When Utinan Won was twelve, he liked to sprawl out on the floor of his living room and read manga. His favorite series was Naruto, the story of a lonely orphan. Naruto, who also happens to be twelve, has spiky yellow hair and dreams of becoming a ninja, but he is forced from his village after his neighbors learn that he has a mystical fox inside him — a source of ominous power.

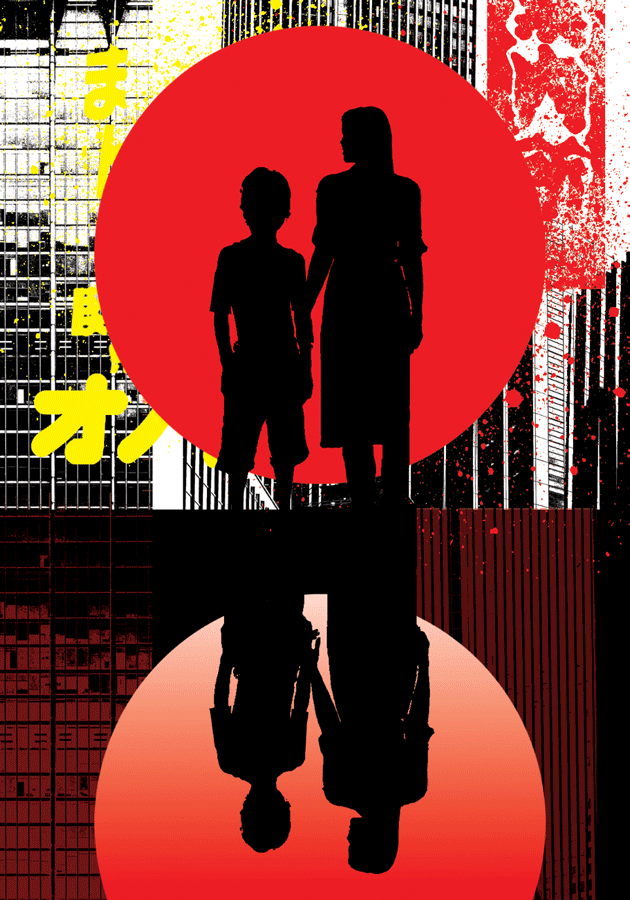

In those days, Utinan and his mother, Lonsan Phaphakdee, lived just outside Kofu, a small but bustling city two hours west of Tokyo, where neon billboards flash against a backdrop of green hills. Utinan rarely went outside, but on weekends, the kids from his neighborhood would tell him about their classes, school plays, and soccer games. He was envious. He had never been allowed to join them in school, because he was an undocumented immigrant.

Lonsan had come to Japan from Thailand in 1995, after a chatty recruiter showed up in her village and offered her a job at a restaurant. She was living with her parents, who had no money or property, and the recruiter offered to pay for her plane ticket. When she arrived at the airport in Tokyo, she was given a visa that allowed her to stay in the country for seventy-two hours. Then she was met by a different recruiter, who informed her that she owed him 3.8 million yen — nearly $40,000 — and that she’d have to start paying off her debt. Lonsan was terrified, but followed him to his car. He confiscated her passport and took her to a brothel. She worked there for two years, until she paid back her debts and fled to Kofu, where a friend of hers lived. Later she heard that the brothel was raided by police, but no one came looking for her.

Lonsan was free, but she lacked both the legal documentation to remain in the country and the money to return home. In Kofu, she met a Thai man who had also overstayed his visa. The two of them briefly dated, and she became pregnant. Weeks after Utinan was born, the man was discovered by the police and deported back to Thailand. Lonsan never heard from him again.

Citizenship in Japan is jus sanguinis — determined by blood, rather than by place of birth. Though Utinan qualified for Thai citizenship, Lonsan didn’t know how to register his birth from abroad, so he was rendered stateless. Until 2012, immigrants in Japan applied to their regional government for identification cards, which allowed them to access public resources, including schools, and local authorities sometimes turned a blind eye toward undocumented residents. Lonsan, however, was too scared to get I.D.’s for herself and Utinan — the risk of being reported to the same officers who had deported her boyfriend loomed too great. Five years ago, Japan created a new residency-management system that centralized oversight of foreigners, requiring all immigrants to procure a national I.D. card. For people without the right papers, any encounter in a hospital, school, or government office became perilous.

