middle of a pandemic was an economic necessity; for others, it was merely a way to make a few extra bucks.

The proceedings were led by a man in his mid-sixties named Walter. After some introductory remarks riffing on what he viewed as the Trump Administration’s meddling in the count, Walter turned to the new rules put in place to guard against COVID-19 transmission. These changes were unprecedented in the census’s 230-year history, he said, but necessary to carry out an accurate count during a pandemic that, at the time, had resulted in more than 4 million infections and 150,000 deaths in the United States. Some of the guidelines—wearing a mask, sanitizing one’s hands, and keeping six feet of distance from interviewees—were obvious. To appease the most germophobic of respondents, Walter said, we could conduct interviews on the phone while standing on the property. “If you go this route, try to maintain visual contact with them as you go through the survey,” he said. “Do not let respondents, under any circumstances, particularly if they are elderly, make contact with your device.”

Each trainee was given a small cardboard box containing an iPhone in a plastic case. After a quick overview of the phone’s basic functions and the bureau’s software, we were instructed to turn them on. A few of the older trainees asked where the power switch was. We were told that this was a historic moment—the first time that a decennial census NRFU count would be carried out entirely by smartphone. This spurred chatter about issues of security and privacy. A man sitting beside me was startled when his phone rang as soon as he’d turned it on. “Who’s calling me?” he asked, puzzled.

“It’s probably a solicitor,” said one staffer, nonchalantly. “We’re going to get a lot of spam calls.”

Once our screens were aglow, we were instructed to click a blue icon, logging us on to the census server, known as The Hub. The tech staff informed us that we would be connected to this digital umbilicus for the duration of our employment. A woman seated in front of me speculated that we’d also be on the government’s radar. “They’ll be tracking us, y’all,” she said, pivoting in her chair and casting a stern gaze around the room. “Better be on your best behavior.”

After class, we were required to complete an additional twelve hours of training at home. This consisted of online quizzes and short video clips featuring a cheerful woman with long brown hair, dressed in an expensive-looking suit, working her way through a variety of situations an enumerator might encounter. In one, she demonstrated how to conduct an interview with non-English speakers; in another, she de-escalated a situation with a hostile respondent who insisted that the government was up to no good. None of these videos addressed the pandemic, rendering some of her tactics—stepping into the path of a door so it could not be shut, for instance—laughably irrelevant.

And that was it. Armed with our devices and less than two days of training, we nerfoos had become fully deputized agents of the federal government, deemed ready to hit the streets.

Source photographs: aerial view of Richmond, California © Jane Tyska/Digital First Media/East Bay Times/Getty Images; a row of new houses in Richmond © Gino Rigucci/Alamy; houses in Richmond © Camilo José Vergara

As it happened, my first day offered a fairly accurate template of what was to come. I had expected my government-monogrammed shoulder bag to command more respect, so I was surprised at how difficult it was to get people to complete a survey—even after they’d answered the front door. Only when I realized just how little weight the imprimatur of the Census Bureau carried did I begin to have some success. The job called for a door-to-door salesman’s approach, requiring the nerfoo to adopt patronizing or outright obsequious poses. A compliment aimed at the landscaping or the neatly polished car often went a long way, as did an apologetic tone:

“Sorry to bother you.”

“I know you’re busy.”

“Can I steal ten minutes of your time?”

When this technique failed, which it often did, I was forced to be more creative. At one house on Cypress Avenue surrounded by a tall fence, I slipped through a locked gate alongside a UPS deliveryman. Through a large picture window, I saw a woman with a toddler on her lap. Taped to the door trim was a driver’s license, presumably placed there to facilitate the flow of goods schlepped to their doorstep by a constant stream of delivery drivers. I waved, but the woman ignored me. The child, however, gestured back, forcing her to acknowledge my presence.

“What do you want?” she asked loudly, her voice muted through the double-paned glass.

I swung my shoulder bag toward her, revealing the Census Bureau logo. “Do you have ten minutes to complete your census survey?”

