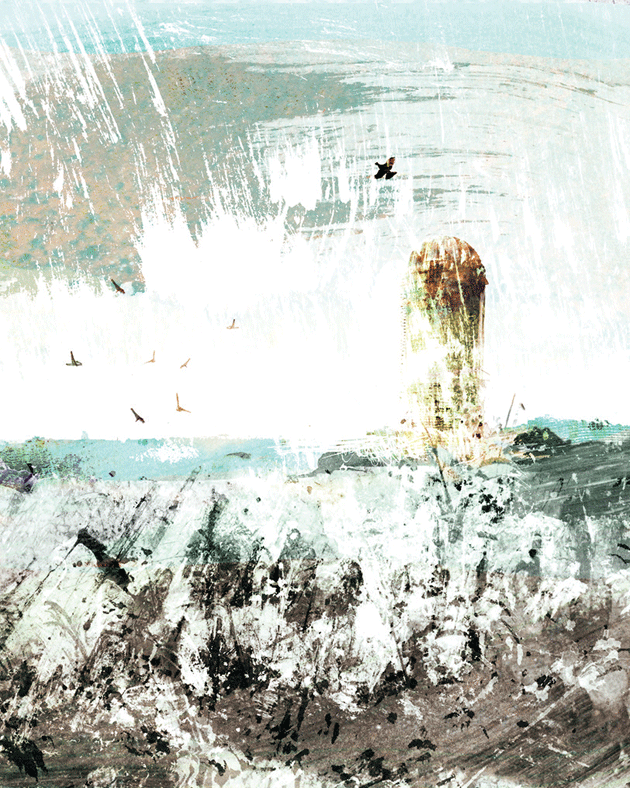

It was February and the rungs were cold as rods of ice. Beneath the suit he’d never had the occasion to get married in, Ernie Boettner was wearing his favorite flannel long underwear, the red sleeves of which stuck out past the cuffs. Despite the extra layer, he was still underdressed for climbing a silo in February in Illinois. He told himself that his senses had begun not to matter, but his teeth were chattering. He couldn’t tell whether he was breathless from the cold or from the climb or both. Fifteen feet off the ground the ladder was encircled by a safety cage that continued all the way to the top. When he reached the cage, Ernie leaned back and felt the freezing metal through his clothing. He closed his eyes for a moment, then looked up and kept climbing.

There had always been rumors about Ernie Boettner and Chester Bradbury. The milkman talked of seeing Chester’s veterinary truck sitting in the barnyard some mornings when he came to pick up the milk, but he’d heard that Ernie had trouble keeping his herd healthy — a rumor that Ernie himself had sown — so there was a good explanation as to why the veterinarian spent so much time over there. Luckily the homophobia of Pearl County was subtle, if only because it had so little occasion to manifest itself. In general, men saw what they wanted to see and ignored what they did not, including Brokeback Mountain.

Chester was already undergoing his second round of chemo when the movie came to the Pearl Theater. Ernie saw it five times, careful to disguise himself. He wore varying combinations of two pairs of glasses and three hats. In the end, these precautions were probably unnecessary. The stoned boy selling tickets hardly glanced at the customers, lost as he was in a reverie of his future life in Hollywood. And Ernie made sure to show up late, when the theater was already dark and the previews were rolling. He sat in the back row, and after the first time, he would leave while Ennis was still touching the bloody fabric of Jack’s shirt. He would slip out through the side exit and walk briskly to his truck, his chapped hands in his pockets, crying because of what the movie had clarified in his life and vice versa. Then he would drive to the hospital.

Still, he couldn’t help but feel that the guys down at the Bluebird Diner and at Morton Saint’s Tap knew he’d seen the movie five times. That winter, Brokeback Mountain was practically all they talked about, which was interesting since none of them had seen it. They claimed they never would, though it was pretty clear to Ernie that once it came out on DVD they’d watch it one way or another, even if they had to drive a few counties away and open an account at a distant Blockbuster so they could rent it in anonymity. A few of the guys had written letters to the local newspaper complaining that the movie had been shown within the city limits. There was even talk of boycotting the theater, but that fell silent when the next big movie came through.

