All artwork by Steve Mumford for Harper’s Magazine

Source photographs courtesy the author

My flight from Munich to Warsaw on March 13 was half-filled with English-speaking men in a motley assortment of store-bought paramilitary gear, cargo pants, and hiking boots. A faint odor of dirty laundry and stale cigarette smoke emanated from their general direction. One wore a cap that read in my defense i was left unsupervised. They appeared to be anywhere from twenty to fifty years old, and looked like they might have been dredged up from the aisles of sporting goods stores across the United States. Some snored; others watched videos. It was the last leg of a long journey.

After disembarking, I followed the train of men to the baggage claim. I introduced myself to one of them, a man in his late twenties with a reddish beard. His name was Ray Lehman; he was from Pennsylvania, and had served in the Marine Corps. “You look like a Marine,” I told him.

“I get that a lot,” he said.

“Where are you headed?”

Lehman looked away. “OPSEC, man,” he said. “OPSEC.” He walked over to a currency exchange window and produced four or five ziplock bags full of money from a variety of countries. “Do you take won?” he asked. Loose coins spilled out and rolled across the floor. “I have three thousand one hundred and seventy-five yen.”

Other Americans began to emerge into the dingy, ill-lit arrivals area: Jack Potter, a heavily tattooed thirty-two-year-old from Washington State, who owns a company called Guerrilla Tactical, and Kieran Atherton, a Texan whose fledgling business, The War Club LLC, sells night-vision goggles on Instagram. They were trying to rent a car, and suspected that they had been scammed by a company that turned out to have no location at Warsaw Chopin Airport.

Matthew VanDyke, a gaunt, bearded forty-two-year-old from Baltimore, grabbed his rucksack from the carousel and strode purposefully toward the exit. He was trailed by Lehman; a muscular man with a deep scar under one eye; an ABC News cameraman; and a Vietnam veteran wearing a crumpled pinstripe suit, his white hair in a ponytail. This was William Devlin, the co-pastor of Infinity Bible Church in the South Bronx, and a professor at Nile Theological College in Khartoum, Sudan. “I’m just here to pray and assess and share God’s love,” he told me.

These men were only a few of the great many Americans who sought to make their way into Ukraine via Poland in the weeks following Russia’s invasion. They were joined by disorganized groups of fighters from England, Scotland, Ireland, Canada, Sweden, Norway, France, Spain, the Czech Republic, and elsewhere in Europe, with lone wolves trickling in from places like South Korea and Peru. Many were combat veterans or had military training. Some had fought the Islamic State in Syria with a Kurdish militia known as the YPG. A few had already seen action in Ukraine’s Donbas region, where war with Russia-backed separatists has smoldered since 2014.

They made the journey at the explicit invitation of the president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky. Just days after Russian tanks rolled across the border from Belarus and Crimea, Zelensky declared the formation of a new military unit that would consist entirely of foreign volunteers: the International Legion for the Territorial Defense of Ukraine. “Every friend of Ukraine . . . please come over,” Zelensky said. “We will give you weapons.”

The Ukrainians created a recruiting website and put out a slick video describing 4 simple steps to join heroic army. Veterans with combat experience were strongly preferred, but anyone was welcome. A week after Zelensky’s announcement, Ukraine’s foreign minister, Dmytro Kuleba, told reporters that they had recruited twenty thousand troops from fifty-two countries—a figure roughly equivalent to one tenth of Ukraine’s active-duty army.

I had previously reported on the foreign volunteers fighting the Islamic State in Syria, a mix of black-bloc leftists and apolitical war enthusiasts from Europe and the United States who, at their peak in 2017, numbered less than two hundred. Few as they were, they had struggled to cohere as a group. A handful of bad apples had caused problems for the Kurds. An inability to speak Kurmanji or Arabic had limited their efficacy in battle. At least thirty were killed.

The wave of volunteers headed to Ukraine was supposed to be orders of magnitude larger. To muster a cohesive battalion out of such a polyglot rabble, and do so before what most analysts predicted would be a swift Russian victory, seemed all but impossible. Yet the Ukrainians purported to have already deployed foreign fighters. On March 7, the defense ministry released a photo of ten men from the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Lithuania, Mexico, and India, grinning in a sandbagged trench, armed and uniformed like soldiers of the Territorial Defense Forces, Ukraine’s rapidly expanding reserve militia. A statement from the defense ministry declared that the first volunteers were “already in position on the outskirts of Kyiv.”

I couldn’t tell if this was a pure propaganda stunt or if war in Europe might really bring about a twenty-first-century reprise of the International Brigades of the Spanish Civil War. To see for myself, I took the first of the “4 Simple Steps” and sent an email to my nearest Ukrainian consulate, in Houston, attaching a scan of my passport and U.S. Army service record. I received no response.

