My father always stressed the importance of blood — being worthy of it, showing loyalty to it, protecting what he called the purity of it. He was, as people sometimes say of well-educated racists, not a stupid man. He had a master’s degree in aerospace engineering, and he was valedictorian of his law-school class. But he considered slavery a benevolent institution that should never have been disbanded, and he viewed his and my fair skin as a mark of superiority.

The world being what it was in my post–civil rights era youth, he had retreated to an ardent, evangelical separatism. “Birds of a feather flock together,” he was fond of saying. He said it at the breakfast table; he said it on the way to the pool; he said it while covering the faces of brown children in my storybooks with my mother’s nail polish. Sometimes he closed the pages before the polish dried, so they stuck together, leaving nursery rhymes unrhyming and stories filled with gaps. He often recounted his triumph over being assigned, as an undergrad, an Asian-American roommate: “I marched right over to the housing office and told them I wasn’t going to live with a Chinese.”

The Family Photograph Tree, a lithograph published by Currier & Ives, c. 1871. Courtesy the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

I remember being eight or nine, traipsing around some godforsaken family parcel in the Mississippi Delta, dried-out cotton boll in one hand, burlap sack filled with more in the other, my younger sister trailing behind, as our father tried to impress on us the momentousness and immediacy of various Civil War battles. Our forebears had been killed on or near that very land, I recall his saying. Mostly I remember wanting to go home to my mother in Miami. She had opted out of this trip, as she often did toward the end of my parents’ marriage, and I consoled myself by imagining her contempt.

The first time I saw a family tree, a year or two later, my father carried it into my bedroom with tears in his eyes to explain why he and my mother should not and could not divorce. Flicking through pages of unfamiliar names, he explained that nowhere in our branch of his mother’s mother’s tree, all the way back to a Revolutionary War lieutenant born in Virginia in 1755, had anyone ever divorced. It would be a terrible scandal and would bring ignominy on his grandmother’s line and on our family — on our blood, he probably said — if he and my mother were to become the first.

I’d never seen him cry before. Though I was always pleading with my mother to leave him, I cried, too.

I never expected to become interested in genealogy. When I did, slowly at first and then in great gusts of extreme obsession, I thought I owed the fascination to my mom, a natural storyteller descended from a collection of idiosyncratic Texans. One of her granddads was a strident Dallas socialist; the other killed a man with a hay hook. Her father, Robert Bruce, is said to have been married thirteen times to twelve women. I figured this must be an exaggeration, but so far I’ve tracked down records of six wives, and his relationships tended to be short-lived — one wife shot him in the stomach just a few weeks after their wedding — so it seems plausible that there were unions I haven’t yet found.

I didn’t associate my mother’s stories with genealogy — didn’t see any real kinship between them and that packet of papers my father shared with me — until the day I idly typed my maternal grandmother’s name, Alma Kinchen, into Google. An old New England tree, stretching back to Cornet Joseph Parsons and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, came right up. Until then, I’d believed all my colonial ancestors, on both sides, were Southern.

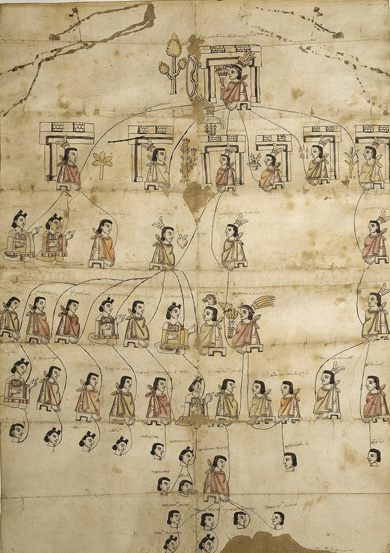

Aztec genealogical tree, c. 1600, from Tlaxcala, in current-day Mexico © bpk, Berlin/Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen, Berlin/Dietrich Graf/Art Resource, New York City

Parsons, apparently my ninth great-grandfather, co-founded the town of Northampton, Massachusetts. His wife (and my ninth great-grandmother), Mary Bliss Parsons, was accused of being a witch there but beat the charges. According to the authors of Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England, Parsons was said to converse with spirits. She was also the foremother of a couple of female preachers in my maternal family line. This intrigued me, because eleven generations later, rather suddenly, my mom had found God and started casting out demons and reporting visitations from angels. She’d run a church out of our living room, attracting up to fifty down-on-their-luck worshippers to our house every week. (When my father did eventually file for divorce, it was because my mother refused to disband her congregation.) My mother didn’t know about her ancestors’ churches when she started hers.

