When the world tunes in to figure skating during the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, we’ll all learn that the Iceberg Skating Palace is built atop what was once a protected coastal marshland frequented by migrating birds. We’ll hear about Vladimir Putin’s vicious antigay laws, and about how Russia spent $51 billion to turn Sochi, a temperate beach town, and the mountains nearby into the site of what may be the most corrupt Olympics in history.

But the TV crews will likely miss a complex sideshow — a place with its own history of Russian heedlessness and malfeasance. Five or so miles from the gleaming, blue-windowed Iceberg, the silky-smooth pavement of Sochi ends and the potholes begin. This is the border with the Republic of Abkhazia. Among the drug-sniffing dogs used to check cars coming and going, there’s a German shepherd who hops around on three legs. Russian guards stand nearby, laughing, smoking cigarettes, and aimlessly pacing in their stiff gray woolen overcoats.

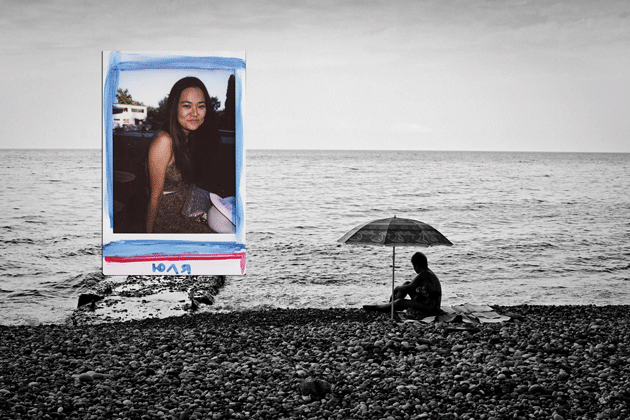

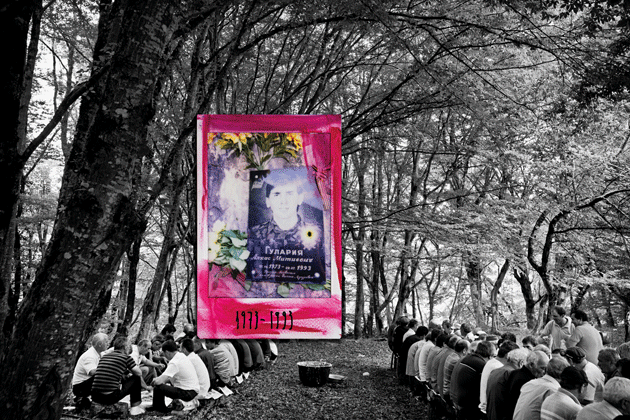

A memorial gathering at the site of the Battle of Gumista, and a gravestone of a fallen Abkhazian soldier (inset). All photographs © mirzOyan

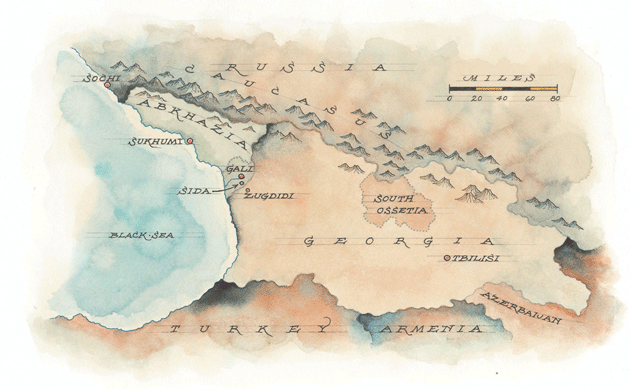

The United States does not recognize the Republic of Abkhazia, and in fact, only Russia and four of its other client states do: Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Tuvalu and Nauru, two tiny South Pacific nations with about 10,000 citizens apiece. The official U.S. position is that Abkhazia, which was once part of the Soviet Union, is now a rogue, breakaway region of Georgia.

Abkhazia is about the size of Puerto Rico and has a population of 240,000. It seceded from Georgia in 1992, and then, with military assistance from the Russians, it battled Georgia in a thirteen-month war of independence that killed 4,000 people on each side. The nation’s population was cut almost in half as 200,000 ethnic Georgians fled the country. Russia now sends Abkhazia around $100 million in aid each year, mostly for road building (despite appearances at the border) and schools.

