One day this April, two weeks after the Israeli elections gave Benjamin Netanyahu a fourth term as prime minister, the morning after the framework for a nuclear agreement with Iran was worked out — the morning, as it happened, of the Passover seder — I dropped in at my local cheese shop, which is set back from the main street of Jerusalem’s German Colony. The neighborhood, once the heart of the city’s secular community of Hebrew University faculty and government workers, is now dense with yeshiva graduates wearing the signature knitted yarmulkes of the settlers, the ultra-Orthodox, and the affluent “modern Orthodox” from Toronto, Paris, and Teaneck, New Jersey. The clerk behind the counter — we’ll call him Shachar — the clever, chubby grandson of Polish Jewish immigrants, whose eyes told you he thought he was meant for something better, had hooked me on truffle cheese some years ago, and we often had pleasant conversations when I came in for regular fixes. We did not normally talk politics, except for the occasional sigh over news of corruption or violence. (His grandfather, he had told me, had been a cadre in the Irgun, the militant Zionist underground group.) This time, however, he was buoyant, expectant. “Are you pleased with the election?” he asked me, using the Arabic colloquialism mabsoot for “pleased,” as casually as if he were asking whether Passover came in spring.

“Are you out of your mind?” I erupted. “I feel shame for this country.”

Shachar stared at me, more surprised than wounded. I was taking advantage of him: I was his customer, after all. I shifted my tack toward patriotism. “Shachar, how can we be pleased? We think we are the only people in the world who live with threat, but we have to work with regional leaders who will work with us. Bibi is taking the country into unprecedented international isolation.”

This gave Shachar his opening. “No,” he replied, “the problem is with Obama. Experts say relations with America have never been better except for him. He doesn’t understand what we’re dealing with here. People on the left” — he meant me, but graciously kept away from the second person — “think they know better but never learn. My other customers from America say he is the worst president ever. Soon we’ll have missiles at Ben Gurion Airport.”

“Chair (Hebron),” by Adam Golfer, taken near a Palestinian market, directly under an apartment building where Jewish settlers live

I stiffened my back and told Shachar what I thought of his government, his experts, and his other American customers. But even before I ended my disquisition, I thought: I am missing the point. One lesson the Israeli left has refused to learn is that elections are not so much a clash of arguments as an occasion for trafficking in fear. Shachar’s instincts were closer to primordial, and it was such instincts that determined the vote in Jerusalem, and much else in Israel. Netanyahu played on this fear by warning about “Arabs voting in droves” during the election’s closing hours — but Shachar’s real impulse was to find safety in affinity: the sense that things very nearby were dangerous, or could suddenly be made so; that understanding both sides of an argument weakens resolve; that believing in negotiations makes you unfit to conduct them.

You’d think we would have learned some political lessons by now. This election was the ninth since 1977 in which parties that challenged Netanyahu’s Likud and its ultraright offshoots ended up with just under half of the vote, and left their liberal supporters angry and dumbfounded. About 70 percent of Jerusalem’s citizens had voted for the various ultraright parties that eventually made up Netanyahu’s governing coalition. These days you pick up the morning paper and feel a thousand cuts: watchdog groups combing Israeli high schools and universities for teachers and professors whose “Zionism” is suspect; Netanyahu using the regulatory powers of the Communications Ministry to entice, or threaten, major media outlets to be friendly to him; the coach of Jerusalem’s soccer team explaining why its fans aren’t ready for the team to recruit any Arab players. The most common impulse, especially among the young, is to avert one’s eyes. In April, Israeli newspapers reported that Gaza’s water table was on the verge of collapse, as if Gazan children weren’t already miserable enough. They warned of “thousands of Gazans rush[ing] the Israeli and Egyptian fences” to plead for a drink in the coming summer’s scorching heat. Just after this warning it was reported that Israel ranked eleventh in an international happiness index, up there with Switzerland; a popular radio host, Judy Mozes, seized on the second report and, seemingly oblivious to the first, said delightedly, “Israel is always bathed in sun.”

