In the summer of 2016, when Congress installed a financial control board to address Puerto Rico’s crippling debt, I traveled to San Juan, the capital. The island owed some $120 billion, and Wall Street was demanding action. On the news, President Obama announced his appointments to the Junta de Supervisión y Administración Financiera. “The task ahead for Puerto Rico is not an easy one,” he said. “But I am confident Puerto Rico is up to the challenge of stabilizing the fiscal situation, restoring growth, and building a better future for all Puerto Ricans.” Among locals, however, the control board was widely viewed as a transparent effort to satisfy mainland creditors — just the latest tool of colonialist plundering that went back generations.

All photographs from Puerto Rico by Christopher Gregory

Puerto Rico was given its name (“Rich Port”) for the gold in its rivers. When Spain ceded it to the United States, in 1898, the island was a strategic military outpost; Washington ensured its continued political subjugation and economic exploitation. As residents of a US territory, Puerto Ricans are American citizens, but they are barred from participating in presidential elections and have only a nonvoting representative in Congress. Over time, local activists mounted a fierce resistance, with sovereignty the ultimate aim. Those efforts have quieted in recent years, but when I made my trip, I’d been hearing that there were murmurs of serious mobilization.

Upon my arrival, all I found was a small encampment outside the gates of the federal court building in San Juan, the locus of the American government presence. Anticolonial slogans — fuck usa, doctrina del shock, usa out of pr — had been spray-painted along concrete barricades. A handful of protesters, most of them students, were marching in a circle, chanting and holding signs. But that was pretty much it. Police officers had parked their cruisers down the block and looked relaxed as they observed the goings-on.

Inside the courthouse, I met Douglas Leff, the special agent in charge of the FBI’s operations in Puerto Rico. For years, the local FBI office had served as a bulwark against independence movements, most of them peaceful, though there were some radical offshoots. In 1954, four nationalists stormed the US Capitol in Washington, shooting thirty rounds from semiautomatic weapons and wounding five members of Congress. For the next four decades, agents, in conjunction with Puerto Rican police, mounted an often vicious campaign to quell public unrest.

Lately, however, America’s priorities had evidently shifted from muscling out revolutionaries to collecting on investments: Leff’s background, unlike that of his predecessors, was in white-collar crime. His specialty was complex money laundering and asset forfeiture investigations. A genial and voluble talker with the build of a wrestler, he told me that he had been busy. “Puerto Rico today is like the equivalent of New York City in the Boss Tweed days,” he said. “The financial control board is looking to make sure money is spent responsibly,” he added. “We’re looking at money being stolen.”

Leff had been assigned to San Juan a year earlier, as Washington watched an economic death spiral of its own making. Starting in 1976, Congress had granted a tax exemption on income generated in Puerto Rico by US companies; this, along with low labor costs, made the island a desirable place for corporations, including many from the pharmaceutical industry, to invest. Puerto Rico became increasingly dependent on outside capital. In some cases, a single business employed an entire town; Barceloneta, about thirty-five miles west of San Juan, was at one point responsible for North America’s entire supply of Viagra.

Residents waiting in line for ice, Punta Santiago

But in 1996, Congress began to phase out the tax incentive. In 2006, when the last of its benefits were gone, many of the remaining companies bailed, and Puerto Rico fell into recession. The poverty rate rose to nearly 50 percent, about three times that of the states, and unemployment reached around 10 percent, more than two and a half times as high. The island has about the same number of residents as Connecticut, some 3.5 million, but less than half its GDP: $103 billion to Connecticut’s $263 billion. Over the past decade, as people left in search of jobs on the mainland, the population dropped by 10 percent.

At the same time, Puerto Rico’s government aimed to make up lost revenue by issuing bonds with triple tax exemptions (federal, state, local), in far greater volume than it had before. American financial firms gamely bought in, giving little consideration to the prospect of repayment down the line. From 2006 to 2015, through the sale of municipal bonds, the island’s debt nearly doubled. Default was certain, and the next year, with bond debt rising above $70 billion and about $50 billion in unfunded pension obligations, Puerto Rico declared a state of emergency. Congress passed a bill to create a legal framework for reducing the liability, including the establishment of the control board.

