Flor Arely Sánchez had been in bed with a fever and pains throughout her body for three days when a July thunderstorm broke over the mountainside. She got nervous when bolts of light flashed in the sky. Lightning strikes the San Julián region of western El Salvador several times a year, and her neighbors fear storms more than they fear the march of diseases — first dengue, then chikungunya, now Zika. Flor worried about a lot of things, since she was pregnant.

Late in the afternoon, when the pains had somewhat eased, Flor thought she might go to a dammed-up bit of the river near her house to bathe. She is thirty-five and has lived in the same place all her life, where wrinkled hills are planted with corn, beans, and fruit trees. She took a towel and soap and walked out into the rain. Halfway to the river, the pains returned and overcame her. The next thing Flor remembers, she was in a room she didn’t recognize, unable to move. As she soon discovered, she was in a hospital, her ankle cuffed to the bed, and she was being investigated for abortion.

The Metropolitan Cathedral in San Salvador. All photographs from El Salvador, May 2016 © Nadia Shira Cohen

There are six countries in the world that prohibit abortion under all circumstances, without exceptions for victims of rape or incest or for cases in which the pregnancy threatens the life of the mother: El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Chile, Nicaragua, Malta, and Vatican City. In the United States, even the most fervent antiabortion groups maintain that women who have abortions are victims, instead directing their attacks at doctors. Earlier this year, when Donald Trump suggested that if Roe v. Wade were reversed, women who choose to terminate a pregnancy should be subject to “some form of punishment,” he was denounced across the political spectrum.

That scenario already exists in El Salvador, a country of 6.3 million, where an active medical and law-enforcement system finds and tries women who are suspected of having had abortions. Public prosecutors visit hospitals to train gynecologists and obstetricians to detect and report patients who show “symptoms of abortion.” Doctors are legally obligated to be informants for the police.

Salvadoran doctors at public hospitals must rely on after-the-fact evaluations, and women who suffer miscarriages or stillbirths immediately provoke distrust when they seek treatment. At private hospitals, however, patients can pay for discretion. In the capital, San Salvador, residents of the exclusive Colonia Escalón can arrange procedures at clinics for a thousand dollars; some women fly to Miami or Mexico City, if they can afford the ticket. Abortion is a poor woman’s crime.

The sentence is two to eight years in prison. But because El Salvador’s constitution classifies a fertilized egg as a legal person, in many cases prosecutors arbitrarily upgrade the charge to aggravated homicide, which carries a penalty of between thirty and fifty years in jail. (The aggravated-homicide charge is meant to apply to cases in which the fetus is more than twenty-two weeks old, but judges rarely learn the details of a pregnancy.) In July, the conservative party ARENA proposed to the Legislative Assembly that the minimum prison sentence for women convicted of abortion be raised to thirty years.

The day of the thunderstorm, Flor had gone out alone. She has five children, whom she has raised with her mother’s help — the man by whom she had become pregnant had left. Her brother Obidio and her son Mardoqueo Alonso work the fields surrounding their house, clearing the mountain with machetes, planting and harvesting the corn that Flor’s daughters grind and pat into tortillas. When Mardoqueo Alonso returned home, at around six in the evening, he noticed that his mother was missing. Normally he could see up to the river from their house, but the corn had grown high and blocked the view. It was getting dark, so he set out with a flashlight to search for her.

Mardoqueo Alonso found his mother lying on the path, unconscious and bleeding out into the soil. He called for help, and the family, along with a neighbor who works as a nurse, hurried to gather around her body. The neighbor said that Flor had to get to the health center in the nearest town, normally a twenty-minute ride in the flatbed of a truck down a rocky dirt road. No vehicles were available, so they lifted her into a hammock, and Obidio found long sticks to thread through either end. They hoisted it onto the shoulder of one man in front and one man behind, and began the descent. The storm had eased, but it was hard going, and six people had to take turns carrying Flor to town. She left a trail of blood down the mountain.

Women carry a statue of the Virgin Mary during the annual Flower and Palm Festival, in the town of Panchimalco

At the health center, nurses saw that Flor was hemorrhaging and called an ambulance to take her to the public hospital in Sonsonate, the closest city. A blood transfusion saved her life, but she remained in a coma. Doctors surprised her family by saying that Flor had just given birth. Where was the child? When they said they didn’t know, hospital staff called the local prosecutor, who alerted the police.

Obidio was shocked. While he knew that abortions were illegal, he had never heard of a woman being prosecuted for a miscarriage or stillbirth. But for someone accused of inducing an abortion, making those claims is the likeliest defense, he learned, so Flor’s situation was inherently suspicious. Obidio said that when the family gathered in the cornfield to save Flor, “We didn’t hear anything, we didn’t suspect anything. We were only scared of the hemorrhage, all the blood. She was dying.”

The following morning, Flor’s neighbor Reyna Isabel Guzmán heard that her friend was in the hospital. Another neighbor had said she found a tiny premature baby girl out in the cornfield and called the police. They took her to a hospital nearby, where she died several hours later. A police officer said that the fetus matched reports of “suspicious activity” at the Sonsonate hospital. Reyna knew what that meant for Flor. “From the hospital to jail,” she said. “If I had been there, I wouldn’t have let them take her to town, even though she was bleeding to death.”

