Illustrations by Leland Foster

Like many, I had assumed that her name, Elizabeth Clare Prophet, was an alias or affectation. Given what I knew of her—of the strange books she wrote, of the strange church she led—it seemed a little on the nose. But in fact it was her actual married name: her second husband, Mark, came from a long line of Prophets, and Elizabeth—his soulmate, his twin flame—remained one long after his death. In a way, her first name belonged to him, too. As a child, she went by Betty Clare; Mark preferred Elizabeth, so Elizabeth she became. But Betty was how she was known to her parents and, later, to her enemies.

As for the people who knew her, who loved her, who still believed in her—they called her Mother. This is what Pamela calls her when I meet her for the first time, on Ridge Avenue in Philadelphia. The room is purple, and Pamela herself wears purple: purple pants, purple sweater, purple T-shirt beneath it. The carpet is purple, too. It is a small room, made smaller by the cloying intensity of the color and by the windows, which, while large, are mostly covered up, letting in very little light. Outside, it is a June morning, golden and warm. The effect, inside, is of being trapped in an Easter egg.

Pamela clarifies that she had two moms: the one who gave birth to her, who raised her in Pennsylvania, whom she loves so much that the thought of her makes her cry; and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, who could read minds, who summoned angels, and to whose teachings, Pamela says, she’s devoted her life. Pamela is a member and former leader of the Philadelphia chapter of the Summit Lighthouse, better known to some as the Church Universal and Triumphant, the New Age religious group that achieved notoriety under Elizabeth’s direction in the Eighties and Nineties.

In the early Nineties, the church retained an estimated membership of between thirty thousand and fifty thousand people. Church officials are cagey about numbers (this is for “spiritual reasons,” they say), but their ranks today are clearly much diminished. The church relies on donations from its members—the most serious of whom were once required to sign over their assets to the church community—as well as from the sale of books by Elizabeth like the 1984 title The Lost Years of Jesus, which, according to the church, has sold more than 250,000 copies. In its more prosperous years, the Philadelphia chapter operated out of a mansion in one of the city’s ritziest suburbs; today, its financial circumstances can be surmised from the size of its storefront church on Ridge Avenue.

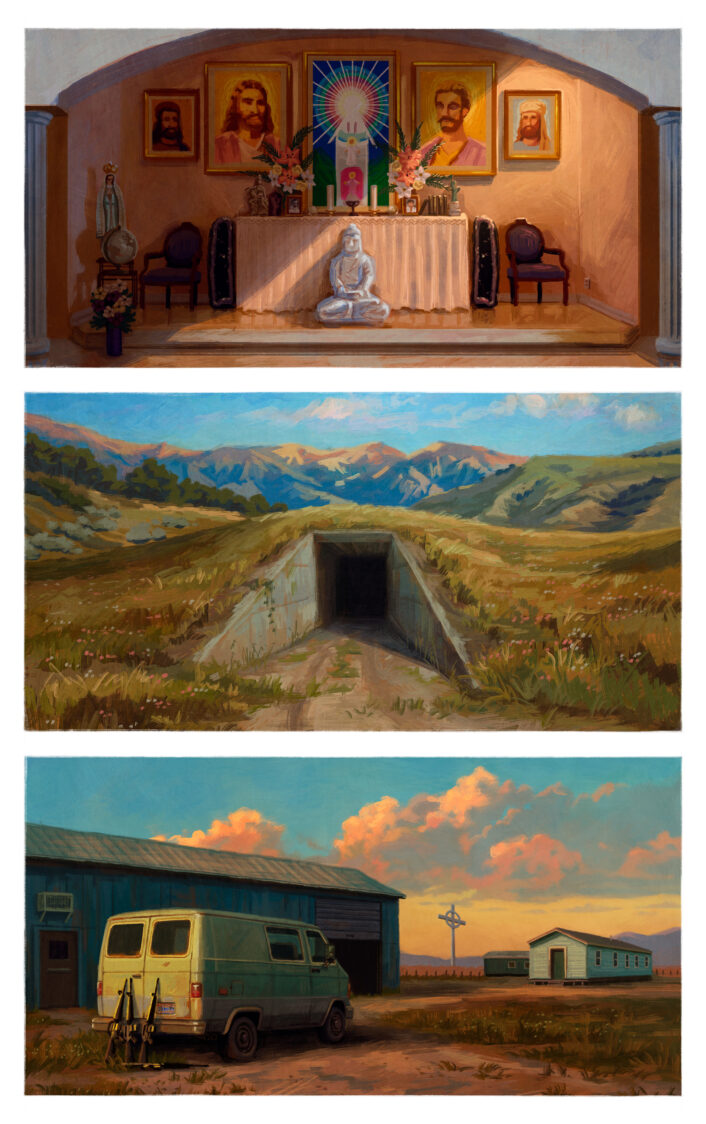

After I found Pamela on Facebook—she used a photo of Elizabeth as her profile picture—she invited me to attend Sunday services in early June last year. There, I met a handful of members of the Philadelphia chapter: Carol, Blanca, and the two Roberts. One Robert, a black man with piercing blue eyes, wore a bolo tie and cowboy boots. The other, Pamela’s husband, is white and wore a gray mustache and gray sweatpants, which he tucked into the tops of his white tube socks like pantaloons. Together, we sit and stare at the altar. Framed portraits of the Prophets stare back. Mark, pictured in black and white, has a lantern jaw and a faint resemblance to Fred Flintstone. Elizabeth, in color, looks into the camera with a knowing, close-lipped smile. Their frames are flanked by amethyst geodes. The room is so small, so brightly painted, that I feel giant and profane, an interloper in a sacred dollhouse. The lights dim; the service starts. We sit, we stand, we recite, we sing. We proceed through a dream version of a Catholic mass. In place of a homily, we have a booklet of “ashram rituals”; there are “decrees”; and rather than a priest, there’s Elizabeth Prophet, speaking to us from beyond the grave.