A few years before I discovered our connection to the place, my sister moved to Northampton, to a house just blocks from the plot where the Parsonses once lived. Every time I visited her there, I felt (or at least, in the fate-infused view of history so prevalent among ancestry buffs, now told myself I had felt) a surprising sense of belonging.

Genealogy is an ancient human preoccupation. The God of Hebrew Scripture promised Abraham descendants beyond number, like the stars in the sky and the sand on the seashore. The apostles Matthew and Luke claim that Abraham’s lineage went on to include King David and eventually Jesus, though the specifics of their accounts are contradictory after David. Muslims trace Mohammed’s line back through Abraham, to Adam and Eve.

Using genealogy to connect humans to the divine is not unique to the Abrahamic faiths, of course. In the legends of Ancient Greece, gods and mortals consort freely, their unions giving rise to the demigods whose origins Hesiod charted in his Theogony. Egyptians thought their pharaohs to be divine, and could trace them to Narmer, the first king of unified Egypt, who lived around 3150 b.c. The family tree for Confucius, who advocated ancestor worship, stretched back more than 2,500 years.

Originally, the practice of recording family history on any sustained scale was, as François Weil writes in his excellent, long-overdue survey, Family Trees: A History of Genealogy in America, “the prerogative of kings and princes” and, later, high nobility. Only in the late fifteenth century did bourgeois European merchants start emulating aristocrats and creating their own records. Even then, according to Weil, the practice was imported to the New World only piecemeal. Some early colonists used Bibles to record births, deaths, and marriages, but “ascending,” or backward-looking, genealogies became common only after 1750.

In the nineteenth century, Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose great-great-grandfather presided over the Salem witch trials, explored his ambivalence about the Puritans in his fiction. Ralph Waldo Emerson compared talking with a genealogist to sitting with a corpse, but also praised the “kind Aunt” who told him about his ancestors. And Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who like many at the end of the nineteenth century fetishized what Weil calls “Anglo-Saxon purity,” touted her “extremely remote connection with English royalty” in her autobiography.

Following the Civil War, questions of family history were immediate and urgent for freed slaves. Many who had been separated from children, parents, and other loved ones wrote to the Freedmen’s Bureau, ran ads, enlisted the help of churches, and searched in person. Meanwhile, white Americans who wished to “own a pedigree” began hiring professionals to do the work for them. The idea of genealogy as a science had not yet taken hold, and inept and unscrupulous practitioners of the art flourished. Mark Twain’s 1892 novel The American Claimant satirized what a contemporary newspaper called “unclaimed-estate fever.”

Only in the twentieth century did genealogists begin to insist on archival evidence. Slowly, writes Weil, “a democratic interest in family history replaced the previously dominant elitist quest.” In the late 1970s, Alex Haley’s Roots inspired ordinary people of all ethnicities and backgrounds to learn about their forebears. With the rise of research sites like Ancestry.com, which sold for $1.6 billion in 2012, genealogy has become a formidable industry.

In the past, researching my family would have entailed visiting government offices, digging around in musty archives, and corresponding by post with strangers hundreds or thousands of miles away; as it was, I started with an account on Ancestry.com. There I created my own tree, which tied in to other people’s trees, and began the long, still-unfinished work of trying to verify their research while adding my own, mostly with the help of other electronic databases. Back when I joined, in 2007, the site had a highly dubious (and now discontinued) Find Famous Relatives feature, which suggested I could be related — incredibly remotely — to William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Audrey Hepburn, Mark Twain, Gore Vidal, and the Mayflower passenger Edward Tilley. From the start I saw how manipulative this tool was, and how unreliable. It hooked me anyway.

So many of the best American family histories — Annette Gordon-Reed’s The Hemingses of Monticello (2008), William Keepers Maxwell’s Ancestors (1971), Joan Didion’s Where I Was From (2003), Joe Mozingo’s The Fiddler on Pantico Run (2012) — rely on research, on census data, deeds, wills, diaries, and other such documents, and on stories passed through the generations. No matter how canny the researcher, though, or how long-standing the pedigree, stories can be wrong and documentation false.