When I met Reyna, she introduced herself to me as a “human-rights defender.” She is sixty-six, sturdy, and wears T-shirts printed with feminist slogans. Reyna managed to survive El Salvador’s murderous civil war of the Eighties and early Nineties, and when it was over, and a national women’s organization arrived in town, she was the first to join. She invited all her female neighbors, including Flor, to attend meetings at the local branch of the group, Colectiva Feminista. Many would respond, “Let me check with my husband.” Reyna told me with pride that, since she had started running a series of “feminist trainings,” women now attend meetings whether their husbands like it or not, and more have started to use contraception. I asked her how much she is paid for her work. “Nothing, niña,” she answered — Colectiva Feminista covers some of her travel and meals when she is away from home.

On one such trip for the organization, Reyna had heard about a woman a few towns over who had suffered a miscarriage and was then accused of abortion. She sensed that Flor might land in the same trouble. Rumors were burning through the fields where they lived: Flor had tried to abort, people whispered, Flor was a baby killer. Reyna told me, “When one person hears something, the whole town hears it.”

When Flor woke from her coma after several days in the hospital, she protested to the police that she “hadn’t taken anything.” Still, she would be held in detention until the investigation was complete. The police moved Flor from the hospital directly to the Sonsonate bartolina, a concrete jail ringed with barbed wire, to await trial.

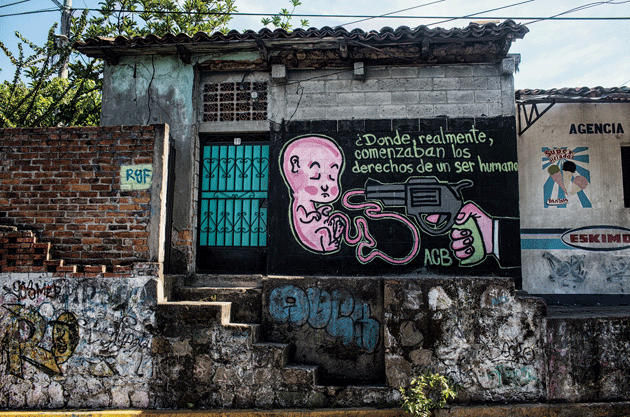

San Salvador’s main public maternity hospital, a drab building of concrete and brick, is situated in the Plaza de la Salud (“Plaza of Health”), across from the general and surgical hospitals. It backs onto a pedestrian walkway lined with benches, stunted trees, and two long gutters full of trash — mostly castoffs from quick meals eaten out of Styrofoam clamshells. Stalls outside the maternity hospital sell everything a patient might need: underwear, girdles, and knit caps to protect against the supposed danger of air entering a woman’s body after she delivers. The old wives’ tale of entrando aire still has a strong hold in El Salvador, so new mothers go home wearing long-sleeved shirts, leggings, socks, slip-on plastic sandals, and even earplugs. Just up the street, office buildings are sprayed with graffiti from the city’s frequent feminist marches: my body is mine and i aborted.

When I arrived at the hospital, a woman in a lab coat at the front desk was swatting at mosquitoes with an electric racket; inside, there were courtyards and open windows. A sign in the large chapel read speaking to jesus eucharist is easier if you turn off your cell phone. Dr. Roberto Águila, the head of gynecology residents, greeted me in his office. He is forty-seven, but has a childlike face. He explained that his job involves training other doctors in how to “manage” a patient who shows signs of having had an abortion.

The current policy is to emphasize doctor–patient confidentiality as a defense against having to report women to the authorities. As a practical matter, Águila said, it can be hard to tell how exactly a pregnancy ended. Some women try home remedies, potions bought at the market, jumping down from chairs, or using ulcer pills known to induce miscarriage — unless a doctor finds a pill partially dissolved in a woman’s vagina, evidence of intent can be difficult to spot. Still, arguments arise with older staff at the hospital, who were trained to call the police at the first possible sign of wrongdoing. Nurses threaten to report doctors for not informing on patients. “Sometimes they scare the residents,” Águila told me. “They get to the bedside and say, ‘You have to denounce her!’ ” The residents come to him for backup. “It’s difficult,” he said. “We have to wait for a generational change.”

I asked whether Zika had complicated matters. So far the hospital had not had any confirmed cases, Águila said, but he had recently seen two babies born with microcephaly. Pregnant women who have a fever or a rash are tested for the virus, yet many of those infected show no symptoms. Águila paused. He wanted me to understand that in many countries with abortion restrictions, when a fetus is found to have Zika-related birth defects, a woman might have the option of ending the pregnancy. “Here it is illegal to interrupt a pregnancy for any reason,” he said.

This is also true for ectopic pregnancies — fertilized eggs that develop outside the uterus and threaten the life of the mother. The standard medical response is a simple surgery to remove the fetus before it grows large enough to rupture an organ, often a fallopian tube, and cause fatal internal bleeding. Ectopic pregnancies are so dangerous that this procedure is allowed even in most conservative Catholic countries, but not in El Salvador. The director of another public maternity hospital explained to me that the nationally approved procedure is to admit the mother and “watch her” until the fallopian tube ruptures, which can be deadly. Only when the fetus no longer has a heartbeat may doctors begin surgery. The director told me proudly that her hospital has seen “zero deaths” as a result of this protocol. “Our women are strong,” she said.

In a famous case from 2013, a woman known as Beatriz requested an abortion on the grounds that her pregnancy threatened her life. She suffered from lupus and kidney failure, and doctors said that the fetus had developed with anencephaly — a condition in which part of the brain is missing — and would not survive. Priests across El Salvador took to their pulpits to preach that Beatriz should carry the baby to term, and the Supreme Court agreed. Beatriz ended up having an emergency caesarean, and the baby did not survive. The story made international headlines but did not put sufficient pressure on the Salvadoran government to reconsider its total abortion ban.