Twenty minutes into the service, Pamela approaches the altar and removes a cloth from a small monitor. Elizabeth appears onscreen, standing before an altar much like the one before us. Although church doctrine maintains that she has died many times—her “previous embodiments” include Guinevere, Marie Antoinette, and Martha from the Bible—Elizabeth passed away most recently in 2009. According to the church, she lives on in the “etheric realm,” as well as in some fifteen thousand hours of recordings that have for many years been stored in a concrete bunker in Montana. That footage of her channeling, chanting, lecturing, singing, and prophesying composed the bulk of her ministry. In the Eighties and Nineties, some of her followers would hand-deliver these videos to public-access TV stations. You can see the attentive faces of her devotees when the camera pans from Elizabeth to the audience in the packed ballroom. They look nothing like the dregs of the counterculture, as they were often characterized. They’re wearing slacks and enormous glasses. They look like salespeople for IBM.

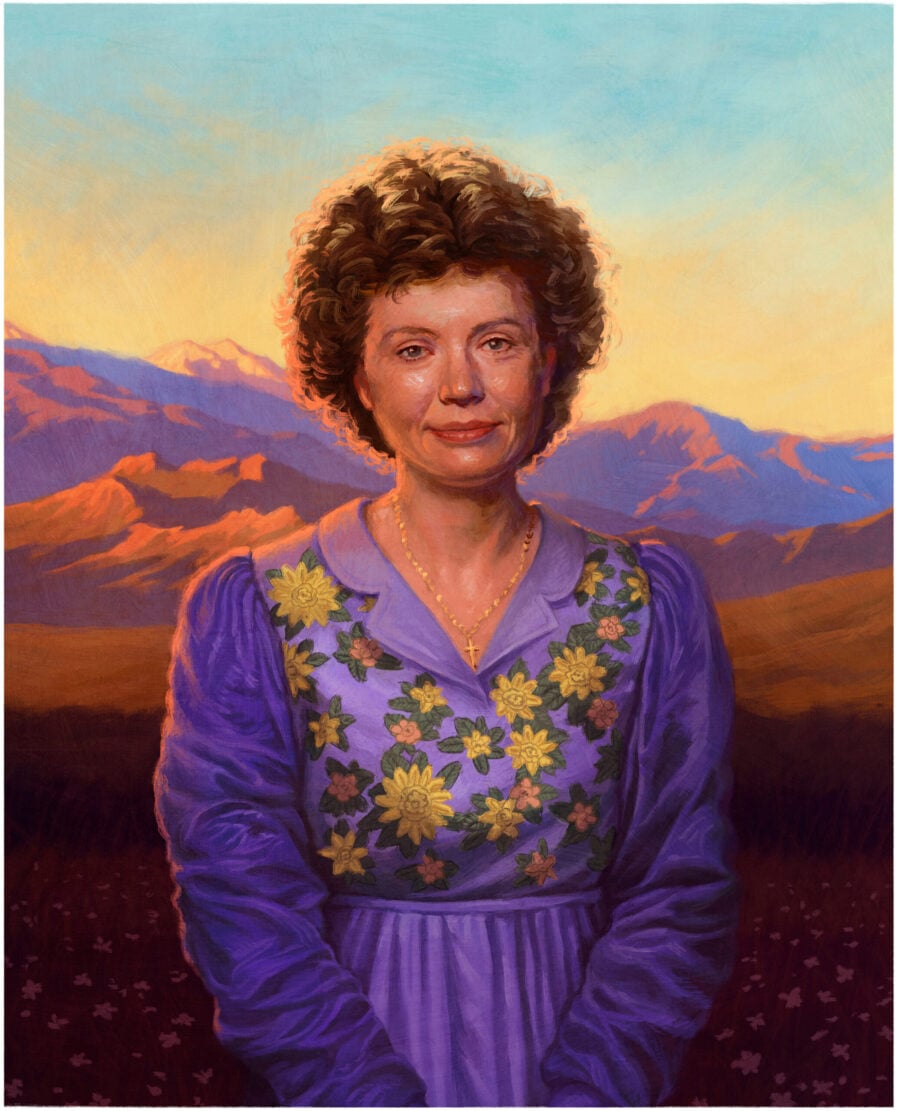

Elizabeth’s voice surrounds us. She addresses us not as the Messenger—the mouthpiece for Jesus, the Buddha, and her dead husband, each of whom inhabits her mind to transmit eternal truths—but as herself, as Elizabeth. She speaks about the growing epidemic of gun violence. She reflects on the biochemical and spiritual causes of depression. She doesn’t sound like Guinevere or a high priestess of Atlantis, as she claimed to be. She sounds like a PTA president. She looks like one too—like every bake-sale organizer, every field-trip chaperone, every dutiful mom I had ever seen outside girls’ dressing rooms at JCPenney on Sunday afternoons. Her makeup is neutral, tasteful, and perfect; her hair is short, brown, and permed. The trained eye can date her recordings by each iteration of that perm, reading the diameter of her curls like the rings of a tree trunk. By this method, and by an onscreen chyron, I determine that Elizabeth is speaking to us from the late Nineties. She sympathizes with our despair, but warns that it interferes with our ability to “hold the light.” We must be impervious to despair, she tells us.

“Are you impervious to despair?” she asks.

