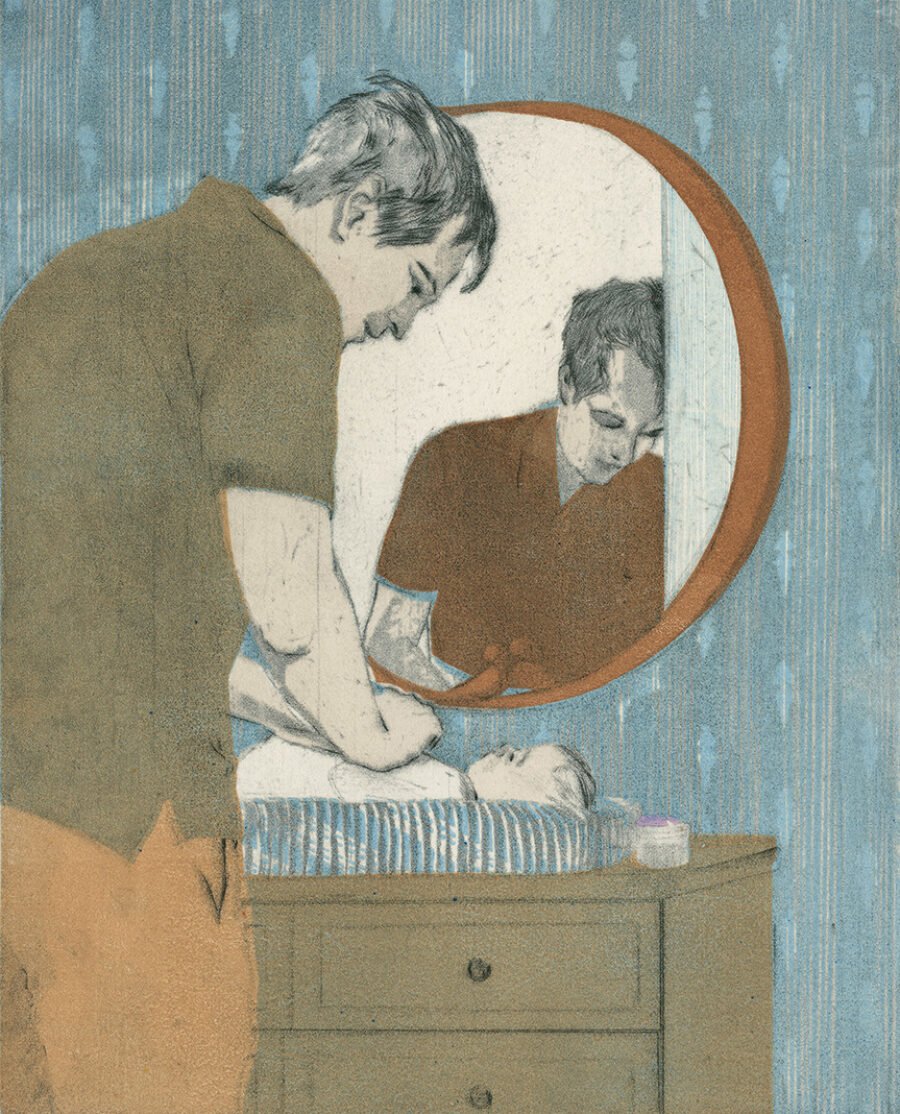

The Blue Room 5/7, by Ellen Heck. Courtesy the artist and Wally Workman Gallery, Austin, Texas

