Self-Portrait, 1901, by Pablo Picasso © 2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society, New York City/Musée National Picasso-Paris

Picasso is to art as Kleenex is to tissues. Few artists have achieved as much renown: his work, in its extraordinary range and vitality, is simultaneously familiar and unfathomable. Numerous biographies have been written—among them John Richardson’s magisterial four-volume account—a fact that makes one question the necessity of another five hundred pages covering seemingly well-trodden ground. But Annie Cohen-Solal’s Picasso the Foreigner (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35), ably translated by Sam Taylor, manages to approach the great artist from a new and revealing perspective. Cohen-Solal, a French cultural historian whose 1985 biography of Sartre remains a landmark, has mined archives—Picasso’s as well as those of the French government and the Paris police—to trace how the artist’s international fame was established even as he was largely ignored by the august institutions of his adopted country, and how some of his seemingly indecipherable actions can be explained by his position as an outsider in a xenophobic society “obsessed with the idea of a national cultural purity.”

Pablo Ruiz Picasso, son of the dean of Barcelona’s École des Beaux-Arts, arrived in Paris in 1900 just before his nineteenth birthday. Poor and ambitious, he lived on the margins, bolstered by fellow Catalans whose anarchist politics made them targets of the police. Surrounded by a “world of poverty and exhaustion,” he painted “flamboyant dwarfs, glassy-eyed morphine addicts, flirtatious old women wearing too much makeup, mothers wearily dragging their children behind them.” Picasso would remember this community of outsiders, keeping a bottle of absinthe a friend gave him in the freezing winter of 1907–08, when shards of ice floated in the Seine and he couldn’t afford canvases or paint.

Picasso was recognized as a genius very early on: he invented Cubism in collaboration with Georges Braque; participated in pivotal exhibitions in Paris, London, and New York; designed sets and costumes for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes; and allied himself, in the early Twenties, with the Dadaists and the Surrealists. He repeatedly transformed the avant-garde in his first twenty-five years on the scene, all the while rivaling, then surpassing, Henri Matisse in critical regard. But Cohen-Solal makes it clear that Picasso’s supporters were, like himself, largely outsiders—foreigners and Jews, such as his German-born art dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler; his first collectors, the Americans Gertrude and Leo Stein; the Czech Vincenc Kramár; and the Russian Sergei Shchukin. During the First World War, Kahnweiler’s assets were confiscated, among them close to seven hundred of Picasso’s early works, which would not be seen again until the government sold the collection at auction.

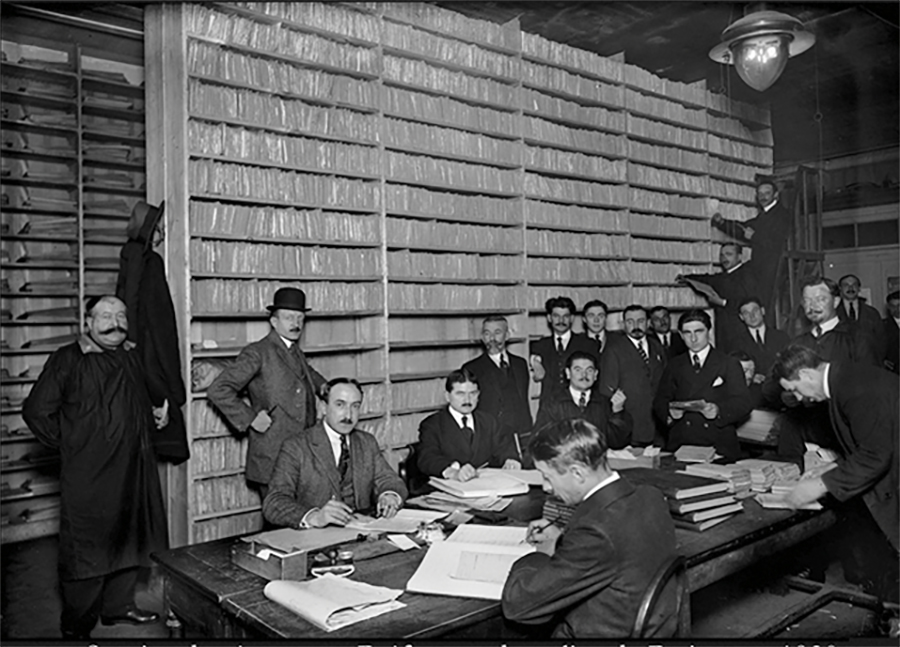

The Paris Police Prefecture, circa 1920 © Roger-Viollet. Both courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Picasso’s friendships, during the war and afterward—with Jean Cocteau (who introduced him to Diaghilev) and subsequently with aristocrats such as Count Étienne de Beaumont—have struck many as surprising. But Cohen-Solal suggests that, in that period, the bourgeoisie, “using institutions inherited from the ancien régime . . . decapitated the avant-garde,” while aristocrats “would engage in cultural subversion within French society.” The implication is that Picasso played, for much of his long life, a strategic game in which he attempted to safeguard his artistic freedom while also trying to improve his precarious status as a foreigner. For decades, French institutions refused to collect his work. In 1929, when the Louvre chose not to acquire Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (which has belonged to the Museum of Modern Art since 1939), only two of Picasso’s works were held in French museums: one in the Jeu de Paume in Paris, and the other, a gift from the artist, in the Musée de Grenoble.