Judging from conversations on Reddit, where a message board for would-be volunteers had swelled to thirty-five thousand members, I wasn’t the only one whom the Ukrainians ignored. The prevailing opinion was that they were overwhelmed with emails, and determined volunteers should simply fly to Poland and make their way to the border. Though the Ukrainians had one of the largest armies in Europe and a hundred thousand new enlistees already in reserve, their presumed need for warm bodies went unquestioned. One American shared a screenshot of a reply he had received from Ukrainian officials who had urged him to be patient; if he tried to contact them again, the office of the defense attaché had warned, his application would be denied. “Go to the Ukraine Polish border and tell the border guards you are there to fight for Ukraine and they will direct you,” someone advised him. “Bring as much gear as possible.” I was skeptical, but could think of no better plan myself.

The creation of the International Legion set off a massive wave of positive press. Within a few days, hundreds of articles appeared in English-language publications, some offering how-to guides for those interested in enlisting. Practically every major U.S. periodical, including the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, published glowing profiles of the Americans who were “playing a growing role as the fighting spreads.”

Moscow took notice. As I made my way to Warsaw in the early-morning hours of March 13, a volley of Russian cruise missiles struck a training base in Yavoriv, a dozen miles from the Polish border, where foreign fighters had been congregating. None of the recruits, no matter how intense their experience had been in Iraq or Afghanistan, would have ever seen such an onslaught of precision-guided munitions. Footage of the aftermath showed buildings burning around a crater that looked to be forty feet deep. The Ukrainians confirmed that thirty-five people had been killed, but denied that any had been foreigners. Meanwhile, the Russian defense ministry claimed to have killed up to one hundred and eighty. “The destruction of foreign mercenaries who arrived on the territory of Ukraine will continue,” the statement promised.

The strike left the rapidly coalescing community of foreign fighters doubtful and demoralized, but in large part undeterred. On Reddit, they continued to swap tips and bicker about whether combat experience was really necessary. Some of them seemed woefully underprepared. One hopeful, who said that he could do push-ups and “used to go every month or two to a shooting club,” wanted to know whether the Ukrainian military would provide housing with private bathrooms, and whether he could bring his pet turtle. “You’ll sleep in a hole in the ground. You’ll probably die in a hole,” another user replied. “You can bring your pet turtle. . . . He’ll probably die with you.”

The Ukrainian flag was on display all across Warsaw. Blue-and-yellow bunting decorated lampposts and storefronts, and the villainous visage of Vladimir Putin appeared on wanted posters throughout the city. Hotels in the eastern part of the country were full of people coming and going from the war—mostly going. In 2015, some 1.3 million refugees fleeing Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere had sought asylum in Europe. In the previous three weeks alone, about 1.8 million Ukrainians had fled to Poland.

I reached the Medyka border crossing on March 17. Clusters of women and children, bundled in puffy coats and lugging suitcases and backpacks, passed through the pedestrian gate in an unending stream. A tent village of aid workers had sprung up on the Polish side with an abundance of bottled water, hot coffee, canned goods, toiletries, baby formula, and pet food. Police, soldiers, and firefighters shepherded refugees onto buses. Campfires burned in the median; an assortment of flags fluttered in the wind; hippie NGO types distributed hot soup; and a thin young man in a scarf and hoodie, who had somehow dragged onto the premises an impossibly battered grand piano with a peace sign painted on the lid, played an adagio rendition of “Lean on Me.”

The would-be fighters were easy to spot. They spoke English and hung out in small groups, never far from piles of tactical backpacks. The International Legion had set up a recruiting tent on the Ukrainian side of the crossing, I was told, but most of the volunteers I found on the Polish side had already tried and failed to join.

Some, like a forty-seven-year-old former helicopter mechanic from Manchester, England, who told me he wanted to “stop that dickhead Putin,” had been rejected for lack of combat experience, which the defense ministry had made a requirement in mid-March. Others had given up on joining after the strike in Yavoriv. “The night I got here, I ran into some American guys,” said a fifty-seven-year-old retired Marine Corps gunnery sergeant from Chicago named Timothy O’Brien. “They told us they were at the base that got hit, and these guys were like, ‘Dude, do not go fucking join the legion.’ We’ve heard nothing but horror stories.” Rumor had it that the Ukrainians were using volunteers as cannon fodder. “They’re forcing guys at fucking gunpoint,” O’Brien said. “Putting you on a bus to the front with one AK and a magazine with ten rounds. I came here to fight. I didn’t come here to die.” Michael, a twenty-four-year-old Amazon driver from Massachusetts and a former U.S. Army infantryman, related the same hearsay. “The Ukrainians aren’t even fighting,” he complained. “They’re sending foreigners to the front as meat shields.”