New Books

I’m a father now. Please, hold your applause. As I write this, my son is fifteen days old, and I’m staring into the soft hurricane whorl of his hair, thinking thoughts as cute, pink, and insubstantial as his little toes. With every hour we spend together, I feel, not unpleasantly, my emotional range contracting to match his own. Reduced to the purest trinity—hungry, sleepy, poopy—we will forge a lifelong bond. My mind is a rock tumbler, taking platitudes and turning them over until they’re even smoother and glossier with platitudinousness. I’ve treated my baby as an aspirational vessel, as Silas Marner did his, “an object compacted of changes and hopes that forced his thoughts onward, and carried them far away from their old eager pacing towards the same blank limit.” I’ve held a bottle to my baby’s lips at sunrise, thinking, yes, he will be America’s first king, it is written in the stars. I’ve huffed his scalp. I’ve swooned at his fine pneumatic craftsmanship, like the father in Nicholson Baker’s Room Temperature admiring his infant daughter: “Two separate vacuums—a lung vacuum for inhaling, and a mouth vacuum for sucking, were in effect simultaneously!” And I’ve feared that he’ll someday subscribe to Donald Barthelme’s creed from The Dead Father: “Fathers are like blocks of marble, giant cubes, highly polished, with veins and seams, placed squarely in your path. . . . Similar in color and texture to a slice of rare roast beef.”

All of which is to say that the arrival this month of Sarah Blaffer Hrdy’s Father Time: A Natural History of Men and Babies (Princeton University Press, $29.95) felt too fateful to ignore. I turned to it seeking validation and found something much better: the complete destabilization of my concept of paternity. An anthropologist and primatologist, Hrdy had long taken the entrenched Darwinian view that men belonged in the boardroom or the brothel more than in the nursery. Time and again, her fieldwork with apes had revealed the primate equivalent of going out for a pack of cigarettes and never coming back. Plus she was raised in the conservative Houston of the Fifties, when she can’t recall ever having seen a man change a diaper; her grandmother referred to the penis as “that projection men breed with.” In the minutes after Hrdy gave birth to her daughter, her husband “described it as ‘the happiest moment in my life’ before handing her back to me.” Men, historically, have excelled at handing babies back. In their defense, males of other species have sometimes preferred old-fashioned execution. In India, Hrdy saw male langur monkeys commit ruthless infanticides, murdering any child they hadn’t sired. “To my astonishment,” she writes, “bereaved mothers vigorously solicited sex from the same male that had just killed their baby.”

Given that “there are few, if any, records of men turning their lives over to babies the way women do,” Hrdy’s main contention surprises even her: “Inside every man,” she says, “there lurk ancient caretaking tendencies that render a man every bit as protective and nurturing as the most committed mother.” She has the proof—we’re talking about someone who once collected spit samples at a family reunion so she could measure fluctuating hormone levels. Research indicates that a man “in prolonged intimate contact with a baby” (e.g., nap time) will be flooded with oxytocin and prolactin. His brain is putty in the infant’s wee hands. “Previously quiescent hypothalamic circuits will be activated,” Hrdy writes. I’ve felt this activation, and it is good: gelatinized at four in the morning, coldcocked by my brain chemistry as my child, roughly as long as a summer squash, dozes noisily with his head against my heart.