“Not today!”

I told her I could call her if she was concerned for her safety.

She shook her head.

I asked if I could leave a notice on her door explaining how to complete the survey online.

“No!” she said emphatically. “Now please go!”

As I wandered around Richmond for the first time in months, I found myself dazed by the extent of the economic transition it was experiencing. Postwar bungalows with peeling paint and weed-strewn front yards stood beside homes of the same vintage that were undergoing slapdash rehabs. The flips were easily identifiable by their xeriscaped lawns, festooned with succulents, and their stylish paint jobs (usually in muted shades of beige or gray) offset by the boldly colored front doors that nearly always presaged a for sale sign.

The homes not yet overcome by this wave of speculation were outfitted with metal security doors—vestiges, I heard from neighbors, of a time when break-ins were more common. The most imposing ones were essentially slabs of steel riddled with small holes, like giant cheese graters. These entryways presented particular challenges to us nerfoos. The metal absorbed the blows of knocking hands, and their tight frames offered nowhere to tuck NOVs. On the off chance that someone answered, the security doors tended to remain closed, rendering the person on the other side an unsettling silhouette.

All of this is to say that I found the stoutness of the front door to be inversely correlated to the probability of completing an interview. On Sonoma Street, for instance, I arrived at a house whose front entrance was fitted with a wooden security door. I knocked and heard a mechanical click.

“U.S. Census,” I said sheepishly.

“Nope,” said a male voice from the other side. Then came another sharp click, which, in my heightened state, I hesitate to admit, I thought sounded something like the cocking of a gun. I backed away quickly and didn’t bother to fill out an NOV.

But my door-profiling method was not always reliable. On Kern Street, I stepped onto a landing covered in pots of blooming flowers. I knocked on the security door, and a large, stern man with tattoos covering half his face emerged. I looked over my shoulder and took measure of the stairs to see if I could clear them in a single leap, in case a quick escape was necessary. Instead, the man shooed me away politely, almost professorially, as he peered through the iron bars.

“No thank you,” he said demurely before closing the door.

By contrast, at a bungalow on Humboldt Street without a security door, a gentle-looking man in a sweater told me that the federal government had no business asking for his personal information, particularly during a pandemic. I apologized, then tried to sway him with the census’s patented A+ Method, assuring him that his information would be kept confidential. In response, he told me to leave. If I returned, he said, he’d happily “punch me in the face.” I entered the interaction into my case notes.

The following day, I was surprised to find the same address on my case list. I called my supervisor, Nas, who sounded as if he’d just awoken from a nap. I explained the hostile encounter and suggested that we avoid sending another enumerator to the house. Nas (short for Andronicus) exhaled heavily. He’d heard about this problem from other enumerators already. His solution was simple, though not one I had learned in training. “It seems like it’s a problem with the FDC program,” he said. “If an address seems dangerous, just skip it.”

From its inception, the U.S. Census has involved mustering a large temporary army of counters to canvass neighborhoods and collect information. The first census, in 1790, turned loose sixteen marshals, one territorial governor, and hundreds of subordinate deputies across the country. (Each enumerator was paid a dollar for every fifty to three hundred people counted.) From the beginning, there have been questions about its methodology and accuracy. Many Americans were concerned that the census could lead to new taxes and refused to be counted. Others recalled in fear the Old Testament tale of King David, who almost brought a plague upon Israel for the sin of having “numbered” his subjects. George Washington himself expressed doubt about the accuracy of the final tally of 3.9 million, a figure he felt certain was far too low.

The goal of counting every American “once, only once” might seem, on its face, a neutral governmental function akin to filling potholes or fixing sewer lines. But because census figures are used to determine congressional representation and redraw districts, the count and its statistical methods have long been mired in politics. For decades, the systematic undercounting of minorities has benefited those looking to disenfranchise non-white communities. In other words, the Trumpian effort to manipulate the 2020 count is not a new phenomenon. It can be traced to the nation’s founding and the three-fifths compromise, which solidified the political power of Southern states by tallying each slave as a fraction of a person despite their lack of representation. The census’s democratic ideal of counting everyone has always been tempered by the deeply ingrained antidemocratic belief that some of us should count for less.