The government has razed illegally constructed homes in Israeli Arab cities, after blocking their legal construction. Meanwhile, rabbinic courts, which have strengthened their control over marriage and divorce, have begun blacklisting female “adulterers.” Likud and its coalition partners promise to revive a bill that defines Israel as “the nation-state of the Jewish people” — not, pointedly, a state of its citizens, a fifth of whom are Arabs — and demotes Arabic from an official language to something subordinate. This bill envisions Jewish law and heritage serving as an “inspiration” for national laws, mandates that all state symbols be Jewish ones, and reserves the right of citizenship and freedom of movement exclusively to legal Jews — defined as such by the ultra-Orthodox rabbinate. If enacted, the bill would seriously undermine Israel’s Basic Law of Human Dignity and Liberty, the closest thing the country has to a bill of rights.

An Israeli soldier casts his ballot for the parliamentary election at a mobile voting booth in the West Bank Jewish settlement of Migdalim, March 17, 2015 © Reuters/Amir Cohen

Recently, a split decision of the High Court of Justice, usually thought of as the last bastion of Israeli liberalism, upheld a law passed by Netanyahu’s last Knesset that allows litigation against anyone who boycotts the products and colleges of West Bank settlers, something my wife and I have been doing for some time — a nonviolent, safely bourgeois form of protest, we thought. In his majority opinion, Justice Elyakim Rubinstein wrote:

The Passover Haggadah discusses this same promise from heaven regarding the survival of the Jewish people despite [the ploys of] its enemies: “And it is this [covenant] that has stood by our fathers and us: For in every generation they rise up against us to destroy us, but the Holy One, Blessed be He, saves us from them.” There’s nothing wrong with the Israeli Knesset giving legal expression to the battle against those who are rising up against us to destroy us.

“Giving legal expression to the battle against those who are rising up against us to destroy us” is, ironically, a paraphrase of Pharaoh’s justification for killing every son born to Hebrew slaves. Justice Rubinstein neglected to add that the Haggadah, the guidelines for the Passover seder, also calls for nurturing “all who are hungry,” and asks every generation to imagine “leaving Egypt,” moving from “slavery to freedom,” just as those gospel songs imply.

The most important party that aimed to displace Netanyahu, Isaac Herzog’s Labor Party, tried to pander to people like Shachar, hauling out retired generals to endorse it, merging with Tzipi Livni’s small centrist Hatnua party, and renaming itself the Zionist Union. But Herzog and Livni never really addressed Shachar’s fears. They made what has become the peace camp’s ritual claim: that the occupation forces Israelis to choose between a Jewish state and a democracy. They assumed that most voters would refuse to sacrifice either, and would instead push to end Israel’s rule over Palestinians. But for residents of Jerusalem especially, the peace camp’s claim only strengthens the impulse to reduce or hem in the Arab population: to prompt West Bank Palestinians to move over the Jordan, overthrow the Hashemite monarchy, and make their state on the East Bank.

Left: Men erect a plaque commemorating two Israeli traffic policemen who were killed on duty in the West Bank, close to the Jordanian border. Right: A rock from Masada, a site of ancient palaces and fortifications in the Judean Desert. During the First Jewish–Roman War, a siege of the fortress by the Roman Empire led to the mass suicide of the Jewish Sicarii rebels, who preferred death to surrender. Photographs by Zed Nelson

The more pressing problem, a vulnerability that has deepened in spite of Israel’s growing capacity to deter an invasion or an attack from the outside, is that there is too little space for so much grievance. Israel and Palestine north of the Negev Desert together contain some 12 million people within about 5,000 square miles. Their populations share, in effect, an urban infrastructure and, in spite of the tensions, a common business ecosystem, in which Jordan is also a player. (Amman was largely built by the Palestinian bourgeoisie.) They draw water from a common water table and share sewage-treatment facilities. They share a wireless spectrum, diseases, tourists. A robust Palestinian economy is unimaginable without an end to the occupation, but it is equally unimaginable without Israeli and Jordanian intellectual capital. So any plausible configuration of the two states must also have a common security environment: that is, a common police force, or at least a very high level of security cooperation, that is backed by international monitors and encourages Jordanian participation. In the absence of something along these lines, the occupation seems almost benign by comparison with the chaos that could conceivably occur. Leave aside the violence between Shia and Sunni that is tearing Syria, Iraq, and Yemen apart. A missile fired from the territories could indeed hit an El Al plane on its glide path, just as a yeshiva seminarian off the plaza in front of the Wailing Wall could try to blow up the Al-Aqsa mosque. Majorities on each side may wish for peace, but the means of violence at the disposal of terrorist outliers is great enough to pull down any structure of peace — if, that is, each side holds the government of the other side responsible for random acts of radical hatred. In the best of all possible worlds, Palestinians and Israelis would be deeply interdependent but also deeply fragile: hostage to acts that would polarize the sides and evoke all the old enmities.