It was an interesting question to field from someone who spent at least $12 million preparing for Armageddon and, according to her daughter, considerable spiritual energy praying for it. In 1989 and 1990, under Elizabeth’s direction, the church constructed near the hills of Montana’s Paradise Valley and the gates of Yellowstone National Park what was at the time described as the largest private bomb shelter in the nation. There, on March 15, 1990, hundreds of followers waited for the nuclear strike that Elizabeth had prophesied in a series of increasingly impassioned public addresses over the course of several years. Over three days, they hunkered underground, surrounded by gold coins and assault rifles, only to emerge into the sunlight of a bitterly ordinary day.

I became fascinated with the church’s story, a Cold War reprise of the Great Disappointment of the nineteenth century, in which thousands of Millerites waited in vain for Jesus’ return on a Tuesday in October 1844. I researched the Church Universal on and off for years under the assumption that they were a historical footnote to a bygone era, only to discover that they were an active religious group that met on a weekly basis around the corner from my nail salon. (Though the church is headquartered in Montana, it maintains chapters, or “teaching centers,” all over the world.)

The longer I thought about it, this coincidence began to make a cruel kind of sense: church members had given everything to their belief that a surge of dark karma would swallow the world, but in fact the world had swallowed them whole and spit them out—in, for instance, Philadelphia, a karmic event if there ever was one. If anyone needed to remain impervious to despair, it was Eagles fans. And perhaps because I was a Philadelphian—bound in tribal solidarity with losers of all stripes—I felt sympathetic to the group: I couldn’t help but pity them for their great disappointment. Many of them had been coping with it for longer than I’d been alive.

I was born more than a year after members of the church went down into the shelters, and I turned thirty-two the day before I attended their services for the first time. Afterward, I had plans to eat birthday cake with my mom—like Pamela, I had grown up in the Philly suburbs. But I surprised myself by lingering for a few minutes and chatting. They sat around me on the plush purple carpet, listening to the facts I shared about my life with the warm curiosity I tended to associate with talk therapists and kindergarten teachers. When I finally told them I had to go—to celebrate my birthday, I explained—they burst into song. But the song was not what I expected. You are a child of the light, they warbled,

You were created in the image divine,

You are a child of infinity,

You dwell in the veils of time,

You are a daughter of the Most High!

I looked to Pamela, who looked back at me with perfect tenderness as she sang. Their voices were thin, wavering, sincere. Someone’s cracked a little on a high note. I couldn’t remember the last time strangers had sung to me for my birthday. Maybe once, against my will, at a Chili’s or something. I felt like I was five years old; I felt like the most important person on earth.

Elizabeth established the Church Universal in 1975, at a time when the nation was spawning new religious movements at a dizzying rate. While it would be fair to describe the church’s doctrine as New Age—Elizabeth herself used the term—it was also self-consciously rooted in nineteenth-century American esotericism: the church was only the most recent exponent of a set of teachings espoused by the Russian spiritualist Helena Blavatsky, who advanced the idea that all the world’s faiths amounted to a single body of knowledge authored by a pantheon of immortal beings. Guy and Edna Ballard, a husband and wife from Chicago, developed these beliefs in the Thirties in a series of books titled the “I AM” Discourses, and declared themselves Messengers for the Masters on earth. When Elizabeth met Mark in 1961, he was leading a Ballard offshoot group in the D.C. area and had proclaimed himself Messenger; Elizabeth was a twenty-two-year-old secretary at the Christian Science Monitor, unhappily married to a Christian Scientist and eager to find solace in a community of fellow Ballard devotees. Shortly after their meeting, Mark informed her that the Masters had disclosed to him their desire for her to be his “spiritual partner.” Elizabeth accepted his proposal, leaving her husband and assuming the office of Messenger by his side.

After his death by stroke in 1973, Mark became known as Ascended Master Lanello—a portmanteau of Lancelot and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, each of whom he had claimed as previous embodiments. Elizabeth remained the sole Messenger on earth until her death from Alzheimer’s in 2009. The church has yet to name a successor. The thousands of hours of recordings that the church maintains—stacked alongside nonperishable food in its bomb shelters—has allowed her to attain a practical immortality even with her most recent embodiment in the grave. Besides, it’s hard to know who would replace her.

In 2021, General Michael Flynn, the Christian nationalist and former national security adviser to Donald Trump, gave an address at a nondenominational church in Nebraska that internet sleuths suspected had been plagiarized from one of Elizabeth’s “dictations,” as her dispatches from the Masters were known. One helpful YouTuber spliced together footage of the two for comparison. Both propose a religious call to arms and entreat the “freeborn” to resist becoming “enslaved by any foe,” while making confusing allusions to “sevenfold rays” and “legions.” But Flynn recited this prophetic word salad with the delivery of one’s least-favorite uncle plodding through an ill-prepared wedding toast. Elizabeth—with her precise elocution, her terrifying and obvious sincerity—sounded like a woman on the brink of a great cosmic battle.

QAnon conspiracy theorists, who quickly noted that some of Flynn’s language wasn’t exactly biblical in origin, believed the “occult prayer” exposed Flynn as a satanist. But if the incident reveals anything besides the mutinous humor of Flynn’s ghostwriter, it’s the degree to which millenarian rhetoric has saturated American public life. In 1960, the sociologist Daniel Bell predicted “an end to chiliastic hopes, to millenarianism, to apocalyptic thinking—and to ideology.” But as the historian Paul Boyer has noted, after the great revolutionary movements of the Sixties waned in America, much the opposite came to pass. Prophetic belief—whose adherents, in Boyer’s description, “take very seriously the Bible’s apocalyptic sections and derive from them a detailed agenda of coming events”—exploded in popularity during the Seventies and Eighties. Such beliefs have shaped not only American religiosity but our understanding of the human psyche itself.