A gynecologist in San Salvador told me that at some public hospitals, including one where she had worked, when doctors find any evidence of birth defects during a sonogram they withhold the information from the patient, lest it tempt her to abort. Expectant mothers might be “feeling the kicks, going out and buying a cradle, planning,” she said, while doctors, nurses, social workers, and the rest of the hospital staff know all along that the fetus is not viable. She recalled one case in which prebirth diagnostics showed clearly that a child would be born without kidneys and would live only a few hours. The mother had no idea until she gave birth, and her doctor requested a ventilator. A nurse got angry, shouting that the hospital had only two ventilators, so why should it waste one on a baby who would not live? (The director of San Salvador’s public maternity hospital denied that it is policy to lie to patients.)

The cemetery in Panchimalco, situated below the Puerta del Diablo, an execution site during the civil war of the 1980s and early 1990s

Toward the end of my conversation with Águila, he volunteered, unprompted, that he had once reported a patient he suspected of having had an abortion. It was 2000, and he was working at a public hospital in Soyapango, a notoriously poor and dangerous part of San Salvador. “A woman arrived at the hospital with lesions,” he said. “I called the prosecutors, and the police came. It was the rule.” He didn’t know if the woman was tried, but she did leave the hospital in police custody, and prosecutors later returned to gather information about her.

“Did you feel comfortable calling the prosecutors?” I asked.

“Of course,” he said. “It was a protocol to follow. We all did the same.”

Upon reflection, Águila went on, “I began to see that the problem has not just a medical aspect but also a social aspect.” What if the woman was the girlfriend of a gang member, or the victim of a rape? Yet he maintained that his decision to report the woman was necessary, given the hospital hierarchy. “If I didn’t comply with a regulation, my boss would have scolded me,” he said.

There are only three lawyers who have built their careers seeking out cases of women accused of abortion in El Salvador. They team up with the Agrupación Ciudadana por la Despenalización del Aborto, or the Citizens’ Association for the Decriminalization of Abortion, an activist group, to provide free legal counsel. The lawyers find out about cases through family or friends of the accused, human-rights workers, or sensationalist newspaper reports about “baby killers.” Many women don’t seek their help, either because they don’t know about it or because of the stigma of the crime. Some of the accused and their families believe that abortion is a sin — those who cannot abide the group’s politics turn away their best chance at exoneration.

Reyna had heard about Agrupación through her work with Colectiva Feminista. As soon as she had learned that Flor was in the hospital, she’d wanted to set off for Sonsonate to see what she could do to help. But there was a problem: her husband said no. “Why stick out your neck for her if she killed the child?” he asked. The rumors about Flor had reached a saturation point, and even Reyna’s two adult children urged her not to get involved. After a few days, she talked them around, insisting that Flor had suffered a natural miscarriage. She got in touch with Agrupación, and the lawyers immediately agreed to take Flor’s case. Depending on whether prosecutors decided to charge her for abortion or for aggravated homicide, Flor faced up to fifty years in prison.

The government of El Salvador does not release statistics on the number of women reported for suspected abortion, or of those tried, sentenced, and incarcerated. A review of available judicial records suggests that from 2000 to 2011, at least 129 women were prosecuted for abortion-related crimes. Twenty-three were convicted of abortion, and nineteen were found guilty of aggravated homicide. Seventeen were put in jail following reported stillbirths or other complications — they became known as Las 17. Agrupación’s lawyers, who work between twenty and thirty cases at a time, say there are probably many more women accused each year than they know about, let alone are able to defend.

In addition to representing clients imprisoned for suspected abortion, Agrupación has provided counsel to women accused of committing infanticide. Smear campaigns abound. La Prensa Gráfica, one of El Salvador’s major dailies, has claimed that Agrupación is funded by trafficking organs to Planned Parenthood. In fact, the organization receives financial support from the Center for Reproductive Rights and Amnesty International. In 2014, when Agrupación was fighting to free Las 17, the head of the government’s Institute for Forensic Medicine went on TV and held up photos of the seventeen fetuses. “Several colleagues have told me to be careful with this issue, it could get you a bad reputation,” a lawyer for Agrupación told me. “It’s the same as defending gang guys.”

There was no need for abortion lawyers before 1998. Until then, El Salvador had laws consistent with its conservative Catholic neighbors: abortion was illegal except if the life of the mother was at risk, the fetus showed serious malformations, or the mother was the victim of rape or incest.

In 1998, the country was still recovering from the horrors of its twelve-year civil war, which had ended six years earlier. A coalition of Marxist guerrillas, center-left groups, and Catholic catechists opposed a ruthless right-wing military government, as U.S. advisers schooled their Central American counterparts on scorched-earth techniques developed in Vietnam and swaddled the army in $1.5 million a day.

The civil war had offered women mostly the same thing as men, pain and death, but those who joined the guerrillas found an impressive array of alternatives to housewifery. Women were commanders, combatants, snipers, radio operators, nurses, and cooks. Pregnancies were discouraged in guerrilla camps, and the fighters were rumored to perform abortions. A former guerrilla named Ana Ayala told a reporter for the Baltimore Sun that, having taken a town, the fighters would stock up on condoms and birth-control pills: “After annihilating the enemy, we went to the pharmacy.”

After peace accords were signed, the umbrella organization of Salvadoran guerrillas — the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, or F.M.L.N. — demobilized its armed units and transitioned into a left-wing political party. They found themselves up against the new archbishop of San Salvador, Fernando Sáenz Lacalle, a member of the conservative group Opus Dei, who publicly campaigned for more restrictive laws, comparing abortion to the Holocaust. In 1997, conservative members of the Legislative Assembly introduced a bill to ban abortion under all circumstances. The F.M.L.N. opposed the bill — women represented a third of its ranks — but the party was outnumbered, and, the following year, the abortion ban became law.