I wasn’t sure what to make of these accounts, or of the tales I heard about the Ukrainians confiscating passports, requiring recruits to sign onerous contracts, and stealing gear. All the volunteers I met in Poland were under the impression that the legionnaires were getting slaughtered in ill-planned suicide missions. And yet the war had been going on for over three weeks, at an intensity comparable to World War II, and not one Westerner had been confirmed among those killed in action. Several weeks after the strike, the U.S. State Department told me they were unaware of any Americans who had died at Yavoriv. It wasn’t until April 29 that the Ukrainian defense ministry disclosed the first Western casualties: Scott Sibley, thirty-six, a British veteran of Afghanistan; an unnamed Dane, twenty-five, who reportedly served in the Jutland Dragoon Regiment in Holstebro; and Willy Cancel Jr., twenty-two, a former prison guard from Kentucky who had been discharged from the Marine Corps for bad conduct.

In the early days of the war, however, it seemed doubtful that any Westerners were in combat at all. The Ukrainians, as far as I could tell, were doing all the hard work of killing and dying. The foreign volunteers seemed to be little more than a media sideshow.

My first stop after crossing the border was Lviv, an ancient city of gargoyles and Gothic spires in the far west of Ukraine. It had been known before the war for its coffee roasters and breweries, and had since become a way station and clearinghouse for volunteers of all stripes. When I arrived on March 22, many of the city’s statues and monuments had been sandbagged and wrapped in plastic, and the stained-glass windows of its cathedrals had been boarded up. A Soviet-era trolley slid past a medieval battlement where soldiers stood vaping. At night, the wet cobblestones gleamed in the neon light of bars, which were limited to selling near beer on account of a wartime ban on alcohol.

Small groups of young and middle-aged men speaking French or English lingered in front of hotels, dressed in varying degrees of tactical attire and studying maps on their phones. They were easy prey for the hordes of reporters in town, who were busy filing dispatches with headlines like “Band of Others,” “Legion of the Damned,” and “Cappuccinos and Kalashnikovs”; or testimonials such as “I thought I was going to die,” “I just want to kill Russians,” and “I don’t want to be cannon fodder.”

The volunteers I spoke to mostly struck me as clueless or delusional, with no real connection to the armed forces. The Ukrainians were running a streamlined media operation, and press officers had little to offer other than what they released in daily briefs to reporters. No one could visit the front lines. Commanders did not give interviews. Field hospitals were off-limits. Soldiers repeatedly seized my phone and deleted photos and videos. No wonder regional American papers, such as the Delaware County Daily Times, were left to rely on the first-person accounts of hometown heroes such as Patrick Creed, a fifty-four-year-old Havertown man who told the paper that he was “constantly clearing houses and buildings of suspected Russians” in Kyiv. To its credit, the New York Times was careful to note that it hadn’t been able to “identify any veterans actively fighting in Ukraine.” But other outlets weren’t so cautious. The Washington Post, for instance, was eager to report that a Norwegian woman named Sandra Andersen Eira had “been on the front lines for the majority of the conflict.”

Other accounts, published in The New York Review of Books and New York magazine, portrayed some of the volunteers as antigovernment extremists, bloodthirsty psychopaths, or hopeless malcontents, but these accounts relied entirely on the dubious claims and social-media antics of would-be fighters in the United States, Poland, or Lviv, hundreds of miles from the front lines. If there was anything that could properly be called a foreign legion, I realized, I wasn’t going to find it here. I needed to go to Kyiv.

At the time, the capital was largely surrounded by Russian tanks and artillery, and the suburbs were getting shelled daily. Yet somehow the trains were still running. On March 27, I made my way to the Lviv station, which was filled with tense and exhausted men and women burdened with suitcases, children, and pets. Overhead was a high, ornate ceiling with peeling plaster arches and a Cyrillic timetable that I couldn’t read. I used a translating app on my phone to buy a ticket, and got directions from a handful of men from Canada, Sweden, and Ireland. Two of them had come to fight, including a savage-looking Swede with a Mickey Mouse tattoo on his temple. The other three were drone salesmen.

They directed me to the cavernous eastbound platform, where soldiers were checking documents. The air-raid sirens went off just as the overnight train to Kyiv arrived, but we boarded as scheduled anyway. There were few of us headed east. Half the berths in my car were unoccupied. Soon, I was fast asleep.

The minute I stepped out of the terminal the next morning, the boom of artillery was audible to the north. The city center, stately and ornate, studded with gilded citadels and domed cathedrals, remained unscathed, but the streets were nearly deserted, save for the masked soldiers manning checkpoints and machine-gun nests. The Russian offensive had faltered, but everyone seemed to agree that it was a ruse, and that the siege would be renewed. Martial law was in effect.