The days progressed, and the fog disappeared, replaced by smoke surging in from the many wildfires burning across the state. As the air quality declined, the location of my assignments shifted from the wealthier Richmond neighborhoods in the Berkeley Hills toward the poorer neighborhoods in the industrial flatlands. In the hills, where I spent most of my first week, over 80 percent of residents had already completed their forms. But in these “hard-to-count” tracts—some of the poorest neighborhoods in the Bay Area—the response rate rarely exceeded 65 percent.

To complicate matters, coronavirus case rates were rising dramatically in these same areas. Given Trump’s race-baiting and my poor Spanish, I presumed that many of my black and Latino neighbors would be hostile to my presence. I can’t say I blamed them.

What I found, however, was that residents of Richmond’s more diverse enclaves were generally more willing to answer their doors and respond to my questions than those in the whiter, more affluent neighborhoods in the hills. At one house on Humboldt Street, a woman with glittery eye shadow translated for her Spanish-speaking mother, who answered my questions while stroking an ancient terrier. On Tulare Avenue, I spoke with a young man who seemed so exhausted that he struggled to keep his eyes open. I asked whether he’d like me to come back at another time. “No, that’s okay,” he said, insisting on forging ahead. “This is important, right?” An energetic young woman of Salvadoran descent living in a large apartment complex in Richmond broke protocol and sidled up to me as I typed in her responses. Noticing a data-entry error, she grabbed the phone from my hands. I told her, with an incredulous laugh, that we were not allowed to let respondents touch our phones.

“Sorry!” she replied as she continued to type in her corrections.

I wondered whether this eagerness sometimes masked a certain anxiety. Several Latino residents I interviewed asked whether they needed to show identification or a passport to verify their answers. (They didn’t.) Others I interviewed were quick to divulge that they, or more often their children, were “born here,” though I hadn’t asked. I replied that the census did not take one’s immigration status into account, but most of them did not seem to believe me.

After two weeks of such interactions, my enthusiasm began to wane. As the election inched closer, more and more news reports surfaced about Trump’s efforts to disenfranchise minority communities. It became hard not to feel that we nerfoos had been transformed into unwitting G-men—agents of racial antagonism in khakis and comfortable shoes. A journalistic uncertainty also gnawed at me. As I furtively scrawled notes between assignments, I wondered whether I might be in violation of some unwritten ethical code. Since I did not disclose to respondents that I was a journalist, I agonized over whether these interactions were fair game. (As David Foster Wallace once wrote in this magazine of the pitfalls of participatory journalism: “It all gets quite tricky.”) After much hand-wringing, I concluded that key aspects of the census could be understood only from the vantage of the enumerator.

There was, for example, the matter of management. The cost of the census, according to recent estimates from the Government Accountability Office, was roughly $14.2 billion in 2020. The most expensive single aspect of the count was the complicated hierarchy of supervisors and enumerators needed to coordinate the NRFU operations. And yet, despite the enormous cost, we received virtually no guidance from actual human beings. Instead, we received messages from The Hub.

Correspondence would pop up on our phones at seemingly random times. Most of these short messages offered general reminders—Enumerators must wear masks; Don’t forget to submit hours each day—but others read like targeted threats. One, for instance, warned us never to tell respondents that their participation would preclude any future visits from census workers. (The bureau, we were reminded, carries out dozens of counts annually.) Another thanked us, in a somewhat accusatory tone, for not sharing residents’ personal information. Because we were using a device capable of tracking our locations and monitoring our activity, I couldn’t rule out the possibility that the disembodied warnings and admonitions were directed at me personally. I was reminded of the words of my fellow nerfoo trainee: Better be on your best behavior.

