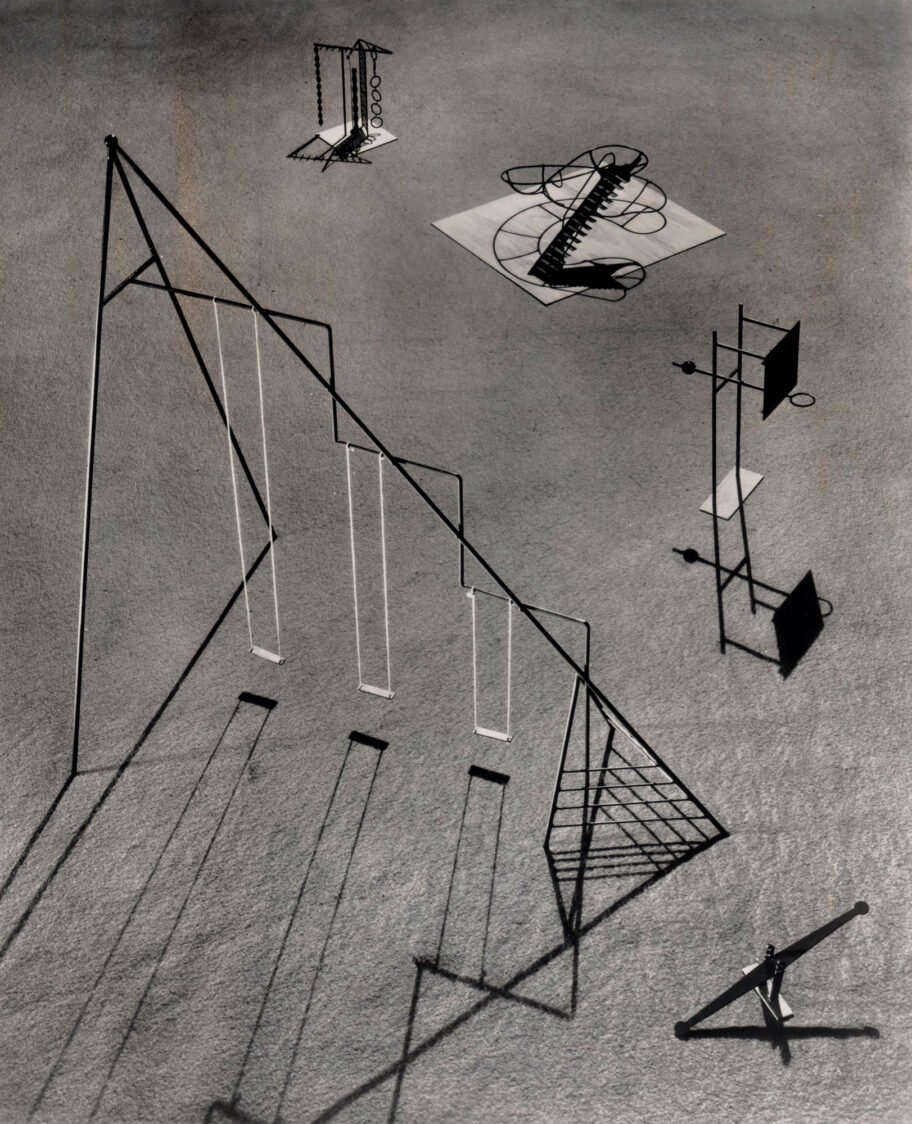

Jongensland, an experimental play area in Amsterdam, 1969. Photograph by Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, from her book Huts, Temples, Castles. Courtesy the artist and MACK

There’s a chapter in Mrs. Bridge, Evan S. Connell’s novel of country-club claustrophobia, in which the Bridges’ young son, Douglas, erects a “tower of rubbish” in a vacant lot near their home in Kansas City. The tower comprises brass curtain rods, a bent skillet, old golf clubs, cereal-box tops, and miscellaneous refuse from the neighborhood, held together by concrete and the boy’s unwavering pluck. Eventually, it stands more than six feet high, an “eccentric and mystifying memorial” that begins to attract visitors. Mrs. Bridge, the picture of Midwestern reserve, is “troubled by its solidity,” and also by the fact that Douglas, when questioned about his activities, says that he’s “just playing.” A man at a cocktail party tells her that it’s “a curious form of protest”: “ ‘You are aware of the boy’s motivation, are you not?’ To which she smiled politely, being somewhat confused, and made a mental note that the man had been drinking.” She phones the fire department the next morning, and two firemen spend the better part of a day demolishing Douglas’s naïve masterpiece. “It was just getting too big,” she confides to her son. “People were beginning to wonder.”

