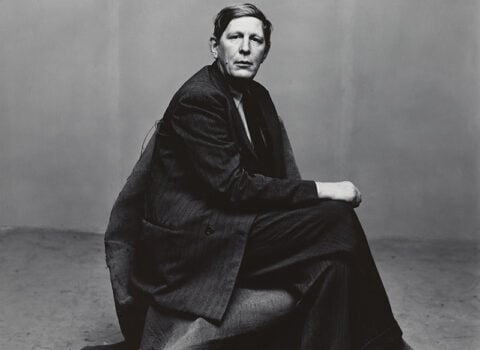

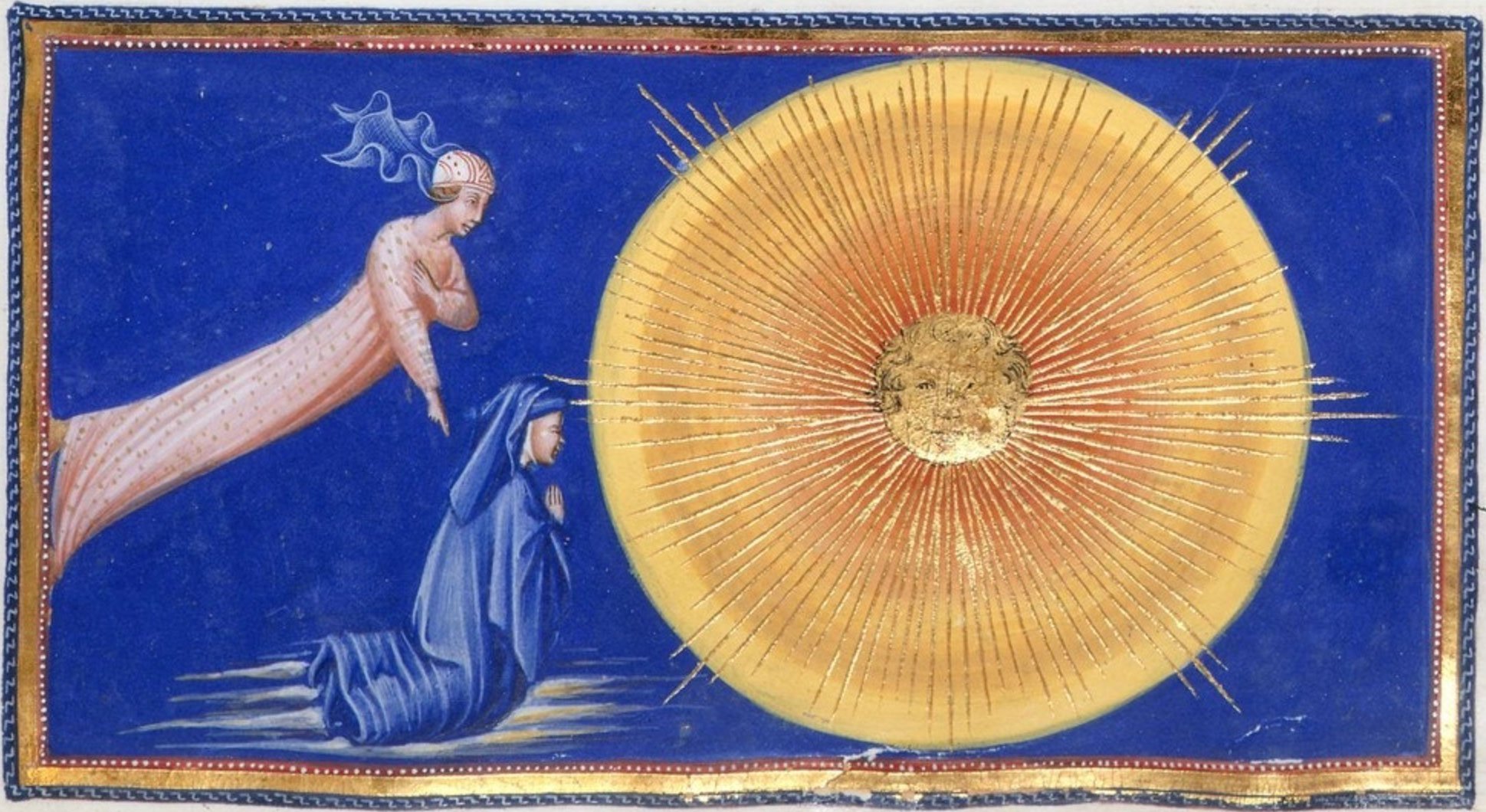

A miniature depicting Dante and Beatrice, by Giovanni di Paolo di Grazia, from a fifteenth-century edition of Dante’s Paradiso. Courtesy the British Library

Discussed in this essay:

Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays, by Northrop Frye. Princeton University Press. 408 pages. $22.95.