Near the beginning of World War II, Picasso applied for French citizenship via naturalization. Effectively exiled from Franco’s Spain in 1937 for painting Guernica, he had also been labeled a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis. Cohen-Solal’s is the first biography to trace the failure of Picasso’s application, and reveals his denouncer as Émile Chevalier, a “second-rate policeman” and painter with Nazi sympathies. Cocteau and others, including Germans, protected Picasso during the war, which he spent between Royan and Antibes in the south of France and in his Left Bank studio on the Rue des Grands-Augustins.

Once Paris was liberated in 1944, Picasso joined the Communist Party—an affiliation that would prohibit him from visiting the United States, though Alfred Barr, the founding director of MoMA, managed to cement his reputation here. “Few could discern Picasso’s threefold otherness in French society—foreigner, politically engaged intellectual, avant-garde artist,” Cohen-Solal asserts. Becoming a member of the French Communist Party “brought an end to all these worries,” turning his precarious standing into an asset: “In joining the party,” she writes, “he also glorified his status as a foreigner.” Picasso lived for roughly three decades after the war, through periods of remarkable creative expansion, including in other media besides painting, such as ceramics. “In contrast to all those artists who shrink in ambition as they get old, Picasso extended his,” Cohen-Solal writes. Her book makes the compelling case that Picasso’s status as an outsider was integral to his genius for boundary breaking.

Tomato harvest in Firebaugh, California, 2014 © Matt Black/Magnum Photos

A newly translated novel from the late Hungarian writer Magda Szabó, The Fawn (NYRB Classics, $17.95), splendidly rendered by Len Rix, takes a rather more jaded view of the Communist Party. Szabó’s non-doctrinaire poetry won the Baumgarten Prize in 1949, only for the prize to be rescinded the same day: the Communists had taken power and she was now an enemy of the people. She couldn’t publish anything for seven years. Her first novel, Fresco, came out in 1958, followed by The Fawn. She would publish several more novels in Hungary, as well as plays, memoir, and stories for children, but only became known internationally with the publication of The Door in 1987. The Fawn, among other themes, animates the falsehoods of the Communist narrative.

Eszter Encsy, the novel’s narrator, is a popular stage actress in Budapest; her success, she tells us, stems partly from her decision to “completely extricate” herself from her upper-class background. We learn, though, that the narrative of her privileged childhood is an utter lie. “The story grew with every telling; in the last one I concocted I had a horse all of my own, I used to ride him on the family estate.”

Eszter was born into an aristocratic family fallen on hard times, who moved to ever smaller and more squalid quarters throughout her childhood, because her father, known as “the mad lawyer,” declined to take clients, preferring to feed crumbs to insects and talk to plants. Her mother supported the family by giving piano lessons; Eszter served as a housekeeper and scullery maid. Though she had a scholarship to attend a school founded by her great-grandfather, Eszter’s parents didn’t have enough money for her uniform, or even for new shoes; instead, Eszter wore a pair donated by her aunt, whose feet were smaller than hers, causing permanent damage. Eszter’s upbringing is rife with suchparadoxes, pervaded with deprivation and a primal rage at her circumstances. Her girlhood is a litany of loss: of her gentle father; of her family home, bombed during the war; and of much else besides.

When a new girl, Angéla, moves to town with her prosperous family, Eszter finds an object for her wrath. Rich, beautiful, generous to a fault, Angéla is Eszter’s nemesis:

She really loved me. She loved all my mother’s family; she loved our house, even the lilac curtain in the kitchen and my shoes with no toes. . . . She attached herself to me as sincerely as I hated her.

Resurfacing in Eszter’s adult life, Angéla is no less despised than in childhood: the players are familiar, but their significance is radically altered. Now Eszter is in love with Angéla’s husband, a scholar and translator of Shakespeare to whom Eszter addresses the novel.

Szabó has created a character of defiant complexity and perverse, utterly plausible self-destructiveness. Eszter’s childhood, marked by poverty and neglect, has made her not just angry but self-hating, suspicious of affection and determinedly independent, deploying her many masks not simply to protect but to replace her innermost self. The Fawn refuses any clear political agenda: intimate, contradictory, elusive, Eszter’s confession to her lover resists coherent—official!—narrative. Szabó’s psychological acuity, amply on display in her later novels, is thoroughly present here too, despite the novel’s reliance on febrile midcentury melodrama. Eszter’s early trauma threatens any chance of happiness; just as the looking-glass reversals of the Communist agenda publicly transform pampered Angéla into a solemn folk hero, Eszter is weighed down with the burden of a privilege she never actually knew.