I tracked the progress of our NRFU efforts on the census’s Hard-to-Count website in real time. The response percentages in the three tracts I worked slowly ticked up each day, a quarter point here, a tenth of a point there. But the longer the work went on, the less the needle moved. According to a Census Bureau report, in-person visits were expected to result in completed interviews only 12 to 15 percent of the time. I was lucky to secure an interview half as often. Consequently, the same homes kept cropping up. These were the hard cases: the chronic nonresponders, the extreme procrastinators, the occasional government-haters. Their case notes described paranoia and, sometimes, outright aggression. One respondent said he was never mailed a census form and had therefore written off the idea of being counted altogether: “They fucked up. Fuck ’em.”

Some of these addresses were labeled “dangerous.” These were rendered on the map as red triangles with exclamation points. Each day, more appeared, scattered like land mines across the city. But it was impossible to know whether the address had been flagged because of something as serious as a life-threatening interaction, say, or just a yapping dog. Other repeat visits were to homes that may not have been occupied at all. Piles of children’s shoes scattered about the front porch or a cat perched in a window were unmistakable indicators that a residence was inhabited. But what to make of the apartment on San Pablo Avenue with dozens of dead plants arrayed neatly around a tiny landing? Or what of the house on Wilson Avenue whose entryway was covered in languid strands of faux Halloween cobwebs so thick they had to be pushed aside to reach the door, even though it was not yet September?

I also found myself frequently visiting respondents who insisted that they had already completed their surveys. During a visit on Cherrywood Court, a man politely explained that he had met with several census workers in previous weeks. I fumbled for an explanation, speculating that there was a lag in the Census Bureau software. But, of course, I had no idea. I merely went where my phone told me to go. He seemed to understand my predicament: “If you can, please let them know, okay?”

When one of these repeat addresses came up on our case lists, we were often prompted by the FDC software to seek out a “proxy”—census-speak for a neighbor who knows the respondent well enough to share some of their personal information. Persuading people to divulge details about their neighbors required a subtle diplomacy. Many respondents—particularly older residents—scoffed at the idea of revealing their neighbors’ birth dates, homeownership statuses, or ethnicities. On one cul-de-sac, an older woman with long nails and perfectly coiffed gray hair laughed when I asked whether she had a moment to share some basic information about her neighbors, whom the census had been unsuccessful in reaching. She shook her head and responded in rapid Spanish that I could not follow.

“No entiendo,” I said, to which she replied, “Like I would tell you.”

Other proxies apologized for not knowing more about their neighbors. “Sorry, they keep to themselves,” said a man on Cypress Avenue. “I’d tell you if I knew anything. I think one of them is named Jessica. Or maybe it’s Jamie, but I’m not sure. That makes me sound like a shitty neighbor, doesn’t it?”

At the end of my grueling second week, I was directed to a large, fortresslike apartment complex. In the leasing office, one of the building managers glanced at my census lanyard and rolled her eyes. “Is this going to be over soon?”

I apologized and told her that the count was supposed to continue until the end of October. “Just so you know, lots of people aren’t answering their doors because of coronavirus,” she said. Over the previous month, she explained, she had received five or six daily visits from census workers. “I’m constantly handing over the keys. I’m hand-sanitizing twenty times a day. Do you see the problem?”

I agreed that the system was not ideal, but then found myself reiterating the official line: The census is mandated by Congress. The census is vital for the funding of schools, roads, health care, not to mention the fair apportionment of congressional seats. Census workers, by law, cannot be barred from entrance.

As I spoke, the building manager produced several rings of keys and laid them on her desk. “I guess I’m just going to have to live with it.”

Taking the jangling mass in hand, I proposed that the leasing office provide the Census Bureau with information as a proxy for its hard-to-reach tenants. The building manager replied that she could tell us how many people lived in each unit, but could not release any private information. Maybe she could encourage tenants to complete their surveys instead? “We’re having a hard time these days just getting people to pay their rent,” she replied scornfully. “I don’t think we’re going to have much luck convincing them to turn in their census forms.”