Before Utinan turned twelve, he and Lonsan changed apartments frequently, so immigration officers couldn’t find them. They moved between suburbs, went to Nagano — a larger city to the north — and then back to Kofu. Shunji Yamazaki, a longtime immigration activist, had friends in the area’s Thai community and heard rumors about a child who had never gone to school. Shortly after Utinan’s twelfth birthday, Yamazaki tracked him down and invited him to take courses at Oasis, a nonprofit he’d founded to provide tutoring, legal services, and meeting spaces to local immigrants.

There were six other children in Utinan’s class. They all needed help with their Japanese, but their parents — who came from China, Korea, Indonesia, and Brazil — had visas, and the kids had grown up attending Japanese schools. Utinan was the only undocumented student. He was gangly and shy, with shaggy hair that he was always brushing away from his eyes. He couldn’t figure out what to talk about with his peers. He wasn’t even sure how to introduce himself. His mother called him by the nickname Sifa, but he wanted something that seemed more Japanese. His complexion, lighter than Lonsan’s, might let him pass. He knew that his father’s last name was Wuthipang, so he landed on a Japanese-sounding version: Utinan, a name of his own making.

To help Utinan socialize, Yamazaki arranged for him to eat lunch at a local junior-high school. There were assigned seats in the cafeteria. “I had to sit in front of a girl,” Utinan told me. “I couldn’t look at her face.” For the first week, he sat in complete silence as he picked at his rice. Eventually he lifted his eyes to meet hers, and managed to blurt out, “Can I borrow your eraser?”

Yamazaki urged Utinan and his mother to apply for legal status. If they were denied, he’d find them a top-notch lawyer to appeal the decision. It was a big gamble, but Yamazaki believed that their case was strong. Lonsan couldn’t read Japanese, but Utinan had learned it quickly — he cannot read or write Thai — and any judge, Yamazaki thought, would surely sympathize with Lonsan’s plight as a victim of human trafficking. After they applied for residency, they could stop living in hiding while they awaited the government’s decision. Utinan could register for junior high at a regular school, and Lonsan, who had a seasonal job picking fruit, would have an alibi if immigration police ever raided the orchard where she worked.

In July 2013, Lonsan and Utinan, then thirteen, borrowed a friend’s car and traveled eighty miles east to the Immigration Bureau in Tokyo, to surrender. At ten in the morning, they arrived at a tall steel-and-glass building and found seats in an empty waiting room facing an array of intimidating signs. Utinan tried to translate the Japanese for his mother, but the messages had too much bureaucratic jargon he didn’t understand. Hours passed. They didn’t know when their names might be called, so they were afraid to use the bathroom or buy a snack from the 7-Eleven downstairs. Late in the afternoon, they were summoned into separate interrogation rooms, where, Utinan recalled, an official explained to him that the Justice Ministry would make a decision about their deportation within a year. The official also said other things, but Utinan was too nervous to listen. By the time he and his mother were dismissed it was nearly ten, and they didn’t get home until after midnight.

In 1853, during a period of Western conquest of new markets, Matthew Perry, a U.S. naval commodore, sailed into Tokyo’s harbor with a fleet of warships, expecting a trade treaty. Japan had no navy of its own, and when the shogun — the general — was forced to concede to American demands, many of his countrymen viewed the acquiescence as a humiliating defeat. A movement, backed by samurai leaders, quickly rose to oust him. Its slogan, “Sonno joi” (“Revere the emperor, expel the barbarians”), expressed the idea that outsiders undermine Japanese strength and became a catalyzing philosophy of the new Japanese Empire. In 1863, Emperor Komei passed the Order to Expel Barbarians, which inspired a spree of attacks on foreigners.

Modern Japanese politicians echo sonno joi by advocating racial purity. “There are things Americans have not been able to achieve because of multiple nationalities,” Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone declared in 1986. “On the contrary, things are easier in Japan because we are a homogeneous society.” Shinzo Abe, the current prime minister, backs tough restrictions on immigration, because he considers it to be destabilizing. “In countries that have accepted immigration, there has been a lot of friction, a lot of unhappiness both for the newcomers and the people who already lived there,” he said in a 2014 television interview. This is likely the only time that Abe has even uttered the word “immigration” in public since he was elected in 2012. When asked about the subject, he usually responds with a discussion of “foreign workers,” as though immigration’s only conceivable form were a temporary labor arrangement.

