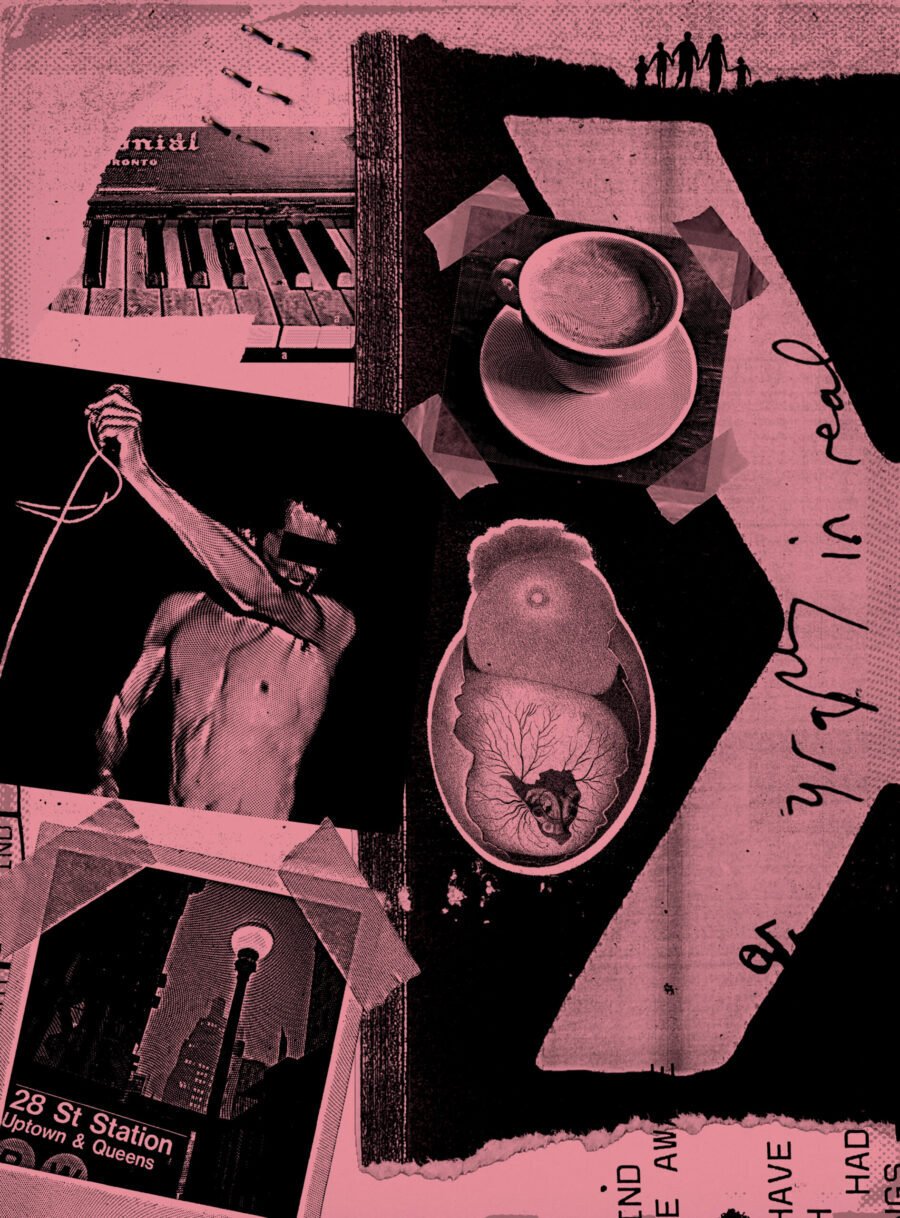

Collages by Jimmy Turrell

I recall having breakfast at a hotel in Brussels in 2017 and sitting across from Douglas Coupland, the author of Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, the 1991 book that gave my generation a sort of name that was really only a placeholder for a name. I wanted to tell him how much I resented him for this, but I couldn’t muster the courage to be disagreeable.