When Ricardo Rosselló, a thirty-eight-year-old graduate of MIT, was sworn in as governor the following January, he found himself mired in the largest municipal debt disaster in history. He released a five-year plan to pay back $800 million annually — which earned him the ire of creditors, who were expecting far more. Territories do not have the right, as local American governments do, to file for bankruptcy, but last May, Rosselló did essentially that, by petitioning a federal court. The control board gave its approval, believing that there was no alternative; both Rosselló and José Carrión, the board’s chairman, released statements meant to head off bankers’ outrage. Yet that would be impossible, as the case was without precedent: the amount of relief that Puerto Rico requested was around seven times what had been sought a few years earlier in Detroit.

The control board understood that its mandate to restructure Puerto Rico’s debt came with a directive to preserve bondholders’ assets. This would inevitably come at the loss of civil programs: among the early austerity measures was a 10 percent cut to pensions, the closure of nearly 200 public schools, a $450 million cut to the University of Puerto Rico’s budget, and the elimination of Christmas bonuses for government workers. A mandatory furlough was put in place for government employees; Rosselló vowed that he would overturn it, yet he had no power to do so. Outcry came from across the island, though Leff, for one, told me that he was not worried about an uprising — people seemed to lack the will.

By August, after spending $31 million (the bulk of it on unspecified “professional services”), the control board had done little to settle creditors’ claims, but had made clear to Puerto Ricans that they would be stripped of the last dregs of their public funds.

Then, on September 20, Hurricane Maria hit the shores.

The Caribbean Sea is prone to storms, and even so the devastation left by Maria was extreme. “It’s the worst hurricane Puerto Rico has seen,” Brock Long, the administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, told the press. In the immediate aftermath, the entire population was without power, and many had no water to drink. A destroyed cellular network left most people without the ability to call for help. As rivers swelled, scores of villagers were trapped by washed-out bridges, and travel across the island was all but impossible. Its lush carpet of vegetation was entirely denuded, and trees were strewn like matchsticks.

A fallen tree on a power line, Orocovis

Naomi Klein, in her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine, describes a phenomenon that she calls disaster capitalism, or the exploitation by private interests of major social and economic crises, such as those brought on by conflict or natural disaster. One of the markers of disaster capitalism — seen, for example, in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina — is the diversion of taxpayer funds to private interests, which depends on a populace too vulnerable to put up resistance. Post-Maria, Puerto Rico looked familiar in this way. Yet here, of course, the disaster long predated the storm. What primed the island for the kinds of austerity measures already in motion were decades of repression so encompassing as to be an assault on society of hurricane proportions.

From the moment it took control, the United States installed corrupt governors who considered Puerto Ricans nothing more than savages; the island was essentially treated as a labor colony whose agricultural resources, particularly sugarcane, were to be tapped for the enrichment of mainlanders. By the Thirties, a nationalist movement had developed, with labor rights as its central platform. The FBI monitored budding independence efforts, but it wasn’t until 1934, when the entire sugar workforce went on strike and shut down production for a month, that federal law enforcement took a keen interest in the “radical” element.

The room in the General Archives building in San Juan where declassified intelligence dossiers, known as carpetas, are stored