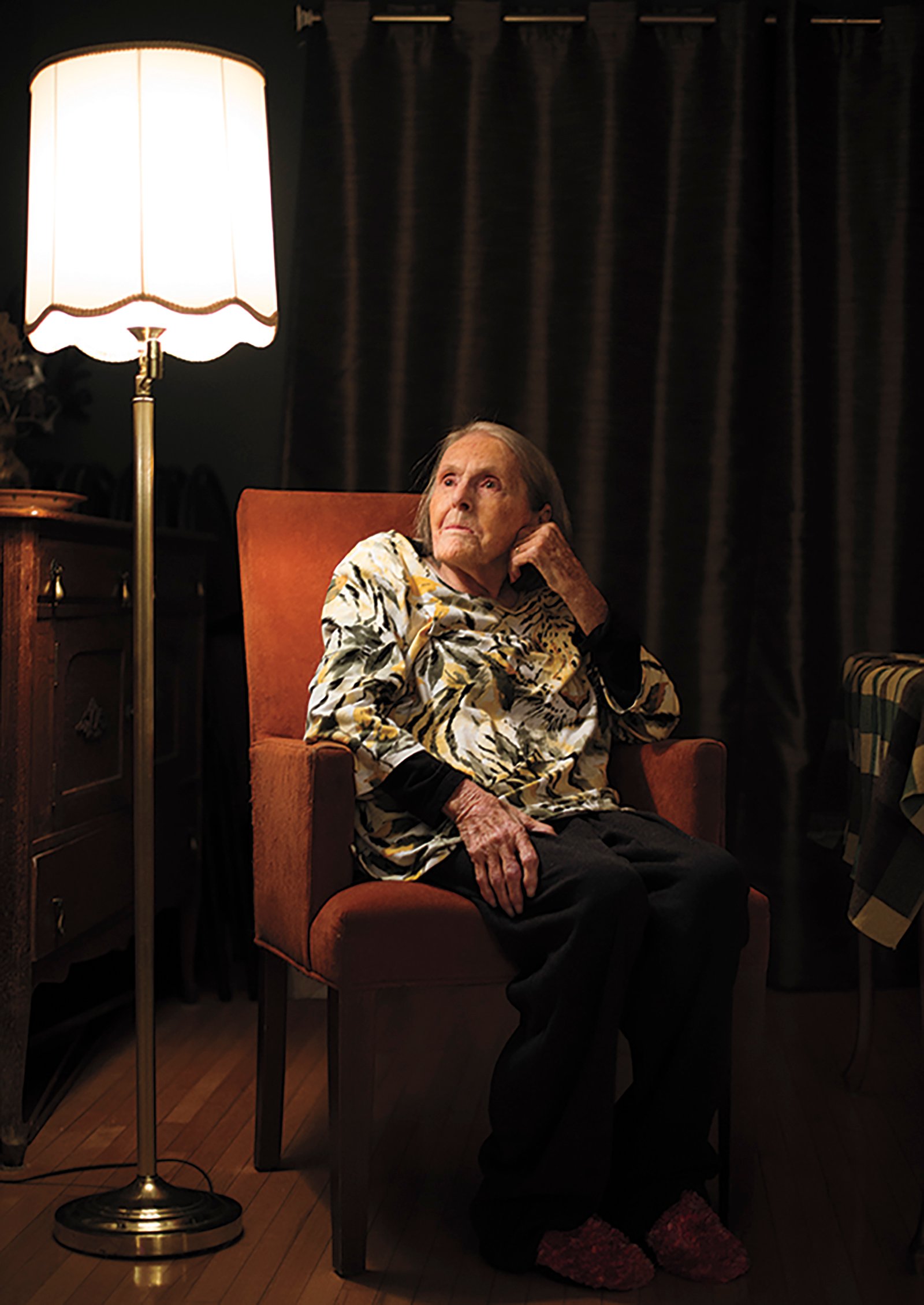

“The Beginning of Life,” by Evelyn Dragan. Courtesy the artist and Soothing Shade

If Western man has long denied himself this pleasure, it may have something to do with testosterone, which is known to decrease in new dads and has become the locus of great cultural anxiety. In many movies about fathers, you’ll notice, the child is not colicky but kidnapped: Daddy needs a jolt of that search-and-rescue T. Should our baby registries include a little something for us—anabolic steroids, maybe? Studies of fathers have generated some alarmist headlines over the years, and Hrdy has kindly collated them: no dad joke: fatherhood shrinks the brain; aw, nuts! nurturing dads have smaller testicles, study shows; in women’s tears, a chemical that says, “not tonight, dear.” In one experiment in 2012, scientists asked groups of men to hold a RealCare Baby II–Plus doll (incidentally, an early contender for my son’s name) as it cried. Those who were given amiable, consolable dolls saw a reduction in testosterone compared with those whose dolls wailed ceaselessly. The sire of a hellion, then, should feel secure in his manhood.

There are societies in which men aren’t consumed by their virility—where they’re even willing to share. In tribal Amazonia, Hrdy says, paternity is seen as “partible,” distributed among all of a mother’s sexual partners from the months preceding birth. People there are “convinced that successive ejaculations accumulate like layers of nacre building a pearl”: it takes a village. Should the child lose a dad or two, there are still others in the balance. For the Na, near the China-Tibet border, fathers merely water a seed spiritually implanted in the mother; her kin takes care of the child-rearing. Among the Sambia of Papua New Guinea, a man carrying an infant is said to slacken with impotence. He’s expected instead to perform fellatio on other men in secret rituals.