About 2 percent of Japan’s residents are foreign-born, which is extremely few for an industrialized country. (In the United States, by comparison, immigrants make up 14 percent of the population.) The paucity of foreign citizens was ensured by law: after World War II, the country ratified a new, American-drafted constitution, and shortly after, the Nationality Act legally mandated citizenship by blood, stripping all colonial subjects of their Japanese status. A person could be a citizen only if his or her father was Japanese — mothers didn’t count.

At the time, more than 2 million Koreans who had been forced at the start of the war to work in Japan’s coal mines, shipyards, and factories lived on the mainland; they constituted the country’s largest foreign group. Under the Nationality Act, they had no voting rights, they could not hold government jobs, and police were instructed to closely monitor their communities. “They are not included in the term ‘Japanese’ as used in this directive,” a law-enforcement memo from 1945 explains, “but they have been Japanese subjects and may be treated by you, in case of necessity, as enemy nationals.” More than 600,000 Koreans remained in Japan, stranded in a second-class existence. They and their children are now, in the words of Erin Aeran Chung, the director of the Racism, Immigration, and Citizenship Program at Johns Hopkins University, a “highly assimilated, legally foreign community.”

In 1985, following international pressure, the Nationality Act was revised to allow Japanese mothers to pass citizenship to their children. A few years later, the country’s manufacturing sector was experiencing a labor shortage, and the government decided to fill the empty jobs by further loosening its restrictions, this time for members of the diaspora. The grandchildren or great-grandchildren of Japanese farmers who had gone in the late nineteenth century to search for gold in Peru or left a few decades later to work on coffee plantations in Brazil were invited to return as permanent residents. Many settled in cities along Japan’s industrial corridor, like Hamamatsu and Toyota. “There were suddenly large groups of foreigners in the streets,” Yasuyuki Kitawaki, a former mayor of Hamamatsu, told me. To this day, these residents are still not counted as citizens in the national census.

As this population was arriving, a literary cottage industry called nihonjinron (“the theory of Japaneseness”) began to flourish. The genre, a blend of anthropology, pop psychology, and management theory, attributed the superiority of the Japanese people to a national character of collectivism, a strong work ethic, and a minimalist aesthetic. Doing things the “Japanese way,” these books argued, was always best. And their success was ultimately based on race — literally, “Japanese blood.”

Yet not even Japanese excellence could insulate the country from economic disaster. In 1990, the stock and real-estate markets collapsed. Desperation and bitterness gave way to a proliferation of angry nationalist rallies, which have continued to the present day. Protesters took to gathering in the streets and harassing ethnic minorities, whom they accuse of taking away their jobs. Koichi Nakano, a political scientist who studies these groups at Sophia University, in Tokyo, told me, “These are basically spontaneous, rather fluid networks of haters.” Most are working-age men who have never managed to find secure employment; Nakano said that 37 percent of Japanese workers today have sporadic, temporary positions.

When I was in Tokyo, not long ago, on any given day I would see dozens of people carrying Japanese flags and shouting vague, violent threats in minority neighborhoods or outside foreign embassies. Nakano estimates that there are more than a hundred nationalist groups that convene across the country. They are not on the fringe: A leader of the group Zaitokukai, which has called for a large-scale massacre of Korean residents, has been photographed hobnobbing with a senior member of the Liberal Democratic Party, the current ruling party. Several L.D.P. officials have been photographed posing with the head of a neo-Nazi group in front of a Japanese flag. Even the more centrist members of the L.D.P. proudly refer to their country’s ethnic makeup as “homogeneous” — an impossible claim to make of a former colonial empire. Nearly half of Abe’s cabinet belongs to a group known as the League for Going to Worship Together at Yasukuni, a shrine in Tokyo that commemorates Japanese soldiers, including a number of convicted war criminals. Abe’s wife makes pilgrimages to Yasukuni, and Abe sends offerings on holidays.

One afternoon, I attended a festival at the Yasukuni Shrine. The entrance was lined with tens of thousands of paper lanterns emitting a warm, golden light. Visitors wandered around eating vanilla soft serve. I asked a man why the festival was so important to him. “Koreans!” he said, and thrust his middle finger into the air. “Fuck Chinese!” He wore a shirt with a Japanese flag and text that read japanese! be proud! you are the descendants of the yamato race.

In August 2014, a year after Utinan and Lonsan surrendered, they received a call from the Justice Ministry. At last, they thought. Utinan had spent the past year at a regular school and was about to graduate from eighth grade. He played on the basketball team and was a member of the drama club — in the latest production he’d been cast as a man who travels through time to find his lover. He was doing well in all his classes, particularly math. He felt Japanese.