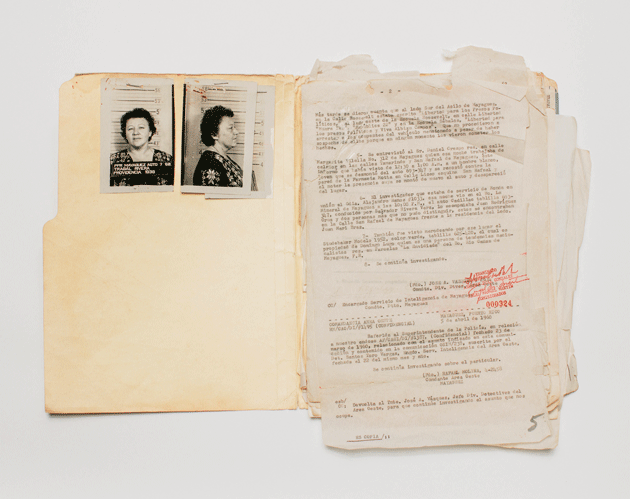

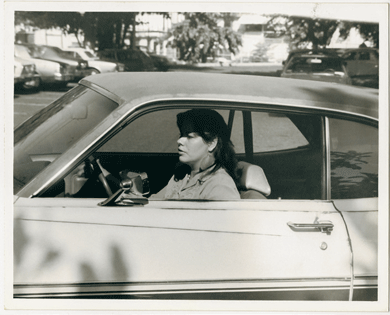

A key artifact of the antirevolutionary operations was the creation, by FBI agents and Puerto Rican police, of nearly two million pages of intelligence dossiers, known as carpetas, that documented the lives of private citizens. At the height of the program, during the Sixties and Seventies, almost everyone was either under surveillance or closely connected to someone on the police’s radar. While I was in San Juan, I visited a bunker-style concrete basement in the General Archives building, where many of the remaining carpetas, which were declassified starting in 1998, are now housed. They are stored in a dimly lit room, packed into rows of metal filing cabinets. Opening random drawers, I found pictures of banal scenes — people shopping, driving, walking down the street — and images of graduations, funerals, and weddings. There were also photos of peaceful university protests on which certain faces had been circled in ballpoint pen and assigned a number, with the corresponding name written on the back.

The carpeta on Providencia Trabal, known as “Pupa,” a leader in the independence movement.

While the FBI kept tabs on civilians, some agents did monitor actual radicals. They focused on the Boricua Popular Army, known as Los Macheteros. In the Seventies and Eighties, Los Macheteros carried out bombings in San Juan, first of an electrical power station and later of a National Guard air base; a few Navy sailors were killed. In all, the group was responsible for dozens of attacks, which they justified as retribution for law enforcement brutality against protesters — most notably the 1978 Cerro Maravilla murders, in which two unarmed activists were ambushed and shot by police. The most brazen act of Los Macheteros, perhaps, took place on mainland soil one morning in 1983: a small group robbed a Wells Fargo depot in West Hartford, Connecticut, taking $7.2 million, at the time the largest heist in US history.

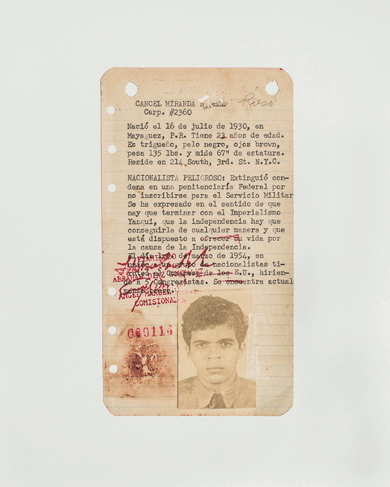

A document from the carpeta on Rafael Cancel Miranda, who served twenty-five years in prison for shooting at lawmakers in the US Capitol in 1954. He was pardoned by President Jimmy Carter.

After I left the archives, I went to see Juan Segarra Palmer, an orchestrator of the Wells Fargo plot. We met over coffee in a gated community near one of the island’s pristine white-sand beaches. Segarra Palmer, who speaks with quiet authority, is sixty-seven; he wears wire-rimmed glasses and has a neatly trimmed beard. His family was wealthy enough to send him to be educated Stateside, at Phillips Academy Andover and Harvard. He returned home in the Seventies. “During those years, there was a lot of union activity, a lot of organizing activity, a lot of environmental issues,” Segarra Palmer said. “I participated in the protests and got beaten up and arrested. I have no problem saying I opposed US colonialism.” He told me it was widely known that surveillance photos taken by law enforcement during those protests were distributed to HR departments at large companies, to prevent demonstrators from finding work. (In the late Nineties, the Puerto Rican government issued an apology for the practice and set up a fund to compensate people who had been rendered unemployable.)

Books listing individuals under surveillance distributed to regional police departments.