I nodded and excused myself. After roughly an hour of wandering through the labyrinthine complex without completing a single interview, I walked back to the office in defeat. The building manager seemed to sense my poor outing and gave me a wry smile.

“Hand sanitizer?” she asked.

A month before my assignment was set to end, I awoke to find an unfamiliar message on my phone: You do not have any new Census work for 9/2/2020.

Until that morning, my iPhone had been a seemingly endless wellspring of assignments. What had I done to upset it? Though I was eager to end my tour as a foot soldier in the nation’s largest peacetime operation, the sudden curtailment of work was concerning. Had my NRFU batting average dipped below the bureau’s Mendoza Line and tripped an algorithm that barred me from future assignments? Had my phone—in addition to keeping tabs on my location—been secretly listening in on my conversations with respondents? Had my inscrutable supervisors found my interviewing style suboptimal? As census workers, we were told repeatedly that we must protect the personal information and privacy of the public at all costs. But what had we sacrificed in terms of our own?

I decided to give it a day. If no new assignments appeared on my phone the following morning, I’d call Nas to ask what was going on. Then, that afternoon, while wandering the aisles of a local pet store with my son, Owen, I received a call from Allentown, Pennsylvania.

“Hi, Jeremy,” said the tired voice on the line. It was Nas. “I’ve got some bad news. We’re going to need you to turn in your stuff.” I asked if I had done something wrong. “No, nothing you did,” he replied. “We’re shutting down operations in the area.” This, of course, contradicted the bureau’s previous assurances that we’d have as much work as we wanted through the end of the month. It was also not entirely clear what the “area” was. A few census tracts? The city of Richmond? All of California?

Nas offered no details, just another sigh. “It sucks, but there’s just no more work for us,” he said. He asked me to meet him at a nearby Starbucks in an hour, and to bring my iPhone along with the rest of my materials.

“Did you just get fired, Dad?” Owen asked after I hung up.

“No, there just isn’t any more work,” I replied.

“So that’s pretty much getting fired, right?”

I headed home, collected my gear, and drove to Starbucks. When I got out of the car, I was greeted with a honk from a gold sedan. Behind the wheel was Nas. A set of dog tags dangled from the rearview mirror. He raised a hand, beckoning me over. When I got within a few feet of the car, he raised his palm, gesturing for me to stop, and rolled down the window. I passed over my phone and shoulder bag, and he sifted through the contents with a ballpoint pen.

“Where’s the box?” he asked.

I shrugged.

I vaguely remembered being told in training that we were supposed to return all of our items in their original packaging. Thankfully, I hadn’t thrown the box away. “I’ll be back here tomorrow at noon to get the stuff from some other people,” Nas said. “Just come back then.”

On my way home, I noticed a man in front of a row of apartment buildings. He was wearing a shoulder bag and was hunched over an iPhone—the unmistakable tableau of the 2020 census taker. He was tall, wore a beige baseball cap, and was probably in his mid-sixties. I pulled over and introduced myself, not as a fellow employee (as I no longer was one), but as a local journalist.

His name was Roy. He had also heard that the count was winding down in the area. “I don’t know for sure why we’re stopping now,” he said. “I doubt if I have much more than a few days of work left here anyways. I’m pretty much only knocking on neighbors’ doors. It’s very slow.”

Assuming the worst, he had already orchestrated a backup plan. “I responded to some emails a couple weeks ago about traveling out of the area,” he said, explaining that he had been invited to work in a whiter, wealthier part of the county. I wished him luck and let him get back to work.

When I returned to my car, there was a final message from Nas on my census phone, offering a meager severance: Hey, put an hour and mileage in on a timesheet and submit it tonight. And with that, my small part in the 2020 census came to an end. In a little under a month, I had netted exactly $1,078.40.

Shortly after my dismissal, I was surprised to receive an email asking whether I was interested in working for the census again, this time as a supervisor. Out of curiosity, I completed the form, which turned out to take even less time than the enumerator application had. After I completed the short quiz, the website returned a message: “Experienced—your application may be considered for future employment.”

I haven’t heard back.