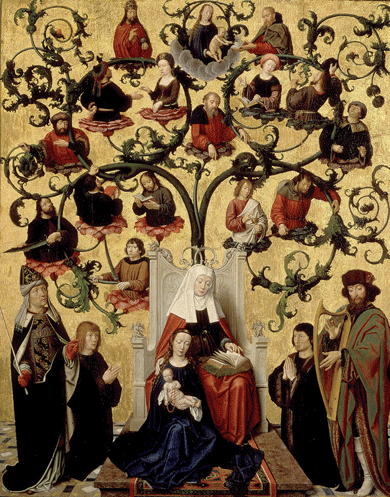

The Genealogy of the Virgin Mary, by Gerard David © Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, New York City

For about a hundred dollars, it is now possible to spit into a tube, drop it in the mail, and within a couple of months gain access to a list of likely relatives. If you have any colonial American ancestors, the first thing you realize, taking a DNA test for genealogical purposes, is that potential sixth cousins are a whole lot easier to come by than you ever imagined. Even fifth cousins — people with whom you share a fourth great-grandparent — aren’t a particular scarcity. On 23andMe, the largest autosomal-DNA-testing site, I have more than 1,400 predicted relatives. On Ancestry.com, I have more than 10,000 possible matches. Apart from my mother, my two closest matches on 23andMe share 1.26 percent and 1.23 percent of my genome. They haven’t responded to my requests to share information — many people don’t — but in both cases we might be second or third cousins.

With the rise of these tests, secret forefathers can be uncovered and prestigious lineages invalidated in an instant. A new world has opened up, for adoptees, African Americans, the descendants of Holocaust survivors, and anyone else cut off from her origins.

For now, unless they get very lucky, people seeking to unravel their ancestry can spend a very long time, often years, closely examining DNA matches, identifying multiple third and fourth cousins whose genomic segments overlap not just with the seeker’s but with one another’s, emailing those people, enlisting help from their relatives, and in some cases working with professional genetics researchers.

CeCe Moore, the most interesting and intuitive genetic-genealogy consultant I’ve encountered in my wanderings through this world, points out that although autosomal-DNA tests can pinpoint the genetic truth of relationships, “people with a storied pedigree have a lot to lose” and often refuse to risk being tested. Moore’s own brother-in-law discovered in 2011 that Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings are his fourth great-grandparents. While DNA results show “tons” of Jefferson descendants and the evidence that Hemings and Jefferson had children together is overwhelming, Moore can’t write about her brother-in-law’s discovery “officially, scientifically” without DNA data from the “pedigreed ancestors,” and “it’s difficult to get them to test,” she says.

Moore sees a kinship between what she does and detective work. Like so many people who are drawn to genealogy, she’s fascinated by uncanny coincidences. The first time her sister’s family visited Jefferson’s home in Monticello, before they knew of their connection to the man and the place, her niece fainted. It could have been the warm day, Moore concedes, but her niece had never fainted before, and never has since.

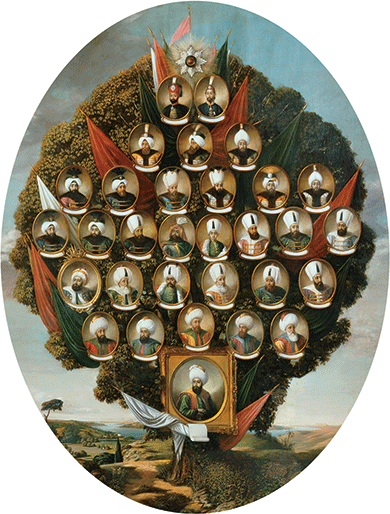

Genealogical tree of the Ottoman sultans, 1866–67, during the reign of Abdülaziz © Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, New York City

When we spoke, Moore was researching Henry Louis Gates’s ancestry for the next season of his PBS show, Finding Your Roots. Gates and his genealogy team produce watchable and often profound television. In one moving episode, Georgia congressman John Lewis, who marched for voting rights with Martin Luther King Jr., weeps when he learns that some of his ancestors freed after the Civil War were among the first black people to register to vote in Georgia — before their right to do so was rescinded. It’s hard — for me, at least — not to see these kinds of echoes as fated.

The ultimate goal of DNA-based genealogy is to create a “Universal Genetic Family Tree” revealing exactly how everyone in the world is related. Moore calls the universal tree an “inevitability.” A genomic database of this kind would eliminate false pedigrees and solve long-standing ancestral mysteries. What it would mean for humankind beyond that is hard to say. I’m incredibly nervous about it. If each of us were as readily identifiable from our saliva as the characters in Gattaca are from their skin cells, to what ends might this information be used? My anxiety about the implications of DNA-based genealogy has not prevented me from being tested at both 23andMe and Ancestry.com, though, or from uploading my raw data from each of those tests to GEDmatch, a site about which I know very little except that it enables cross-platform data-sharing. My fear and my curiosity battled it out, and my curiosity won. It wasn’t much of a contest, honestly.