At the time it was my firm belief that generations did not exist, that they were simply a retroactive periodization that imposed narrative cohesion on history, one which had really no more legitimacy than such contested categories as “the Dark Ages” or “postmodernity.” “Generation,” of course, means primarily sexual generation—think, for example, of Aristotle’s treatise On the Generation of Animals—and for a long time I bristled at the thought that my own individual generation, in Aristotle’s sense, could also, at the same time, be part of a vastly larger collective generation: the coming-into-being of millions of us at once, or in roughly the same period, millions who, as coevals, share much of the same nature and the same fate. This felt like an echo of astrology. What do I, who am sui generis (note here the reappearance of the Latin root in question), have to do with those who were born in approximately the same epoch?

It was around the time of that breakfast in Brussels that everything began to sink in for me, even if I still refused to see it. I was well into my forties, and dimly aware that there were by now a few billion people in the world leading full lives of their own, who would consider anything I had to say irrelevant simply by virtue of the fact that it was coming from an “old” person. And yet I was still stubbornly churning out thoughts as if they had some absolute meaning independent of the age and the perceived generational affiliation of the person they were coming from. I had not yet fully admitted to myself that the world belonged to young people now—who plainly did not belong to my universe of values and did not share my points of reference—and that from here on out my presence was, at best, to be tolerated.

Five years later I experience my life, most of the time, as a ghost. I see my psychiatrist and try to convince him that I am suffering symptoms of what is clinically known as “derealization.” I sit at home, and I read and write, and I literally have trouble comprehending that the world still exists. Sometimes I put on headphones and listen to music, and that brings it back again. But that transcendent world and this low one, the one in which this ghost continues to dwell, do not overlap.

My psychiatrist tells me this feeling is normal, that it is at worst a “midlife crisis” and not a full-fledged psychotic break. But it is significant that I and others of my generation have had to bear the peculiar double load of arriving at this treacherous period of the life cycle at precisely the same moment that people of all ages recognize to be a time of great cultural and political upheaval. Personal biography and world history have aligned in what seems far too perfect an annihilation of almost everything that once oriented us: a belief inherited from our hippie parents that our libidinous selves were nothing to be ashamed of, and that we would be free to live out our days, as Czesław Miłosz put it, “under orders from the erotic imagination”; a more or less confident acceptance of the durability of liberal democracy; a belief in the eternal autonomy of art as a source of meaning independent of its quantifiable impact, its virality, or its purchase price; a belief in the ideal of self-cultivation as a balance between authenticity and irony; a belief that rock and roll would never die.

I mean that last bit literally. I want to talk about my generation, but in order to do that I must first talk about music. For I can find no other way in.

It is perhaps our first and most primitive experience of time: an ordering of moments on the downbeat. Nor, it seems to me, could there be any memory of the past without memory of musical experience, nor any coming to consciousness without musical consciousness. Could I have begun to think the thoughts that I do had I not first apprehended the structure of the world in song?

It started modestly, as one might expect. Lullabies gave way to Sesame Street rhymes and Mr. Rogers records checked out from the library and played on a Fisher-Price turntable. On our cross-country trip in the back seat of my grandparents’ orange AMC Hornet station wagon that smelled of burnt butter, my big sister and I fondled our bicentennial trinkets from Mount Rushmore, and to keep our knees from touching when we absentmindedly kidspread we inserted a Kleenex barrier between them. Out in the Badlands, Paul Simon’s “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” came on the radio, and we had no idea who he was, nor any sense of the real meaning of his lyrics, but we knew enough to sing them in gleeful abandon: “Slip out the back, Jack / Make a new plan, Stan,” etc. We flapped our knees like Charleston dancers, and the Kleenex fell to the ground.

So far, so passive. But slowly, some kind of active search began. Back home our parents kept a cardboard box full of eight-track cassettes high up on a shelf. Somehow I maneuvered them down, and inspected the treasures inside: Carole King’s Tapestry, Earth, Wind & Fire’s Head to the Sky, Janis Joplin’s Pearl. I flipped them reverently, and understood they were tokens of another world.