The New Science, by Giambattista Vico. Translated from the Italian by Jason Taylor and Robert C. Miner. Yale University Press. 480 pages. $28.

The Hero with a Thousand Faces, by Joseph Campbell. New World Library. 432 pages. $24.95.

One day in the autumn of 1980, during my first semester of graduate school, I was making my way to the English department when I came across a classmate. He was sitting on a bench, holding papers in his hand, and staring at nothing. When I asked him what was up, he told me that one of his professors had just returned a graded paper to him—the first paper he had written as a graduate student—and told him that he had inappropriately relied on the ideas of a literary critic named Northrop Frye. The professor had written that Frye was “yesterday’s man.” “Yesterday’s man,” my classmate repeated. “What does that even mean?”

Not so many years earlier, Frye had been the most important literary critic in the English-speaking world. But now he was increasingly being overshadowed by figures with strange names like Barthes and Derrida. A few weeks before my college graduation, a professor took me aside and whispered those names into my ear; feeling myself welcomed into some new freemasonry, I fetched an index card and wrote Bart, Derry Da. Only that initiation had prevented me from suffering a fate like that of my befuddled classmate. I tried to be sympathetic, not smug.

Frye, in his magnum opus, Anatomy of Criticism, had conceived of myth, archetype, ritual, and symbol as forming a cathedral-like structure in which every literary work finds its place, much as every redeemed soul finds its place in the mystical rose at the end of Dante’s Commedia. By linking this symbol in Virgil to that symbol in Percy Shelley, this echo of ancient ritual in Shakespeare to another one in George Eliot, Frye sought to create a taxonomy of the literary imagination—a project satisfying to the tidy-minded and the spiritually hungry alike.

But then, we were told, Jacques Derrida had come around to show that all structure somehow deconstructs itself. We didn’t quite know what that meant, but it sounded definitively dismissive, and the thought of becoming yesterday’s men and women at the age of twenty-two was distressing. We quickly adjusted—or else departed.

Another of those names to conjure with, Michel Foucault, had asserted that some thinkers are “founders of discursivity”: a key importance of their texts lies in their ability to generate many other texts. It is a power they have until their work has been exhausted. For instance, the ideas of Sigmund Freud were for several decades so dominant that W. H. Auden could write in a memorial poem that Freud was not a person but a “climate of opinion,” but eventually these ideas lost their aura of inevitability. Similarly, Frye—who reigned for a much shorter period and in a much narrower sphere of cultural production—had become, well, yesterday’s man. His literary theory of everything now seemed to account for nothing.

Once a founder of discursivity ceases to inspire, it is natural to wonder why their work ever appealed in the first place. Why did people respond to it? What was it about myth criticism, as exemplified by Frye and certain others, that made it so compelling throughout the third quarter of the twentieth century? What needs did it meet? What questions did it answer? Why did it disappear? And—I wonder—might we consider bringing it back, at least in some form?

To search for the source of any influential idea, or set of ideas, is a mug’s game, because even the most original thinker has debts. We might begin almost anywhere. So let’s begin with a disappointed academic at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Giambattista Vico studied law at the University of Naples, aspiring to become a professor in that subject. But his hopes failed, and he became a professor of rhetoric instead—then as now, a position less rewarding, financially and reputationally. Bemoaning his obscurity, Vico nonetheless continued his labors and, in 1725, produced the first version of an astonishingly ambitious work, one whose title he would change over the years. In its final recension in 1744, it was called Giambattista Vico’s Principles of New Science Concerning the Common Nature of Nations.

One of Vico’s chief claims is that, though civilizations rise and fall, the periods of decline do not return them to their original state. Some foundation remains from which rebuilding can commence. A central challenge for a science of politics, then, is to reduce the severity of the inevitable downturns, shorten the reign of “barbarism,” and through these means, hope for gradual improvement. Such hope he finds necessary for religious reasons if for no others: as he says in the book’s final sentence, “If one is not pious, one cannot in truth be wise.”