The Labor Party, and peace advocates more generally, refused to engage at any level of detail this time around. Being centrist meant appearing tougher than the left, which meant being too skeptical of the Palestinians to bother floating plans: the party offered nothing concrete about how the two states might work together; there were no demonstrations of cooperation. Herzog and Livni vaguely endorsed the Arab peace initiative of 2002, but they avoided meeting with Mahmoud Abbas, the president of Palestine. When forced to present an actual strategy, they spoke abstractly about separating the populations, a proposal that implied two independent states, which only made things worse. For most Israelis — most Palestinians too, according to West Bank polls — peace was impossible to imagine if it meant trusting the seriousness of the other side’s intentions and respecting the other side’s sovereignty.

But what other language was available? The obvious word, “confederation,” felt too much like a compromise of sacred notions of Jewish sovereignty, and demanded too much faith in the Palestinians. Since before the Oslo Accords, peace advocates have spoken instead of core problems — security, borders, Jerusalem, refugees — as though the solutions to these problems could be found by two separate, sovereign governments. Secretary of state John Kerry, by all accounts, based his failed shuttle diplomacy on this agenda. A few weeks before the election, the writer Amos Oz put things urgently, and with the mandatory reservations, in a speech: “We and the Palestinians cannot become one happy family tomorrow because we are not one, we are not happy, and we are not a family. We are two unhappy families. We need a fair divorce and not a honeymoon.”

The point is, security will be meaningless to people like Shachar unless the other problems can be resolved within political models that impose a high degree of mutual constraint and include Jordan in the mix. This is no longer the landscape of the 1950s, when “divorce” seemed plausible — when a couple of million people on each side of the Green Line that divides Israel from its Arab neighbors competed to control the hilltops so that their respective farmers could plow the valleys. Each side is now connected to the other as much as to anywhere else. Talk of separation only mocks the condition that Israelis and Palestinians find themselves in.

Curiously, proposals that gesture toward a confederation have been missing from the discourse of the peace camp, though the idea has been yanked in every time good-faith negotiations for two states have taken place: the joint patrols and security cooperation that were featured in the 1993 Oslo Accords, the virtual common market that was envisioned by the 1994 Paris Protocol. A shared municipal government for Jerusalem and an international custodian for the Old City were both contemplated during the 2008 negotiations between Abbas and former Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert. Even on the Palestinian right of return, Olmert and Abbas agreed on an “international commission” for compensating and resettling Palestinian refugees. As I have written in these pages before, a confederation would make it easier to solve the vexed problem of “return,” since residency could then be distinguished from citizenship. Some settlers could remain Israeli citizens yet live outside the Green Line; some Palestinian refugees could become Palestinian citizens yet live within the Green Line.

After the election, and to his credit, Israeli president Reuven Rivlin, a former member of Likud, gave an interview to a group of journalists in which he seemed to grasp the conundrum. “Maybe we can live in a federation,” he said. “We will not have peace unless we have open borders.” More recently, Yossi Beilin, an architect of the Oslo Accords, endorsed the idea of a confederation in a New York Times op-ed. He recalled that he and his former Palestinian interlocutor, the late Faisal Husseini, had discussed such an arrangement before the Accords were signed. But during the election, Herzog and Livni were loath to mention the idea, since it could be so easily mischaracterized as suggesting — how did Oz put it? — “one happy family.” Instead they advanced the older ideal of separate states, the flip side of a so-called Zionist solidarity that makes little room for Arab citizenship. It is as if the peace camp were saying: the Jewish state doesn’t want so many Arabs, so let’s give them land of their own and maybe they’ll leave us alone. Shachar wasn’t buying it.