Aside from the Catholic Church, a singular driving force behind the law’s passage was a patrician woman named Julia Regina de Cardenal. After studying in the United States and seeing its culture wars firsthand, she returned home and became president of the Sí a la Vida (“Yes to Life”) Foundation, founded in 1988. As she wrote to me, her foundation lobbied hard alongside the Church:

A team was formed to give information to representatives about the reality of the abortion business and its two victims — the baby who is assassinated in the most cruel fashion, and the woman who runs grave physical and psychological risks.

Sí a la Vida is privately funded — Cardenal is married to the former head of the Salvadoran equivalent of the Chamber of Commerce — and provides abstinence workshops, family training, and “psychological, medical, and spiritual” services to women facing unwanted pregnancies, while defending El Salvador’s abortion laws against any challengers. The organization’s rhetoric is similar to that of antiabortion groups in the United States but has been wildly more successful. To ensure that the 1998 law could not be overturned, Cardenal’s foundation proposed that life be protected “from the very moment of conception” in a constitutional amendment. When the amendment came up for a vote, in 1999, her foundation, along with the Church, gathered more than 500,000 signatures in support, and Cardenal led a group sprinkling holy water in the Assembly chambers. Enough F.M.L.N. members abstained or voted with the right wing to get the amendment passed by a landslide. Antiabortion groups in the United States paid close attention; a leader in the movement called El Salvador “an inspiration.”

Abigail Sanches, from San Luis Talpa, La Paz, in an examination room at a maternal waiting house, Planes de Renderos. Women without close access to hospitals come to these facilities to wait out the end of their pregnancies

The Zika virus presents the first serious challenge to antiabortion activists and the Catholic Church, as Agrupación and other groups have tried to use it as a wedge to reopen discussions about the law. They are hoping for a shift in public opinion similar to the one in the United States in the Sixties, following a grisly epidemic of rubella, which caused microcephaly and deafness in newborns. People became more tolerant of abortion, and this is believed to have helped secure the ruling in Roe v. Wade. In February, Pope Francis seemed to give an opening, as he suggested that birth control could be used in countries affected by Zika, saying, “Avoiding pregnancy is not an absolute evil.” But when asked whether, in this scenario, abortion could be considered a “lesser evil,” the Pope declared, “Abortion isn’t a lesser evil, it’s a crime. Taking one life to save another, that’s what the mafia does. It’s a crime. It’s an absolute evil.” Human Life International, an antiabortion network affiliated with Sí a la Vida, responded with a statement reaffirming the “absolute immorality” of birth control.

But most Salvadorans feel otherwise. Even before the onset of Zika, Catholics in Latin America were known to diverge from the Vatican on certain points, picking and choosing which principles to follow. In El Salvador, the Church’s ban on abortion is upheld to the extreme, even as the government has — to the disappointment of fundamentalists — systematically ignored its advice on contraception. By law, free condoms and temporary sterilizing injections are to be distributed at health centers, no questions asked. Bananaflavored condoms are available in the checkout lines at grocery stores for those bold and well-off enough to buy them: a box of three costs $1.25, more than lunch. There are some barriers to access: one activist told me that teenage girls are often turned away and told they are too young, even though a third of the country’s pregnancies are among girls under the age of nineteen. When I stopped in at a Farmacia San Nicolás, a chain with more than fifty branches around the country, I asked for a box of condoms, and the cashier handed me a flyer with a graphic of a condom wrapper containing two interlocking wedding rings.

The only person with actual power to revisit El Salvador’s draconian laws is Lorena Peña, a former guerrilla fighter and F.M.L.N. leader — and avowed feminist — who is now the president of Congress. In her memoir, Peña recalls having to take time off from the civil war to give birth to her second child. She airily acknowledges the options open to her, writing that she decided not to terminate her pregnancy because if she didn’t have her second child then, she might never have had another opportunity. Peña has acknowledged the work of groups like Agrupación, saying in 2014, “There is a network of women working on the issue of abortion, and we support them.” But last year, she walked that back. “Look, I think the constitution is clear in prohibiting abortions,” she said. “And discussion of decriminalizing abortion is not on the F.M.L.N.’s agenda. I think it is fundamental to provide better sex education for women and men to avoid unwanted pregnancies.”

Peña’s public position may better reflect political calculation than personal belief, but even Zika has not made her budge. “She has shared informally that she is disposed to open the debate,” longtime feminist activist Dalia Martínez told me. “But for now the discussion is closed.”

My first morning in San Salvador, I read a report in the newspaper about a baker’s difficulties finding a job. The man, who had years of experience, had responded to an ad that gave the bakery’s hours and phone number but omitted the most crucial piece of information: Which gang controlled the neighborhood? Was it Mara Salvatrucha, known locally as the Letters, or Barrio 18, the Numbers?

Invisible lines divide the capital. San Salvador is a hot and hazy city of concrete houses, barbed wire, shacks, and air-conditioned shopping malls sprawled out at the base of a stubby volcano. Most people use the same landmark to orient themselves: a big statue of Christ known as “El Salvador del Mundo” (“Savior of the World”), which presides over a traffic roundabout. “Above Salvador” is where the rich people live, in gated communities built up the side of the volcano. The baker lived “below Salvador,” where the Letters and Numbers divide territory. There are no checkpoints — control is complex and subtle — but even those who are not affiliated with either gang are painfully aware of which runs their neighborhood, and of the possibility that if they set foot in the wrong place they could end up killed. This is how bus commutes that should be ten minutes become forty-five-minute trips to take the long way around — just in case. The police are rumored to have a map of El Salvador with all the invisible lines clearly drawn. If it exists, they keep it to themselves. Eduardo Halfon, a Guatemalan novelist, has described the constant calculation of risk as a “normal, everyday psychotic state.”