Vico believed that our declines are so often disastrous because we neglect the wisdom of our ancestors. He describes the twelfth century as a barbaric era, but argues that, in France anyway, such barbarism was countered by Peter Lombard’s “most subtle” theology on the one hand and, on the other, the ongoing influence of the eighth-century bishop Turpin’s historical writings, which “abounded in . . . myths.” (Vico means that as a compliment.) Vico applauded these authors for drawing on their cultural inheritance. By contrast, philosophers of Vico’s own time—that is, Descartes and his successors—were indifferent to such things as myth, focusing instead on the analysis of abstract principles. Vico worried that introducing students to too rigidly conceptual modes of thinking constituted a “barbarism of the intellect,” warning that “a metaphysical art of criticism and algebra” could render them “too attenuated in their manner of thinking for the full scope of life.”

Vico believed that those who lacked a rationalist philosophical apparatus like Descartes’s did not necessarily lack philosophy, metaphysical insight, or wisdom. Their wisdom was just of a different order—what Vico calls “poetic wisdom” and sees embodied, supremely, in Homer. Such poetic wisdom is the product of vast cultural movements, rather than of individual genius; Vico believed that Homer was not a historical person but simply the name given to the collective poetic wisdom of the Greek people. He intimated that lasting progress could be made only through a scienza nuova that unites modern thought with a historical understanding of the role of poetry and myth in shaping culture. Myths, for Vico, were not merely false stories that could be safely ignored by the rational, but rather exercises in metaphysical ingenuity, capable of preserving and transmitting vital wisdom.

In making the case for the importance of myths, his goal was to achieve a universal philosophy. But such a philosophy could be fruitfully pursued only by understanding mythmaking practices and noting their variance from culture to culture. It was through deep philological research that we could come to understand myths and the ways they rhyme across cultures. Philology, in tracing the development of images, myths, and concepts in a given language, prepares us to make comparative studies of societies—which in turn would allow for a philosophy both grounded in eternal verities (what Vico called “the true”) and attentive to individual contingencies of the real world (“the certain”). Philological particularity, Vico believed, was the royal road to universal knowledge. 1

Vico was not widely read in his time, but his ideas slowly made their way into European circulation. And though his ideas were altered in the process of reception, Vico came to inspire what Isaiah Berlin called the Counter-Enlightenment, a late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century movement shaped by a fascination with the distinctive forms taken by various societies, as well as a syncretic interest in myths of the sort found in the New Science. A characteristic figure of the early Romantic era, Berlin argued, is the eighteenth-century protosociologist Justus Möser, who believed that Zeitstil (the style of the time) and Volksstil (the style of a particular people) “are everything; that there is a local reason for this or that institution that is not and cannot be universal.”

Such thinking (notice the word Volk) is certainly linked to the rise of German nationalism. But it isn’t linked only to that. The nineteenth century was a boom time for Christian missionary activity, which spread the gospel to cultures newly encountered by Europeans and white North Americans, but it was also a period of increasingly vocal hostility to missionaries among European intellectuals. Such hostility was sometimes humorous—think of Dickens’s easy mockery, in Bleak House, of Mrs. Jellyby’s obsession with “the natives of Borrioboola-Gha, on the left bank of the Niger”—and sometimes more serious, particularly when pronounced by those new creatures, anthropologists. For a progressive contingent of the latter, the diversity of the world’s cultures served the case against the missionary movement; surely there was no good reason to impose the Christian mythos upon other cultures that had perfectly functional mythoi of their own.

Berlin calls Möser “the first historical sociologist,” but there is a direct line from concepts like Zeitstil and Volksstil to modern cultural anthropology, a discipline whose adherents have often credited themselves for breaking with Western cultural imperialism. Consider, for instance, Ruth Benedict’s Patterns of Culture (1934), which argues that one “elementary postulate of anthropology”—the conviction that we cannot truly study culture if we insist upon “distinctions between ourselves and the primitive, ourselves and the barbarian, ourselves and the pagan”—simply “could not occur to the most enlightened person of Western civilization” until late in the nineteenth century.

In the typical anthropological account, myths, among all the practices that constitute culture, have the distinctive role of explaining and justifying other practices. And cultural anthropology, with its insistence on the many varieties of cultures, was committed to noting the sheer diversity of mythologies. But this commitment would come to be questioned by two massively influential figures who agreed on little besides their Viconian interest in the “common nature” of human cultures: a Scot named James George Frazer and a Swiss named Carl Jung.