Play can upset the order of things. It has a hidden force. There aren’t enough firemen in the world to dismantle the sick dreams of every Douglas, but would it be asking too much of adults to encourage his rebellion? For a time, cities in Europe and North America provided places where children could “dare to be destructive and thereby constructive,” as one playground supervisor saw it. Ben Highmore’s Playgrounds: The Experimental Years (Reaktion Books, $35), which lives up to the handsome simplicity of its title, tells of Emdrup, a Danish “junk playground” (Skrammellegeplads) designed in 1943 by Carl Theodor Sørensen, a landscape architect who’d envisioned a plot rife with

all sorts of old scrap that the children from the apartment blocks could be allowed to work with. . . . Branches and waste from tree polling and bushes, old cardboard boxes, planks and boards, “dead” cars, old tyres and lots of other things, which would be a joy for healthy boys to use for something. Of course it would look terrible . . .

It did look terrible: a gash of dirt in working-class Copenhagen infected with an ever-mutating, kiddie-size shantytown. What fun, though. Children found that the place gave them free rein to express parts of themselves they never had before. Like Douglas, they wanted a tower, and after extensive consultation they built a behemoth of over fifty feet capped with a wind turbine that apparently powered the playground’s lights. It, too, was destroyed, supposedly because kids kept falling from it, though it may only have been that grown-ups found it supremely unsightly. “Of all the things I have helped realize,” Sørensen wrote, “the junk playground is the ugliest: yet for me it is the best and most beautiful of my works.”

Emdrup marked a new phase in “the playground movement,” which had flourished across Europe and North America since its origins in the “sand gardens” of nineteenth-century Berlin. In 1898, Joseph Lee, a wealthy Bostonian and vocal opponent of immigration, helped open a model playground in the hopes of assimilating his city’s ethnic enclaves. To Lee and his fellows in the Playground Association of America, city children required not mere distraction but rescue: from delinquency, capitalism, fascism, or just from frittering away their time in cemeteries or down by the railroad tracks. “We may either smother the divine fire of youth,” wrote one advocate in 1909, “or we may tend it into a lambent flame.”

The first playgrounds in the United States had a martial quality, catalyzing “the expression of mass feeling” by allowing for military-style drills and dancing, sometimes with a gramophone on a trolley nearby. (An early 1920s advertisement, “The Victrola in Mimetic Play,” suggested adding “the joy of music to your informal gymnastics.”) Kids could spend all day at such places; they were always supervised, and if the weather turned, indoor facilities accommodated reading, basket weaving, and carpentry. The ambition was an unpolished collectivism. Conventional equipment like swing sets and jungle gyms served to induct children into civic life by strengthening them for the body politic, whereas uninviting premises would shunt them toward crime or prostitution—there was, seemingly, no middle ground. “The boy without a playground,” said Lee, “is the man without a job.”

Junk playgrounds like Emdrup came decades later. They were soon rebranded, understandably, as “adventure playgrounds,” where pickaxes and wheelbarrows were supplemented with softer diversions. By 1980, adventure playgrounds in the United Kingdom numbered in the hundreds; many were integrated into bomb sites from the Blitz. Kids tinkered amid the blights and craters of war. They sat at grand pianos, built forts, published magazines, and cooked over campfires. By popular vote, the children of London’s Lollard Adventure Playground decided to mend clothes and chop firewood for pensioners. They learned an elevated form of sharing, something like resource allocation.