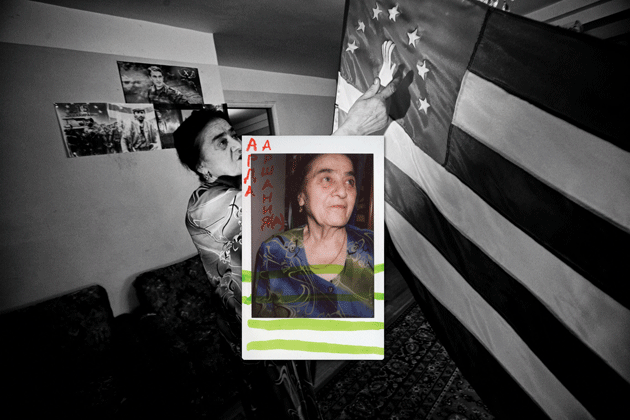

When Abkhazia and Georgia threatened to go to war again in 2008, John McCain made the U.S. position clear. “We are all Georgians,” he said. “The thoughts and the prayers and support of the American people are with that brave little nation.” In 2010, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton protested the heavy Russian presence in Abkhazia, which now hosts five Russian military bases and 5,000 Russian soldiers, calling it “occupied ground” during a visit to Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi.

Today, Abkhazia’s economy depends largely on Russian tourism. And while Russia has allowed Abkhazia to keep Georgia at bay, it has also kept the country in a state of arrested development — an independent nation in name only, reliant on its powerful patron to claim its disputed part of the world map.

The capital of Abkhazia is Sukhumi, population 63,000. It sits ninety minutes south of Sochi. The bus from the Russian border costs $4.50, and it sweeps along a winding road that looks out onto the Black Sea. The land by the roadside is a deep green, and everywhere there are ruins from the war — empty concrete buildings with grass and trees growing inside them.

Although there are bullet holes in many of the buildings, Sukhumi still feels like a resort town. Vendors sell cold drinks and T-shirts along the boardwalk, and locals sit at cafés and sip their cappuccinos slowly, gazing at the water.

Credit cards do not work in Abkhazia, and there are only a handful of ATMs. The prospects for non-Russian international investment are almost nil, said Alexei Kuzmin, a political scientist at Moscow State University for the Humanities. “Do you really think someone’s going to sweep in and invest millions in Abkhazia’s mandarin-orange crops?” Still, in Sukhumi, some businesses are thriving: there are at least six “IKEA stores,” each one a private enterprise unaffiliated with the IKEA mother ship but stocked with genuine IKEA products bought seven hours away, in the Russian city of Krasnodar.

Near the center of town is Freedom Square, a weedy expanse of grass that abuts the parking lot for SovMin, a twelve-story, Fifties-era building with tiny windows that once served as the seat of Abkhazia’s Georgian-run government.

In September 1993, in the war’s decisive battle, the Abkhazian army turned their machine guns on SovMin, firing until all the Georgians within were either driven out or killed. At night now, SovMin is lit from beneath by floodlights. When you pass by it and see its white façade looming in the darkness, the site looks almost beautiful, but inside, trash is everywhere — condom wrappers, shattered bottles, rusty box springs.

On one crumbling wall, someone has stenciled the question are you a worthy son of apsny? The last word is Abkhazians’ name for their land. Apsny is a close linguistic cousin of apsuara, the country’s unwritten code of honor. Embraced equally by Abkhazia’s Christians and Muslims (the latter make up about 15 percent of the population), apsuara shapes everything from burial rituals to table manners.

“During the war,” Lana Basaria, a university student and interpreter, said recently, “we practiced apsuara. We buried our enemies like human beings, even though we got our own bodies back in horrible condition — so horrible that even mothers couldn’t identify them. We live by apsuara. Once when a foreign diplomat visited our president’s home wearing shorts, he was turned away. We live by apsuara.”

Basaria is slender, with black eyebrows and pale skin. She speaks English with a crisp British-inflected accent; two of her aunts are among Abkhazia’s most sought-after teachers of English.

Basaria was born a month before the war ended, but she spoke frequently and with pride of how, in 1992, on the first day of fighting, her father went into battle armed with nothing but a knife. She also told the story of the eve of the war, when Abkhazia’s future president, Vladislav Ardzinba, called Eduard Shevardnadze, Georgia’s head of state. “Tell me as a person,” Ardzinba said, according to Basaria, “are you going to invade us?”

“No, you can sleep in peace and quiet,” said Shevardnadze.

The bombing began the next morning.

“In people’s minds, the war is still fresh,” she said. “We cannot forget.”

* The Russian Embassy supplies Abkhazians with Russian passports for travel to countries that don’t recognize their independence. Abkhazia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs provides locals with two additional passports — a green one for internal use, and a special blue passport that they can use on the off chance they jet off to, say, Tuvalu.