For the novitiate dad, reading parts of Father Time feels a bit like having your life narrated by David Attenborough. Suddenly you’re not just some guy with a burp cloth. You’re an exotic sample of the new natural order. Hrdy is optimistic that the twenty-first century offers a “convergence of circumstances to kiss awake”—that dads may finally pull their weight, that their days as halting, statin-swallowing absentees are at an end. We are finally expected to care, and it’s shocking that we do. Hrdy’s encomiums for her son-in-law, sprinkled throughout the book, border understandably on the erotic. He is “a remarkable baby-tending man,” a “diaper-changing, middle-of-the-night-feeding millennial,” his “shirtsleeves pushed high exposing hairy arms, as manly hands gently wiped the rose-petal softness of his newborn son’s tiny body.” Said hands are depicted in Figure 1.2; Figure 1.4 features Pete Buttigieg and his husband cradling their offspring, their hospital bands still intact. This is all agreeably unexpected—the assimilation of gentle contemporary fathers into a long and grisly anthropology. Our ancestors clubbed their competitors so we could tap the pregnant-man emoji. We’ve arrived.

Unlike dads, mothers have rarely been permitted to wander from their posts, as Hrdy learned when a colleague commenting on her work told the Boston Globe, “Sarah ought to devote more time and study and thought to raising a healthy daughter. That way misery won’t keep traveling down the generations.” It was the same story for Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey, the Food and Drug Administration medical officer who, in the Sixties, fought Big Pharma to keep thalidomide from deforming America’s babies. She prevented misery from traveling down the generations and, for her troubles, was feted less as a discerning scientist than as America’s number-one mommy. Kelsey’s biographer, Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, notes in Frances Oldham Kelsey, The FDA, and the Battle Against Thalidomide (Oxford University Press, $34.99) that “the popular media’s narrative invariably harkened to her ‘innate’ motherly instincts guiding her bureaucratic decisions.” Cold War conservatism held Kelsey up as “an affirmation that even women in the most unorthodox of roles could be assets to the nation without threatening the home.” The nanny state has rarely taken such literal form.

Prosthesis for a child affected by thalidomide, London Science Museum © mauritius images GmbH/Alamy

First available in 1957, thalidomide was a product of Chemie Grünenthal, a German drug juggernaut whose leaders included several war criminals, among them an inventor of sarin nerve gas who had been convicted of using slave labor at Auschwitz. From such unassailable minds came a sedative so safe, it was said, that you couldn’t kill yourself with it even if you tried. As Warsh reports, thalidomide was just the thing to give your kids when you wanted a night out at the pictures. In England, where it was sold as Distaval, the compound was touted as “especially suitable for infants,” a triumph over dangerous barbiturates. A “child’s life,” read one ad, “may depend on the safety of Distaval.” Indeed it did. By 1961, at least eight thousand babies across Europe had been born with maldeveloped arms or legs. Some were euthanized. Their mothers, on doctors’ orders, had taken thalidomide during pregnancy to stop morning sickness.

In the United States, Richardson-Merrell submitted thalidomide for approval to the FDA in 1960, expecting a breezy passage and plump profits. At the time, medical officers could approve drugs more easily, but rejecting them required the consent of multiple higher-ups. The New Drug Application landed with Kelsey, who was then new to the agency. She’d spent decades in pharmacology and was uniquely well-qualified for the job; she was also used to being the only woman in the room. To Richardson-Merrell’s pooh-bahs, her scrutiny seemed like the dilatory work of someone who didn’t know how the game was played. True, some of their data was shoddy. Sure, some of the clinical trials were conducted by doctors who handed out free samples and never followed up. But thalidomide was still safe . . . enough. Over the next year and a half, Kelsey kept pressing for more information while Richardson-Merrell cast her as a chiding paper pusher and, in Europe, babies came out with flippers and heart defects. By the time the company withdrew its application in 1962, the drug had been off shelves in Germany for months.