I had my first loves, which would embarrass me today if there were any time left for embarrassment. I liked the Fifties-revival act Sha Na Na, and especially the deep-voiced and comical Bowzer. The boomers have tried to write Sha Na Na out of the history of Woodstock, but I have the original triple album and I know the truth: they were there. I liked Kenny Rogers too. For my tenth birthday I got to see him live—my first real concert. I was disappointed when Dolly Parton was brought out for a surprise appearance in a green sequined evening gown with extreme décolleté, and the crowd whooped and hollered and muttered, as one did back then, about the size of her breasts. I just wanted more Kenny.

My father, curiously also named Kenny, tolerated these childish tastes while leading by example, passing down to me, without being pushy about it, Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, some Grateful Dead, Herbie Hancock. I remained under his tutelage after the divorce, when he set up his new bachelor condo with a Sony stereo set that included our first CD player, which he outfitted with Pink Floyd’s The Final Cut, Talking Heads’ Remain in Light, Steely Dan’s Gaucho. I could say I “listened to these” thousands of times, but that would capture neither the underlying neuroscience nor the phenomenology of what was happening. It would be more correct to say that I was transferring them from one medium to another, from iridescent plastic disc to hidden mind, which was itself still plastic in another sense of the term, and was fundamentally shaped by what it took in, there, in the stereo corner, with the headphones on, in 1984. I can still hear these albums perfectly, from start to finish, when others around me hear only silence.

One thing about music, at least when you’re young, is that it’s never just music. My father was an adult, which meant in part that he just liked “music that’s good,” while my shift from passive inheritance to active cultivation involved a great many blind spots, and a great deal of parochialism and posturing. The musical totemism by which postwar youth consolidated their identities through affiliation with some genre or other was as real as any other social fact. Bobby-soxers, teddy boys, mods, rockers, punks, new wavers, and metalheads were governed by no board of directors or elected representatives, but these taxa constrained our range of choices nonetheless, and defined our sense of self as fully as any professional guild or political party. Circa 1985, the East German secret police compiled a full taxonomy of youth musical subcultures. An illustrated chart gave the typical age, appearance, and political orientation of their members. The skinheads had “partly neofascist tendencies,” the punks could be known by their “ ‘Iroquois’ haircut” and their “criminal conduct and asocial lifestyle,” and the goths were noteworthy for their “total political and social disinterest.”

The Stasi should perhaps be commended for taking the youth as seriously as the youth took themselves. Back home in Central California, we had to work the taxonomy out on our own. At the rear of the semi-rural house where my mother stayed after the divorce, a defunct chicken farm passed down by her parents, our property abutted the lot of a new Pentecostal church, separated from us by a barbed-wire fence. The pastor had daughters who used to come up to the fence to talk to us, intent on laying out the reasons we were bound for hell. When some friends of mine came over, we got the idea to go out to the field to see the girls, and to bring along a soundtrack. We had no portable electronics other than a set of Radio Shack walkie-talkies, so we placed one in front of a cassette player inside the house, and brought the other out with us—and in this way the girls who preached hellfire, channeling their dad, got a dim and squeaky rendition of Ozzy Osbourne’s Bark at the Moon channeled back at them.

The heavy-metal posture was a onetime thing for me, dictated by circumstance. For the most part my efforts at sculpting a musical identity were fueled by an esotericism that disdained common and easily accessible genres. I can see now that this was all largely epiphenomenal to a deeper and “more real” navigation of class identity. I was surrounded in those years mostly by poor white metalheads—a Judas Priest T-shirt, feathered hair, and acne were the default traits of the human male—while at the same time belonging to a white middle-class family perched dangerously close to the lower-class boundary, ever in danger of slipping beneath it. Musical cultivation, in this context, was a sort of currency by which one might hope to maneuver into an imagined aristocracy through seeking out the most obscure representatives of the narrowest genre niches.

We know the identity associated with this maneuvering by various names—“alternative,” “indie,” “underground”—and by the end of the Eighties I was about as deep into it as one can go. In my freshman year of high school, a trio of Mexican-American sisters took me in, let me sit with them at lunch and protected me from the violence of other males. The sisters wore shirts testifying to their love of the Ramones, Joy Division, the Smiths. They wore creepers and safety-pinned pants. They had an older friend named Larry, out of high school already, who swung by sometimes and delivered mixtapes with some of the most transcendent and recherché sounds I have ever heard, even to this day. He had grown up in part on a reservation, and loved Afrobeat, free jazz, and the Chicano rock he absorbed in his family milieu as much as he loved Gang of Four and the Slits. He was a musical encyclopedist; he still is, in fact, and has risen to local-legend status in Sacramento for his long career as a DJ and record store maven.