Utinan answered the phone. The official on the other end — Utinan never caught his name — said that he and his mother were being deported. He was brief, matter-of-fact: they had to go. Utinan was stunned. He called Yamazaki, who told him that they’d have to file a lawsuit to appeal the decision. “Are you ready to fight the authorities?” Yamazaki asked.

“Yes,” Utinan replied.

First, Yamazaki advised, “You need the community’s support.”

At school, Utinan dutifully asked for permission to address his classmates. One Wednesday at the end of a choir rehearsal, his teacher summoned him to the front. He took a deep breath and began to tell everyone his story, of his desire to belong. When I asked Utinan how he felt coming out to his peers, he said, “I wanted to tell the truth to everybody, whatever the outcome might be.”

The other children were shocked. A few girls cried. They hadn’t heard of a situation like Utinan’s before; there weren’t many foreigners at their school. Some in the class had simply assumed that everyone in Japan was Japanese.

On a rainy morning in July 2015, Utinan, Lonsan, Yamazaki, and twenty supporters — mostly class moms — caught a bus at five in the morning to attend a hearing at the Tokyo District Court. School was still in session, which meant that Utinan’s peers weren’t able to attend themselves. Lonsan, unlike her son, didn’t feel comfortable soliciting the community’s support or speaking to journalists (including me), so it became — on Facebook, and in the Japanese press — “Utinan’s case.”

In the courthouse lobby, the group stood in a huddle, waiting for their attorney to arrive. (I had been permitted to join them only after passing a written test on Japanese immigration law, courtesy of Yamazaki.) Utinan wore a white shirt and black slacks that hung loose over his narrow frame. He fiddled with his shirt buttons, but his eyes looked hopeful, and he had a wide, distracted smile fixed on his face. He kept giggling nervously, though he told me that he was ready for the hearing to begin. Yamazaki, bald and brittle-looking, with an arched spine, stood with his hand on the boy’s shoulder.

Utinan’s lawyer, Koichi Kodama, was running late. He hurried over to greet us, tucking away his iPhone into his suit pocket, and bowed to his clients; Utinan and Lonsan bowed back, noticeably deeper than Kodama had. Yamazaki handed Kodama a hefty pile of documents — letters of support from Utinan’s classmates and a copy of an article announcing a writing award that Utinan had won. Then we headed up to the courtroom.

Three judges were waiting. Kodama, Utinan, and Lonsan settled behind a prosecution table. One of the judges motioned to a young female attendant, who collected written statements from the prosecution and the defense and delivered them to the front. For what felt like hours but was really only a few minutes, the judges flipped silently through the thick stack of papers. Utinan stared at his lap; Lonsan bit her lip, her hands clasped atop the table. I scribbled notes, my pen on paper the only sound in the impossible quiet.

Finally, one of the judges opened up a leather-bound calendar to set a trial date. Kodama stood up. He requested that the proceedings be held in November, when school was out and Utinan’s friends could attend. The judge agreed. The class moms sighed with relief. Kodama was encouraged. “Two or three years ago the general trend would be that judges wouldn’t even bother listening to what foreigners had to say,” he told me as we walked out. “Usually the court doesn’t care.”

The group headed to a nearby Italian restaurant to celebrate over spaghetti. I asked Yamazaki why he was so insistent that Utinan seek community support, why having his classmates behind the case was central to their strategy. “This is a human-rights issue,” he said. “Maybe in the States if there were a similar issue you would have institutions supporting his rights. In Japan, it doesn’t work that way. You have to have the community protect Utinan.” They had to show the judges that their own countrymen wanted an outsider to stay — that he really was one of them.

In May, while Kodama was preparing his case, an organization called the Movement for Eliminating Crimes by Foreigners staged a protest in northern Tokyo in opposition to Utinan. On its blog, the group posted, “The fact that foreigners who should be deported straight away for staying in Japan illegally could be legalized is outrageous and horrifying.” A hundred protesters, almost all of them middle-aged men, marched down a wide avenue that had been closed to traffic, chanting, “Get out of Japan!” Many held the national flag above their heads. On the sidewalk were even more people, counterprotesters, who carried signs of their own: no hate, no human being is illegal — a refrain borrowed from pro-immigration rallies in America. They outnumbered the nationalist protesters by hundreds.