In the midst of all this, Chester was dying in Pearl County Memorial Hospital. When Ernie got to his room, he would find Chester propped up against the pillows, reading a James Herriot book. Ernie would pull the curtains around the bed and sit down to tell him the story of the movie again. His telling varied slightly each time, but the end was always the same. He’d changed the original so that the two men lived happily together on the Twist family ranch, whipping the place into shape. They ran cattle and fixed up the buildings and made a living of it. In the last scene, Ennis and Jack lay in each other’s arms against a couple of hay bales, gazing out from the barn loft at a classic western sunset as the camera slid between their heads into the distance. Distilled in the lie was the hopeless hope that this would be their ending as well, that Chester would kick the cancer and the two of them would finally not give a shit anymore what anyone thought and settle down at Ernie’s place to live out their lives together.

On one of Chester’s last days, he sat up in bed when Ernie walked in, and said, “I’ve had a vision of heaven.”

Alarmed at how fast Chester was slipping, Ernie turned to call for the nurse, a tough young farm girl named Amber, but Chester gestured for him to come closer. “Yes, Chester, what’s heaven look like? I’ve always been curious.”

“Heaven’s a tavern. There’s a fire burning no one has to tend to and the beer’s free and you can drink it forever and never get too drunk.”

“Is it like Morton Saint’s, then?”

“Did you hear what I said? There’s a fire and the beer’s free.”

“So it isn’t like Morton Saint’s.”

“No. No, it isn’t like Morton Saint’s at all.”

Chester died on the morning of February 28, 2007. Amber held Ernie while he wept into her shoulder. She said nothing, she just held him. Someone came into the room to do something technical and promptly left. When Ernie had cried himself out, he nodded and without even thanking her (because there was no need), he left as well.

He held himself together at the funeral, enough so that it seemed to everyone present that the two men had been no more than very good friends. This was a relief to many. If Ernie had thrown himself at the coffin, which contained not only Chester’s body but the stethoscope he had used to listen to a thousand bovine hearts, it would have been too much for most of the crowd to handle. He bore the coffin with Chester’s brothers and nephews and cousins (their names and relations to his lover a blur), and when it came time to take up the spade and toss a little soil in, he handled the task like any farmer would: with a practiced skill, as if he were burying a water pipe that had burst and been fixed.

Ernie believed everything Chester said, and that included his vision of heaven. Since the funeral, Ernie had pictured him sitting up there in some celestial tavern, drinking beer and getting just the right buzz off it forever, and good songs were always playing on the jukebox, and whenever any of the dead came up and tried to sit on the stool next to him, Chester would say, “Sorry, saving this one for a friend.”

A year and a day after Chester died, Ernie was halfway up the silo. He tried not to think of himself jumping and falling, but imagined instead the February land rising up to embrace him.

But when he twisted around and peered through the cage and saw how high he already was, he was moved by pity for himself. He saw himself from a distance, a man in a dark suit and hat climbing his own silo, and why? Because he could not grieve openly for the death of his lover. Dying, he figured, was preferable to keeping his grief hidden.

Anyway, there would be no spring that spring. How could there be? The first spring after Chester’s death had been a mistake: the earth hadn’t yet noticed that Chester was buried in it. Everything that blossomed had blossomed stupidly, every bird that sang had sung a stupid, foolish song, both the blossoming and the birdsong like the idiot laughter of children too young to understand they’re at a funeral. But by now the earth had grown wise to this. He could see the snow still in the furrows, and knew no grass would pierce the ground, no birds would return from the warm south. The land would continue to be lorded over by the pigeons, who were, even now, describing invisible circles over the fields, and the crows cawing in the oaks below. The flowers would decline the invitation of the warming air and the rainy earth. It would always look just like it did on this evening.

When he reached the top, there was a balcony, a platform barely larger than a grill. The sides of the ladder curved up and formed a kind of banister around this platform, which led to a little door in the dome-shaped silo. The little door was open. From it exuded the warm, mashy smell of last fall’s corn. He hadn’t wanted to plant it, but did so because he always had. And because he’d planted it, he’d had to harvest it, and now it was all beneath him. Every kernel was vivid to him. He stood there like a king in a tower and gazed out over his kingdom. Then he took a deep breath and looked down at the ground that would rush up and put him to sleep as gently as Chester put things to sleep when this was what had to be done.

Having allowed himself to look down, holding his hat so that it wouldn’t fall first as a kind of harbinger, he allowed himself to think of what people might say. His death would confirm what many had long believed to be true about the bachelor farmer and the bachelor vet. But what did it matter to him what they said? He’d be dead. By that logic, however, why die? If it wouldn’t matter to him what they said when he was dead, why did it matter so much what they thought while he was alive?

