Malaga Girl, Navigation of Bones, by Daniel Minter © The artist. Courtesy Greenhut Galleries, Portland, Maine

Like William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County or Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, Paul Harding’s imaginary New England town of Enon is repeatedly evoked in his work, giving its name to his second novel and playing a significant role in his latest, This Other Eden (W. W. Norton, $28). The title refers to somewhere new: Apple Island, off the coast of Maine. Apple Island is based on Malaga Island, which, a brief epigraph explains, was “home to a mixed-race fishing community from the mid-1800s to 1912,” when the state evicted all forty-seven residents.

Harding—whose first novel, Tinkers, was rejected many times before being accepted by the tiny Bellevue Literary Press, winning the 2010 Pulitzer Prize and selling more than half a million copies—is a prose stylist of uncommon beauty. Like Robinson, his former teacher, he writes with the gravitas of a mythmaker. This Other Eden introduces the residents of Apple Island a year before their eviction: there is the local matriarch Esther Honey, her son Eha, and his children; the almost feral Lark family, in which husband and wife are also brother and sister; the hardy McDermott sisters and their adopted Penobscot children; and the island’s mystic, Zachary Hand to God Proverbs, who lives in a hollow oak tree. We encounter them as individuals with a complicated affection for one another, and only later come to understand how they are seen from outside: queer squatters deemed degenerate, reads a headline in the mainland’s Foxden Journal, the article “surrounded by advertisements for fig syrup, fresh mined coal, small trousers at smaller prices, and Harvard cigars.” There are also rumors of parents killing children.

To their own minds, the Honeys and other residents of Apple Island are neither squatters nor degenerate, though Zachary embraces queerness with an exuberance that’s both Whitmanesque and contemporary:

I’m queer. I’m queer for my self, for my selfhood, queer for this queer self I find myself to be, queer with strange appetites, and a heart that throbs most queerly. I’m queer for other queers, queer for their shapes and colors and sizes, queer for their tastes.

He and Esther are the island’s elders, bolstered by the story of the community’s founders, Benjamin and Patience Honey, who survived a biblical hurricane in September 1815 to establish the colony. The scene becomes one of the novel’s several magnificent set pieces:

And all the Honeys in that old tree climbed with all their strength, the children screaming and crying, the men and women screaming and crying, until the whole soaked clan clung together and to the trunk in a trembling, grasping cluster at the top of that swaying, bending, mighty old tree snapping back and forth in the wind like a whip.

In the settlement’s early days, their survival was a triumph. For Ethan, Esther’s grandson, the island is the Honeys’ “own ark”; for Esther, the evictions, when they come, are a return “to the wilderness.”

The pace of Harding’s storytelling is stately, his descriptions, even of small events, gorgeous. Girls eating oysters “poked the frilled, layered meat and slid it around the smooth insides of the carapaces.” Men mowing a field “worked across a translucent sash of papyrus, bright and glowing, unrolling across Ethan’s field of vision.” These are sentences to be savored, and they constitute the novel’s chief narrative pull. Dramatic action, long bruited about, comes late, though forcefully: the schoolteacher, Matthew Diamond, a mainlander who is ambivalent toward his charges, introduces the threat, and then the reality, of unwanted attention from the government. The island’s dismantling is brutal.

Diamond, though complicit in the community’s destruction, knows the particular gifts of its inhabitants. Thinking to save at least Ethan, who is artistically talented and can pass for white, Diamond arranges for the boy to live with a wealthy friend of his in Enon, and perhaps attend art school. There, Ethan will meet and fall in love with an Irish maid. The other Apple Island children, gifted in Latin and mathematics but more clearly black in appearance, will not be rescued. Yet Ethan’s life will ultimately prove no easier than theirs.

The fictitious Apple Island allows Harding to explore dark histories. Over a century, a small community of mixed-race households and, in Harding’s novel, of fluid gender identities, evolved on this tiny outcrop in the Atlantic, which was accused of being the site of incest and infanticide well before the authorities arrived. Everyone was always already fallen, Harding makes clear, even as he conveys the vastness of what was lost. This Other Eden is beautiful and agonizing—rather like the real place that inspired it.