When Basaria traveled recently to Hungary, for a youth peace conference, she met a few Georgian students.* “One of them came up to me and started speaking Abkhazian,” she said, “and I just thought, ‘Okay, you speak Abkhazian. So what?’ I tried to ignore him. At the end of the meeting, they all hugged me and said how much they loved me. And I was polite about it. But I knew that soon enough they would turn their backs and talk about bombing Abkhazia. The war is still here. That is why every Abkhazian man keeps a gun in his house. We need to be ready.”

The Russians first conquered Abkhazia in 1864, and then over the next century or so they more or less toyed around with the place, first granting the Abkhazians autonomy, then sending in soldiers to snatch power away. In 1937, Joseph Stalin gave Lavrenty Beria, then the first secretary of the Georgian Communist Party, the authority to forcibly resettle Georgians in Abkhazia. Beria was born near Sukhumi but was a member of the Mingrelian ethnic group, most of whom lived in Georgia. He moved thousands of Mingrelians across the border into Gali, Abkhazia’s southernmost district. Abkhaz-language schools and newspapers there were shut down. After the Soviet Union broke up, the ethnic Abkhazians eagerly kicked these newcomers out, using Russian weapons.

When Abkhazia declared independence, Russia did not immediately give it diplomatic recognition. That came on August 26, 2008 — four days after Russia finished thrashing the Georgian army in another disputed Caucasian territory, South Ossetia. Russian aid to Abkhazia was also virtually nonexistent before 2008.

“Nobody here calls it a Russian occupation,” Liana Kvarchelia, the deputy director of the Sukhumi-based Center for Humanitarian Programs, said in an email. “That’s a myth promoted by Georgia and Western media. However that does not mean that Abkhazians are unconcerned over their growing dependence on Russia. Various political groups here raise the issue of investing more in local economic development, rather than in patching up holes in social security policies, or in purely infrastructural projects. As for security vis-a-vis Georgia, I think people appreciate Russia’s support, considering what happened in 1992 and more recently in 2008, and also given the fact that Georgia refuses to sign with Abkhazia a non-aggression pact.”

In Russia, Abkhazia is almost unknown. “Asking the average Russian about Abkhazia is about like asking someone in northern Arkansas, ‘What do you know about Haiti?’ ” said Alexei Kuzmin. “They can tell you next to nothing.” When Abkhazia makes a rare appearance in the Russian news, the topic is usually property rights. In recent years, Russians looking for cheap real estate on the Black Sea have been buying up the homes of the exiled Mingrelians.

Nikolai Silaev, a senior research associate at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, views Russia’s presence as a straightforward benefit to Abkhazia. “What about Russia’s presence have the Abkhazians tired of?” he asked. “The guarantee of security? The financial assistance?”

What Russia can’t give Abkhazia is recognition from Georgia — or even assurances of lasting peace. The 2008 flare-up began when Abkhazian troops took over the Kodori Valley, the last piece of Georgian-controlled Abkhazia, only to find that the Georgian troops there had been supplied with U.S.-made weapons.

Georgians regard Abkhazia as a stolen paradise. Kety Mateshvili, an employee of a Tbilisi-based oil company, woefully recalled childhood vacations to her family’s Abkhazian beach home. “It was a magical place,” she said. “We took the overnight train there, and when I saw the sea and the outdoor cafes and the streets lined with palm trees, I was so happy. Now Abkhazia is just a colony of Russia — the Russians tell the Abkhazians what to think and they believe it.”

Maka Tokhishvili, a university student in Tbilisi, added, “Abkhazia is Georgia! Indigenous Abkhazians recognize this territory as Georgia, but they are afraid of Russians and can’t voice their opinion.”

Despite the mass migration after 1992, there are still around 50,000 Mingrelians in Abkhazia. Nearly all are refugees who fled to Georgia during the war, then returned, five or six years later, to reinhabit their homes in Gali, one of the poorest of Abkhazia’s seven districts. (Mingrelians have trouble getting Abkhaz passports, which makes it nearly impossible to get a job.) Today, just as the Abkhazians are ignored by the world, the Mingrelians are often ignored by the Abkhazian government.

In 2011, Human Rights Watch published a report that depicted Gali’s refugees as an abused people “hostage to nearly two decades of political conflict.” The report alleges that the Georgian language is discouraged in schools, quoting one student: “We learn Georgian poems and sing Georgian songs, but if somebody from the town [administration] came, we don’t do any of that. The teachers also ask us not to say anything about it, they are afraid that they could get fired.”