Somehow I veered off for a while, in the opposite direction, and I take this now to be a consequence of my unconscious class striving, inherited from anxious middle-class parents. By the end of the Eighties I hated everything, or at least anything that had any real prospect of being liked by more than a handful of others. My friends and I eschewed anything with the most basic musical elements of melody, harmony, or rhythm in favor of “noise.” Some of us made a big show of listening to nothing but radio static for weeks at a time in order to cleanse ourselves. Some made cassette tapes of the harshest sounds that could be conjured and exchanged them by mail with cats from Japan, a mythical homeland with what seemed an infinite supply of inscrutable weirdos. We hated guitars, and anything that repeated, even in a novel way, the old tropes from what we saw as the already sclerotic tradition of rock and roll. We rolled our eyes and pretended to hate what Kurt Cobain had to offer when Nirvana stopped off at our local haunt, the Cattle Club, on their tours up and down the West Coast (though secretly I found their performances very powerful).

Then I went to New York for graduate school, and the Nineties were all about Morton Feldman and Pierre Schaeffer and other avant-garde opportunities for the display of marathon patience. With my new cohort of friends I sought out performances that might involve a pianist slamming down his instrument’s lid or shouting “Ha!” after a long silence, presumably according to instructions given on the sheet music. We were inspired by Theodor Adorno’s idea that if music is to be considered art, and is to be a veracious witness to its era, it must ipso facto be difficult. We ordered CDs from labels in Maastricht and Berlin that promised us “clicks and cuts,” “sonic rhizomes,” and something they called “glitches,” which were for a while hailed as the equivalent to turntable scratches, but unlike scratching vinyl, which made early hip-hop continuous with the deconstructive aesthetics of the cut-up, the manipulation of a damaged compact disc sounds like nothing but an error, like a new technology that has gotten stuck.

It is hard to say when exactly this haughty farce came to an end and my current sensibility set in, a sensibility that declares, quite simply, that all music, insofar as it is music, is good. Nirvana is good, Santana is good, and Kylie Minogue is good when you’re in the back of a taxi at night in Baku (for example). It’s all good, for it all comes down to us from a higher world. I was well into adulthood, certainly, when I admitted this, well into the present century. I suppose the farce ended when the regime that had supported my imagined aristocracy collapsed, which is really just another way of saying that it ended when my generation was usurped by the next one.

Even if, for a while, I feigned hatred of rock and roll, that only made sense on the presumption of its continued reign. Much the same could be said about liberal democracy. Today, American global hegemony looks like nothing more than a desperate reprisal of a role that must be ceded sooner or later; gone is the possibility of taking it for granted in view of the supposed universality of the American empire’s soft-power export products, not least rock and roll. We’ve still got the Pax Americana here in Europe, where I live and teach philosophy, but it’s mostly just the U.S. defense establishment propping it up. Meanwhile, McDonald’s has closed on Red Square and has been thoroughly indigenized as McCafé in France; Coca-Cola disguises itself behind the labels of sundry local beverages; and Hollywood now makes its movies largely with an eye toward getting past the Chinese censors.

As for eros, it is certain that my testosterone levels have plummeted over the past decade, and that this would have been unavoidable no matter the state of the world. Yet here again we find an almost too-elegant alignment between self and world, between endocrinology and politics, as if my hormones adjusted themselves as biofeedback to our new global order, which, to say the least, no longer wishes to hear about the plight of libidinous aging males.

So my psychiatrist gives me pills. I nod along to his explanations and silently go on believing that I am a ghost. He seems to be in his mid-thirties, and in any case he is French. Who knows what the world looks like to him?