Segarra Palmer was sentenced to fifty-five years for his participation in the Wells Fargo robbery. He served nineteen, thanks to a granting of clemency by President Clinton, and was released in 2004. “I got out of prison with a few hundred bucks to my name, and I didn’t want to be a burden to anyone,” he told me. His activism diminished; he found work as a translator. He is like most of his cohort — when I spoke with other activists from his era, I heard similar stories of dwindling resistance.

Cabinets containing carpetas.

The children of that generation received the message. “Repression has taken its toll here,” Segarra Palmer explained. “There’s a general sense that if you oppose the system, you’re not going to get hired and you’re not going to get a job. That’s the legacy of the carpetas. Not so much that you’re necessarily going to go to jail but that you’re going to be blacklisted.”

As a result, a sense of political apathy settled over the population. When I asked Leff about what remains of anticolonial groups today, he said, “We don’t have the same concerns as the large structural organization of the past.” Rather than disrupt revolutionary plots, the sheer volume and force of police presence sapped the populace of the capacity to fight for itself — to make the noise of a democracy.

In the months after my visit, I began to wonder: Even if there were an uprising, would anyone hear it? On the morning of September 25, five days after Hurricane Maria made landfall, Puerto Ricans didn’t seem to have President Trump’s attention. Emergency relief crews dispersed thousands of personnel, including FEMA officers, military service members, and Defense Department teams making medical evacuations; 1.5 million meals and 1.1 million liters of water were delivered. But mayors of remote towns were unable to make contact with officials in San Juan and Washington, so the distribution of aid packages was slow. Most people still had no potable water, gas stations ran out of fuel, and hospitals without power couldn’t treat their patients. Dozens were dying, yet the true number of fatalities would long remain unknown. (An early official count put the number of deaths at sixteen; later, it rose to sixty-four, but the Demographic Registry of Puerto Rico estimated that the toll was actually above a thousand.)

A section of the Old San Juan Cemetery where prominent pro-independence figures are buried. In the center is the grave of Santiago “Chagui” Mari Pesquera, who was kidnapped and murdered in 1976. He was the son of the socialist leader Juan Mari Brás.

In the early afternoon, in a statement he tweeted at House Speaker Paul Ryan, Rosselló wrote, “We will need the full support of the US government. People cannot forget we are US citizens — and proud of it.” There appeared to be a void of capable leadership at the highest level. For days, Trump had said nothing about Puerto Rico. (On Twitter, his comments were largely concerned with condemning NFL players for kneeling in protest of police brutality against black people.)

A surveillance image of an unidentified woman.

Then, as evening fell, Trump broke his silence with a string of tweets: “Texas & Florida are doing great,” he began, referring to the recovery from Hurricanes Harvey and Irma.

But Puerto Rico, which was already suffering from broken infrastructure & massive debt, is in deep trouble. It’s [sic] old electrical grid, which was in terrible shape, was devastated. Much of the Island was destroyed, with billions of dollars owed to Wall Street and the banks, which, sadly, must be dealt with.

On October 12, while feuding with Carmen Yulín Cruz, the mayor of San Juan, who called him the “hater in chief,” the president added, “Electric and all infrastructure was disaster before hurricanes.”

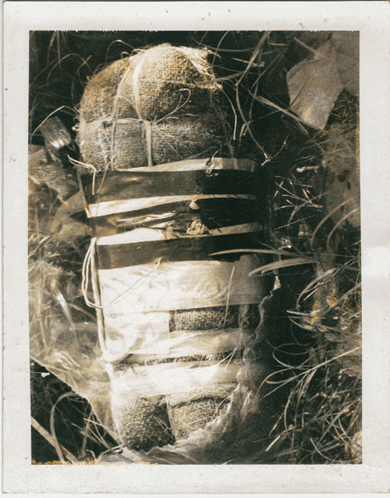

A police photograph of an object presumed to be a bomb.

Trump’s response was callous, but he was right in one respect: Puerto Rico’s infrastructure was in trouble before the storm. It just hadn’t made major headlines.

Since its formation, in 1941, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (Prepa), managed by a board of directors appointed by the governor, has maintained a monopoly on the island’s electricity. Prepa’s development made way for the rapid influx of corporations that sought to take advantage of local tax benefits. But after 2006, when those companies began to leave, utility revenues suffered, too, and like much of the Puerto Rican government, Prepa set about issuing risky bonds. As its financial outlook grew dire, the board borrowed so heavily that Prepa accumulated $9 billion of Puerto Rico’s debt.