Netanyahu had no good answer to the prospect of “missiles at Ben Gurion Airport.” His presumption that Israel must be resigned to regular rounds of violence has only increased the potential for attacks from outside Israel — from Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza. What Netanyahu does have is a simple (and crafty) “no.” The status quo has legitimized the environment he wishes to maintain: the occupation, which purportedly exists to foil Palestinian enmity, manages a burgeoning network of informers and furthers the creeping annexation of the West Bank, the “land of Israel.” Since the election, his government has announced new construction in East Jerusalem. So Netanyahu gains merely by obstructing change, freezing voters in place, at once fomenting the fear and exacerbating the threat. He demands that Abbas accept Israel as a Jewish state, as if the fragility created by Israel’s geography and demography can be obviated by Palestinians endorsing the Zionist narrative. Abbas, of course, refuses to entertain the idea, not least because a fifth of Israeli citizens are Arabs. But that causes no problem for Netanyahu; Abbas cannot control Hamas, and so there can be no Palestinian state anyway. There is “no partner,” he says, so he will not accept Kerry’s framework for peace — not unless Palestinians can prove they can be trusted. And that can only happen if they demonstrate a frame of mind that would have precluded any conflict in the first place.

There’s an analogy here to the political genius of congressional Republicans in the United States, Bibi’s friends, who have likewise gained by elevating inertia to a principle of action. They know that they cannot say they are for keeping things as they are, which would make them advocates for plutocracy and inequality, for which there is no majority. So instead they say that they are only against “government,” and act in ways to resist or sabotage the workings of the state apparatus. Ordinary people start saying that Washington is broken, journalists flock to valorize the voice of the frustrated citizen — and Republicans win. It’s the perfect con.

Netanyahu has his own version of a con. He knows that he cannot just say that he wants Greater Israel for neo-Zionist reasons; there is no electoral majority in support of the settlers. So instead he merely derides “trust.” Established facts do the rest. (Machiavelli figured out this ploy a long time ago. “There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success,” he writes in The Prince, “than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things, because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new . . . [but] do not readily believe in new things until they have had a long experience of them.”)

Netanyahu cultivates an atmosphere of morbid frustration, an uncertainty about Israel’s staying power that owes more to the ground of Jerusalem than to the skies over Tel Aviv. The uncertainty grows every time a young Palestinian fanatic blows up Israeli civilians in a quiet restaurant and leaves behind a video of himself quoting the Koran. For people in Greater Tel Aviv, the Palestinian state is a kind of defensible abstraction; more than 60 percent of the electorate there voted for the parties opposed to Netanyahu. For Shachar, and for me, the Palestinian state would be virtually around the block. Within a mile of our neighborhood, there were a dozen bombings of restaurants and buses between 2000 and 2004. Much of the recent electoral campaign was taken up by Netanyahu’s controversial speech to Congress and his railing against Obama’s Iran deal. We heard talk of Islamic enmity and existential threat. But this preoccupation with Iran is deceiving. Attitudes about Iran do not eclipse the despair about the Palestinians but are rather the product of it.

Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, Netanyahu and his ministers insist, must be “dismantled and neutralized,” their euphemism for the Iranian regime simply disarming and surrendering under the threat of an American military strike. He complains that Obama’s projected deal settles for a plan to “freeze and inspect.” Ehud Barak, Bibi’s former defense minister, who had also strongly advocated in Washington for an American bombing run on Iran’s nuclear installations, told CNBC in April: “Either they dismantle their military nuclear program or else.” Or else what? In a similar vein, Netanyahu insisted again and again that increased economic pressure and the threat of military action would force Iran to capitulate to a “better deal” — one, he suggested, that would end all threats against Israel, irrespective of the Palestine issue.

In truth, however, Netanyahu has not been able to bring even Hamas’s comparatively puny forces in Gaza to capitulate, not after years of economic strangulation and, recently, tens of thousands of shells and air strikes and thousands dead. Intimidation may bring Republicans to their feet but not Iranians to their knees. Nor does Netanyahu, Barak, or anyone else have any idea where an American strike against Iran might lead. Consider that Iran can seriously disrupt shipping in the Persian Gulf, that Iran’s proxy, Hezbollah, can use its advanced missiles to shut down Israel’s economy. Consider, too, that America cannot tolerate the former nor Israel the latter. These facts add up to the ideal ingredients for a regional conflagration, and yet this logic does not seem to shake Netanyahu’s determination. He may fancy himself a new Churchill given another chance to preempt Hitler in 1938. But he sounds more like Curtis LeMay, the Air Force general who headed the Strategic Air Command and said in 1965 that China would have the capacity to deliver bombs as soon as twenty-five years in the future, and that therefore the United States should entertain the “destruction of the Chinese military potential before the situation grows worse.”