Throughout the Eighties I took 1976 to be a sort of Year Zero, the moment when the world as I knew it came into being. It is hard to say what exactly changed then. I suppose it marked the start of our transition from the aesthetics of the floppy and shaggy to the jagged and angular. This was David Bowie’s Thin White Duke phase (when he also enthused in public about the Nazis). It was when Kraftwerk landed on their iconic look and sound, and made us forget that even they had begun with sideburns, bell-bottoms, and guitar-driven psychedelia. Within a few years, the post-punk, new wave, hardcore, and gothic subgenres would all emerge, which together defined the golden age of my own musical experience. I now see that much of this era’s sensibility was in fact a recovery of the interwar avant-garde, which explains in part its flirtation with fascist symbolism. Many of the names that my ignorant friends and I took to be the trademarks of our scintillating new age were in fact only the retrieval of earlier and objectively more radical experiments (Bauhaus, Cabaret Voltaire), or at least were meant to sound like they were (Spandau Ballet, The Wolfgang Press).

I now think that the period from, say, 1976 to 1990, when music meant the most to me, was not the apex of postwar culture but in fact the beginning of its long moribund phase. We often blame Reaganism and Thatcherism for ushering in a new culture of greed that figured out ways to profit off of youthful exuberance and to process it into a mere exuberance-themed consumer product. Some musicians’ careers seem to chart this broader shift with surprising exactness: thus we have the last glimpse of Bowie’s neo-Weimar avant-gardism in the singularly great “Ashes to Ashes” in 1980, only to find him reappearing three years later with the irredeemably dorky “Let’s Dance,” a song that, along with its accompanying video, is indistinguishable from a television advertisement. From that point on, Bowie’s most significant innovations would not be in music or fashion but in finance, with a new form of asset-backed securities, “Bowie Bonds,” sold to Prudential Insurance. This is perhaps the most extreme and literal instance of “selling out” that we might adduce, and it is appropriate given Bowie’s grandiose career that even his selling out should have been so spectacular.

“Let’s Dance” was released the same year that plans for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame were introduced, a process of institutionalization and domestication that culminated in my generation’s comical mishearing of Huey Lewis’s desperate insistence in 1983 that “the heart of rock and roll is still beating” as if he were in a municipal tourism board’s advertisement enticing us to visit, shall we say, a less-than-obvious destination: “The heart of rock and roll is in Cleveland.” By the Eighties, capitalism had grown remarkably adept at taking explosive new arts and turning them into family fun, spinning a whole galaxy of new commodities off of an original product, in the form of T-shirts and key chains, opening theme parks and other sites of postmodern pilgrimage. Rock music was only just beginning this transition, while other art forms were so far along that no one could recall what they had once meant. Disney in particular was by then synonymous with wholesomeness, even if we knew that its theme parks were Potemkin villages of worker exploitation and state-of-the-art surveillance. My sister was turned away from Disneyland circa 1989 for wearing a sailing-camp T-shirt with a mild sexual innuendo about the wind (noting, namely, that it “blows”).

This image of wholesomeness, this “Disneyfication” of Disney itself, papered over the raw transgression of the generation of prewar cartoons to which the earliest Disney creations belonged. Steamboat Willie inhabited a universe of unrelenting Sadean cruelty, where cats are twirled in the air and ducks are squeezed like bagpipes for the sheer pleasure of the music that comes out of them. Willie’s was also a mostly rural and preindustrial world, where the familiarity with animals and farmwork that are assumed on the part of the viewer harmonizes with the parallel presumption of a thoroughgoing pananimism of the sort the cartoon animation brings to life so well. That rock and roll was getting Disneyfied, too, and enshrined in the heart of America’s ultimate postindustrial city was really just a condition of its survival in any form under finance capitalism.