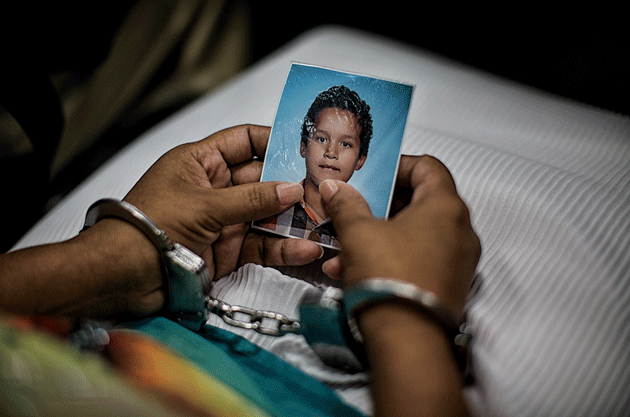

At a hearing to reduce her sentence, in San Salvador, María Teresa Rivera holds a picture of her son, Oscar, who was six when she went to prison. She had already served four and a half years in jail for aggravated homicide of her prematurely born infant

The baker, who lived in Letters territory, was relieved to learn that the bakery was in Letters territory, too. Still, to get the job, the newspaper reported, “He had to handle two interviews: one with the owner of the establishment and another with the local head of the gang.” The gang leader asked him for his I.D., to check his home address and see to his satisfaction that the baker wasn’t a policeman or a spy from a rival gang. In the end, the baker was hired, so long as he agreed to teach two kids who help out the gang how to bake bread.

Before my arrival, El Salvador overtook Honduras as the murder capital of the world. More Salvadorans were killed in 2015 than in any year during the civil war. A young woman told me that she was “lucky” to have seen only a few bodies on the street. Femicide is now a leading cause of death for women. Sometimes, women join up with gangs for protection, or else to make money or to be part of the scene. A young woman named Medea told Juan José Martínez, a Salvadoran anthropologist who studies gangs, that women have two choices for initiation: to be beaten brutally or to have sex with all the members of the group. Medea chose the beating. She explained that, when gang girls are raped, “afterward the homeboys don’t respect them.” Martínez notes the “diabolical sarcasm” of gangs, which call rape “initiation through love.” Medea described one such initiation in which her husband participated:

They all got over her. They did everything to her, at least thirty got on her. . . . The girl called me and said she couldn’t bear it anymore, she was hurting, so I told them, “Hey, guys, enough already, leave her,” but they didn’t pay any attention. . . . They did everything to her, and when I say everything I mean everything. When I went to see her at the end she was a rag.

Murder makes headlines, but rape does not. Gang members rape one another’s girlfriends or sisters as revenge or punishment, and initiate new boys by finding a woman or girl for them to rape — perhaps together, to really feel close. Or they will rape simply because they are in control of whole city blocks and they can. The commonly cited number is that five Salvadoran women are raped per day, but those are only the reported cases. Indeed, rape is so common that, were there an abortion-law provision for victims, it is easy to imagine that a substantial proportion of pregnant women and girls would qualify.

In this atmosphere, El Salvador’s official response to Zika seemed delusional, if not insulting. In January, after the number of registered cases rose to more than 4,000, Eduardo Espinoza, the deputy minister for health policy, announced: “We are recommending to women of fertile age that they take precautions to plan their pregnancies, and avoid getting pregnant this year and next year.” Many countries have suggested that women delay pregnancy because of Zika, but until Espinoza’s announcement, no government had flatly told women not to get pregnant for a couple of years, not even during the rubella or AIDS epidemics.

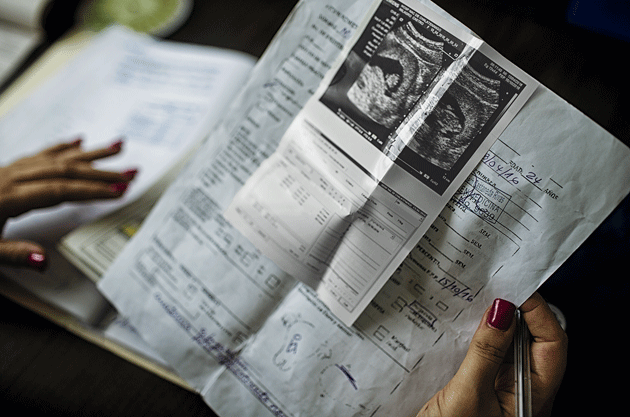

An ultrasound photograph of Milagro Castro, a twenty-four-year-old woman who is almost five months pregnant, San Luis del Carmen, Chalatenango. She contracted the Zika virus in her first trimester

I met Espinoza in his office downtown, a short walk from the Plaza de la Salud. All expansiveness and geniality, he stood by the government’s message, insisting that building up herd immunity is the answer. “It may seem extreme in the context of Latin America, but not for us,” he told me. Mosquito-borne chikungunya infected some 17,000 people in El Salvador in a single week in 2014. Zika appeared for the first time in November 2015, and the government feared that the virus curve could look similar. Espinoza was well aware of the nightmare scenarios, and explained that El Salvador doesn’t have the money to deal with babies born with microcephaly, who “enslave their mothers.” The health ministry’s Zika program also includes fumigations, although these have run into trouble when gang members refuse entry to certain neighborhoods. Espinoza conceded that asking women not to get pregnant for two years was a controversial move. “It was a recommendation, right? We can’t tell people not to have relations.”