Gali is about an hour southeast of Sukhumi, and the easiest way to travel there is in a marshrutka, or multipassenger minibus. Near the district’s one city (also called Gali), there are defunct tea plantations and, to the southeast, the concrete ruins of a shuttered Soviet-era prison camp. Many of the locals clatter along the road in horse-drawn carts.

At a swimming hole on a river a few miles east of Gali city, a tall and muscular youth dove off a high rock, shirtless in wet blue jeans. Giorgi Kvarackhelia was recently fired from his job at a car wash in downtown Gali, he said, because he didn’t have a birth certificate.

He was born during the war, and as a child he lived in Georgia. His parents, Mingrelians, took refuge there from the devastation surrounding their home in Gali. He once had a Georgian birth certificate, but he doesn’t know where it is; his parents died in the decade following the war. Tuberculosis took his father when Kvarackhelia was five; his mother succumbed to cancer four years later. The young man related all this very quietly.

His sister is also dead, he said. “Our neighbor raped her and killed her and dumped her somewhere. She was seven years old.” Kvarackhelia looked up at his audience, then continued, determined not to sound hopeless. “But the police caught the neighbor,” he said. “They put tires on him, and then they burned the tires and killed him.”

He didn’t go to school. There was no one to take him. As a teenager, he would often hike over illegal paths to Zugdidi, Georgia, a city of 75,000 people about fifteen miles away. “I had friends there,” he said.

Kvarackhelia’s arms are a welter of shiny pink razor-blade scars. Above one wrist, he has a fading tattoo — a squiggly dull-black drawing of a knife. When he was thirteen, he said, he stabbed a Georgian border guard in Zugdidi. He did not elaborate, except to say that he had spent six years in a Georgian prison for the crime. “The guards beat me every day,” he said. “They do that if you hurt a policeman. But if you cut yourself, they leave you alone.”

Behind bars, Kvarackhelia struck up a telephone romance with a girl. He saw her for the first time when he got out last summer, and they married at once. The girl was waiting by the river — sixteen years old, slight, and meek and withdrawn.

“What next?”

“I want to get a job,” Kvarackhelia said, “but my bicycle is broken, and the bus runs to town only three days a week.” He shrugged, and then he looked down again, blinking.

It’s a twenty-minute drive on a flat and absurdly bumpy road (unrepaired since the war) from Gali to the village of Sida. In the village, a heavyset woman with gaps in her graying teeth leaned against her front fence and said, “It is miserable here. We don’t have any options. Otherwise, we would leave.” Ineza Parulava is fifty-four. Before the war, she picked tea for money. Now she lives with her elderly mother, earning a living by raising a few cows. A brown-and-white calf, still spindly-legged, wandered around on her lawn. She said, “The electricity goes on and off. There are criminal gangs on the border near Gali city, and the roads are bad.”

Like many Mingrelians in Abkhazia, Parulava gets a small monthly check from the Georgian government. Hers is for fourteen dollars. She travels to Zugdidi a few times a year to get the money.

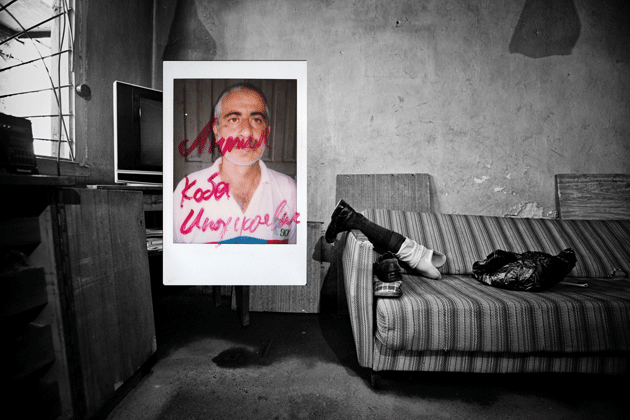

Back in Gali, another Mingrelian, forty-six-year-old Antia Koba, had nothing bad to say about the Abkhaz government, but he’s haunted by the war nonetheless. “When the war started, the Georgians kept coming after me,” he said. “They wanted me to fight on their side, and I told them, ‘No, I don’t want to turn the Abkhazians into corpses. They are my brothers.’ I escaped from here. I went to Zugdidi, and there it was worse. There was nothing to eat.” Every few days, Koba came home to Gali, running through forests and fields, to find food. “I must have run along the same path fifty times,” he said, “but one day I stepped on a land mine and it exploded and I just jumped in the river, screaming.”