This cannot all be blamed on Reagan and Thatcher. Over the course of the Eighties we witnessed the completion of a process of transformation by which hippies became yuppies, as memorialized in 1983’s The Big Chill, and the parallel evolution of Sixties counterculture into the culture of what was starting to be denoted, synecdochically, as “Silicon Valley.” Stewart Brand is perhaps the most perfect embodiment of this transition: from his beginnings as publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog, which in the Seventies I brought down from the upper shelves (next to the eight-tracks) in order to look at pictures of nudist colonies and home births, he would help to shape the organizational principles of the nascent internet culture, and, most importantly, of Apple. The fact that capitalism’s most advanced experiments by the end of the twentieth century were spearheaded by people with a lingering sense of countercultural identity helped this economic order to become particularly adept at reuptake, at incorporating cultural expressions that were first made in some sort of spirit of opposition. In 1987, the Beatles’s “Revolution” was featured in an advertisement for Nike. By 1995, Janis Joplin’s ghost voice was made to sing “Lord won’t you buy me a Mercedes-Benz” in a Mercedes-Benz commercial. And somehow, by then, Apple had managed to trademark the legacy of the Sixties as a key element of its corporate image.

It seems, now, that the historical meaning of Gen X’s famous aversion to selling out cannot really be understood without considering the world that was being actively created by our parents in the years of our generation’s formative experiences. We were, it seems to me now, doing our best to preserve postwar youth culture (and even interwar youth culture, as we’ve seen) against the rising force that would, soon enough, cast us into whatever came next: the world whose most important narratives are shaped by algorithms, and in which the horror of selling out no longer has any purchase at all, since the ideal of authenticity has been switched out for the hope of virality. We tried, and we failed, to save the world from our parents—that is, to reverse or at least slow down the degeneration of the hopes that they themselves had once cherished. And because we failed, we have been written out of history.

It is often remarked that there will never be a Gen X president of the United States. No one wants us to lead, or cares what we think. In political polling, American news outlets frequently move right from the boomers to the millennials. Though Coupland certainly could not have anticipated this meaning of X in 1991, it turns out that our name, or our lack of a name, fits perfectly with our general condition of invisibility. Generation X is the generation that someone might get around to assigning a real name later. Except that it’s already been more than thirty years, and the world has moved on. (Coupland himself has always been a trickster. Born in 1961, he is a youngish boomer, and does not seem to share in any of the authenticity-mongering that, alongside its partner irony, are the twin pillars of Gen X identity. At the time of our breakfast, he had recently completed an artist’s residency at something called the Google Cultural Institute in Paris, a concatenation of words that practically guarantees an eye roll from a Gen X-er like me. He doesn’t care. He’s aging well, making bank, and it’s all good.)

The aristocratic regime of my generation, who would not sell out until “selling out” was gutted of any meaning, has collapsed, yet it is survived by the surprisingly powerful rump of an earlier regime, that of our parents, who have largely forgotten, or never really understood in the first place, the power and potential of the creative forces they released into the world. It is against that rump state that millennials and their juniors express their contempt, as in the circulation of rather unsubtle memes that depict, for instance, elderly men having heart attacks, accompanied by slogans like die boomer?! Their grievance is mostly rooted in economics: the boomers hoarded all the wealth benefiting from the unprecedented blip of postwar prosperity, low housing prices, and expanding career opportunities, and now have the gall to criticize the young for still being wayward and broke at thirty.

This criticism is justified, yet it mostly gets expressed within algorithmic structures so ubiquitous, and so easily taken for granted when you cannot remember a time before they existed, that the thing that really ought to be the primary grievance of the young against the old—that they have left us imprisoned in these structures—simply gets overlooked. My own grievance against the boomers is that they betrayed their earliest intuitions, that they went and corporatized rock music, that they stopped believing in the revelatory power of the visions they had while on drugs, that they stopped defending the libido. My grievance against the millennials and younger is that they don’t seem to know, or care, that for a brief moment in the mid-to-late twentieth century these forces seemed to be delivering on the long-held hope—a hope held ever since the Ranters began ranting and the Quakers began quaking and all kinds of utopians went and founded their communes and got naked and dreamt, with Charles Fourier, of someday being able to play the piano with our feet—the long-held hope, I was saying, for human liberation.