Espinoza told me that he feels considerable pressure from his North American counterparts to control the spread of Zika. But even as the number of infections in the United States climbed to more than 6,400, Congress provided no funding to combat the virus domestically or abroad. In June, House Republicans proposed such a bill, but it was $800 million short of the $1.9 billion President Obama had requested, and it contained provisions limiting the distribution of contraceptives and blocking Planned Parenthood from providing services. Congress broke for summer recess before approving a relief bill of any kind. Meanwhile, the number of babies worldwide born with microcephaly as a result of the virus reached 1,500, and the New England Journal of Medicine reported a dramatic rise in the number of women seeking abortions in Zika-affected countries, including El Salvador.

Zika poses yet another possible threat to Salvadoran women, because there is some evidence that infection may increase the probability of miscarriage. Nelson Menjivar, a gynecologist in San Salvador, told me that he saw an increase in miscarriages and stillbirths after the disease arrived. The mothers were young, “the healthiest in the world,” he said, so he was puzzled. “I saw three stillbirths in the same afternoon.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said there is no concrete proof that Zika can cause miscarriage, but scientists there are studying a possible link. Espinoza acknowledged that there could be difficulty in differentiating illegal activity from tragic loss. “Many abortions are miscarriages, abortions that aren’t induced,” he said. (The term for “miscarriage” in Spanish is aborto espontáneo.) “Here, that is punished. There are women in prison. We have the perception that surely many of these women are unjustly in jail.”

The two lawyers on Flor’s case, Daniela Ramos and Dennis Muñoz, share a passing resemblance, with round faces and wavy hair, and they’ve started to think of each other as siblings. They call each other by the same nickname, “Crudi,” short for “crude and direct.” Daniela croons into her phone, “Crudi, where are you?” Dennis is always late.

I met up with them at Agrupación’s office, a nondescript building in downtown San Salvador that houses three women’s organizations. The only sign out front reads casa de todas (“House of All Women”). It was the day of Flor’s trial. As I entered, I passed through a badly lit reception area that led out to a small patio decorated with plants. The rest of the office looked like someone’s basement: stacks of filing cabinets among scattered televisions and bags and backpacks. Daniela was there, eating a quick breakfast of rolls with beans and cream. She and I watched for Dennis’s arrival on an old TV showing split-screen security-camera footage. When he finally appeared, we piled into his car and set off for the courthouse in Sonsonate, an hour’s drive away. Daniela carefully layered on her makeup while Dennis filled us in on the good news and the bad news.

Idalia Alverado Sanchez and her husband, Alex, await the birth of their first child at a maternal waiting house, Planes de Renderos. Idalia is twenty-one and has two other children. She had her first when she was thirteen

The good news was that the previous month a judge had granted Flor “alternative measures,” allowing her release from jail if she periodically confirmed her whereabouts with the police. This was likely because she had solid lawyers from the beginning. Most of Agrupación’s other cases are taken over from public defenders who may take a dim view of clients accused of abortion or are simply too overloaded to mount a proper defense. Dennis was hopeful that the judge understood that there was no evidence of anything other than a natural miscarriage. Still, he cautioned, “Anything could happen today.”

The night before, I’d reviewed a study by Jocelyn Viterna, a sociologist at Harvard, and José Santos Guardado Bautista, a Salvadoran lawyer, who analyzed the cases of Las 17. It was not encouraging. They found that “at every stage of the judicial process, the state aggressively pursued the mother’s prosecution instead of pursuing the truth.” Police gathered only evidence that would incriminate the women, and let neighbors and employers do the work of presenting exculpatory information, “thus contaminating both the scene of the crime and the credibility of the interviews.” Doctors regularly failed to investigate likely birth complications, forensic specialists used outdated tests, and judges often argued in their sentences that women should know instinctively how to take care of their pregnancies and children — even when they are hemorrhaging. Viterna and Bautista write, “Women, who appear to have been guilty of nothing more than suffering an obstetrical emergency, are accused of aggravated homicide simply because, as mothers, they should have done more to prevent the infant’s death.”

The bad news, Dennis said, was that they had a new case, a girl from a rural area in central El Salvador. Same story as Flor’s — a miscarriage, accused of abortion — plus this time it was rape. Dennis had visited her in prison. “She’s doing badly,” he said. “Really badly.”

“A la puerca . . . ” Daniela breathed out the genteel curse. Of the twenty-five or so women Agrupación was currently defending, five had been raped by gang members, and two had been raped by members of their family. None had reported the assaults to the police, out of fear of retaliation. Even if they had, Dennis told me that it was a bad idea to present rape as evidence at trial, in case a judge viewed rape as a motive for abortion.

When we got to the courthouse, Flor was waiting outside, sitting in a plastic chair next to two teenage gang members in prison whites. One had a Letters tattoo across his forehead, and the other was giggling inanely, as if he were high. Flor ignored both. She’s a diminutive woman, with skinny legs and a stomach slightly puffed out from malnutrition. She has a lovely smile, though she flashes it rarely. Daniela fussed over some sunspots on her cheeks and forehead, insisting that she go to the health center for ointment if they itched. Flor told me that she got the spots after leaving jail, since she was so pale. “In there you don’t get any sun,” she said. She also had aches in her legs after nine months of confinement. Yet she seemed more dazed than angry. The jail was one big room shared by five dozen women where she couldn’t move around, Flor said, but there were three full meals a day. Though most women slept on the floor, a kind fellow inmate had gifted her a hammock.