In the Fifties, the psychologist Leon Festinger coined the Psych 101 term cognitive dissonance, based in part on research he’d done for the book When Prophecy Fails, which described the mental state of a Fifties UFO cult after its leader’s apocalyptic predictions went unrealized. There have been so many of these groups, flourishing and flaming out in endless cycles, trading places in a Beckettian limbo wherein divine reckoning approaches but never arrives. They have furnished streaming services with an endless supply of podcasts and documentaries rehearsing the history of America’s ill-fated apocalyptic sects and outsider religions. But whenever I try to place Elizabeth in this tradition, I come up short. She would be easier to categorize had she been more like Jim Jones, to whom she was often compared, or Charles Manson, whose Family had allegedly sent her death threats. But while her church was armed to the hilt, they never killed anyone; although Elizabeth could be mercurial and vindictive, she was a beloved mother of five. Were it not for her prophecies of nuclear Armageddon, it’s possible that the church would have remained one of the many fledgling religions eking out its existence far from the center of American life. Perhaps the one thing Elizabeth had in common with the believers of those other faiths was that she, like so many Americans before her, could imagine no greater spiritual fulfillment for herself or the nation than an extinction event.

I wanted to go to Montana, where Elizabeth’s prophecies drove her followers underground. There, I thought, I might understand the persistence of prophetic belief in American life, which seemed to proliferate even as rates of mainstream religious affiliation waned. At the very least, I wanted to better comprehend how the church had lasted so long. Many left soon after the shelter episode, but a perplexing number remained. The failure of Elizabeth’s prophecies was itself a disaster of apocalyptic scale—a shattering irony that threatened to transform the remainder of their lives into mere epilogue. And yet their fate was in some ways enviable. I first read about Elizabeth in the winter of 2020–21, a time when, for obvious reasons, it was easier to sympathize with a people who had engineered their downfall by overpreparing for catastrophe. At the time, it was comforting to imagine the believers on the worst day of their lives, emerging from their concrete bunker only to discover that the world they left behind was still there, indifferent and untroubled. Their great disappointment seemed to me a kind of miracle: what a relief to imagine a future in which the worst thing that could happen was that the world didn’t end. While I wondered if I would drink in a dive bar or dance at a concert or hug my mother ever again, it was soothing to imagine that I too would one day leave my isolation and find the world exactly as I’d left it.

Although I envied Elizabeth’s followers for the paradise they regained, I also pitied them for the same reasons I pitied myself. While a droll acknowledgment that the world was ending had become obligatory among my peer group—white, millennial, middle class—there was little about our behavior to suggest that we actually believed it. We said it was pointless to save for retirement, but we saved for retirement. We said we couldn’t imagine bringing children into this world, and then we brought children into the world. Perhaps we were indifferent; perhaps we were in denial. But I also wondered if we were soothed into passivity by a vestigial belief deep in the collective psyche that someone was coming to save us. I suspected that this was true for me, and that my tenderness for them sprung from this truth. The debunking of their beliefs confirmed their existential loneliness, which was also mine. I couldn’t muster any smug satisfaction at the failure of their prophecies, not so long as I suspected the reason for their terrible prayers going unanswered was that there was no one there to listen—not to them, not to me, not to anyone.

The ranch, as the church’s headquarters are known, is located in Corwin Springs, Montana, an unincorporated community about eight miles from the northern entrance to Yellowstone National Park. You can see the church as you approach from Gardiner, the tourist town where I stayed. I did not notice a sign announcing its presence to passsersby, and save for the small white crosses marking traffic fatalities, there’s hardly anything to interrupt the majesty of the road as it curves through the red mountains of the Gallatin Range. This land, according to church doctrine, is among the most sacred places on earth, but to the nonbeliever, it looks just like any other string of dusty ranches and sporadic campgrounds—beautiful, lonely, and largely unchanged since the closing of the Western frontier. Bison mosey on either side of the road, swinging their dainty tails. Elk curl up on the ground like big cats. But when the sun is strong, you can glimpse something glinting in the hills: the top of the church’s gold-toned steeple catching the light like a capped tooth. Following that flash, I turned left onto a narrow metal bridge and crossed a looping turquoise stretch of the Yellowstone River. On the other side, beside a dirt road, a small wooden sign pointed the way to the Royal Teton Ranch.

The church purchased the property, then 12,500 acres, from the Forbes family in 1981. After Mark’s death, Elizabeth informed her followers that the move to Montana had been among his final instructions. Legal trouble had already cast a pall over their previous home, in southern California, where the group had lived in a sprawling gilded mansion they called Camelot. Elizabeth insisted that California was polluted by bad karma; the ranch, by contrast, was free of karmic and other pollutants, a mountain paradise appropriately located on the edge of Montana’s Paradise Valley. The organization later parted with much of its property, the ranch having contracted to some 7,500 acres that included sites like the church, called King Arthur’s Court, and a remote mountain valley they called the Heart of the Inner Retreat, accessible by a long, unpaved road that climbs a thousand feet in elevation. The Heart, considered the most beautiful place on the property, is where Elizabeth brought students from the spiritual classes she called Summit University. Photographs show her standing in the long grass framed by a backdrop of green hills, her followers seated in a circle at her feet. It is also where they built their bomb shelter.

I had come to the ranch for the largest of its quarterly conferences, this one marking the Fourth of July, a holiday with special importance in their doctrine. The conference involved several days of services for veteran members, as well as a sort of spiritual onboarding program called Essentials, in which I had enrolled, scheduled to take place in King Arthur’s Court. Despite its title, the Court was a beige, bland, modern construction with all the Arthurian grandeur of a McMansion.