“Sculpture by Isamu Noguchi, 1933–1941,” a photograph by Fay S. Lincoln of Playground Equipment for Ala Moana Park, Hawaii, by Isamu Noguchi © 2024 The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum (INFGM/J110P111), New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Penn State University Libraries. Used with permission of the Eberly Family Special Collections Library (01628)

I waited for Highmore to compare their makeshift civilization to an inverted Lord of the Flies. He does, writing that “it is against such an image of crypto-fascist naturalism that the junk playground offers another image of cooperation and spontaneous democracy.” Then again, the boys in Flies were never under watch. The adults charged with monitoring experimental playgrounds were uncertain of how to cast themselves, favoring terms like “warden” or “playleader” before settling on my personal favorite, the oxymoronic “playworker.” Their immersion left them with a dilating sense of time and sophisticated theories of kinder-ecology. In their work logs and diaries, they testify to a constant negotiation of boundaries—the simulation of secrecy, the refusal of pedagogy. “I cannot, and indeed will not, teach the children anything,” wrote one. Another was said to be “diffident with the prim little girls, as large men always are,” while a third reported that “a gang of boys inside the compound asked me to go away because they felt ‘daft’ if I watched them playing pirates.” Playworkers tried to accommodate everyone without judgment, including, at Lollard, a twenty-two-year-old habitué who “adds a corpse or two to an architectural painting or ‘plays’ for a while with a noose thrown over a beam.”

Where does someone like that play now? The metaverse would boot him out for violating the terms of service. You can guess how experimental playgrounds fell out of favor. It’s the likes of Reagan and Thatcher scissoring through the social safety net. It’s high-handed Robert Moses, who, in 1934, rejected “Play Mountain,” a utopian design by Isamu Noguchi for an undulant, unadorned pyramid of earth in Central Park. “Moses just laughed his head off and threw us out,” Noguchi remembered. Playgrounds ossified, in the words of one New Yorker, into “the banal swing set. The bone-jarring seesaw. The galvanized slide. The joyless sprinkler.” Highmore has found another way to describe the grueling close of the twentieth century: as a thoughtless circumscription of the places, and therefore the reasons, for play, as “our imaginations have been colonized by a specific cultural form.” He takes playgrounds very seriously—academically, yes, but with the passion of one who’s been too long at the monkey bars. “A book looking at playgrounds in the Global South needs to be written,” he believes. He’s not wrong.

The Christ Child may have wanted for an adventure playground. Certain sources allege that he had a delinquent streak. At age five, he made one of his playmates “wither like a tree,” and he struck another boy dead in the street just for bumping into his shoulder. This is the Gospel According to Catherine Nixey, whose Heretic: Jesus Christ and the Other Sons of God (Mariner Books, $32.50) pursues a fugitive Christ through the forgotten texts of antiquity. Nixey, a British journalist descended from an ex-nun and an ex-monk, wants to know how “the familiar Jesus of Sunday schools and sunbeams” emerged from a thicket of competing and often fractious accounts of his life. The New Testament, in her view, is something like The Power Broker expunged of all the sections in which Robert Moses is arrogant, racist, or conniving. “One kind of Christianity won in the West, then crushed its rivals out of existence,” she writes. “One single form of Christianity enjoyed serendipity and called it destiny. It was not.”

I’ve written in these pages about an errant nun, a philandering preacher, gospel thrillers, Mormon weirdness, and a church undone by its antiracist pieties, so it’s fair to say that I gravitate toward all that’s unholy in holiness. Heretic has the mother lode of tales too hot for Christendom. Nixey has carefully wrung out a number of apocryphal texts for scandal. Various Christian sects avowed in the early days that their savior was hotheaded, brazen, dark-skinned; that he was ninety-six miles tall and twenty-four wide; that he was venerated by dragons. Jesus may have been a magician—a number of renderings depict him with a wand—and there were those among his first believers who couldn’t decide if he ate and shat like the rest of us. Some apparently couldn’t abide that he’d let himself be crucified; the likelier story was that he’d swapped himself for another man on the cross at the last minute, laughing as his replacement died. This puckish Christ can also be glimpsed in the Acts of Thomas, an apocryphal text from the third century, in which Jesus appears like a Cheshire cat on a couple’s marriage bed. He’s there to stop them from consummating their union. Children are invariably “crippled or deaf or dumb or paralytics or idiots,” he tells them, so abstinence is the only safe bet.