When the judge and prosecutors arrived, at noon, the trial commenced. Dennis’s style of argumentation was rather theatrical: he stabbed at the air as he explained that natural miscarriages were not against the law in El Salvador, only aborto consentido y propio (“intentionally induced abortions”). There was no evidence that Flor had induced an abortion on purpose, he said. Daniela flipped through a book of the relevant penal codes, and she occasionally pounded on a page to get Dennis’s attention when she thought he was missing something.

Flor Arely Sánchez at home with her daughter María de los Ángeles, a week after she was acquitted of homicide, San Julián, Sonsonate

The prosecutor countered that Flor must have induced an abortion intentionally, perhaps with pills. Prosecutors in these cases are often women, and this one had a twitchy way of pacing the courtroom as if she thought she was in a TV drama. She was joined by a representative from a special division of the prosecutor’s office responsible for crimes against minors and women. He gave a long presentation “on behalf of the rights of the dead fetus.” He said that the case “should be a warning to those looking to hurt children. I am struck by the fact that she didn’t have the instinct to protect her baby.” (During a break, Daniela hissed, “How was she supposed to have a maternal instinct when she was knocked out on the ground?”)

The only witness called was the policeman who had investigated the fetus found in the cornfield and connected it with Flor’s trip to the hospital in Sonsonate. He showed up out of uniform and removed a white baseball hat before testifying that he’d cuffed Flor to her hospital bed. The prosecutor asked the judge for the maximum sentence.

Flor was impassive, but she had a scrap of blank paper rolled up between her fingers and rubbed it continuously against her leg. After closing statements by both sides, at four o’clock the judge ordered a final break while he deliberated. We filed out of the air-conditioned courtroom into the afternoon humidity.

Dennis and Daniela wandered off to buy a Coke, leaving me alone with Flor. I offered her some water, which she declined, saying it would only make her have to go to the bathroom. We leaned against the tinted glass panes of the courthouse wall, sweating. Fifteen minutes stretched to half an hour. It struck me that I had met her on the most critical day of her life, and I had no idea what to say. What could I say to someone who faced up to fifty years in prison for no good reason?

One of the guards — there had been three in the courtroom, all armed — wandered over to us. He was fat and wore a black cap. “She’s going to be acquitted,” he said. “She’s going to go free today.”

I looked at him. Flor didn’t look up.

“It’s her lucky day,” he said, pointing at her. “We all make mistakes.” Then he asked her, “Was it a boy or a girl?”

“Girl,” she said, still looking at the ground.

“And she died in the hospital?”

“Yes.”

We stood in silence for some time before the judge called us back into the courtroom, where he read out the verdict: for lack of evidence, the defendant was acquitted. Dennis leaned across Daniela, placed his hand on Flor’s shoulder, and repeated the message: “You’re free.”

The national women’s prison is in Ilopango, a part of the capital that is decidedly “below Salvador.” I accompanied Dennis there to visit a few of his clients. Other visitors formed a line along the prison fence, most of them carrying clear plastic bags filled with chopped vegetables and rolls of toilet paper. Dennis wrote out the names of all the women he wished to see, but it was up to the guard to choose who would be allowed out to the exterior courtyard to speak with us. Dennis has visited the prison for eleven years, and he has only twice been allowed inside, to a courtyard behind the walls. He remembers terrible heat, the smell of too many bodies together, and the noise of too many voices bouncing off concrete. Women spread out towels to sit there all day, hoping to get some air. They sleep at least seven to a cell designed for two people: two deep in twin bunk beds and three or four on mattresses on the floor.

The first woman to come out was María Teresa Rivera. Her long curly hair was still damp from the morning shower, and she wore a knee-length white skirt and a blue T-shirt printed with a butterfly. She is thirty-three, with a beautiful wide face, completely bare of any makeup — unusual for a Salvadoran woman, even in prison. María Teresa holds the record for the longest sentence for abortion-related crimes in El Salvador: forty years, for aggravated homicide. She told me that one November day, in 2011, she had felt sick, so she went to the outhouse, felt a “little ball” escape her body, and began hemorrhaging blood. Her mother-in-law found her and called an ambulance to take her to the nearest public hospital, where doctors found a ripped umbilical cord and alerted the police. She had been in prison for four and a half years, and had only seen her eleven-year-old son, Oscar, a few times. Now she was up for a hearing on reducing her sentence, which was scheduled for the following day.

María de los Ángeles walks along the path on which her family carried Flor after she prematurely gave birth, San Julián, Sonsonate

When María Teresa first got to prison, she hadn’t been aware that there were other women in the same situation. “I didn’t know anything,” she told me. “I never looked at the newspaper.” But now they seek one another out. “We are always discriminated against because of the crime for which we were convicted. Some of the women have gotten hit. Or called bad words. They yell at us.” Comeniños (“baby eater”), is a popular attack.

María Teresa turned to Dennis. “There’s a new girl, eighteen years old.” It was Ana, the new client Dennis had mentioned to Daniela in the car. By chance she was the only other prisoner allowed out to meet with us, so we pulled up an extra chair. Ana is childish, cute, with a round nose. Her eyes were outlined in eyeliner, and her hair was up in a high wispy ponytail. She was wearing a pink T-shirt, jeans, and white flip-flops printed with flowers. By way of introduction I asked her how she had ended up in prison, and she burst into tears.