At a bar that was selling pints of ale despite the temporary ban, I met with a senior Ukrainian defense official who asked to remain anonymous. He was wearing a Stechkin automatic pistol under his zip-up jacket, and showed me photos on his phone of alleged Russian atrocities: a dead baby crushed under rubble; a confused civilian wandering through the wreckage; and the bodies of charred Ukrainian soldiers, the victims of what he claimed was a white phosphorus attack.

I asked him about the International Legion, and he said the government had not been prepared to receive so many volunteers. About a third of them had been turned back for lack of combat experience. “It would not be a good thing,” he said, “for them to be killed and us to have this reputation.” Another third left “after they saw real war,” by which he meant the strike on Yavoriv. The remainder had not been organized into a freestanding unit, he admitted. The volunteers were being housed at various locations around Lviv and Kyiv, and few had weapons, body armor, or helmets. There were a few highly experienced veterans at the front, he said, but that was it.

His account tracked with what I had heard from Matthew VanDyke, the freelance military trainer I’d seen at the airport. “The international legion doesn’t exist,” he texted me. “It was all propaganda to elicit international support, media coverage, and reinforce the idea that it’s the world vs Russia.” In Kyiv, he had met with a group of about sixteen legionnaires at a hotel on Peremohy Square. “Saddest group you’ll ever see,” he told me, “a clown car of misfits.” “The entire thing was an ill-conceived ploy to internationalize the conflict in the press,” he added. “They want people to apply through the Embassy because they aren’t really going to bring them here. The ones that came on their own, they’re not sure how to handle. It’s a mess.”

At Saint Volodymyr’s Cathedral, reputed to be the tomb of Saint Barbara, the patron saint of miners, armorers, and artillerymen, I met with Mamuka Mamulashvili, the commander of the Georgian National Legion, a militia of foreign fighters—mostly from the Caucasus—that has been in Ukraine since 2014. Mamulashvili, a burly, hirsute Orthodox Christian who has fought against Russia in four different wars (in Georgia, Chechnya, South Ossetia, and Ukraine), sometimes came here to pray.

I had heard that the Georgian unit tolerated foreign fighters of all stripes—including white supremacists from the United States—but Mamulashvili was quick to deny it. “We do not accept those radical organizations,” he said. “We tried to never accept them, neo-Nazis, or racists, or whatever. It’s totally unacceptable. We just kick them out.” Mamulashvili told me that of his seven hundred fighters, about one hundred and fifty were from somewhere other than Eastern Europe, and put the number of Americans at fifty. His men operate in small teams, he said, attacking Russian supply lines. During reconnaissance, they move on foot and avoid using radios or cell phones. They might spend a week in the forest, observing roads and tracking Russian vehicles before launching an ambush. They had just killed sixty Russians, he said, and captured three tanks in the village of Rudnytske. He showed me footage of the operation on his phone, and complained that Ukrainian security officials were always censoring his TikTok videos.

Zelensky’s announcement about the International Legion “fucked everything up,” Mamulashvili said. “It became a shit show because they were not prepared for so many volunteers.” Failing to locate any appreciable foreign brigade, droves of surplus English-speakers had tried to find a place in the Georgian unit. “We have no time to start training or to make new squads,” Mamulashvili said. After a few weeks, he suspended recruitment of Westerners. “I am taking only Georgians now,” he said. “To Georgians I can explain that you have to wait two weeks for a weapon to be issued. I can’t tell that to Americans. They are too impatient.”

Another unit known to accept foreign fighters is the far-right Azov Battalion, an elite militia whose neo-pagan, quasi-fascist aesthetic and Aryan supremacist ideology have long made it an embarrassment to Western liberals backing Ukraine. I found Azov’s base at an old Soviet compound on the industrial outskirts of Kyiv, where I met its founder, Andriy Biletsky.

Biletsky, dressed in an olive-green sweater, with a pistol on his hip, received me in the concrete hall of a defunct factory building, where Azov’s yellow flag, with its swastika-like Wolfsangel symbol, hung from the rafters. He denied that there had ever been Americans in his ranks. There had been U.S. trainers once, but that was it. “There are Croats,” he told me, “Belarussians, Georgians, some British if I remember well, but not many.”

As for the International Legion, “it does exist,” Biletsky said, “but it is more psyops,” intended to shore up global support for Ukraine. “It’s not practically relevant,” he said, noting that the reserve militia already had a surfeit of manpower.

While most of the Azov regiment was in Mariupol, surrounded by Russian forces and running low on water, Biletsky had come to Kyiv in search of new recruits. There were scores of frustrated foreign volunteers, I told him, looking to join any unit that would have them. Was Azov open to Americans, Canadians, Britons, and the like? Biletsky advised Westerners to volunteer in a humanitarian capacity, but he did not answer the question.