As cultural anthropology developed, it became evident to anthropologists that certain practices and stories tended to appear across cultures. They came to call those practices rituals and those stories myths, though the latter term has proved slippery. One of the most admired books on the subject, Myth (1970) by G. S. Kirk, is typical in its annoyance with all previous scholarship on the subject. “Nearly everyone thinks he knows what he means by a myth,” Kirk writes. The belief shared by Frye and many others that myths are stories about gods? “Easily disposed of.” W.K.C. Guthrie’s implication that mythology is an aspect of religion? “Misleading.” Ernst Cassirer’s view that myth is always potential religion? “Wholly unjustified.”

“Myths are at the very least tales that have been passed down from generation to generation, that have become traditional”—this, for Kirk, is a bold statement. But he accepted French sociologist Émile Durkheim’s functionalist view of cultural practices: namely, that they strengthen the bonds of community. Myths fulfill this function in multiple ways: some mythological stories explain, some exhort or warn, some inspire, and some simply provide communal entertainment, which itself has a binding power.

But the similarities between the myths of different cultures called for explanation. Why, for instance, did so many cultures have stories of gods who die and are reborn? Frazer takes up this question in The Golden Bough, which began as a two-volume study (1890); expanded to three; over a decade metastasized into a dozen; was contracted into a single, drastically abridged book; and finally culminated, nearly fifty years after its inception, in an addendum called Aftermath (1936). In what one hopes was an intentional irony, Frazer wrote in a preface that “the primary aim of this book is to explain the remarkable rule which regulated the succession to the priesthood of Diana at Aricia.” The inquiry began when Frazer was confused by a passage in Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid, in which the Sibyl tells Aeneas that, to gain entry to the underworld, he must take a bough from a tree in a grove sacred to Diana. Looking into this story (which seems to have been brought to his attention by a Turner painting of the scene), Frazer uncovered an odd story:

On the northern shore of the lake, right under the precipitous cliffs on which the modern village of Nemi is perched, stood the sacred grove and sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis, or Diana of the Wood. . . . In this sacred grove there grew a certain tree round which at any time of the day, and probably far into the night, a grim figure might be seen to prowl. In his hand he carried a drawn sword, and he kept peering warily about him as if at every instant he expected to be set upon by an enemy. He was a priest and a murderer; and the man for whom he looked was sooner or later to murder him and hold the priesthood in his stead. Such was the rule of the sanctuary.

It struck Frazer that this priest bore the title of king (the Rex Nemorensis, in the original, King of the Wood). It did not escape his notice that the idea of a priest-king being slain for the good of the people was a reasonably accurate summary of what had happened to Jesus Christ. He wrote to his publisher:

the resemblance of the savage customs and ideas to the fundamental doctrines of Christianity is striking. But I make no reference to this parallelism, leaving my readers to draw their own conclusions.

Further study led to the discovery of some version of this story in cultures all over the world.

Frazer concluded that all such tales reflect the character of agricultural life and mark the seasonal patterns of life and death, as embodied in a “corn-spirit”—essentially the same deity, whether called Tammuz (among the Mesopotamians), Adonis (among the Greeks), or John Barleycorn (among the English and Scots). Beneath the diversity, Frazer saw a potent unity of purpose, something close to a universal myth.

The Golden Bough, c. 1834, by J.M.W. Turner. Courtesy the Tate

Frazer’s understanding of history was largely progressive. He believed that primitive magic gave way to religion, religion to science, and that this sequence moved generally from the more false to the more true. But many of the people convinced by his argument—belated Viconians, enamored of “poetic wisdom”—were not anthropologists but novelists and poets. T. S. Eliot, when asked to turn The Waste Land into a book, did so by appending detailed notes, including this one:

To another work of anthropology I am indebted in general, one which has influenced our generation profoundly; I mean The Golden Bough; I have used especially the two volumes Adonis, Attis, Osiris. Anyone who is acquainted with these works will immediately recognize in the poem certain references to vegetation ceremonies.

Decades later, Eliot would refer to these notes as a “remarkable exposition of bogus scholarship,” but they offer a telling glimpse into his mind at the time. In 1923, the year after he completed The Waste Land, he wrote that James Joyce’s Ulysses had been an attempt to give “a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history.” That attempt, Eliot claimed, was based on “the mythical method,” which represented “a step toward making the modern world possible for art.”