What Netanyahu did not say, what every Iranian leader and any reader of Jane’s Defence Weekly knows, is that Israel is the world’s sixth most powerful nuclear power, with a second-strike capacity: upward of 200 warheads that can be placed on airborne and submarine-based missiles. Being willing to incinerate Tel Aviv (which, by the way, also means irradiating Gaza and the West Bank) would mean being willing to sacrifice Tehran, Qom, and Isfahan. Nor can Netanyahu claim any special insight about what leaders will do when they have the capacity to kill an enemy’s civilization at the risk of having their own killed in retaliation. He has been selling the idea that Iran’s bomb is a genocidal threat, but he’s been counting on ordinary Israelis thinking of the bomb as an enormous suicide vest. The opportunity that Netanyahu has failed to embrace with Iran — and not coincidentally, also with Palestine, particularly Gaza — is a diplomatic process, like Richard Nixon’s with China, based on reciprocity and international guarantees, economic rehabilitation, and, eventually, a generational change in attitudes. Netanyahu’s rhetoric was righteous, mythic, self-aggrandizing; the Intifadas, seared in Israeli imaginations, provided the images.

Yet it would be wrong to assume that future Likud victories are secure. The Orthodox and ultraright parties that were the foundation for Netanyahu’s earlier coalitions won only fifty-seven seats in this last election. Two years ago, they won sixty-one; in 2009, sixty-five. The coalition that Netanyahu put together this spring rests on a one-seat majority.

The real story of the recent election was the emergence of an Israeli center: represented not only by Herzog’s merger with Livni, which won twenty-four seats, but also by Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid (“There Is a Future”) and Moshe Kahlon’s Kulanu (“Together”) parties. The latter two won twenty-one Knesset seats, or 18 percent of the total, and seem to be gaining in popularity. Israel’s electoral landscape is changing; Kahlon, a former Likudnik from a Libyan family, gave Netanyahu his majority and can, at any time, take Netanyahu down.

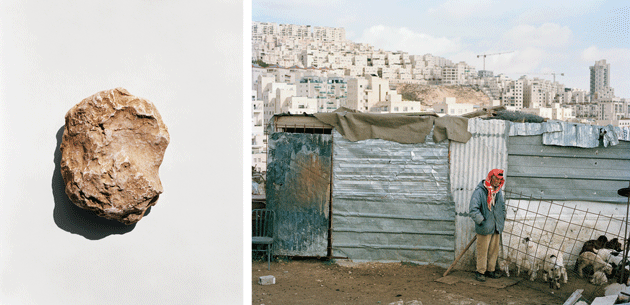

Left: A rock from Deir Yassin, a Palestinian-Arab village that was attacked on April 9, 1948, by Jewish paramilitary fighters who were attempting to break an Arab blockade of nearby Jerusalem. Right: Said Zawahari, seventy-four, a Palestinian shepherd, outside his small farm. Behind him is the vast Jewish settlement of Har Homa, in the West Bank. Photographs by Zed Nelson

Kahlon’s and Lapid’s parties are focused in slightly different ways on economic inequalities, but they also emphasize social liberalism (gay rights, religious freedom), and therefore get votes in the major cities. They are careful to distance themselves from the ideological right. Yet they are mainstream — which is to say, militant and dismissive — where the Palestinian peace process is concerned, and they speak of Jewish national solidarity — their version of Zionism — in apologetic ways that imply a favored legal status for Jewish citizens not very different from Likud’s position. They are rightists in the sense that they are reactionary, and therefore skeptical of the left, but centrist in their unwillingness to be identified with either Arabs or settlers.