“Landscapes for the Homeless #31,” by Anthony Hernandez © The artist. Courtesy Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York City

Tracy Kidder’s new book Rough Sleepers (Random House, $30) affords a similarly uneasy portrait of the United States, but without the potentially consoling distance of history. The number of people experiencing homelessness across America has grown in recent years, reaching 580,000 in 2020, the most recent year for which we have figures. Kidder is best known for Mountains Beyond Mountains, his bestselling book about Paul Farmer, the late founder of Partners in Health, which provides medical care to some of the poorest people in the world. With Rough Sleepers, Kidder turns his meticulous but generous eye on Jim O’Connell, another Boston doctor—indeed, another Harvard Medical School graduate—and the founding director of the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP). This organization has, since 1985, provided support in a variety of forms to Boston’s unhoused population, offering an outreach van, street clinics, and a doctor for drop-ins almost every weekday at Massachusetts General Hospital. It was the first program in the country to provide integrated care for HIV-positive patients experiencing homelessness, the first to publish a manual of common communicable diseases in shelters, and the first to establish a center for respite care for those too sick for the streets but not sick enough for the hospital.

Kidder, who met O’Connell in 2014, “followed him with a notebook” intermittently for half a decade. O’Connell went to medical school at thirty, having studied philosophy at the University of Cambridge, then worked as a teacher and a basketball coach in Hawaii and as a bartender in his native Rhode Island. After the University of Vermont implied he was too old to attend, he went to Harvard. There he was conscripted by his elders to run a new homeless health care program for which they’d received a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. He initially accepted for a limited term: one year of “giving back.”

Rough Sleepers relays not just O’Connell’s trajectory over the next thirty-five years, but that of the ever-growing BHCHP (which now has an annual budget of approximately $50 million) and its evolving community of caregivers—doctors and nurses, therapists and administrators. Among them is Barbara McInnis, a beloved nurse at the Pine Street clinic and a lay Franciscan who “believed in service and simplicity and in kindness to all creatures,” and in whose honor the respite center was named in the early Nineties, well before her unexpected death in 2003. Rough Sleepers also tells the stories of those in the homeless community O’Connell and his colleagues serve, such as Frankie, who was ordained as a minister while homeless, or Judge, “who called himself a judge” and “never abandoned the role, not even on his deathbed,” or Susie, a singer who had been part of “a band that once opened for B. B. King.” Most memorable is Tony Columbo, a former sex offender who struggles to get his life back on track. “Jim changed me,” he tells Kidder; to O’Connell he says: “I know there’s goodness in the world.”

O’Connell treats his patients not as statistics but as human beings. He is a doctor who has retained the bartender’s spirit, despite the Sisyphean nature of his mission. “Medicine is not efficient,” Kidder hears O’Connell say. “It’s not supposed to be efficient. It has nothing to do with efficiency.” His faults are that he is too polite, that he gives too much of himself. He has, a colleague says,

an attitude of pre-admiration for the people he doesn’t yet know. His presumption is, “Oh, I’m eventually going to like this person. I will probably find some reason over time to like them. I just happen not to know it yet.”

Of the countless nights he has spent riding in the van treating rough sleepers, listening to their stories, he says: “It was just a privilege to be there. I loved it.”

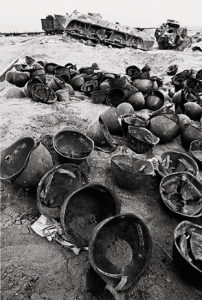

Helmets left by Soviet troops during the Soviet-Afghan War, March 1989 © Sergei Karpukhin/Reuters/Alamy

The Nobel Prize–winning writer Svetlana Alexievich, who was born in Ukraine and lived until recently in Belarus, might not claim to love listening, but there is no one more attentive. Her books, carefully edited compilations of her extensive interviews, are extraordinary: compelling, profound, and urgent. This month sees the reissue of Zinky Boys (W. W. Norton, $16.95) in Andrew Bromfield’s excellent translation from 2017. (The book has been revised since it was first published in the USSR in 1989.) It includes interviews with soldiers, medics, and civilians who participated in the Soviet–Afghan War during the Eighties, as well as with the widows and mothers of deceased soldiers. “I hate war,” she writes of the feeling that underpins her writing, “and the very idea that one human being has a right to the life of another human being.”