There was still the fact that everything he saw reminded him of Chester. There was nothing down there that didn’t reflect him, like a collusion of light and mirrors. Ernie didn’t know anymore how to act, how to be. The simple ritual of making coffee stupefied him. Even the animals frustrated him now. He’d sold the milk cows after Chester died, but he was still responsible for the dog, the barn cats, fourteen steers, and one arthritic mare. What bothered him most was their hunger, which he’d always bowed before as though it were an idol. They would not grieve for him when he was gone. They would grieve that the man who fed them wasn’t there to feed them. They would know only their hunger. Still, he hadn’t been able to walk to the silo without filling the cats’ dented pan with milk, and giving Suzanna an extra scoop of oats, and forking the steers’ feed trough full of hay.

He looked down and was reassured that the land would indeed kill him. Seeing that this was true made his stomach double over. Again it helped him to imagine simply stepping forward into the air and the land itself doing the rest out of obedience and mercy. It would not merely cripple him, there was no danger of having to drool away the remainder of his years in a nursing home, unvisited and unloved, paralyzed so that he couldn’t even lift a finger against himself. The land would obey him as it always had.

Sunset, he’d promised himself. When the sun was completely gone, he would leap. It was a brutally cold clear blue day and there were no clouds to confuse him. The molten orange sun was just touching the tops of the trees far to the west, where the Mississippi was. It would be a little while, though, before it disappeared. But how arbitrary to wait for the sun to set. Why not jump now? So easy to step forward. One step. Now, were you supposed to take your hat off, as if entering a cathedral?

On the dome of the silo above and behind him landed a pigeon. Ernie wondered why it wasn’t out there with the others, but the way the pigeon kept ducking its head like a boxer, it struck him that the bird was either ill or retarded. Realizing he’d never really looked at a pigeon, he looked at this one with something like wonder. He had worked under their rustling in the barn and cursed their droppings and even once upon a time delighted in blasting them down from the rafters where they liked to line up, warmly cooing, their soft bodies like loaves of bread cooling on a shelf. It wasn’t until he met Chester that he had stopped killing them.

He was moved by the urge to touch this pigeon, the last living thing he could make contact with. But the bird was perched just too far away for him to reach, although not so far that he couldn’t see its eyes, which appeared to be coated with a fine dust. To be held was probably all it didn’t know it wanted. But even if he could scurry up the side of the dome and reach it, the bird would probably fly away, and even if he caught it, he would be holding a pigeon on top of a silo, and that was not what he had climbed up there to do.

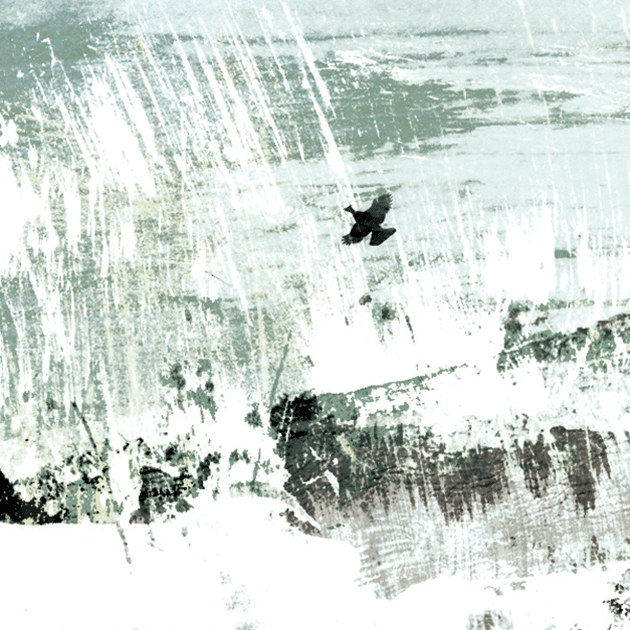

Damn the pigeon. Mite-ridden, salt-and-pepper-colored creature trying to save him. For a moment, he had a maddening thought. What if the pigeon was actually Chester, ignorantly assuming that Ernie wanted to live? He clapped and screamed to scare the pigeon off, but it just shuffled around on the dome, lifting one orange foot and then the other like someone stepping into a bath and finding the water too hot. For the first time, it blinked, and Ernie realized the sun was gone.