Nothing reveals to me the totality of the context-collapse in which the younger generations pass their lives more clearly than the widespread philistinism and prissiness that prevails with regard to art. In 1984, the Cramps, a rock band that managed to distill the whole of postwar American musical and visual junk culture into a delightful camp act, released a compilation titled Bad Music for Bad People. As might be anticipated from the laws of logic, this double negation issues in something quite positive, laying bare as only real art could the implicit pathologies and terror of Fifties B-movies, the mythical otherworldliness of the Elvis archetype, the failure of the hippies to outdo the greasers who preceded them in living life lustfully. It is hard to imagine a similar use of “bad” today. Although the adjective does retain at least some of its autoantonymic versatility, as in fixed phrases like “badass,” in general we are no longer a culture capable of carrying through the dialectical maneuver whose paradigm expression is found in Run-D.M.C.’s 1986 anthem “Peter Piper”: “Not bad meaning bad but bad meaning good.” Today the dominant view, at least in elite institutions where millennials have made significant inroads, holds that the art cannot be separated from the artist, and that where the artist is bad the art therefore is bad—“bad,” that is, in a way that precludes the possibility of being “good.”

Whether in its nationalist, socialist, or post-liberal progressive variant, this attitude toward art is inherently authoritarian. It wants good art to be made by good people—or more precisely, by good representatives of the relevant nation, social class, or identity—and because this is generally just not how things work out, it has to do the extra work of coercion to ensure that people speak and act as if it were. The liberals, for all the deplorable whitewashing their openness required, at least typically did not see this openness as additionally requiring a liberal mirroring of socialism’s habit of propping up its official literary heroes. Nowhere is this liberal attitude expressed more perfectly than in the memorable two-part episode of the Eighties sitcom Family Ties in which the plot unfolds around a decision of one of the Keaton children to write a book report on Huckleberry Finn despite the novel having been banned by the school board for its infamous use of the N-word. The parents, tragically yuppified hippies with enduring pride in their commitment to whatever they thought the Sixties had been, insist that, beautiful or ugly, it is essential for their offspring to be exposed to the full literary record of American history.

The Keatons got something right: you do need to survey the entire history that shaped the world into which you were born in order to know who you are and where you stand. But it is a mistake to conclude from this that Huckleberry Finn is best read as a mere historical document, telling you “how they thought back then.” For Mark Twain is not “they,” and the only way you are going to be able to plumb the full depths of history, and in particular of our peculiarly American historical traumas, is by allowing at least some of the fragments of this history to work on you, on your senses and on your imagination—not only as testimonies of historical wrongs and perhaps of their eventual overcoming, but as art in the fullest sense. What is art in the fullest sense? It is impossible to give an answer that will please everyone, but we might say that it is a distillation of the spirit of its time that somehow succeeds in breaking out above its time, speaking to us across the generations in a way that transcends the limitations of its own local idiom and its own myopic present. It is shaped by its historical period but ends up saying something quite general about human suffering, human hopes, perhaps the possibility of human redemption (or not).

In order to be a suitable candidate for redemption, a being must of course be flawed. It was long thought that to be this way was simply the general condition of humanity, but today, if you were to seek to learn about our peculiar species by studying the daily tide of social-media discourse, you could easily come away with the impression that it is the condition of only some people (roughly half of them) while the rest are consistently righteous. Those who work to sustain this impression, through the daily volunteer labor of online takesmanship, tend not to use adjectives like “flawed,” “imperfect,” or “fallen.” By contrast, “problematic” has been made to do a great deal of work in the era of philistine pseudocriticism. To identify some work of art, literature, or entertainment as problematic is not overtly to seek to censor, nor to call categorically for moral condemnation. It is simply to taint public perception, to inform readers or viewers that enjoyment of the work in question will likely result in some sort of subtle social sanctioning. It is a weasel word, employed by people who lack not only the courage of their convictions but also anything beyond convictions, any of the aesthetic or moral virtues that engagement with art was, for some centuries, believed to be essential to cultivating: taste, curiosity, imagination, fellow feeling with the wretched and the fallen.

Like all Gen X-ers, I have been confronted with the absence of my own generation’s cohesion, and also, therefore, with the peculiar dilemma of having to choose the temporal direction by which I vacate the emptying space of my generation’s tenure—either forward, into the company of younger cohorts who seem unaware that they have dark depths to themselves, and appear to believe that whatever darkness remains can be clarified by rules and language reforms; or backward, to the generation born in the shadow of the Bomb, who tried to break free no matter how blindly, and to discover their own depths no matter how sloppily. For all their foolishness, they knew they had depths, and often knew, wisely, that they were fools. So there is much to cherish from their world, and for a while now I have been trying to see whether we might salvage some of that earlier generation’s legacy, and to ensure that it lives on.