I had come to the ranch for the largest of its quarterly conferences, this one marking the Fourth of July, a holiday with special importance in their doctrine. The conference involved several days of services for veteran members, as well as a sort of spiritual onboarding program called Essentials, in which I had enrolled, scheduled to take place in King Arthur’s Court. Despite its title, the Court was a beige, bland, modern construction with all the Arthurian grandeur of a McMansion.

Inside, I followed signs for the Essentials track to a small, windowless chapel with an altar and a giant framed portrait of the turbaned and bearded El Morya, the Ascended Master that Elizabeth claimed as her spiritual guide. The artist, in the typical Summit Lighthouse style, rendered him with the oversize, wet-looking eyes of a Disney princess. I took my seat along with twenty or so other “newbies,” as one woman referred to herself. We were sequestered from the majority of the in-person attendees in the main chapel, where the more advanced work, I later learned, took place.

Guiding the newbies were two beatific white-haired women, Paula and Carla, who greeted us and the hundreds of people attending via Zoom. After the briefest of overviews of the church’s history—most conference attendees weren’t exactly neophytes—we watched an opening invocation by Elizabeth, in which she called on the divine to protect America’s youth from “malevolent and discarnate spirits.” Then we watched what I can only describe as a confusingly erotic biblical cartoon: a two-and-a-half-minute video in which John the Apostle—long-haired, shirtless, needlessly ripped—zips through space and time, summoning a New Jerusalem out of the mountain landscape of the American West. A booming voice-over quotes the Book of Revelation while a faint choir harmonizes ecstatically in the background. The Essentials program, Carla explained, would “take us from where we are right now in consciousness into a new heaven and a new earth.” No one had mentioned the bomb shelter yet.

“A New Heaven and a New Earth” was the theme of this year’s conference, which marked the thirty-third anniversary of the so-called shelter cycle, when Elizabeth’s prophecies culminated in the three nights underground. The catalyst for her doomsayer turn is unclear, but her daughter Erin speculates that the prophecies were incited by troubles that she had endured in the Eighties; some believe this was the actual reason for the church’s move to Montana. In 1981, the church sued Gregory Mull, a former member, over a $32,000 loan he had failed to pay back; Mull filed a $253 million countersuit, claiming that the money had been a gift and that he had been a victim of “coercive persuasion” at the hands of Elizabeth and her church.

Central to the Mull controversy—and to the church’s teachings—was something called a “decree,” a form of rapid, accelerating prayer performed at the pitch and speed of an auctioneer’s prattle. You can hear it on The Sounds of American Doomsday Cults Vol. 14, an obscure album that circulated for years in avant-garde music circles. As far as anyone knows, the other thirteen volumes don’t exist. The label that released it, Faithways International, has issued only one other recording: a collection of songs by the leader of the Japanese terrorist cult Aum Shinrikyo. Vol. 14 consists of a continuous recording of one of Elizabeth’s services, likely from the Eighties, in which she rails against the “misuse of the four-four time” and prays for those subverted “by the syncopated rhythm of the fallen ones.” Highlights of the recording are a roll call of some seventy names of presumed fallen ones—everyone from Michael Jackson to Def Leppard—and the eerie, unsettling sound of the decrees. The church’s critics described it as “Satan’s hum.” Mull and his lawyers described it as hypnosis. To me, it sounded like spoken-word poetry as performed by a hive of bees.

That night, Patricia, a handsome black woman in a sparkling purple sweater, guided us through our first decree session. Each of us, she explained, was a “spirit spark’’ who had become “trapped in a physical body.” By doing our decrees, we could begin a process of reunification with the divine. “We’re gonna make it a singsongy voice, and then do it faster,” Paula said delightedly, directing us as though we were actors in a school play. Over and over, we repeated: “I am a being of violet fire, I am the purity God desires!” The newbies beside me did their decrees with cheery, practiced ease; as we gained speed, I stumbled over the words, my tongue twisted. By the final repetition, the decree had morphed into something spooky and Seussian, something in between incantation and nursery rhyme.

It was on July 4, 1988, that Elizabeth stood before an enormous American flag and delivered one of the prophecies that would drive her followers underground. Wearing a white coat, she spoke for six hours while the Montana sky darkened from day to night above her. In a nearby RV, her pregnant daughter, Erin, watched the address on a video monitor and thought: “Something seemed seriously wrong with Mother’s sense of time.”

In truth, something had been wrong with Elizabeth’s sense of time since childhood. Born in 1939 in Red Bank, New Jersey, Elizabeth was the only child of a German immigrant, Hans Wulf, and his Swiss wife, Fridy. In a school photo, Elizabeth looks like an aspiring Donna Reed, with poodle-curled hair and dainty white gloves. At home, her life was sometimes chaotic and unpredictable. When she was not yet three, her father was detained on suspicion of espionage, an experience that darkened her youth. Within a few years, she had grown accustomed to strange lapses in her head: sudden, fleeting moments of mental absence that frightened and confused her. These “blackouts,” she suspected—later diagnosed as petit mal seizures—were her means of escaping her father’s drunken rages. In grade school, a teacher had roused her from an episode by grabbing her shoulders, screaming in her face, and promising to “shake the devil out of” her. Though she wasn’t raised in any formal religion, she noticed the convictions of the religious people around her.