From the start of my ancestry research, there was a defiant aspect to my truth-seeking: Okay, we’re talking about blood, we’re supposed to pledge allegiance to blood, but what does that mean, exactly? My father and his parents were delighted to tell you about my grandma’s pre-revolutionary Bailey ancestry, and our connection, by marriage, to the Mannings of football fame, so I was surprised when my mom told me that the Newton family patriarch, her grandfather-in-law, evaded her questions about his lineage. Ordinarily this was a man who liked to hold forth, the sort of guy who told women at a restaurant what they were going to eat and then ordered for them.

Soon I was spending whole weekends mired in the U.S. Census, working backward through history. Eventually I arrived at one Jesse Newton, a farmer born and married in North Carolina in the early 1800s, who later bought land in Drew County, Arkansas, where he served as treasurer and was “granted a license to retail spirituous and vinous liquors.” There he raised his nine children — four daughters and five sons — along with a boy who’d been orphaned at the age of three. According to the “slave schedules” of the 1860 Census, which list the ages and genders but not the names of those enslaved, Newton owned six people. Josiah Hazen Shinn’s Pioneers and Makers of Arkansas (1908) refers to him as “an honored citizen.” While there was plenty about this I would have liked to disavow, if there was something my father’s family wanted to hide, I couldn’t find it; nor could I trace the Newtons any further back.

In 2009 I tracked down my granddad’s cousin Wallace Newton, then eighty-three, to see whether he could verify that Jesse Newton was in fact my fourth and his second great-grandfather. He could not. “We had the same problem that you had,” he told me. “We just could not get anyone to give us information.” His daughter theorized that we might be related to the Newton Boys, the notorious early-twentieth-century bank robbers, which would have delighted me. But while that family was descended from a Jesse Newton of Arkansas, and I’m increasingly convinced ours was, too, these are two different men. I haven’t found a tie between our lines, just proximity and similar names.

I suppose I was hoping for some refutatory reveal. Having failed to find one the traditional way, I turned to DNA. What would my genome reveal about my father, the 5'7½" amateur eugenicist who’d bequeathed to me his poor eyesight; his unimpressive stature; his awkward, clipped way of walking; and his near-homicidal intolerance of many common noises? He’d married my mother because he’d thought they would have smart children together, and in the ensuing years he’d catalogued my many shortcomings — from lackluster math skills to a thyroid condition — and accused her of failing to warn him about her “defective genes.”

According to 23andMe, my mother is 99.9 percent European, with a tiny bit of Oceanian ancestry, and I am 99.7 percent European, 0.1 percent North African, and 0.2 percent some other, presently unclassified thing. My North African and unclassified genes must have come from my father, an irony I somehow doubt he would allow himself to enjoy. The discovery that I am almost exactly as white as I have always appeared was deeply, irrationally disappointing, as though having greater mixed ancestry would somehow have mitigated the wrongs of my forebears. Many people have the opposite response. The white supremacist Craig Cobb, who sought to establish an all-white town in North Dakota in 2012, took a DNA test to establish the purity of his bloodline and discovered on live television that his genome is in fact 14 percent sub-Saharan African, a larger percentage than a person would ordinarily share with a great-grandparent. “Statistical noise,” he called the result. Later he announced plans to be retested. “I had no idea, or I wouldn’t have gone and done that, and I still don’t believe it,” he said.

So genealogy may be a big-tent hobby, but its practitioners congregate uneasily together. In the 23andMe forums, a subscriber reported that one of her partner’s DNA matches rejected a request to share information with the following note: “There has just got to be something wrong with Relative Finder. I can’t be related to either you or your ‘friend’ — we just don’t have BROWN people in our family.” Andrea Badger, one of the site’s “ancestry ambassadors,” reported in the comments that another user had encountered a similar situation when one of his matches “thought he was Jewish and sent a message full of racial slurs.” Elsewhere on the site, a user with the screen name RyanMD started a contentious thread entitled “Are Ashkenazi Jews and other ethnic groups really smarter than others?”

The writer and Los Angeles Times reporter Joe Mozingo discovered, while researching his own heritage, that his last name is not, as his family had always said, Italian, but one of two African surnames known to have survived slavery. In The Fiddler on Pantico Run, he describes encounters with distant cousins who refuse to accept the overwhelming evidence he shows them. Even among close family members who profess to find the story fascinating, he told me, he detected an “undercurrent of resistance to the idea” that their name came from Africa.