Jung despised Frazer as intensely as Eliot admired him. Though Jung acknowledged that “the whole mythological complex of the dying and resurgent god” is “a well-known primordial image that is practically universal,” he contested Frazer’s explanation for its universality:

One is naturally inclined to assume that seasonal, vegetational, lunar, and solar myths underlie these analogies. But that is to forget that a myth, like everything psychic, cannot be solely conditioned by external events. Anything psychic brings its own internal conditions with it, so that one might assert with equal right that the myth is purely psychological and uses meteorological or astronomical events merely as a means of expression.

For Jung, internal, not external, conditions produce myths; the psyche looks for correspondences in the seasonal and vegetational world, seizing on them as vehicles for describing inward experiences. Agricultural explanations for such myths can, therefore, never be universal enough—after all, agriculture itself is not universal across human societies. Though “certain conditions are needed to cause [a primordial image] to appear,” Jung insisted that one should not confuse their inciting situation with their underlying origin. The true “primordial images” have been “stamped on the human brain for aeons,” which is why they remain “ready to hand in the unconscious of every man.”

Adolf Hitler emerges as a force in German politics and society at almost the same moment that The Waste Land and Ulysses appear, and what we see in Hitler, and indeed the entire Nazi program, is a different sort of “mythical method.” Whereas Justus Möser had insisted on the validity of local cultural styles and practices, refusing to make universal judgments, Nazism makes the Volk national, not local, and declares that one particular Volk is genetically superior to others—a superiority made manifest in its mythological inheritance—and thus must rule over them.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, there arose among Western democracies a fear of all narratives that divide and exclude—of what today we call identity politics, even if the relevant identities were different than those that now occupy us. Western artists and intellectuals, sensing the dangers of a mythical method that relies on qualitative distinctions between one culture and another, felt the need for a reinforced humanism, a stress-tested account of what links and binds all human beings. Indeed, there had been some question of whether the war against the Nazis could be won without such a humanism, of which the 1943 pamphlet The Races of Mankind, by Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish, was representative. In it, they argue that no race is superior to another; that all humans have the same capabilities and deficiencies; and that, therefore,

the Bible story of Adam and Eve, father and mother of the whole human race, told centuries ago the same truth that science has shown today: that all the peoples of the earth are a single family and have a common origin.

The appeal to Scripture might seem out of place, but the pamphlet was meant for the average citizen, and the Public Affairs Committee, which had published it, persuaded the U.S. Army to distribute it to officers as “background material to help counteract the Nazi theory of a super-race.” (Its emphasis on racial equality, however, roused the ire of a certain Southern congressman.)

This pursuit of a new humanism continued after the war in many forms, from the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights to The Family of Man, an exhibition of more than five hundred photographs that toured the world between 1955 and 1963, to great acclaim from the public and great scorn from many intellectuals. Roland Barthes wrote an especially fierce denunciation of it; tellingly, he attacked what he called “this ambiguous myth of the human ‘community,’ which serves as an alibi to a large part of our humanism.” But for those who might have been more Viconian than Barthes, myth was precisely what was needed in our highly rationalized (not to mention bureaucratized) social world: a compelling and integrated body of stories capable not so much of telling as showing us our common humanity.

The exponents of myth seemed to shout from every street corner. The year 1946 saw the appearance in English of Ernst Cassirer’s Language and Myth, a book published in Germany in 1925. By the late Forties, Auden was examining the distinctive power of “mythopoeic” writing. In 1949, the Romanian scholar Mircea Eliade, then living in exile in France, published Le mythe de l’éternel retour: archétypes et répétition; its translation as The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History led to Eliade’s appointment in 1957 to a professorship at the University of Chicago, where he would write much more about myth. (His lifelong fascist sympathies have received greater scrutiny since his death.) And then—above all—there was Joseph Campbell.

Campbell, who taught literature at Sarah Lawrence College, published in 1949 The Hero with a Thousand Faces. There was no way for him to know that his monograph would eventually become the book that launched a thousand science-fiction stories, though it was unusually ambitious for a scholarly treatise. That ambition arose from Campbell’s study of Joyce, whose own mythical method Campbell recognized as deriving from the work of Vico. In 1944, Campbell and the novelist Henry Morton Robinson had published A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, one of the first serious attempts to grapple with that formidable text, which Joyce had published just five years earlier. In particular, Campbell and Robinson noticed that the first sentence of Finnegans Wake (which is a continuation of its last sentence) contains the phrase “a commodius vicus of recirculation,” which points both to the name Vico and to the idea of cyclical history. Cyclical repetition, per Campbell and Robinson, is congruent with simultaneity: if patterns could appear in the same place at different times, then it stood to reason that they could also appear in different places at the same time—especially if Jung’s notion of the “collective unconscious” was correct.