Frances Oldham Kelsey in London, Ontario, December 4, 2014 © Michelle Siu/Globe and Mail.

Then as now, the FDA was under fire for its coziness with pharmaceutical companies, so it was eager to trot out Kelsey for a victory lap. This soon devolved into a blur of ersatz feminism. An Associated Press reporter called her “a female knight in shining armor” and also “a plain Jane.” Good Housekeeping believed that thalidomide would have reached these shores were it not for her “unique combination of experience as a pharmacologist, sensitivity as a mother,” though there’s no evidence that maternal feeling factored into her decisions. Other journalists saluted her “spunk” and “female obstinacy,” while the editors of the Keystone Junior College’s Favorite Dinner Recipes of Famous Contemporary Women invited her to submit a complete menu. Had she risen to prominence more recently, it’s easy to believe that she’d join the ranks of the girlbosses, her face on mugs in museum gift shops, her name hashtagged by Hillary Clinton.

Kelsey saved countless lives and shattered the myth of the Great Physician, and her diligence ushered in sweeping reforms to the drug-approval process, but the FDA refused to give her a personal parking spot. She retired in 2005. Though Warsh’s biography is maybe too thorough for the lay reader (Kelsey’s quest for parking comes up several times), it sheds invaluable light on an agency whose pretense to objectivity has always been galling. After thalidomide, Kelsey’s next big battle was over aspartame, the artificial sweetener, which she correctly felt was rushed over the regulatory hurdles. She lost. It went straight into Diet Coke, which still tastes carcinogenic today.

“Death is our cancer,” Elias Canetti wrote in 1982, the year Diet Coke debuted. “It infects everything, it cuts into every life, it is everywhere and always possible. You reckon with it, even when you least expect to.” By then Canetti was forty years into The Book Against Death (New Directions, $19.95)—a diary of aphorisms circling the abyss, a project undertaken in the hopes that his own death would die—out now in a translation from the German by Peter Filkins. It’s one of those great books premised on its own failure, which increasingly I feel are the only books worth writing. Every page is alive with animus, ardor, humor, sufferance, with venom for death and its posturing acolytes:

Anyone who has not killed is not a man: This sentence, which Hemingway fashioned, means nothing at all. It means nothing, and above all is false. . . . Hemingway’s stupidity disgusts me more than I can say.

Memento Mori, c. 1794, by Parkin

© Ferens Art Gallery/Bridgeman Images

Appropriately, given his unswerving single-mindedness, Canetti scarcely seems to change in the decades recorded here. He begins and ends at a roar—there is no crescendo, no decrescendo, and this is a form of mastery. Year after year, you feel him railing against the immovable block of mortality, a block that comprises, as with Barthelme’s, the veined marble of the dead father. Canetti was seven when his died. “Someone who lives a long time to put off seeing again the dead father whom he fears,” he wrote in 1942, is “the definition of the lost son.” Later, in 1975: “I have never seen a picture of my father that I didn’t find absurd, never read a written word of his that I could believe.”

The new dad will find much of mordant good use in The Book Against Death, because parents die and bring their children into a world of death, and because, as Barthelme said, “the best way to approach a father is from behind.” Canetti’s own approach somewhat accelerated with the arrival of his daughter in 1972, when he was sixty-six; his words about his role in her life are among the most tender in the book.

“O my child, my child, how much longer shall I remain your father?” he wrote the following year.

I think it is the presence of my child which fills me with shyness before the prospect of death. It seems to me heinous to speak of things that would also touch upon its death. I don’t wish to burden its time, which is just beginning, with my thoughts.

He wonders if “the presence of new human beings is enough to avoid death”—an idea drenched in oxytocin. Would that Hrdy could’ve measured my hormones after I read the following: “ ‘You go to sleep,’ he says to the child, ‘but you don’t wake up again.’ ‘But I always wake up!’ the child says joyfully.” I could not have admitted this a month ago, but I cried.