In my research, I’ve identified common ancestors with only a handful of matches, all of them predominantly European. One remembers visiting my second great-grandmother’s house in the Mississippi Delta; another says that a fourth great-grandmother on my mother’s side lived in poverty but “kept her bed with the featherbed squared off and covered in beautiful linens.” Looking at photos of Kristin Gossett (née Arnos), a third cousin twice removed on my dad’s mother’s side, I see echoes of my first cousin’s smile. Kevin Kinchen, an Ancestry.com DNA match who’s probably my fifth cousin on my mom’s mother’s side, has a background in pattern recognition, private investigation, and forensics. He calls genealogy “the ultimate puzzle box.” It never has to have an end, he says.

Although I’m mostly European and most of my matches are, too, some are not. It’s impossible to estimate what percentage of my predicted cousins are of predominantly African ancestry, because 23andMe only allows me to see the information each match permits, but as is the case with many if not most descendants of slaveholders — and I descend from a few — that percentage is far from nominal. Slavery did so much to erase records of the personhood of its victims that, so far, I haven’t been able to identify a precise common ancestor with a single African-American match.

Matthew Ware, one of my predicted third to sixth cousins, is a physics professor at Grambling State University. 23andMe breaks his genome down by region to 53 percent European ancestry, 43.6 percent sub-Saharan ancestry, 0.5 percent East Asian or Native American, and 2.9 percent unassigned. At first, engaging in the sort of quasi-magical associative thinking people often tend toward where DNA and ancestry are involved, I assumed he was a relative through my father’s side, because of their shared interest in science, a common connection to Mississippi, and even, I thought, Ware’s physical resemblance to my father himself. In fact, though, he matches me through my mother. He’s learned that he’s descended from a Revolutionary War hero, a former slave, and an exiled Scottish rebel.

Another possible third to sixth cousin, Deborah Hampton-Miller, is a writer working on her second book. “I believe that gift runs in the family (bloodline),” she told me in an email. Hampton-Miller is of predominantly sub-Saharan ancestry (77 percent, plus 16.6 percent European, 2.3 percent East Asian, and 1.8 percent Native American). Because she doesn’t share genes with my mom, we must be related through my dad. So far we haven’t been able to link up our trees.

The percentage breakdowns given on sites like 23andMe cover only the past 500 or so years, offering a very limited glimpse of users’ historical interconnectedness. Ultimately, of course, we’re all related — our first ancestors all originated in the same place. Henry Louis Gates has argued that genealogy and genetics research will “revolutionize our understanding of American history and also our concept of race” in ways that were previously impossible. The revolution begins, Gates contends, “when we realize there is no purity.” Having been raised by a devout racist, I would like to share Gates’s optimism, but I feel at least as much fear about the outcome of these tests as I feel hope.

A century ago, the possibility of improving the human gene pool was widely accepted as a science. Today we tend to associate eugenics with Nazism, but its proponents weren’t all right-wing fascists. George Bernard Shaw advocated “the socialisation of the selective breeding of Man.” Bertrand Russell proposed color-coded “procreation tickets” and fines for mismatched ticketholders who dared to have children. “Three generations of imbeciles are enough,” wrote the esteemed Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in Buck v. Bell, a 1927 decision upholding Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Act of 1924, which was targeted at “mental defectives.” I first learned of this case in my early teens, because of my father’s enthusiasm for Holmes’s opinion. For a while after my parents’ divorce, my father took my sister and me to lunch at the same fast-food restaurant every Sunday at a time when an elderly woman and her disabled son would be eating there. Every week, throughout these meals, my father muttered about imbeciles as the man shakily tried to feed himself.

Twentieth-century proponents of eugenics advanced it as a remedy for a wide variety of perceived heritable shortcomings, including lack of intelligence, as defined by the eugenicists themselves. In a letter to the Scottish Herald in 2006, the author Richard Dawkins wondered, “if you can breed cattle for milk yield, horses for running speed, and dogs for herding skill, why on Earth should it be impossible to breed humans for mathematical, musical or athletic ability?” Although he did stop short of actually advocating for the creation of “designer babies,” he argued that “60 years after Hitler’s death, we might at least venture to ask what the moral difference is between breeding for musical ability and forcing a child to take music lessons.”