Fridy, in her own way, helped to shape the evolution of her daughter’s beliefs. Shortly before her death, she confessed that she had tried to give herself an abortion while Elizabeth was in the womb. She had never forgiven herself for it, nor did her daughter. The latter remained convinced that the drug her mother had ingested to abort her still lingered in her brain and body, a belief that shaped her vehement pro-life politics as well as her diet, which included frequent health cleanses in the hope of purging the poison from her system. In addresses, she inveighed against sugar, alcohol, and junk food. Notoriously, the church discouraged expectant mothers from consuming chocolate. Her followers were encouraged to be vegetarians and eat most of their meals in the ranch’s cafeteria, away from the evils of added sugar.

So I am not being glib when I say it is difficult to imagine these people drinking Kool-Aid under any circumstances. In between sessions in El Morya’s chapel, I walked down to the dining hall in one of the handful of prefab buildings that housed some of the attendees who had traveled to the conference. The church depended on paid staff for most of its daily operations, but participants would receive a free lunch in exchange for volunteering for something like meal prep. Or so I had been told by Jennifer, a thirtysomething newbie who took furious notes during the Essentials sessions and responded to my salvos of small talk with the muted interest of someone who had not traveled to Montana to make friends. In the cafeteria, I spotted her wearing an apron and manning a food station along with Carol from the Philadelphia chapter, who wrapped me in a hug and greeted me with peals of delight as though we had known each other for years.

As Carol drifted away, summoned by cheerful cries of recognition, I considered my food options. Most of them were viscous. There was a carrot stew, a trough of gooey black beans. Beverage choices included “reverse-osmosis water.” I cringed, but then felt a stab of contrition. My meals, for the past several days, had consisted of twenty-dollar burgers from a place called the Corral and freezer-burned pizza from a casino bar where I spent my evenings feeding dollar bills into slot machines and drinking complimentary beer. It would not kill me, I told myself, to eat something healthy.

I bought dinner from the cafeteria and sat down at a long square table, picking at the edges of my meal. The room gradually filled. I was joined by Anna, Elizabeth, and Kirsten, a fiftysomething brunette with dramatic eye shadow and little strands of iridescent tinsel threaded throughout her hair, as well as Kirsten’s husband, Marcus, who works in IT. Anna, freckled and British, peered at Kirsten and then back at me, her eyes darting theatrically. “The two of you have the same eyes!” she exclaimed. Kirsten shot me the briefest of glances over her meal. “You must be from the same soul group,” someone said mildly.

The table got to talking. I asked the women how they came to the church. Kirsten explained that her mother had introduced her when she was seventeen, then informed me that three generations of her family—her mother, her children, and she and Marcus—were in attendance at the conference. Anna said something confusing about angels and an ex-boyfriend, her prim British voice barely audible over the clamor of the cafeteria. Elizabeth, an older lady with white hair and fuchsia cat-eye glasses, explained that she had always been a “searcher” and heard about the Prophets from a woman she met at work. She saw the truth of their teachings at the first service she attended, when an angel sat beside her.

“How did you know he was there?” I asked.

“I saw him!” she said. “With my third eye,” she clarified. “He was big!”

Soon, the women paired off into their own conversations. Marcus, who had endured our chitchat with the polite boredom of husbands at social functions everywhere, rose with palpable relief to go talk to someone he knew. Alone at the table with Kirsten, I regarded her more clearly; aside from the tinsel in her hair, she appeared less ethereal than I’d first thought. She was buxom and forthright, with something subtly appraising in her manner, and though she had finished eating, she lingered at the table, evidently in the mood to talk. “So what do you believe?” she asked me. “Past lives, anything like that?”

“I wish,” I said. After my father died, I explained, I tried to imagine that he had returned in various forms—a colorful bird, an interesting cloud—but the efforts always felt strained and intrusive, like I was goading a dead guy into playing charades. Kirsten frowned in sympathy. Before she could respond, two lanky blond teenagers, a boy and a girl, galloped up to our table and asked her permission to go to the hot springs next door. They were beautiful kids, sunburned and giddy. There were altogether more children and young people at the conference than I had envisioned. Elizabeth Prophet’s own, now mostly middle-aged, were conspicuously absent. Elizabeth had expected her two eldest, Sean and Erin, to be her most faithful chelas, a term derived from Sanskrit that could mean either “disciple” or “slave” depending on whom you asked. The rest of the chelas were of varied backgrounds and vocations: they were engineers and psychiatrists, architects and lawyers, and in one case, a vice president of Chase Bank. They even once included, as Erin writes in her memoir, Prophet’s Daughter, “a real live rock star”: Ron Strykert, of the Eighties band Men at Work. Overwhelmingly, they were college-educated. Many of them had been raised Catholic. Kirsten told me that, though her husband voted Democratic, most of the church’s members were “constitutional conservatives.” (This wasn’t exactly news to me. Every altar had an American flag on it; Elizabeth habitually inveighed against the evils of Communism in her dictations and lectures. At the back of the main chapel stood an enormous, framed copy of the Constitution.)

Here I was, in the West, eating my vegetables in a church cafeteria with staunch anticommunists in the middle of a mountain range, a tableau that could have scarcely seemed more patriotic if a bald eagle had alighted on my shoulder. It was the Fourth of July, after all, and I was dining with people who had come together to celebrate their love of God, country, and their moms. My own mother was a schoolteacher who lived in Pennsylvania and collected ceramic cups with horses on them; theirs was a woman who had stridden about her Montana ranch in the company of armed men whom she called her Cosmic Honor Guard. Through her prophecies, Elizabeth imbued her lifelong otherness with a higher purpose, carving out a place for herself in the nation’s destiny. As a Prophet, she ceased to be Betty Wulf, daughter of a suspected German traitor, and became, unquestionably, a true American. Her church is a tribute to that transformation.