From these thoughts sprung Campbell’s key concept, which he called the “monomyth”—the myth that appears everywhere and everywhen. In the monomyth, he wrote:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

For decades, Campbell elaborated this theme, despite complaints from other scholars that myths would naturally seem identical if one ignored everything that made them different. 2 Campbell remained unmoved by such critiques, as did his millions of readers—and viewers, after Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth, a series of six dialogues with Bill Moyers, became a hit on PBS. But television would discover Campbell only at the end of his life, in the Eighties, long after the apostles of myth had become, at least in the academy, yesterday’s men. In the Fifties, though he was the most popular of the many proponents of myth, he was perhaps not the most influential. That title may well have belonged to Northrop Frye.

Frye—an English professor at the University of Toronto and a minister in the United Church of Canada—owed nothing to Campbell. His understanding of the “power of myth” derived primarily from his careful study of Blake, about whom he wrote his first book, Fearful Symmetry. The end of that volume sees Frye rise to a peroration that virtually summarizes what I have written so far:

The age that has produced the hell of Rimbaud and the angels of Rilke, Kafka’s castle and James’s ivory tower, the spirals of Yeats and the hermaphrodites of Proust, the intricate dying-god symbolism attached to Christ in Eliot and the exhaustive treatment of Old Testament myths in Mann’s study of Joseph, is once again a great mythopoeic age. In Finnegans Wake, apparently, we are being told once more that the form of reality is either that of a gigantic human body or of an unending series of cycles, and that the artist’s function is to achieve an epiphany of the former out of the chaos of nature and history. Here again is a work of art in which every letter as well as every word has been studied and put into its fit place, which is a puzzle to the intellectual powers and utter gibberish to the corporeal understanding.

A decade later, in Anatomy of Criticism, Frye provided a theoretical scaffolding for these scattered insights into the great Romantic and post-Romantic artists. Here he would make literary criticism a “science”—that is, a Scienza Nuova of criticism, built on a quasi-Jungian study of myth as intrinsic to the deep structures of human consciousness, where archetypes dwell.

These pages show Frye’s mind and technique to be endlessly associative and taxonomic, always weaving patterns between archetypally related texts. He “stands back” from those texts, as he put it in the Anatomy, to see their common features. The approach yielded many passages like this one:

The vegetable world is a sinister forest like the ones we meet in Comus or the opening of the Inferno, or a heath, which from Shakespeare to Hardy has been associated with tragic destiny, or a wilderness like that of Browning’s Childe Roland or Eliot’s Waste Land. Or it may be a sinister enchanted garden like that of Circe and its Renaissance descendants in Tasso and Spenser. In the Bible the waste land appears in its concrete universal form in the tree of death, the tree of forbidden knowledge in Genesis, the barren fig-tree of the Gospels, and the cross. The stake, with the hooded heretic, the black man or the witch attached to it, is the burning tree and body of the infernal world. Scaffolds, gallows, stocks, pillories, whips, and birch rods are or could be modulations. The contrast of the tree of life and the tree of death is beautifully expressed in Yeats’s poem The Two Trees.

The assurance with which Frye announced these and many other correspondences granted him an aura of authority that many readers found irresistible. And such authority was much coveted by humanists who felt outclassed (and greatly out-funded) by the scientists and engineers who had recently won the Allies the war. Frye had become a founder of discursivity, the leading humanist scholar of his time. His belated Viconianism ruled the day—until it didn’t.

What happened? In brief: the Sixties. The political upheavals of that decade called into question every humanism, old and new. What was humanism but an attempt to universalize and install the preferences of the ruling class, the chief members of which were white, male, and Western? The great question of the Sixties (or what we now think of as the Sixties, which was the period between 1967’s Summer of Love and the Watergate hearings in the early Seventies) was Lenin’s question: Who whom? What is this one trying to do to that one? Who benefits from the promotion of myth as the means of achieving true humanism, and at what cost to whom? As the activists and rebels of the Sixties moved through graduate school and into the academic profession, they continued to ask these questions, insisting that their predecessors had sold us a bill of goods.