Until the U.S. Food and Drug Administration ordered 23andMe to stop providing health data late last year, the company routinely ran tests for a number of genetic indicators that are at the cutting edge of preventive research — whether you’re a carrier for common strains of cystic fibrosis, whether you’re at increased risk for Alzheimer’s, how likely you are to contract tuberculosis if exposed. The site predicted fertility, longevity, skin pigmentation, and likely allergies, and it also purported, somewhat tentatively, to answer more speculative questions. Is your episodic memory “increased” or merely “typical”? Can you effectively learn to avoid errors? Do you have a high or only average nonverbal I.Q.?

In September, the site received a patent for its Inheritance Calculator, which so far is fairly limited. It tells me, for example, that if my husband (who has also been tested) and I had children, their genes would predispose them to being able to perceive bitter tastes, to tolerating lactose, to being sprinters rather than endurance athletes, and to having brown or black eyes. Presumably 23andMe, if allowed to resume business as usual, would widen the scope of this data.

In the site’s forums, subscribers discuss their results and pore over studies reported in the media. The “empathy gene,” though not incorporated into 23andMe’s own testing, has been a popular topic on the site since reports of it emerged in 2009. Although I have this marker (GG at Rs53576), I relate to the description of its typical expression only partly; my empathy tends to be as free-floating as my anxiety, which is saying something.

Though I possess only half the personality traits ostensibly connected to the “empathy” genotype, I often find myself effectively taking its supposed import at face value. As I suspected, my mom, who was recently tested, is also GG. My father — well, I would guess — is not. Yet each of my parents contributed one of my Gs. Scientifically speaking, if this study has any validity, each is half responsible for passing along whatever heritable capacity for empathy I do or do not have.

In her 2011 book, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, Amy Chua argues that the academic success of Chinese-American children stems from the cultural practice of forcing them to study and demanding that they be the smartest in every class. She attempts to ward off accusations of racism by saying that she knows “Korean, Indian, Jamaican, Irish, and Ghanaian parents” who qualify as “Chinese mothers.” I would like to nominate my father for membership.

Chua’s new book, The Triple Package, written with her husband, Jed Rubenfeld, contends that all successful groups in this country — immigrant, cultural, and religious — possess the same three traits: a sense of insecurity, a sense of superiority, and strong impulse control. Tracing the cultural rise and fall of American Protestants, emphasizing the success of Asian, Jewish, Indian, Cuban, and Nigerian immigrants, and of Mormons, Chua and Rubenfeld’s arguments waver on whether particular traits are endemic to certain ethnic groups, but they attempt a shaky landing on the side of nurture, of learning. The triple package can be inculcated, they say; it can be and is taught. Although the book is ostensibly intended to repudiate the notion of innate characteristics, as I read it I kept thinking of DNA testing, which seems to want to tell us what our genomes predestine us to be.

Eugenicists find their justification in Darwin, but the Darwinian truth is that the fitness of traits is entirely contingent on environment. A “defect” in one context is a strength in another. Heavily pigmented skin is an evolutionary advantage in equatorial climates and a disadvantage in frigid zones, because it produces less vitamin D. Perhaps a lack of empathy would have been advantageous to a slaveholder; whether it is desirable in any era is another matter. If it were proved that impulse control and feelings of insecurity and superiority served children well in the twenty-first-century United States, we could not predict their value for all times and places. Even Chua herself (obviously in ample possession of these traits) admits, following what a New York Times Magazine profile calls “a showdown in a Russian restaurant (yelling, smashed glass),” that she “pushed her younger daughter too hard.”

Ancestry is a fundamental perplexity of life. We come from our parents, who came from their parents, who descended, as the Bible would put it, from their fathers and their fathers’ fathers, but we are separate beings. We begin with the sperm of one man and the egg of one woman, and then we enter the world and we become ourselves.

Beyond all that’s encoded in our twenty-three pairs of chromosomes — our hair, eyes, and skin of a certain shade, our frame and stature, our sensitivity to bitter tastes — we are bundles of opinions and ambitions, of shortcomings and talents. The alchemy between our genes and our individuality is a mystery we keep trying to solve.

At times my own research has felt like a sickness, as though, if I dug deeply enough, if I scrutinized my findings hard enough and long enough, I might understand why my mother became a preacher and I became a writer and my father was unable to love me in a normal fatherly way. My guess now is that my Newtons were so cagey about their background not because they actually had anything to hide but because they feared their ancestor might be mistaken for someone disreputable.

But this is only a hypothesis. The branches of my tree — of all our trees — widen back inconceivably until, finally, they meet up with everyone else’s. The puzzle of who we are, whether we are shaped more by our genes or our environment, is a philosophical finger trap from which humankind cannot escape.