Their most significant gains are among Israel’s young, a difficult concept in the context of Israel, since it pertains to the children and grandchildren of immigrant groups who came at different times (so that, for instance, younger voters from self-identified Moroccan families can be in their forties and fifties, and younger Russian voters in their thirties and forties). The mean age in Israel is around thirty; pollster Dahlia Scheindlin told me that young people who lean toward the center “are tired and despairing of the ideological claims and don’t really believe the conflict can be solved; so they connect to fresher politicians, to ‘quality of life’ ” issues: “The electorate now supports two significant center parties, and many of their votes come from kingmaker demographic groups who used to favor the right: Russian immigrants and Mizrahim — the generation of Russians who have grown up in Israel and the third-generation Mizrahim.” (Mizrahim are Jews from Arab countries.) This younger electorate follows the Cleveland Cavaliers, travels to Peru, sells to Berlin. They expect to fly with a passport that they won’t have to keep hidden when they land.

Younger voters who animate the center constitute a departure from the identity politics that used to all but guarantee Likud its victories. For a long time, Israeli pundits have spoken almost universally about five (at times overlapping) electoral “demographics,” each of which represents about 20 percent of the population: veteran, pioneering Europeans; Palestinians who became citizens after 1948; Mizrahim; stridently Orthodox Jews of all kinds, Zionist or non-Zionist; and immigrants from the former Soviet Union. For very old reasons, Likud has long held a hugely disproportionate appeal among the last three groups. Mizrahi voters in particular resented the secular, European Jewish Labor establishment that controlled the economy and seemed to condescend to their traditional religiosity when they arrived after 1948. But among Israelis aged eighteen to thirty-four, the issues are not so clear. Alongside the expected social liberalism there is a stronger trend toward religiosity than among older Israelis — “more Jewishness, less Israeliness,” as a friend put it. My impression, from dozens of conversations, is that younger “Russians” are more cosmopolitan than their parents. Mizrahi youth, too, expect to be in the world, and are ambivalent about the money spent on settlers. What’s more, young Israelis intermarry at so high a rate that the division between Ashkenazim (Jews from Eastern Europe) and Mizrahim seems increasingly strange to them.

Still, they despair that diplomacy can achieve any results with the Palestinian Authority, and they regard Hamas with loathing. They may be less ideologically fixed than their parents, but they are more easily impressed by personalities, headlines, and world events. Their associations are reflexive: “America?” Freedom. “Washington?” Friendship. “Europe?” Hypocrisy (and vacations). “Values?” Army service. “History?” Holocaust. “Orthodox?” Spongers. “Arabs?” Chaos. “Palestinians?” “Fuck ’em.” (Shachar, I later learned, voted for Kahlon.)

Poor, less-educated Mizrahi voters, especially those who live in small cities outside the Tel Aviv–Haifa urban corridor — cities such as Ofakim and Ashdod, places to which the state’s Labor Zionist founders sent them when they arrived destitute — vote as consistently for Likud as poor evangelical whites in Indiana vote Republican. The more recently arrived Russians, for their part, reject any parties that carry the scent of socialism; they like the Putinist strongman talk they hear from Likud leaders such as Netanyahu and Ariel Sharon, and think their cynical view of international affairs to be only realistic. As for “halachic” Israelis — an incongruous mix of ultra-Zionist, Orthodox settlers and non-Zionist, ultra-Orthodox theocrats — they mostly support Likud because of that party’s peculiar notion of Israel as a state of world Jewry that subordinates democratic liberalism to rabbinic influence.

The resentment goes both ways, though it is not politically correct to say so. During a mass rally of peace groups in early March, which was meant to showcase an attack on Netanyahu’s Iran policy by Meir Dagan, a former director of the Mossad, the artist Yair Garbuz complained that the state was controlled by “amulet kissers, idol worshippers, and people who prostrate themselves at the graves of saints.” In April, a document from 1962 was released in which David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founding prime minister, admitted his disdain for the lack of education among the Mizrahim. (“The problem is . . . [t]hey will be the majority of the nation,” he told a colleague in the recently disclosed document: “They have six-to-eight children and the Ashkenazim only two children. . . . The question is whether they will lower the nation or [whether] we will succeed by artificial means and with great efforts to elevate them.”) The Labor Party, in this context, has for two generations been reduced to counting on the vote of the children and grandchildren of revolutionary European Zionists who thought that by emigrating to Israel they were inventing a modern social democracy and secular Hebrew culture.