“Ondria Tanner and Her Grandmother Window-shopping, Mobile, Alabama, 1956,” by Gordon Parks © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation. From the expanded edition of Gordon Parks: Segregation Story, which was published last year by Steidl

The contradictions of contemporary American capitalism, though of a different sort to those of midcentury European communism, are no less stark. Roughly one in nine Americans live in poverty. If the American poor “founded a country, that country would have a bigger population than Australia or Venezuela,” Matthew Desmond notes in his new book Poverty, by America (Crown, $28). Author of the 2017 Pulitzer Prize winner Evicted, Desmond returns with a lucid and scathing explanation for one of our nation’s abiding injustices. “Tens of millions of Americans do not end up poor by a mistake of history or personal conduct,” he writes. “Poverty persists because some wish and will it to.”

Whereas Evicted was structured around the stories of eight poor families and two landlords in Milwaukee, Desmond’s new book is primarily a polemic. It is impeccably researched and bolstered by seventy-six pages of dense notes—those seeking further source material will certainly find it—but Desmond wishes to influence a broad swath of American readers, not an academic coterie. He asks: “Are we—we the secure, the insured, the housed, the college educated, the protected, the lucky—connected to all this needless suffering? ” The answer, unsurprisingly, is yes.

That poverty is not simply a lack of money but an accumulation of issues that attend it—including pain, instability, fear, the loss of liberty, alienation, shame, and diminished personhood—may seem obvious, but merits repeating. This book contains shocking statistics, among them that the wealth gap between black and white families hasn’t changed since the Sixties. The discrepancy is shocking: The median white household in 2019 had nearly eight times the wealth of a black one. Education has little effect on this, as the average white household headed by someone with a high school diploma is still wealthier than a black one headed by a degree-holder. The decline of unions has left workers without bargaining power, meaning that some of the lowest wages in the industrialized world are to be found in the United States, and that most of our working poor are thirty-five or older. Within the past half-century, the salaries of the One Percent nearly doubled, while the wages of most earners stagnated.

Though the United States is second only to France in its welfare spending (itself a stunning revelation), Desmond shows that “the biggest beneficiaries of federal aid are affluent families.” Families in poverty received 22 cents for every dollar allocated to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program in 2020. Roughly seven million low-income workers entitled to the Earned Income Tax Credit don’t claim it, leaving $17.3 billion on the table. Meanwhile, tax breaks for homeowners—a form of government aid that is automatic rather than applied for—saved $15.5 billion for those with incomes above $200,000 in 2020, but only $4 million for those with incomes below $20,000. “In many corners of America, a pricey mortgage doesn’t just buy a home,” Desmond points out, “it also buys a good education, a well-run soccer league, and public safety so thick and expected it appears natural.”

“War on the Benighted #2,” by L. Kasimu Harris © The artist. Courtesy the Collection of Drs. Joia and Andre Perry

James Baldwin observed in 1960 how “extremely expensive it is to be poor.” Rents in less tony neighborhoods are only fractionally lower than those elsewhere, forcing inhabitants to spend a much higher percentage of their income on housing. They also pay for the exorbitant costs of what Desmond terms “the fringe banking industry,” the only option for those with bad or no credit. “Four in five payday loans are rolled over or renewed,” Desmond notes, meaning that it costs, on average, $520 in fees to borrow $375. From these facts alone, the spiral of debt and despair awaiting anyone living near the poverty line is brutally apparent.

What can be done about this? Poverty, by America challenges the myth that raising the minimum wage will hamper growth. Desmond advocates for modern unions (meaning ones more welcoming to women and people of color); he calls for regulated bank fees, expanded housing access, universal health care, and reproductive choice. He criticizes corporations and lobbyists, and those who shop or invest without first conducting due diligence (which is most of us). “If a company has a record of tax evasion, union busting, and low pay, it is an exploitative company,” he writes. “We shouldn’t be their customers or their shareholders.” All of us can be “poverty abolitionists,” and he exhorts those who make concerted choices to “brag about it,” because “it’s easier to change norms than beliefs.” And crucially, he calls for an end to community segregation:

When families across the class spectrum send their children to the same schools, picnic in the same parks, and walk the same streets, those families are equally invested in those schools, those parks, those streets.

Desmond’s book makes an urgent and unignorable appeal to our national conscience, one that has been quietly eroded over decades of increasing personal consumption and untiring corporate greed. “What we cannot do,” he writes, “is look the American poor in the face and say, We’d love to help you, but we just can’t afford to, because that is a lie.” Instead, we must ask ourselves, “Is this the capitalism we want, the capitalism we deserve?”