Once she recovered, Ana told her story with a smile, as if it were the most normal thing in the world. She was sixteen when she met a boy in school. He was younger, fifteen, and he liked her. He was in a gang, but low level, and she knew plenty of people in gangs, so that was okay. The boy wore the Letters’ usual long-sleeved shirts even though he didn’t have any tattoos to cover. Mostly he just got together with his friends to make sure that the Numbers didn’t enter their territory.

Ana went out with the boy for about a year, and then he told her that he wanted her to come to his house so they could be alone. She didn’t want to, and anyway they didn’t have any condoms. She said no, and he started to threaten her. He said that if she didn’t come, he would send someone to kill her.

He didn’t have a gun, as far as she knew, but she was scared. He was serious. He’d even mentioned talking to her mother to see if they could live together, and when she told him she didn’t want to, he got very angry. She tried to break up with him, to say that it was over, but he threatened again to have her killed.

So Ana started going to his house regularly, leaving home at 6:30 in the morning, when she’d usually head to school for her first class. Her parents didn’t know. The boy lived a few towns over, and by the time she arrived, his mother already would have left for work. His sister would go over to a neighbor’s place so that he could have the house to himself and do what he wanted with Ana. Afterward she would get to school late. This went on for several months, until the boy abruptly decided to join the military and went to live in the barracks. Ana had no idea that she was pregnant. She still bled from time to time, and thought it was her period.

Her high-school class had started out with twenty-five students, twelve of them boys. By the third year, only four boys remained. The rest had dropped out to join gangs. Of her female classmates, Ana said, “Only three of us went out with gang guys.” Had the others been threatened, too? “No, I think it was just me.” (As Ana told me about the gangs in detail, Dennis pointed out that talking like this could get her killed should she be released from prison. I have changed her name.)

One day, this past April, Ana started to feel ill. She went to the outhouse, and suddenly blood was everywhere. Ana’s mother and grandmother called an ambulance, which took her to a nearby public hospital. She passed out during the ride. Doctors said that she had given birth and called the prosecutors. They got in touch with Ana’s mother, who gave them permission to search the house. The police found a fetus in the latrine. Forensic specialists ruled the cause of death “undetermined.”

“When I woke up in the hospital I saw the policewoman,” Ana told me. “One was always watching me, all night.” She spent two days in the hospital. “I was surprised. I had my period and I hadn’t grown at all.” At first, doctors said that she had likely been five months pregnant, for which she would have faced prosecution for abortion. Later, the estimate was changed to eight months — increasing the likelihood that she could be charged with aggravated homicide. “They said to me that I had taken something, that I had done it,” Ana said.

When Ana arrived at Ilopango, the inmate in charge of her dormitory advised her to lie to the other prisoners about why she was there. “The prisoner who is in charge of where we sleep told me not to say, that they would want to hit me,” Ana said. “Better tell them it was for drugs. Most people are in for that.” She told the other women she was part of a gang. Ana faces a sentence as long as María Teresa’s, or even longer. If she were to be released, she has nowhere to go but home. I asked her if she was afraid of returning to live among the gangs, or of seeing the boy again were he to come back from the military. She replied, “Just to go home would be so wonderful.”

When a prison guard came by and told María Teresa that she had to go back inside, she stood and wrapped the girl in a hug. Ana whispered into her hair, “Good luck.”

After Flor’s trial, we emerged from the courthouse and saw more than twenty people advancing up a dirt road: kids, old people, teenagers carrying babies. This was Flor’s extended family, her three daughters and two sons, her mother, nephews, siblings, and a grandson who had been born the previous month. They had been waiting outside for hours. Daniela called out, “Acquitted!” and the first person to reach Flor and embrace her was Reyna. Flor’s face, which had remained frozen, finally cracked, and she cried into Reyna’s shoulder.

Someone had rented a beat-up blue pickup to take the whole group to Sonsonate for the day, and now they retreated down the road toward the truck. Flor said a quick goodbye to the lawyers. Then she and the others hauled in, all of them standing on the flatbed. It was a forty-five-minute ride home, and they stopped in town along the way. “We couldn’t have a party because of the economics of it,” Reyna said. “So we got together in church and raised a prayer.”

A week later, I visited Flor and her family at home up on the mountain. It is a peaceful if poor part of El Salvador, with little gang presence, and the house is surrounded by banana, mango, and lime trees. Flor was still worn and underfed, but she looked at least five years younger than she had on the day of her trial. We sat on the porch and laughed when the mangoes fell off their branches and thwacked against the sheet-metal roof, making everyone jump. Before she went to jail, Flor had been the only one in her family with a steady income; she’d been cleaning and doing laundry for a woman in town. Now her neighbors took up collections for the family, putting together packets of sugar and soap. Flor said that she wanted to return to work, but her legs still ached from her time in jail, and she wanted to wait until walking was easier. Obidio told me privately that the experience in prison had changed his sister. “She’s more afraid,” he said. “She feels like a failure.”

We talked about the events of the past year, and how lucky a coincidence it was that Reyna lives nearby. “If no one realizes, nothing happens,” Reyna said. “Agrupación is there, on call, but if no one coordinates and informs them, no one will realize that anything is wrong.”

Flor still seemed dazed. By then, I’d seen María Teresa, too, have her sentence annulled for lack of evidence. I attended her trial, in part because Dennis and Daniela suspected that my presence at Flor’s may have affected the outcome. Afterward, the prosecutor announced that she would appeal. Ana is still in prison awaiting her court date. Both women could end up in prison for decades. And the judicial cycle would continue, over and over again.