On my way out, I spotted four men in grungy paramilitary attire loitering by a wooden guardhouse. Spray-painted on it in block letters were the English words white power, along with a smiley face. I took a photo by pretending to take a phone call, but didn’t attempt to talk to the group. They were speaking English, but it was hard to hear them over the rumble of an idling armored vehicle. The only words I heard distinctly were “foreign legion.”

During my reporting in Syria, I had been able to tour the training base for foreign fighters, interview their commanders, and visit groups of them at the front, where they played a small but appreciable role in the liberation of Raqqa. Here in Ukraine, I had come to understand, I would find nothing so concrete. The main significance of the International Legion for the Territorial Defense of Ukraine, it seemed, was the win it represented for Ukraine in the information war. It had been so successful, in fact, that Russia had found it necessary to found its own international unit. Two weeks after invading Ukraine, Putin approved a proposal to deploy sixteen thousand foreign troops from the Middle East to fight alongside separatists in the Donbas, an unlikely plan that Moscow backed up by flying in a few hundred mercenaries from Syria.

The savvier Ukrainians put on a far more convincing show. The first volunteers to arrive had been interviewed, screened, offered proper contracts, and given housing. Some had been allowed to wear the Ukrainian flag and the patch of the Territorial Defense Forces. Perhaps a dozen or so had made their way to the front lines, attached themselves to Ukrainian units, and taken part in patrols. But the Ukrainians, busy with more urgent matters and deterred by the strike on Yavoriv, had done little to honor Zelensky’s promise to arm, train, and equip all the friends of Ukraine who had showed up at his invitation.

Zelensky’s move had been a brilliant exercise in wartime propaganda. The errant Westerners I had met knocking around Warsaw, the border, Lviv, and Kyiv in search of the International Legion were merely the unfortunate fallout. It was hard not to feel a little sorry for them. Few of them had college degrees or steady jobs. They had drained their bank accounts to buy winter gear, ballistic vests, medical kits, and plane tickets. A few may have been motivated by bloodthirst or white supremacy, but most I met expressed views that were centrist, liberal, or garden-variety conservative. By and large, they had simply been sucked into the spectacle. Those who were veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, a cohort now entering or well into middle age, might have felt the possibility of renewed relevance and the old thrill of being at the center of world events. Many of them are still in Ukraine, looking for something—anything—to do.

The way stations and safehouses where a few dozen of them were staying weren’t easy to find, but I managed to track one down in a converted art gallery near Saint Sophia Cathedral. It was a semiofficial base of the reserve militia, though it felt more like a clubhouse. Viacheslav Drofa, a twenty-three-year-old Ukrainian who showed me in, introduced himself as a special forces soldier but later clarified that he was a rapper waiting on his army paperwork to go through. He was dressed in a uniform of his own devising, with a knife and combat gloves attached to the front of his ballistic vest.

Inside, art featuring aliens and mathematical equations still hung on the gallery walls. Bedding, clothes, and bags were on the floor, cold pizza lay on a table, and pots and pans were stacked by the kitchen sink. Seven or eight men whose military statuses were unclear to me came and went in a patchwork of army attire, street clothes, pajamas, and shower shoes. Among them were an American named Will and a Pole named Robert.

The first question they asked me was whether I drank. A bottle of whiskey stood on a sticky table, surrounded by plastic shot glasses. I politely declined (it was two in the afternoon). Their next question was whether I smoked weed.

Down we went to a bomb shelter that they had dubbed the “smoking room.” There was a water bong made from a wine bottle immersed in a ceramic jar, and a baggie of a strain called AK-47. A bare lightbulb was set in a brick wall covered in graffiti: 4:20, mushrooms, Egyptian hieroglyphics, a star of David, a skull and crossbones. The air vents had been painted to look like vein-blown eyeballs.

A few Ukrainian soldiers, wet from the rain, came in to get high. My translator, a law student named Ihor, declined to take a rip, but I gave in. Unused to being stoned in a war zone, I stared at all the loaded guns in the room and noted with rising discomfort the carelessness with which they were handled. One soldier had a Futurama sticker on the magazine of his AK and carried a dagger with a pommel shaped like a boar’s head. A political banner depicting a blond woman with braids hung on the wall. Ihor had his arm over a box containing a DJI Air 2 drone, which we would later hand off to soldiers in Kherson. His hair was buzzed and he wore a navy trench coat with oxblood Doc Martens.

I turned to Will, the American. He wouldn’t say where in the United States he was from, or give his surname. He couldn’t have weighed more than a hundred pounds. He was in his mid-twenties and had an air of optimism about him, dressed in a beanie, base-layer shirt, and cargo pants. He had a speech impediment, and one of his eyes was slightly crossed. Though he had never been in the army, he said, “I have more experience with guns than most of the military guys coming here.”