Near the end of Zinky Boys, Alexievich recalls overhearing someone in the early Nineties say:

The people are humiliated and poor. And not long ago we were a great power. Maybe we weren’t really like that, but we thought of ourselves as a great power . . . And we believed that we lived in the best country, the most just country. But you tell us that we lived in a different country—a terrible country, drenched in blood. Who’s going to forgive you for that?

Some thirty years later, Putin has embarked on a new war, this time in Ukraine, under similarly false pretenses, comparably unprepared. To read about what took place in Afghanistan sheds light on the situation of today’s Russian conscripts—many under the influence of government propaganda, plied with alcohol and drugs, and destined to suffer serious psychological trauma, if they survive the war. Now, however, voices like Alexievich’s have been silenced: they cannot be heard in Belarus or Russia. Under Soviet rule, she was able to publish Zinky Boys, even if she was (unsuccessfully) sued for libel. Alexievich herself has lived in Berlin since September 2020, having fled Minsk once she heard she was going to be arrested for opposing President Aleksandr Lukashenko.

The book’s title refers to the zinc coffins in which soldiers’ corpses were returned to their families (some prefer to translate the title as Boys in Zinc); but one grieving mother arguably faces something worse: her son, after returning from war, killed a man with a kitchen axe she used to trim meat, “and in the morning he brought it back and put it in the cupboard. Like an ordinary spoon or fork. I envy a mother whose son came back with no legs,” she says. “I envy all the mothers, even those whose sons are lying in their graves. I’d sit by the little mound and feel happy. I’d bring flowers.”

In 1988, Alexievich traveled to Afghanistan to see the war firsthand, and Zinky Boys includes her journal entries from the trip: “I am a historian of the untraceable,” she notes. “What happens to great events? They migrate into history, while the little ones, the ones that are most important for the little person, disappear without a trace.” Against the myth of a glorious war, she sets battlefield details: “A dead peasant farmer lying there—a scrawny body with big hands.” By the time the war ended in 1989, the idea that the Soviet Armed Forces were Afghanistan’s saviors had crumbled. “I can never be who I was before the war,” a signaler says. “How can I become a better man when I’ve seen guys buy two glasses of a hepatitis patient’s urine from a doctor for hard currency checks? Then drink it. And fall ill. And get invalided out.”

The Unwomanly Face of War, Alexievich’s first book, collected the experiences of women who served in World War II. In Afghanistan, women became matériel: “Why have thousands of women in this war?” a nurse asks. “Well, you understand . . . I can’t explain it genteelly. . . . So the men wouldn’t go crazy.” One woman laments: “When I meet a boy back in the Union I won’t be able to throw my arms round his neck. For them we’re all whores or madwomen.” It seems apt, then, that “the girls used to dry scorpions as souvenirs. Big fat creatures stuck on pins, like brooches, or hanging on threads.”

In December 1991, the Afghan veterans, ex-nurses, and grieving mothers witnessed the collapse of the USSR, the system they had pledged to defend. Disillusion had set in years before. “I want to know what we did to deserve this. Why did they wrap my son up in zinc?” one mother says. “I curse myself. I’m a teacher of Russian literature. I taught him: ‘Duty is duty, son. It’s what you have to do.’ And in the morning I run to the grave and beg forgiveness.” Alexievich has been celebrated for inventing the “novel in voices,” taking up to a decade to make each book from interviews with three to five hundred people, conversations that are taped then transcribed, reworked in longhand and rehearsed like monologues. But the voices were always in service of something bigger: “Everybody wants to forget Afghanistan. To forget these mothers, forget the cripples,” Alexievich wrote in 1993. “Forgetting is also a form of lying.”