I later met one of the counterprotesters, Noma Yasumichi, at a sparsely decorated coffee shop in west Tokyo, where skinny, tattooed waitresses served drinks in mason jars and all the male customers, including Yasumichi, wore oversize beanies. Yasumichi, who is fifty and has a disarming earnestness, is a former editor of Music Magazine. Now he is the leader of the Counter-Racist Action Collective, a group of activists who show up at right-wing demonstrations and create a human barrier between immigrants and fist-pumping nationalists. “The criterion for us is when it’s close to a foreigner’s residence, or maybe a school,” he told me. When he founded C.R.A.C., he spent hours on YouTube watching videos of antiracism protests in Europe and the United States to see how it was done — how activists surrounded the original protesters but never touched them, what they wore, the slogans they yelled. He talked with the Tokyo police and tried to explain his motives, but law enforcement, he said, still sees C.R.A.C as chaos-makers; the nationalists, at least, register their events in advance and don’t block pedestrian pathways. The Tokyo police are known to harangue foreign-looking people on the street or commuter trains, and ask for their papers. Before Utinan surrendered, Yamazaki advised him not to take a bicycle to school, as it was too likely that he’d get stopped for riding on the sidewalk or against traffic.

The irony of Japan’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants, as Yasumichi and others pointed out to me, is that the country has a dire shortage of people. The national birth rate, at 1.4 children per woman, is among the lowest in the world. In 2013, Prime Minister Abe convened a twenty-person panel to discuss ways of encouraging fertility; they came up with a list of recommendations that included assigning gynecologists for life and providing loans to unmarried people for “spouse hunting.” Rural towns have emptied out, and more than 13 percent of the country’s housing stock is vacant. The Japanese economy has fallen into a recession five times since 2008, and by 2050, according to U.N. projections, the population is expected to shrink by more than 15 percent. Soon the country will have more elderly dependents than citizens of working age, slowing growth even further.

Immigration would seem to offer an obvious, immediate solution. “Abe wants to benefit the economy and fill the labor shortage, especially in construction, but he is very conservative about them staying longer term,” Yukiko Omagari, who helped run the Solidarity Network with Migrants, said of foreign laborers. The Solidarity Network is the linchpin of a small but growing collection of NGOs, lawyers, and trade unions that have tried to correct what they see as a masochistic immigration policy. Their goal is to “create a multiethnic and multicultural society in Japan,” Omagari said, but she admitted that it’s a distant possibility. The government’s policies are designed to keep immigrants from staying long, she explained. “They want to get them out after they’ve worked.”

When the Abe Administration has attempted to expand temporary work opportunities for foreigners, the efforts have been troubled. Last year, the government enlarged the Technical Intern Training Program, which offers five-year internships to foreigners at below-market wages. There are now 200,000 such interns, many of them Chinese, who have been placed at farms and factories. There are “terrible violations” of human rights, Shoichi Ibusuki, a Tokyo-based immigration attorney, told me. “I can’t believe a system as bad as it is can continue.” An investigation by Japanese labor inspectors found that 79 percent of the participating companies had denied interns pay, required them to work long hours, and confiscated their passports. A U.N. official declared that the program “may well amount to slavery.”

I visited the office of Heizo Takenaka, an economic adviser to Abe and the chairman of the board at Pasona, one of Japan’s largest employment agencies. In the Pasona lobby, an irrigated rice paddy encircled the reception desk like a moat, and the receptionists, all dressed in short-sleeved navy dresses with pink carnations pinned to their chests, looked like bridesmaids at a Disney-themed wedding. Takenaka told me that he had been working for years on a plan that would increase the number of career opportunities for women, in order to decrease the dependence on immigrants. Sixty percent of Japanese women in the workforce quit after giving birth to their first child; women are paid, on average, 30 percent less than their male colleagues; and they frequently report being bullied at work. Abe has stated that, by 2020, he’d like to see 15 percent of managerial and senior positions at private companies filled by women, and Takenaka believes that if this happens, Japan could avoid easing up on its citizenship laws. Either that, or industries could simply make greater use of robots. “In some European countries, like Germany and some others, immigration provides some serious problems, social problems,” he said. “The Japanese people are very nervous about the kinds of problems caused by immigration.”