In search of the International Legion, Will had tried to join the Georgians, who sent him to the Red Cross, who in turn gave him the address of a hospital in Kyiv that was said to be taking volunteers. He was turned away there too. “It took me a while to get the right connections,” he said. He had finally made his way to the base, where he helped the reserve unit deliver food, bottled water, and other supplies to the besieged outskirts of Kyiv. It wasn’t the front lines, but it was still dangerous work. Only a few days earlier, Robert, the Polish volunteer, had been thrown into a brick wall by the detonation of an artillery round. A doctor had spent an hour removing shrapnel from his leg, he said. His wrist and ankle were still bandaged.

Roils of smoke enveloped the crowded basement. Guys were coughing and choking, passing around a pistol for inspection. Someone turned on techno music. A lanky, haggard Ukrainian with a big beard, named Jura, sank down in a busted chair wedged between a refrigerator and the wall, a cigarette in his fingers and a Kalashnikov between his knees. He was thirty-three, and before joining the Territorial Defense Forces he had been a developer of nonfungible tokens. Jura said that the Ukrainians were using cryptocurrency at every level of the war effort, from receiving donations to buying boots, vests, and gloves. But what they needed most, he said, was antidrone technology, “good info about Russian numbers and telecoms systems,” and radio-frequency receivers, because the Russians were using unsecured channels on the front lines.

Drofa interrupted us. It was time, he said, to make a supply run, to a state-funded home for the elderly and disabled in the Obolon district. The donated foodstuffs had already been loaded into the trunks of two cars. I rode with Drofa in his tricked-out Audi Quattro, which he would total in a head-on collision with a Renault four days later. He cranked the engine, an earring in the shape of a hacksaw dangling from his ear and a chocolate-covered cookie in his mouth.

In the passenger seat was forty-six-year-old Pavel Panych. “He is a criminal,” Drofa explained. Panych had been released from prison a few years earlier, and remained an influential figure in some sort of carceral mafia. His societal contribution in these extraordinary times was to serve as a liaison between the Red Cross and what I gathered were neighborhood councils or building cooperatives in Obolon. He was bald and slim, pale and leathery, and wore a fanny pack. His glasses had tinted lenses that made them look like goggles. He smiled and made a peace sign. “This is the life,” he said.

We sped through red lights in the rain-darkened streets of deserted Kyiv, where virtually every store was closed. Some of the street signs had been spray-painted black to disorient the invaders. Russian spies had marked lampposts, the corners of buildings, and other monuments with ultraviolet paint that could only be seen with black light—the Ukrainians had already nabbed a number of saboteurs.

The banks of the Dnipro were bare mud, and at sundown the water looked as though it were saturated with blue and purple dye. A billboard depicted politicians clutching bags of money and holding their stomachs. At every major intersection there were fighting positions surrounded by antitank obstacles known as Czech hedgehogs. We had to show our documents five or six times before we reached our destination.

The home had fortunately escaped shelling. A woman named Irena Zuy came down to meet us, wearing a puffy coat. Originally from Donetsk, she had been living here, awaiting medical imaging of tumors on her back, when the Russians invaded. “This is like a nightmare,” she said.

A sound like thunder boomed in the distance: three muffled, rolling explosions. “Pretty close,” Drofa said. “But this is our troops. When it sounds like a storm, it means this is artillery from our side pushing them out.” Panych held hands with the old folks, gave them hugs, and posed for photos. He made Zuy’s daughter laugh, a little. Before we left, he distributed copies of his self-published prison memoir, Abandon Hope All Ye Who Enter Here.

By this time, it was apparent that the Russian offensive to take Kyiv had failed. The Russians’ logistical problems, ill preparation, and poor tactics, as well as the stalwart Ukrainian defense, had yielded an unexpected result. On March 29, the Russians announced a withdrawal from the northern part of the capital, though the rumble and thud of artillery on the city’s periphery continued as Ukrainian units recaptured suburbs one by one.

On April 1, they retook Zabuchchya, a small settlement on the Bucha River. The next day, I visited the area with two other reporters, two aid workers, and a young fixer. With us were two new enlistees in the reserves: Ihor, the law student who was translating for me, and Yurii, a lawyer and coffee shop owner. They had one rifle between them and no uniforms, just blue armbands on their overcoats. Our three cars were loaded with sacks of potatoes, jars of pickled preserves, loaves of bread, and bags of sugar to pass out to the people of Zabuchchya, who had been under Russian occupation for the past three weeks.

The weather was cold and wet. Wrecked cars and chunks of asphalt littered the highway, and tracked vehicles had flattened the guardrails. A gas station had been the scene of a tank battle. We passed neighborhoods that looked as if they had been hit by asteroids. Cables hung from damaged pylons. The cellular network was dead.