He turned to the west and proved to himself that the sun was no longer there. It was daybreak in China. He would have to leap. He took his hat off, went to the edge of the balcony, and let it drop. The air seemed to put on the hat and then take it off, and it fell like a leaf falls, now fast, now slow, now straight, now in jaunty swoops. It fell right side up on the gravel. To Ernie it looked like a tiny black hole, something to aim for.

He felt sorry for the person who would find him. He pictured his body crumpled on the ground — how would it come to rest? Certainly not as perfectly as his hat had. Perhaps he would lie there like a sleeping boy, his hands curled into little fists, his blood on the gravel. His knees suddenly gave out like hinges. He sat down on the balcony, his legs dangling over the edge, as though he were perched on one of those summertime piers in the north woods. He remembered sliding slowly into the cold water, cold even in July. He remembered being fascinated by the beautiful bodies of his older cousins. Unlike him, they dove right off the pier, trusting that the water was deep enough and not minding the cold. It was harder for him. He had to ease himself into it slowly.

He slid down until he had to hold on to the railing to keep himself from falling. To let go of the railing was to let go of his life. The cold rapped his knuckles like a pair of pliers. Soon it would rap them hard enough that he would simply let go. Out of curiosity, he writhed around and saw the pigeon and knew that it was just a pigeon and not Chester. It was a pigeon and it didn’t care if he let go or not. The pigeon wasn’t even looking at him anymore. It was looking out over the fields at the flock it couldn’t join.

Ernie pulled himself up onto the balcony. He lay on his back and tried to weep but no tears came, and he wondered if they were frozen in the ducts. He wished he could tell himself that something miraculous had happened, that he had experienced some sort of revelation, but he couldn’t, and he had to accept that he had been saved not by an act of grace but by the serene boredom and indifference of a retarded pigeon.

He took the descent rung by rung, conscious that he was shaking and forgiving himself for this. When he reached the part of the ladder where the safety cage ended, he knew he had returned to the earth of pigeon droppings and of graves, where the only tavern was Morton Saint’s Tap. Hopping down onto the gravel felt as strange to him as hopping down onto the moon must have felt to Armstrong. He walked over and retrieved his black hat, blew the dust off the brim, and went straight to his truck.

At first he had no idea where he was going, aware only of his hands on the wheel steering him somewhere and the black hat on the seat beside him. When he reached town, it was strange, as if he were dreaming. The first person he saw was a man coming out of Hardware Hank’s turning his collar up against the cold, carrying a white plastic bag that looked like it was filled with knives. That there were people coming out of hardware stores at dusk on a day that didn’t exist was remarkable to Ernie, almost funny. He thought for a moment that this was what he had driven to town to see — to prove that, like the pigeon, the whole human race was indifferent to whether he lived or died, that had he jumped, this man would still have walked out of Hardware Hank’s and turned his collar up against the cold. But then he was parking in front of Morton Saint’s Tap and walking toward the door. He opened the door and stood on the threshold. The place was even louder than it was most Friday nights, as if everyone had decided to celebrate Leap Day as some sort of holiday. They all turned and looked at Ernie standing there in a charcoal suit with a black hat in his hands and then the place grew quiet.

“What’s the big occasion, Ernie?” asked Bill Dietmeier, one of the men who’d written to the newspaper about Brokeback Mountain.

“I just spent the last hour on top of my silo, thinking pretty hard about jumping off it,” Ernie said.

“Well,” Bill said, “looks like you changed your mind.”

“We’re glad you did, Ernie,” somebody chimed in.

“Now come on over here and let us buy you a beer or two,” somebody else said. After a moment spent studying his hat, Ernie raised his head and said, “I want you all to know I loved Chester Bradbury.”

“We know you did, Ernie,” somebody said.

“Chester and I were lovers.”

“I think a few of us figured that,” somebody else said.

“I miss him like hell,” Ernie went on, no longer in the same bar as they were.

“You’re not gonna go back and hurt yourself now, are you?”

“Come on over here and have a beer.”

But in his mind Ernie wasn’t standing in the open doorway of Morton Saint’s Tap in Pearl City, Illinois, letting all the cold air in. He was in another tavern and everyone looking at him was dead. Knowing that the beer would taste better than it ever had and humming along with a song only he could hear, Ernie Boettner let the door close and walked down to the end of the bar where no one was sitting. He sat down and put his black hat on the stool next to him so there would be no mistaking that he was saving it for someone.