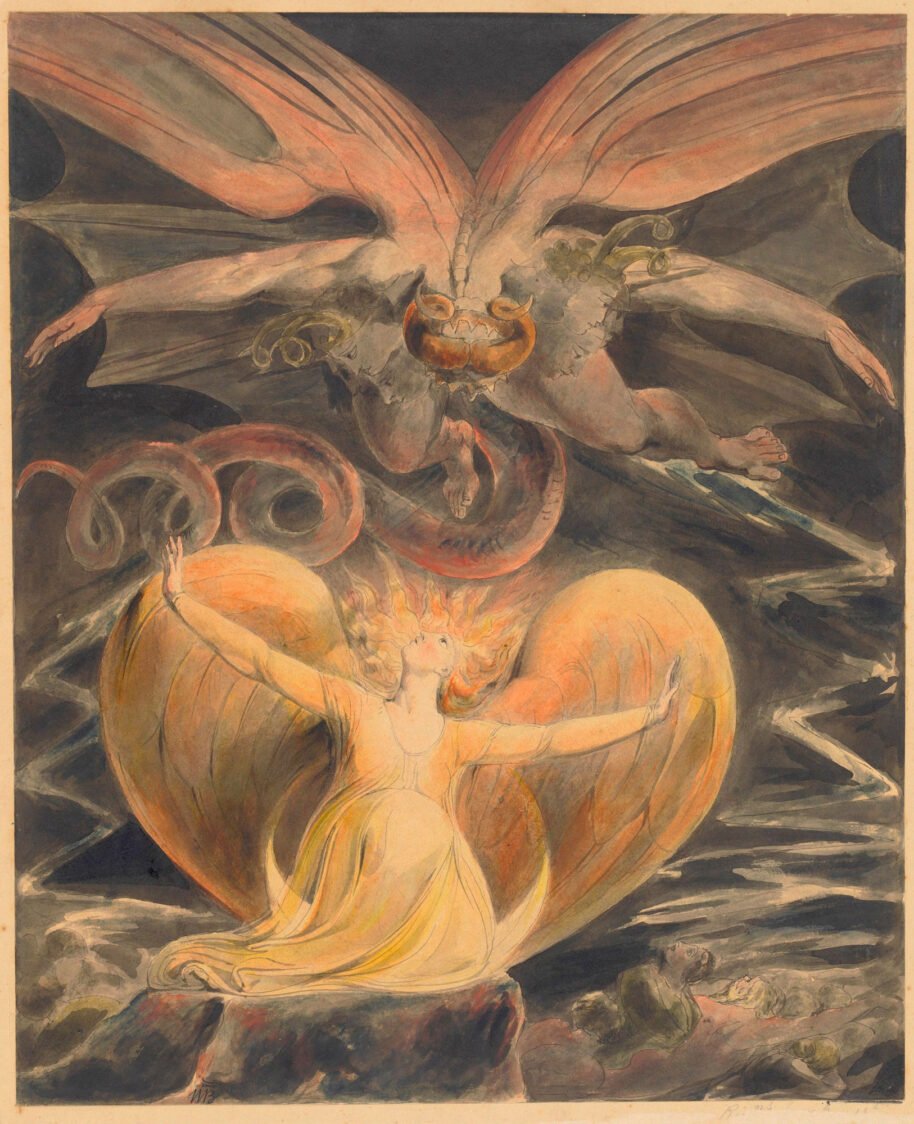

The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun, c. 1805, by William Blake. Courtesy Rosenwald Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

As for Christ’s arrival on earth, it was said that he was “pre-assembled in Heaven,” Nixey writes, and “passed through the Virgin Mary like water through a pipe”—a new kind of Piss Christ. Another theory held that Mary had been aurally impregnated: a frieze depicts “a long trumpet-like tube” connecting the mouth of God to Mary’s ear “with the foetal Jesus sliding along it.” Nixey goes deep on the Nativity. She cites the Protoevangelium of James, a largely forgotten Gospel believed to have been written in Greek around 150 that adds salt and pepper to the fairly flavorless story of Christ’s birth. In James’ rendition, all the birds in the sky freeze for a moment when Jesus is born in a cave. A woman passing by, learning of Mary’s supposed chastity, says, “Unless I thrust in my finger, and search for the parts, I will not believe that a virgin has brought forth.” Upon initiating the procedure, Mary’s anatomy burns her hand clean off. Then she repents.