Leaving the main road, we stopped at a cemetery and found an abandoned SUV, stripped of its wheels, with tree branches tied to its roof for camouflage. The driver’s side was riddled with bullet holes. Dirt-battered intestines lay on the ground a short distance away, along with a large fragment of skull. Yurii turned it over with his foot, revealing buzzed, blond hair. A dog wandered up to us with its head stuck in a plastic container, but slunk off into the forest before we could help.

In Zabuchchya, people came out of their homes to meet us, looking rattled and unwashed. They showed us the damage done to their homes by artillery and rockets. The invaders had camped out in the nearby forest, they said. They had burned down the houses of policemen and threatened to shoot people. Old women wept, and old men praised the armed forces of Ukraine.

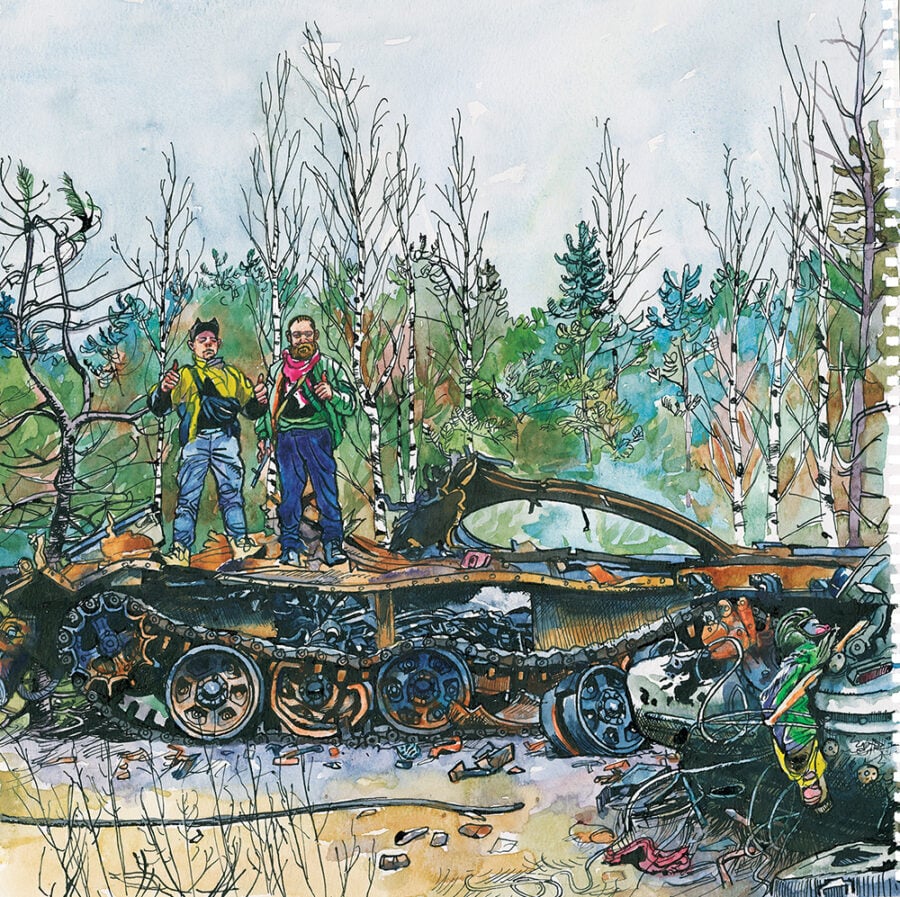

On the two-lane road leading south out of the suburb, over a quarter-mile stretch, more than a dozen tanks lay scorched, flattened, mangled, gutted by fire, and oxidized, some of them still smoking. Most had their turrets blown off, which suggested the work of Ukrainians armed with shoulder-fired antitank missiles. Misty pine forest on both sides of the road made the spot ideal for an ambush. It smelled like the remains of a campfire.

We wandered around the mechanical carnage, wary of mines. Our fixer picked up a tank periscope that must have weighed thirty pounds, and we took turns looking through the viewfinder. I spotted a blackened grenade on the ground. That’s when I noticed the man hanging in the burnt turret next to me.

He wore a padded tanker’s helmet emblazoned with the number 517. One of his arms hung out of the tank, tangled up in wires, and the sleeve of his striped jacket was shredded. A heavy metal bar, some sort of gaffe, had fallen across the hatch of the tank and prevented his comrades from pulling his body out. The top half of his face had been burned black.