Herzog knows that he could never win a Knesset majority without the center parties and their xenophobic youth vote; nor, ironically, could he succeed without parliamentary support from the Arab parties. The balancing act can be gyrating. In a speech from the Knesset podium, Herzog went out of his way to condemn Netanyahu for his (now famous) racist incitement against Arabs, yet the name Herzog chose for his merged party, Zionist Union, was itself a signal to centrist voters that he and Livni would put up a keep out sign for Palestinians. A big-tent democratic party, one that absorbed and superseded Labor, would be the obvious next step to court voters who support parties now in opposition: leftists, more liberal centrists, and Arabs (very few Arabs would support Likud in the Knesset). It was Labor’s military leaders, people like Herzog’s father, Chaim, the sixth president of Israel, who defeated and expelled — or just didn’t let back — the Arab refugees of 1948. The hawkishness of the center parties reflects a dark anxiety, but these parties might also, in time, offer a solution, precisely because they lack ideological rigor. The young might change things, in other words — for that is what young people do — but they would need a hope, and a fear, in the foreground to eclipse the background threat that Netanyahu relies on.

I am speaking, of course, of bringing international, and mainly American, pressure to bear. How the Netanyahu government deals with Palestinians under the occupation, and, correspondingly, how it deals with its internal Arab minority, is not merely an internal affair — certainly not given Israel’s claim on the military and economic resources of the United States. The imperative to deal with these matters might be seen through an analogy suggested by an unexpected source. If the Israeli election produced anything like a transformational leader, it was not in the Jewish left but in the Arab mainstream: Ayman Odeh, the forty-year-old lawyer who helped found a new party, the Joint List — an amalgamation of mainly Arab parties. The party, which Odeh now leads, captured thirteen Knesset seats. He demonstrated, among other things, that leadership of the Arab community has passed to a younger generation of professionals who do not dwell in the past but are focused on giving Israeli citizenship a secular meaning. He debated rightist leaders with remarkable dignity, rejecting discrimination on the basis of religion or ethnicity and arguing for the integration of Arabs into a broadened civil society. When Ethiopian Jews protested against discrimination on the streets of Tel Aviv, Odeh marched with them. “Just as Jews in the U.S. joined Martin Luther King,” he said, “I’m sure hundreds of thousands of Jews will join the struggle for civil equality in Israel.”

Odeh’s analogy to the American civil-rights movement may be a little wistful, but it’s not that far-fetched. Like American Southerners in the Sixties, most Israelis feel that they are the custodians of a quasi-divine cause, one born of terrible sacrifice and engendered by memories of slaughter. For Jewish Israelis to acknowledge that justice is necessary for the subjugated minority in their midst is often seen as a betrayal of the foundational story people tell and retell in order to achieve cohesion. Integration seems a menacing abstraction when compared with the memory of the events that suggested the need for a Jewish state. But Israelis also expect to be part of a wider world, and espouse, even if they do not fully enact, the norms of liberal democracy. Which is another way of saying what Odeh may think but does not admit: that this is a society that will generate something like Netanyahu’s infuriating majority for the foreseeable future — unless there is pressure from the outside, in which case serious change will almost certainly come.

A majority for change can be built, in other words, but not in the absence of pressure from Washington. Barack Obama undoubtedly hopes to make a difference before he leaves office, if only to pose a moral alternative to Netanyahu’s stridency, much as Odeh does. And Obama obviously wishes to leave a legacy of progress toward a Palestinian state, which would improve Jordan’s chance of survival and calm anti-Americanism in Arab states. The question is, what kind of pressure will accomplish more than vague allusions to “two states”?

Wendy Sherman, an undersecretary of state, told American Jewish leaders in April that the administration will be “watching very closely to see what happens on this [Palestinian] issue after the new government is formed.” She implied that if the Netanyahu government continued to block a Palestinian state, as Netanyahu said he would during the election, it would “be harder” for the administration to block resolutions in the U.N. Security Council endorsing a Palestinian state along the 1967 borders. (The French are likely to introduce just such a resolution in the coming months.) This warning was long overdue. The Obama Administration had no defensible rationale for vetoing resolutions condemning the settlements or backing a Palestinian state, except as concessions to Netanyahu and AIPAC, who insisted that all issues should be left to bilateral negotiations. In 2009, Netanyahu refused to negotiate on the basis of what was agreed between Abbas and Olmert, and, in 2011, he torpedoed a framework agreement that had been worked out between Abbas and then Israeli president Shimon Peres. Kerry, who failed to mediate an agreement last year, eventually came to the conclusion that Netanyahu was just stringing him along. The conclusion was belated at best.