In 2015, Takenaka introduced a new short-term visa for foreigners to become domestic workers — considered a dirty, low-status position — which, he hopes, will allow more Japanese women to remain in prestige jobs. The visa, which is being tried out in Kanagawa and Osaka, is modeled after a program that launched in 2008 to attract elder-care aides from the Philippines and Indonesia. Through that arrangement, participants work in a nursing home for three years, at which point they’re given an exam to determine whether they will be invited to stay in the country. But Noriko Tsukada, a business professor at Nihon University’s College of Commerce, told me that managers have recurring complaints of culture-clashing: foreign employees take too long to learn Japanese, Muslim nurses spend too much time praying. A few supervisors told Tsukada that they had banned prayer during the workday and prohibited employees from wearing hijabs. “We are really — including myself — not good at living together,” she said.

Last May, a year after people railed against Utinan in the streets, Japan’s legislature passed the country’s first law against hate speech. Abe supported the bill. “It is totally wrong to slander and defame people of other nations and hold the feeling that we are somehow superior,” he said in 2013, during early discussions. “That would only lead to dishonoring ourselves.” Yet the law is essentially gestural. There’s shame attached to hate speech now, but no real penalties, and only legal residents such as Japanese Brazilians are protected. For someone like Utinan, no accommodations are required, and anything goes.

Utinan’s case was assigned to a new judge, and his trial, twice postponed, was held in June. The sky was overcast, typical for a Tokyo summer. Yamazaki was ill and unable to travel, but about twenty-five supporters accompanied Utinan and Lonsan by bus. Utinan looked dapper in a black suit with a brown tie. He seemed calm as he waited outside the courtroom to be called, his arms hanging loosely at his sides. Lonsan appeared more nervous, her eyes fixed on the floor.

At exactly half past one, Utinan, Lonsan, and their supporters followed Kodama into the courtroom. There were five members of the press in attendance — three with TV cameras, which were turned off when the hearing began. Everyone settled into their seats. Utinan stared at the door, waiting for the judge to enter. The room was as still as a photograph, as if all had ceased breathing.

The judge arrived and faced the group. In my time in Japan, I had found that everything seems to take a lot longer to say in Japanese. During interviews, my translator would often summarize minutes-long soliloquies into a simple “yes” or “no.” But in this instance, the judge delivered the verdict as swiftly as one could imagine. “Kikyaku,” he declared. Mother and son had been rejected.

“Hidoi!” a man in the back of the room, a supporter of Utinan’s, said: “heartless.” He didn’t shout — the civility of Japan was not to be disrupted — but his voice reverberated. Everyone gathered their things and left; the trial had lasted all of fifteen seconds.

Outside, Utinan and Lonsan stood motionless. He was taller than he had been when they’d begun this process, and he had his arm wrapped around her shoulder. He had recently applied for and received a Thai passport — Yamazaki thought it wise for Utinan to have citizenship somewhere — but he had no interest in moving to a country that he’d never known. Two of their supporters broke into tears. A class mom called Yamazaki to leave a message. “We lost — both,” she said, and hung up.

“If we can’t win a case like this, with these two, I don’t see how we can win,” Kodama told me. Nevertheless, he planned to fight the ruling. Utinan kept his eyes downcast, avoiding questions. Later that day, at a press conference, as several more reporters arrived, he was compelled to make a statement. “We are shaken by this decision,” he said. Lonsan stayed out of view of the cameras, crying into her palms.

A few weeks later, Lonsan decided that she would return to Thailand. She had saved enough money, and the judge’s written verdict had suggested that her son’s case would be stronger without her: she did not have any documentation to prove that she was a victim of human trafficking, and she had routinely broken the law for more than a decade by working without a permit. Utinan appealed alone to a higher court, and would remain safe from deportation for as long as it took to process his case.

During the months before Lonsan had to depart, he did little but spend time with her. In September, she flew away, and Utinan moved into a spare room at a friend’s house. He was devastated to be without his mother, he told me, but certain that he had made the right decision. His hope is to become a citizen, finish school, find a well-paying job, and visit her all the time.

In December, Utinan’s appeal was rejected by a high court. Kodama appealed again, to the Supreme Court, but dropped it when other immigration attorneys told him not to bother. Instead, in late January, Utinan made his final petition for permanent residency to the Minister of Justice, through a process outside the court system intended for rejected immigrants whose life circumstances had changed — they married, had a Japanese child — or who would face persecution in their native country. Utinan explained in his application that his mother had left, he was living with a good Japanese family, and his grades were among the top in his class. He’s still waiting to hear back.

“Japan is my home country,” Utinan said at the press conference following the trial in June. “Please let me stay here.” His voice was shaky, but he remained composed. Afterward, one of the reporters would note, with some surprise, how well he spoke Japanese.