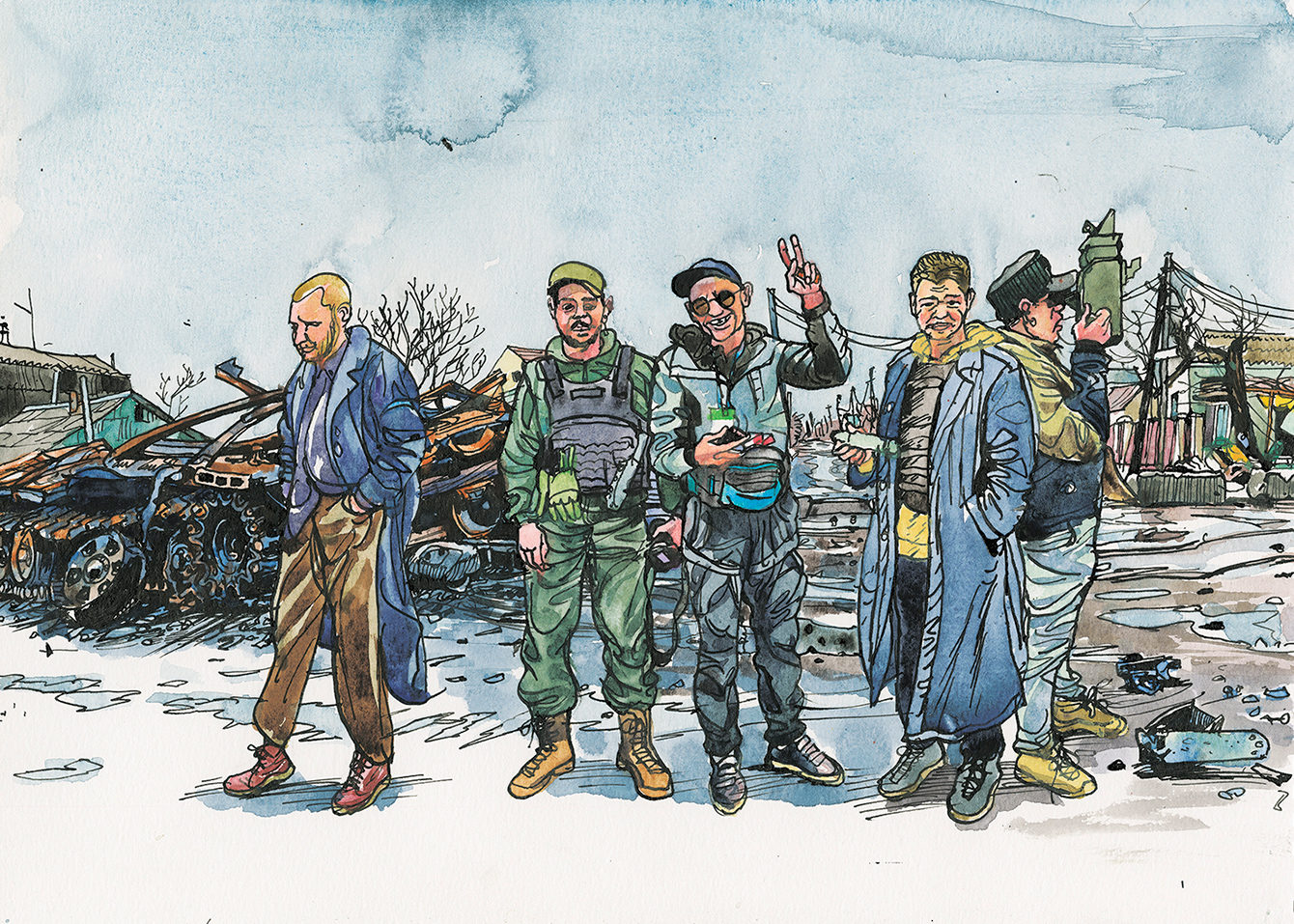

A patrol of Ukrainian soldiers stopped alongside us in a convoy of mud-washed Nissan pickups and took photos of the dead man. One of them scrambled up the cannon to get a close-up of his blistered, bloodied face. The other soldiers prowled around the dislocated turret in balaclavas and kneepads, recording videos on their phones. In another burnt-out vehicle, a gutted armored personnel carrier, they found the carbonized husk of a headless Russian’s torso.

One of the Ukrainian soldiers—a sniper, to judge by his rifle—had on a newsboy cap and a nice watch. Another had long hair and plug earrings. It was the closest I had been to regular Ukrainian army infantrymen, and though I was weary of pestering everyone about Americans, it was finally my chance to ask real frontline fighters about the International Legion.

The soldier in the newsboy hat didn’t seem to understand me. His long-haired comrade remembered Zelensky’s announcement, but the only foreigners he had seen in the army were Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians. “I hear about it,” he said in English, “but I never meet it in real life.” They ran off to catch up with their departing convoy, and I watched them drive north toward Bucha, where the first confirmed reports of mass graves had just emerged. The next day, the government would declare the whole region liberated. The battle for Kyiv was over, and so was my hunt for traces of the International Legion. I was convinced that it was more myth than reality, and that the role of foreign volunteers in the defense of the capital had been virtually nil. Eager as Westerners were to fight in Ukraine, it was plain that they were not needed.