Koba underwent two surgeries in Russia, but the mine’s damage was irreversible — after eight months of rehab, his leg was amputated at the knee. He rolled up his trouser leg and detached his prosthetic, exposing the stump. “I don’t know who put the mine there, the Abkhazians or the Georgians,” he said. “I don’t know. I had just finished university. I was starting my life, and now I have nothing.”

Koba is unemployed and lives alone. Two of his neighbors, older men in faded sun hats, were slumped on a wooden bench nearby, waiting. There was a large bottle of chacha, or homemade vodka, sitting beside them, and the moment the interview was over Koba reached for the bottle and drank a glass, smacking his lips when they burned. He poured himself another glass, and then another, and in time his solemn fright dissolved and he was out on the lawn, joking around with his neighbors.

“Oh, come on — they’re Mingrelians,” Basaria, the interpreter, said when she learned about Antia Koba, the amputee, and Giorgi Kvarackhelia, the lost swimmer. “They’ll tell you anything.”

Liana Kvarchelia emphasized that poverty and violence affected both sides of the ethnic divide. “But Gali is missing from our TV reports and our newspapers,” she said. “The Abkhazian media sees the people in the Gali district as animals, and our journalists go there only when there is fighting between us and the Georgians.”

Abkhazian nationalism is largely undiluted, and it shows up in odd places — at the gaming table, for instance. The country is competitive on the world dominos circuit. In Sukhumi, you can see people playing at outdoor tables at all hours. At the 2013 world championship in Orlando, Florida, a young Abkhazian economist, Almas Gabunia, placed eleventh in the open division. The Abkhazian team was fourteenth overall, out of eighty-eight.

The Abkhazians’ coach is Almas’s father, Artur Gabunia, a balding and meditative man with a broad forehead and expressive salt-and-pepper eyebrows. Over coffee, he reminisced fondly about the 2011 world championship, which was held in Sukhumi. “Georgia wrote a letter to the International Domino Federation, saying that the venue should be moved,” Gabunia said. “Then the federation voted and decided, ‘Yes, let’s do it in Abkhazia.’ The Georgians didn’t come.”

The 2013 championship brought Abkhazia more luck: in the ballroom of the Florida Hotel, in Orlando, the flags from all eighteen visiting countries were arranged, fortuitously, in alphabetical order. “Our flag was first,” Gabunia said. “It was a golden moment. Everyone on our team knew that blood had been shed for that flag. And we got to tell the world about our little country.”

Georgia was not at the 2013 championship either. So one wonders: What would happen if the two nations faced off?

“I can’t say,” Gabunia said, “but we play a pretty hard game.”

At the Abkhazian State Museum, in Sukhumi, a war veteran — a Jordanian émigré named Khaldoun Leiba — helped to curate a permanent exhibit, “Our National War,” which chronicles the 1992–93 conflict, tracing its roots back to the nineteenth century. Leiba is fifty-two, and slim, with curly silver hair and a jaunty mien. He served in the army during the war, and now at the museum he moved through the corridors nimbly, in pointy black dress shoes, flirting in Russian with the female staff. “Smeshnoi!” said one woman amid peals of laughter. “You are so funny!”

Discussing the war, Leiba spoke gruffly, in English. “This is our land,” he said. “We kicked the Georgians out. We attacked them from the sea, from the mountains. Too many bullets! We won! When you are right, God is with you.” He climbed some stairs into a hallway, a cluttered staging area for the exhibit. On the floor there was a phone book–size chunk of dull-gray crumpled aluminum with rivets in it. This, Leiba said, is scrap from a helicopter the Georgians downed near the mountain village of Lata, killing eighty-six Abkhaz civilians. Nearby is a tarnished, oversize bust of Stalin. “That guy,” Leiba remarked, “he was — how do you say it? He was an asshole, a douchebag.”

The museum’s graying, middle-aged director, Arkadi Dzhopua, confirmed that the exhibit would be critical of Georgia. “We will have the little toys of the children who died,” he said, leaning back in his chair, in a cramped office on the top floor of the museum. “It is difficult to show these things, but we have to: this was a war of a large nation against a small one, like Americans fighting the Indians.”

Dzhopua revealed that he, too, fought in the war against Georgia. Then he leaned over his desk and, in an angry whisper, added, “In the war, we were just trying to keep the land that has always been ours — that is all we were doing. That is the message of this exhibit. And if Georgians come here to the museum, I hope they will learn that the war was their fault. They should feel sorry for everything — sorry to God and sorry to Abkhazia.”

A mile away, behind the concrete walls and the razor wire at their new barracks in Sukhumi, Russia’s soldiers slept. Downstairs at the museum, the bust of Stalin sat in darkness, gazing at the wreckage scattered in the hallway.