But “watching very closely” hardly seems enough at this point. The composition of Netanyahu’s new government does not portend anything but the continuation of his cynical game. It is stacked with partners who have made their careers promising privileges to those with J-positive blood. Naftali Bennett, for instance, the leader of the Jewish Home party, who thinks that Gaza should be invaded, gay rights are wrong, and university intellectuals should stop apologizing for Jews taking back their land, is the new minister of education. Ayelet Shaked, a powerful figure in the Jewish Home party, is the new justice minister. Likud’s own Miri Regev, who has campaigned for the expulsion of Sudanese refugees and said that she is “happy to be a fascist,” is the new culture minister. Uri Ariel, a settler leader, is the new agriculture minister. In all, Netanyahu promised ultranationalist and Orthodox leaders that he would provide about $500 million for new housing in East Jerusalem and for new Orthodox schools at all levels in which subjects like math, science, and English will not be taught. In Israel the head of the government cannot just appoint whom he or she pleases to the cabinet; the party leaders of Likud and its ultraright coalition partners share the task of governing. To imagine that some new Netanyahu pronouncement endorsing two states will mean an actual change of policy is to believe that a government of John McCain, Dick Cheney, Ted Cruz, Sarah Palin, Pat Robertson, and Marco Rubio would expand the Affordable Care Act because they condemn “inequality.”

If Kerry wants to make a difference, he cannot fall back on vague formulations. He told a congressional committee in the spring of 2014 that it had been a mistake to allow Netanyahu to hinge progress on Abbas recognizing Israel as a Jewish state. That’s a start. But Kerry cannot expect any peace process to work if he fails to sketch out a detailed plan for security cooperation between Israel and Palestine, with international forces on the ground, beginning with setting terms for rehabilitating Gaza. Any suggestion advanced by Obama, or by Hillary Clinton, for that matter, that Abbas needs to resolve matters with Israel through bilateral negotiations should be dismissed as cynical and cruel. Netanyahu’s government will not negotiate in good faith, and he will not stop the settlement project while negotiations are under way. Nor, paradoxically, is diplomatic caution likely to mitigate violence. The opposite is true. A fuzzy vision for the future will be filled in by ordinary Israelis and Palestinians with apocalyptic imaginings culled from past atrocities. Mohammad Mustafa, the head of the Palestine Investment Fund, told me that, before the Oslo process began in 1993, per capita GDP in the Occupied Territories was about a third more than Egypt’s; today it is a third less. And new violence in the West Bank will almost certainly spread to refugee camps on the outskirts of Amman. The collapse of Jordan, which has the Islamic State on its borders and is struggling to support a million Syrian refugees, is the next catastrophe that will result from failing to solve the Palestine situation.

Kerry should look beyond the Netanyahu government. He should make clear that the governance of Jerusalem and the holy sites of the Old City is inconceivable without shared sovereignty, which implies new confederal arrangements, and an international presence. He should understand that Jerusalem, over time, could serve as a model for an economic confederation of the two states. He should support any Security Council resolution that condemns the settlements and sanctions Israel for continuing them, not veto it, as the Obama Administration did in 2011. To avoid an explosion — which, alas, Israelis would never blame Netanyahu for — young people on both sides need to see a workable, reciprocal blueprint for their future.

But serious pressure can come from other Western societies too. Right now, in Israel, it is against the law for me to suggest that democrats around the world demand to know which products or professors come from the settlements, and boycott them, so I won’t do that. It is similarly against the law to suggest that FIFA boycott Israel’s national soccer team if it includes any players from teams that refuse to field Israeli Arabs, so I won’t do that either. I won’t say that Palestinians are justified in bringing the settlements and other violations of the Geneva conventions to the International Criminal Court. Some American Jewish organizations will call such pressure “anti-Israel.” I will say that this is nonsense. What Netanyahu proved when he spoke to Congress is that as America is divided, Israel is divided. Netanyahu chose which Americans he considered allies in his generalized war on terror and which he did not. Americans, too, have to choose which Israelis stand for democratic values, and which do not.