Nowhere was this point made more forcefully than in what is undoubtedly the best-selling book ever written about literary criticism, Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983). Here Eagleton argues that Frye’s work “is marked by a deep fear of the actual social world, a distaste for history itself,” and is primarily an exercise in nostalgia:

The mythoi of [Frye’s] theory are, significantly, pre-urban images of the natural cycles, nostalgic memories of a history before industrialism. Actual history is for Frye bondage and determinism, and literature remains the one place where we can be free.

Frye’s science of criticism combines “an extreme aestheticism with an efficiently classifying ‘scientificity’ ” and “maintains literature as an imaginary alternative to modern society while rendering criticism respectable in that society’s terms.” Eagleton’s criticism, along with the chorus of politically inflected criticism that echoed (or anticipated) it, struck a blow against myth criticism from which the practice never recovered. More generally, the study of myth came to seem like an evasion of political realities.

But the Sixties did not bring an end to the fascination with myth, even though the subject certainly moved out of the academy and into mainstream culture. Myth became less a repository of deep meaning—a Viconian poetic wisdom—and more a vehicle for aesthetic pleasure, both “high” and “low.”

Take, for example, the poet James Merrill and his partner David Jackson, who for decades used a Ouija board to develop an intricate mythology that featured spirit guides, recently deceased friends (including Auden), fallen angels that appear as blue-eyed bats, and a “God Biology,” who appoints Merrill to renovate the house of man. As descriptions of their encounters with these figures mount, they become increasingly abstract, didactic, and unpoetic, an exercise in system building for its own sake. Initially, though, Merrill seems to have had something more humanistic and artful in mind. Take this passage from his book-length poem The Changing Light at Sandover:

Looking about me, I found characters

Human and otherwise (if the distinction

Meant anything in fiction). Saw my way

To a plot, or as much of one as still allowed

For surprise and pleasure in its working-out.

Knew my setting; and had, from the start, a theme

Whose steady light shone back, it seemed, from every

Least detail exposed to it. I came

To see it as an old, exalted one:

The incarnation and withdrawal of

A god. That last phrase is Northrop Frye’s.

These lines were composed a few years before Frye became yesterday’s man. But—and this is the kind of question that Frye, too, was often asked—did Merrill really believe in the god who incarnated and withdrew? Did he think that he and Jackson were being initiated into the real shape of the hidden world?

Merrill was given a Ouija board in the early Fifties by his friend Frederick Buechner, who later became a distinguished novelist and a Presbyterian minister. I knew Buechner, and in a long-ago conversation he told me that he had meant the gift as a joke and was appalled by how seriously Merrill took it. He once asked Merrill the inevitable question: Do you think you are communicating with spirits from beyond this world? To which Merrill smilingly replied, “Does it matter?” Buechner told me that he had let the subject drop but later wished he hadn’t, because, he reflected, “Of course it matters. It matters more than anything.” But Merrill seems genuinely not to have cared. For him, the board offered an avenue for playful aestheticism, generating as it did an ordered sequence of images, what Wallace Stevens called a “supreme fiction”: something meant “to confect / The final elegance, not to console / Nor sanctify, but plainly to propound.”

Campbell, too, seems to have arrived at a similar conclusion about the fundamental reality that myths might link us to. If divinity is “just what we think,” Moyers asked him in The Power of Myth, “what does that do to faith?” “Well, it’s a tough one about faith,” Campbell replied. But there still remained an afterlife for his work: the director George Lucas claimed that the monomyth was an inspiration for the plot of the Star Wars movies. (Five of the six interviews that make up The Power of Myth were recorded at Lucas’s Skywalker Ranch in northern California.) Whether Campbell really was so influential for Lucas has been doubted, but the monomyth has cast a long shadow over Hollywood, starting with Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters, a book published in 1992 that has since become a bible for many in the industry.

Thus we see the fortunes of the study of myth: the endeavor that Giambattista Vico thought essential to the acquisition of wisdom, that T. S. Eliot hoped could rescue meaning from the chaos of the modern world, has been reduced to fodder for scriptwriting manuals. Sic transit gloria mundi.