Perhaps no one exemplifies the challenge of this task more fully than the cartoonist R. Crumb, who created so much of the visual template for the way we see late-Sixties and early-Seventies America. He is plainly the main character of his own work, which has had many other foci over the decades but has always been principally devoted, like all the best art brut, to the therapy of his own defects of morality and character. Yet Crumb’s art has aged with him. He has never repented, but has only observed and acknowledged the natural course of a mortal life, and changed his tack accordingly. He has never mistaken his station in the world for that of a politician or corporate spokesperson, or anyone else who has to be “on their toes” and always ready to defend, or at least to spin, their manner of expression. In the remarkable and deeply moving 1995 documentary Crumb, directed by Terry Zwigoff, our hero is at one point confronted with all the evident rottenness of his representations—all the perverted images of big-legged Amazons, all the “pickaninny” characters and other visual references to the most racist and sexist tropes of American advertising, and he declines even so much as to attempt to justify any of it. He grants that perhaps he should be “locked up,” his pencils taken away from him. His position is that it is really not a matter for him to decide what the world does with his images. He might fail to produce anything compelling; his persona might become repulsive. But he can only do what he does—he’s an artist.

This is the part that gets said. What remains unsaid, but what he seems to know, is that he, Crumb, is in fact compelling, and is likely to remain so. And he is compelling because of the history he is channelling—the fucked-up American history that coughed him out, and made him its vessel, made him speak in a new way of what it has all been about.

In an early scene of Jean-Luc Godard’s era-defining 1960 film Breathless, a character challenges Jean-Paul Belmondo, “Mister! You don’t have anything against the youth, do you?” He replies defiantly, “Yes, I do. I prefer old people.” Perhaps even more than in the immediate postwar period, we are today in the middle of a rather intense generational standoff, and virtually no one is prepared publicly to echo Belmondo’s line. It is presumed to be a betrayal of those who have a direct stake in the future, who will be around to live in it, to so much as broach the suggestion that there are dimensions of human experience they have not figured out. But this unconditional support for the youth ends up making children of us all, as it leaves us unprepared for our exposure to the raw power of subartistic entertainments that are in fact only the sugarcoating of propaganda, to the cataracts of “content” pouring out of our streams and feeds. “Content,” whatever else we may say of it, is not art. No one involved in its production, nor evidently in its consumption, appears to be interested in probing the depths of the self. On the contrary, the new system of constant cybernetic feedback-looping between content producers and “fans” is one that primarily functions to reduce entertainment products to the role of norm enforcement.

Our equivalent of socialist realism has thus slipped in through the back door: not through the top-down imposition of tyrannical laws, but through the profit-seeking of private companies that have set themselves up as the monitors and arbiters of acceptable speech. What is acceptable always turns out to be whatever makes them money, but our lived experience as subjects of this regime is substantially the same as being governed by illiberal laws. In fact it is even worse, as the government has no real power to stand up to the content-generating monoliths—something that was clear in 2020, when Mark Zuckerberg testified before a plainly clueless panel of senators tasked with investigating censorship and misinformation. Though they were seated above him in a bare spatial sense, the actual order of power in the room was inverted. Likes, retweets, upvotes, customer feedback, and algorithmic incentivization had already won out over any ideal, however imperfect, of self-government, autonomy, saying what you think, striving to know your own mind, loving the truth while always remembering how hard it is to find it.

I acknowledge that I am feeling defeated, and it is a symptom of this defeat that I have withdrawn to live in the past, like old man Crumb with his vinyl 78s of Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, hiding out somewhere in the South of France. The hard work of building an honest future—honest about what we are as human beings, the sort of honesty that simply cannot be maintained in a world without art born of freedom, and without so much as the ideal of human liberation—will have to be left to others, perhaps to a generation that has yet to be given a name.