Celsus, a second-century Greek philosopher and something of the Richard Dawkins of his day, supposedly compared Christian lore to lullabies that “a drunken old woman would have been ashamed to sing.” Nixey is never so impertinent, but her gist seems much the same. Still, her tour of the faith’s lesser-known byways sometimes pauses on gorgeous oddities, such as the supple masculinity in the Syriac verses of the Odes of Solomon:

The Son is the cup, and He who was milked is the Father: and the Holy Spirit milked Him: because His breasts were full, and it was necessary for Him that His milk should be sufficiently released; and the Holy Spirit opened His bosom and mingled the milk from the two breasts of the Father.

As you’ve grasped by now, Heretic is all mingled milk, a syncretic compilation of Jesus’ B-sides. It’s written for a general readership, but I can’t quite figure out whom it’s really for, other than those of us still licking our wounds from a youth in the pews. Theologians and historians may object to its breakneck pace—it tumbles through epochs and empires—and the devout will find it too irreverent by far. But the Catholic Church kept apocryphal works on its Index Librorum Prohibitorum until 1966, so they’ve got staying power. Maybe books like Nixey’s should appear a few times a century to take some helium out of the biblical balloon. It would be nice, every once in a while, to greet Jesus as a stranger.

Much as the church suppressed apocryphal works, tsarist Russia could not brook The Talnikov Family (Columbia University Press, $22), a novel censored in 1848 for its “undermining of parental power.” Strange, as this blunt instrument of a book seems to undermine everyone and everything in its pages. Even the flies and roaches are abused: “Lacking toys, we would sometimes tie a long string to a fly’s legs and follow its flight.” (Imaginative play.) There’s a butterfly on page 12, but it has a broken wing. The novel’s author, Avdotya Panaeva, wrote the book at twenty-seven and attempted to publish it under a pseudonym; apparently it’s based on her own childhood. Now it’s available in English, in a graceful translation by Fiona Bell—and grace is a major achievement for a novel that opens with the washing of a dead baby. “Only the wet nurse cried—about the gilded cap and fur coat that she had lost due to my sister’s premature death,” Panaeva writes. “If the baby had waited five or six months longer to die, the nurse’s work would have been through, and the promised reward would not have slipped through her fingers.”

Things don’t let up from there. By the end of the second chapter, four children and a grandmother have died—and these are what the narrator, Natasha, calls “the golden days of our childhood.” The Talnikovs live in a crowded St. Petersburg apartment. The patriarch stabs the dog with a fork and drinks decanters of vodka for breakfast. The matriarch insults her children’s feet (“God’s rewarded us with freaks”) and punishes them when she loses a card game. The aunts, who seem numberless, lead lives sedentary enough to “embitter even the most mild-tempered of spinsters.”

Bread, by Jacob Collins © The artist. Courtesy Adelson Galleries

That’s the plot: a portrait of drudgery so complete that it reads almost like a satire of Russian literature, what with all the drinking of jugs of kvass, whipping and being whipped, eating bread soaked in tears, etc. Natasha blends in—“like a sexless being, neither a girl nor a boy, and unloved by anyone, I was left to nature”—and watches, phlegmatic and precocious, as her days are stolen from her. Her narration is effortless, almost effervescently negative, and her story ends with a marriage that feels like a prison break. Some of Panaeva’s sentences read like hidden messages in an old dollhouse, or Jenny Holzer billboards: “Their conversation consisted of the transfer of mutual suffering.” I see why the censor was spooked. The novel doesn’t exactly make one wish to run out and procreate. But then, Jesus warned us about that.