The winter of 1989–90, Daniel Kehoe recalled, “had to be one of the coldest, snowiest winters we ever had.” Folksy and earnest, he spoke of his time preparing for the apocalypse with a mix of pride and chagrin, like someone remembering a particularly foolhardy kitchen renovation. Along with Paula, Carla, and a man named Steven, Daniel was addressing the newbies in person and via Zoom for a “roundtable discussion.” It was the first time that I had heard any of them acknowledge the shelter episode explicitly—what they call the shelter cycle, or the shelter drills—and I was surprised by how merrily they spoke of it. “We went through tests day and night,” Daniel said wryly. Such is how the believers interpret the events of that year, in which they moved their entire lives belowground: as a test.

That year, under Elizabeth’s direction, the church’s men and women began around-the-clock work on an excavation site larger than six football fields. Daniel, who had professional experience overseeing large construction projects, supported the efforts to build a parallel complex of shelters in nearby Glastonbury. The ranch’s complex was intended to house around 750 people, many of whom had been living at the church. Made of steel and concrete, the structure consisted of multiple underground passages arranged in the shape of an H and divided with submarine-style doors. The largest of its shelters was big enough to fit a semitruck. Each was equipped with decontamination chambers at its entrance—shower stalls, landlines within reach—to wash off radioactive fallout. The church built bunk beds with purple seat belts on them. There were infirmaries and laundry facilities. Radiation suits and Geiger counters and body bags. Huge armored trucks designed for transporting military combat crews. They had enough food to last them seven years—floor-to-ceiling grain supplies, nonperishables. According to Erin, they had a tractor trailer’s worth of Isuzu pickup trucks. Beneath the bunker, in a chamber, they had more than five million dollars’ worth of gold and silver bullion, as well as twenty-five thousand dollars in pennies. (Paper currency, they suspected, would have little use in the postapocalyptic world.) And they had guns: fifty AR-15s and thousands upon thousands of rounds of ammunition, for defense against roving bands of marauders.

All told, the church spent around $12 million on the project. Members quit their jobs, emptied their bank accounts, sold their furniture, their cars, their houses. Those who couldn’t afford the move to Montana or fees for the smaller, privately built shelters nearby took out pleading ads in the paper: “Urgent mother with three small children needs loan for shelter space,” read one. Others advertised space in their own DIY shelters, made from buried oil drums or prefab bunkers, for as much as $4,000.

On March 14, 1990, Elizabeth’s followers went underground, where they were prepared to remain for a period of possibly seven years. They brought their suitcases, their children, their handguns. In her memoir, Erin recalls a certain ambient giddiness at the nearness of the golden age, at the sure vindication of their beliefs. The church’s guards patrolled the ranch’s perimeter. Elizabeth, her neck layered in jewels, her fingers covered in rings, decreed deep into the night. There were rumors that agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives watched from the hills.

“ ‘Well, we built them and nothing happened!’ some people were thinking,” Carla recalled of the morning that followed. Noah faced the same difficulties when he built the ark. People laughed at him, too. But something did happen that day, according to Steven: they saved the world. Back then, he explained, the jolliness in his tone giving way to a thundering self-seriousness, “we were in—thirty-three years ago—the middle of what we now know as the Cold War.” And by making “the effort to survive and preserve the teachings,” they kept the Cold War from becoming a hot war. Their preparations called forth a “divine intervention” that stopped the missiles from falling.

Crazy, perhaps, but not much crazier than America’s own approach to nuclear preparedness: What is “deterrence,” after all, if not the belief that preparing for disaster is tantamount to preventing it? The believers’ commitment to surviving a civilization-destroying cataclysm struck me as grim (who would actually want to inherit such a devastated world?), but it was one they shared with defense intellectuals shaping America’s nuclear policy for much of the Cold War. In 1992, two years after the church completed construction of its shelter, the Washington Post revealed the existence of Project Greek Island, the code name for the secret congressional bunker that the government had been maintaining under the Greenbrier resort in West Virginia since 1957. The bunker, meant to ensure the continuity of government in the event of a nuclear strike, made no accommodations for the rest of the nation, who would be left to duck and cover.

But preparation for disaster can often suggest a sublimated desire for it. And what no one on the Essentials panel acknowledged, as they summoned the events of 1990, was how furiously some prayed for the nuclear holocaust the group now credits itself with preventing. As Erin writes in her memoir, by the second night underground, the mood among the group had changed from jubilation to tense, muted desperation. Elizabeth gathered her closest followers and told them it was time to call down judgment upon America. Together, they swung their ceremonial swords and called on Jesus Christ to punish “the evils continuing in the earth.” Elizabeth, wielding her own sword engraved with the name archangel michael, called on its namesake to “let the bombs descend.” Erin, along with many of the others, would mark that day as the beginning of the end of their involvement with the church.

If the bombs had fallen, they would have confirmed Elizabeth’s clairvoyance; they would have smitten her enemies; they would have installed her at the helm of a golden age. But prophetic beliefs can be easily rigged to elude disconfirmation. The person who predicts an 80 percent chance of rain can point to a cloudless sky and remind critics that he had also allowed for a 20 percent chance of sunshine. The sect that hangs its hopes on a specific Day of Judgment can always claim after the fact that it prevented the very apocalypse it had predicted. Either way, faith is affirmed. Through such rationalizations, the believer ensures that no matter what happens—no matter what she wants to happen—she’ll find herself on the right side of prophecy.