Should we regret the passing of the mythical method, of mythology in its etymological sense of discourse about myths and mythmaking? Perhaps the question is misleading: mythmaking is alive and well—if by that we mean the creation and sharing of stories that are meant to orient us, morally and emotionally, to our world and are resistant to restatement in straightforward conceptual terms. But taken differently, the question reveals just how the decline of myth criticism has tended to render our own myths invisible to us as myths. They may appear to us, but they do so in false guises, as science perhaps, or as politics, or as administrative procedure.

Today, none of our regnant myths produces a sense of what Barthes contemptuously called “the human ‘community’ ”—they are not in the business of universality, of grounding and justifying humanism, of making a family of man. Such endeavors can seem—like Maya Angelou’s poem “Human Family”: “We are more alike, my friends, than we are unalike”—fit chiefly for greeting cards and Pinterest boards.

And yet. Though the study of myth emerged from the discovery of cultural diversity, the mythical method of the twentieth century arose from a desperate hope to bridge the chasms of hatred and fear that separate humans from one another. Fact and argument alone cannot build forbearance and charity across racial and cultural and sexual boundaries; this requires image and event, the visualizable and the narratable, picture and story. One can see that the attempt failed while admitting and even embracing its nobility.

Have we lost the knack or the appetite for such stories? For tales of wounds that do not heal, kings who sacrifice themselves for the good of the people, slaves who are really princes, peasants whose generosity is known to the gods—and gods who die and are born again? Perhaps. But it was not so long ago that some of our best writers were drawn to them. A knack lost may yet be regained.

Let me conclude, then, not with a myth, or even an argument, but with a mere story, a narrated event, an exemplary tale. Many years ago, I visited a place in Nigeria called the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove. Osun is a fertility goddess of the Yoruba people, and in this eerie but beautiful sanctuary stand statues of several gods, or orishas, chief among them Ogun. In one telling, Ogun, the god of iron, was the first orisha to come to this world. Instead of returning straight to the spirit world, he descended into the earth, so that those who found the spot where he entered the earth could recall him and receive aid. It’s also said that if one kisses a bar of iron while invoking Ogun, one’s testimony is true.

In 1965, the great Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka wrote “Idanre,” an extended ode in the tradition of the ancient Greek poet Pindar. It is a sober and awestruck celebration of Ogun’s coming to our world and a fearful account of his death, which Soyinka, who was raised Christian, calls a “Passion.”

The moment of its publication was significant. For the Nigerian independence celebrations in 1960, Soyinka had written a play, A Dance of the Forests, that was anything but celebratory. Throughout it, “two spirits of the restless dead,” a man and a woman, repeatedly plead unto the living, “Will no one take my case?” The repetition suggests the indifference of the living. In the context of an independence celebration, this may seem strange, but with it Soyinka had issued a warning to his country’s rulers. Over the next few years, he would decry the ways that the political elite of the newly liberated nation had replicated the hierarchies of the departed colonial power. His anger moved him to link the staggeringly complex myths and rituals of the Yoruba people with the equally complex myths and rituals known to Pindar. Through this renewed mythical method, he sought to make sense of “the immense panorama of futility and anarchy” that he saw around him—to make sense of it, transcend it, perhaps even correct it.

A few years later, Soyinka would translate The Bacchae, Euripides’ play about Dionysus and the cult that bore his name. Soyinka created an extraordinarily beautiful and harrowing drama that unites Greek myth with Yoruba myth. In Euripides’ Greek and Soyinka’s English, the play concerns the terror that the gods inspire and the impossibility of ever eluding that terror; it delineates the political and social repercussions of possession. Again drawing on Christianity, Soyinka subtitled his play “A Communion Rite”—but communion with whom? And to what end? Soyinka’s Bacchae is a serious work of art in a way that almost nothing done these days is serious, and its power derives from its merging of three seemingly quite different cultural traditions—three distinct and yet mystically correspondent practices of mythmaking. It is a humanist gesture, though a chastened one: skeptical and yet hopeful. At the heart of it is the insistence that we need not escape myths but rather make better, wiser use of them.

Soyinka has added to Euripides’ play a second chorus: not just the Bacchae (the worshippers of Dionysus) themselves, but also a group of slaves. He insisted in a production note that the Bacchae and the slaves alike “should be as mixed a cast as is possible, testifying to their varied origins.” And, he added, in making his translation, he has incorporated, verbatim, passages from his poem “Idanre.” After all, he wrote, Ogun is the “elder brother of Dionysos.”