This modification of belief, I thought, was perhaps how Elizabeth’s followers remained, as she had once put it, “impervious to despair.” But as I drove back to my Airbnb, I recalled the desperation that had resulted in my own journey to Montana: the months I had spent in the depths of the pandemic rewatching the Lord of the Rings movies, researching Elizabeth, and rereading Kierkegaard, the most anguished of the Christian philosophers. When the pandemic subsided, I stopped reading books with titles like Fear and Trembling and started doing other things, like taking showers. But now I pulled up a PDF of The Sickness unto Death on my phone for old times’ sake. The “despair at not willing to be oneself,” Kierkegaard writes, is an unconscious despair, a disease of the spirit. Fleeing the demands of selfhood, one spends his life with his “face inverted,” refusing to confront the despair that is “going on behind him,” trailing him like a shadow. I was struck by this image; it reminded me of Elizabeth, who sometimes began her dictations with her ringed hands raised and her back turned, waiting for the Masters to speak through her, to transform her into someone other than herself.

Yellowstone Hot Springs, its website boasted, is “a soaking experience unique in the world.” The lobby, when I arrived, was plain and touristy, with wood-paneled walls and displays selling T-shirts, mugs, and national park memorabilia. Though the church once had grand ambitions for these waters—Elizabeth had dreamed of channeling them into the ranch to heat its greenhouses—the only evidence of the church’s involvement was a small shelf of Elizabeth’s books by the entrance, which I inspected as I paid for my ticket. The woman at the register was mild-mannered and blue-eyed—a member of my soul group, perhaps.

“Are you affiliated with the church?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said proudly. “Are you a Keeper?”

I nodded, recognizing her reference to the Keepers of the Flame, a fraternity within the movement.

“I charged you too much, then,” she said reflexively, and handed me a one-day pass.

It was the golden hour. The pools were full of park visitors, tanned and tired and happy, crusty with the outdoors. I waited for a spot to open up in the hottest pool and clambered in, settling into the water with an amphibious calm. As I watched my legs turn pink, I felt a rosy glow of fellow feeling for everyone stewing beside me. The other attendees had prodded me all weekend to visit the hot springs, but if they were here among us, I couldn’t tell. I spotted a mother and daughter with parts down the center of their hair and long-sleeved bathing suits: possibly Keepers, possibly Mormons, possibly just modest. I turned to a guy with a nose ring and the sweet, sun-chapped face of a young Robin Williams, and asked him if he had heard about the church next door.

“I have not,” he said tersely. I realized that I sounded like a proselytizer.

“Just wondering,” I said, embarrassed. “I hear that they’re a cult or something.”

Perhaps Elizabeth’s delusions were a symptom of her illness; perhaps they were a tragic consequence of hubris. But that hubris was hardly unique to her, given how secular modes of prophecy have come to predominate in everyday life. In Seeing into the Future, the historian Martin van Creveld chronicles the history of forecasting, tracing the way that speculation evolved, over the course of centuries, from an occult religious practice to Cold War statecraft and a critical part of the world economy. Once the province of mystics and mages, prophecy has now become the purview of think tanks, meteorologists, and market analysts. But people today, van Creveld points out, are hardly better at predicting the future than their superstitious predecessors. Elizabeth’s life is a reminder of the awful irony that in the nuclear era, technical knowledge has given human beings the power to destroy their future without allowing them to reliably predict it.

Today, church members seem to have given up on prophecy, if not their prophet; they have turned away from the uncertain future toward the certainties of their past, when their Mother was still lucid, still alive, still looped on video. Though they have never acknowledged her death—they speak exclusively of her “ascension”—they have been mourning her unceasingly since the day she died: October 15, 2009. Maybe this is what it meant to be a child of infinity: you grieve your parents infinitely. To do so is, perhaps, a practice akin to faith. The love of a parent was the closest I had come to knowing the love of God. If I could believe in one, it seemed possible that one day I could believe in the other. I was moved by Kierkegaard’s notion, as I understood it, that you could live your life within arm’s reach of grace but with your face averted—that you could be both estranged from God and close to him.

On the Fourth of July, I headed to King Arthur’s Court for the climax of the conference. Characteristically, the church was not celebrating the Fourth with beer or barbecue but with a waltz. After the services, I lingered to watch the Court transform into a dance floor. (According to the believers, the Ascended Master St. Germain inspired Strauss’s waltzes, whose 3/4 rhythm mimics the beating of our hearts.) Women of all ages gathered in flowing dresses of teal or pink or lavender, and hung garlands of flowers. Others laid out plates of cheese and rows of seltzer. Mostly, they spun, singly or in pairs, waiting for the music to begin. I studied two young women giggling and fussing with each other’s hair: both beautiful, both blond, both pregnant. A crisply tanned woman with chunky highlights twirled with her teenage son, who then passed her off to his father, a man I recognized from the Essentials crew by his gold chain and overpowering cologne. One middle-aged woman in a dusty-rose dress stood away from the crowd, spinning round and round in solemn concentration as though performing some private spell.

As I watched, I thought of Elizabeth, who had also loved to dance and who, several years after the shelter cycle, according to Erin, apologized to her children. She had abused her power in her ministry of the church, she said. But by then it was too late. A few years later, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. She would never be quite so lucid again. Erin remembers that admission with a pained optimism for what might have been. She sees in that moment of brief, belated moral clarity the possibility of a different outcome—of a fuller reckoning with the harm Elizabeth did, of the mistakes she made—had she remained healthy. Perhaps nothing is an expression of greater faith in her mother than this rejection of the fatalism that defined her. As “The Blue Danube” was piped in over the speakers, I held my fingers to my wrist and tried to count the tempo of my heart: not quite a waltz, not quite a march, but something both more and less than music—the steady measure of ordinary time.