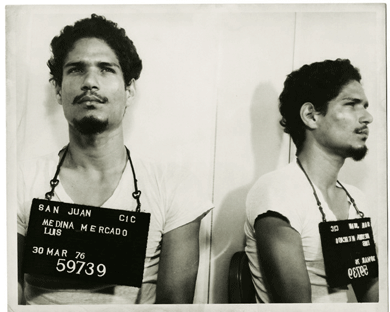

A 1976 mug shot of Luis Medina Mercado, who was arrested for possession of stolen explosive materials along with others allegedly affiliated with the Puerto Rican Socialist Party.

In 2015, by which time Prepa had run out of money for fuel, the Puerto Rico Energy Commission hired Synapse Energy, a consulting firm, to perform an audit. The researchers found that decades of misspending and lack of oversight had contributed to the crushing debt and shortchanged the functionality of the infrastructure — Prepa had been cutting corners on inspections and maintenance to keep the lights on. At particular risk were physical power lines, which Synapse found to be in dangerous disrepair, vulnerable to exactly the kind of natural disaster that would soon occur. The report, published in 2016, concluded, “Prepa’s system today appears to be running on fumes.”

The financial control board, from its inception, made clear its intention to privatize Prepa. In June 2017, four members wrote an editorial for the Wall Street Journal, arguing that “only privatization will enable Prepa to attract the investments it needs to lower costs and provide more reliable power throughout the island.” The next month, Prepa followed Rosselló’s lead by effectively filing for bankruptcy on its own (to pay off what it could to direct creditors), and the control board hired McKinsey to prepare, according to the contract, detailed plans for privatization “supported by financial models and market engagement.”

A utility worker for the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority repairs power lines, Utuado

When the storm landed, ravaging thousands of power lines, among the control board’s first actions was to deputize one of its own, Noel Zamot, a retired Air Force colonel on the executive team, to act as Prepa’s emergency manager. In places such as Detroit, ushering in a private manager with broad powers has meant wresting the last remaining assets from public ownership; with that in mind, Prepa’s governing board immediately rejected Zamot’s appointment, saying that the control board had no right to establish such a role. Rosselló agreed, insisting that because Prepa is a public utility, its management “rests exclusively on democratically elected officials.” In November, Laura Taylor Swain, the US district judge overseeing the island’s overall economic restructuring, handed Rosselló a victory by denying the board’s request to have Zamot formally installed.

Still, Hurricane Maria is sure to ease the way for Prepa’s privatization — either as a single entity or in segments — and enable corruption. Officials in Puerto Rico have said that to make the electrical infrastructure fully operational, the cost could be $5 billion. The US Army Corps of Engineers is doing a third of the work to restore power, with about $2 billion from FEMA, but federal aid is unlikely to make more than a dent in the final bill, and companies friendly with the Trump Administration have already dashed to the scene.

Only six days after the storm, Prepa granted Whitefish Energy Holdings, a young business with two full-time employees, a $300 million contract to rebuild the grid. Whitefish is named for the site of its headquarters — Whitefish, Montana, where Andy Techmanski, the CEO, is neighbors with Ryan Zinke, the secretary of the Interior. The deal quickly attracted suspicion; after several weeks, Prepa revoked the contract and Congress launched an investigation. The House Committee on Energy and Commerce sent a letter to FEMA: “It would appear that the Agency, until now, was not involved in one of the most significant decisions in the effort to rebuild Puerto Rico’s electrical grid.” In a hearing, Brock Long said, “There’s not a lawyer within FEMA that would ever have approved that contract. The bottom line is, it was not our contract. And the other thing, to be clear here, is we don’t approve contracts.” Yet by then, hundreds of hired contractors had already gotten to work, and they would remain through the end of that fall. The bill for each lineman was $319 an hour, nearly seventeen times the average salary for that job in Puerto Rico. (A Whitefish spokesperson claimed that the company had to pay a premium to entice labor.)

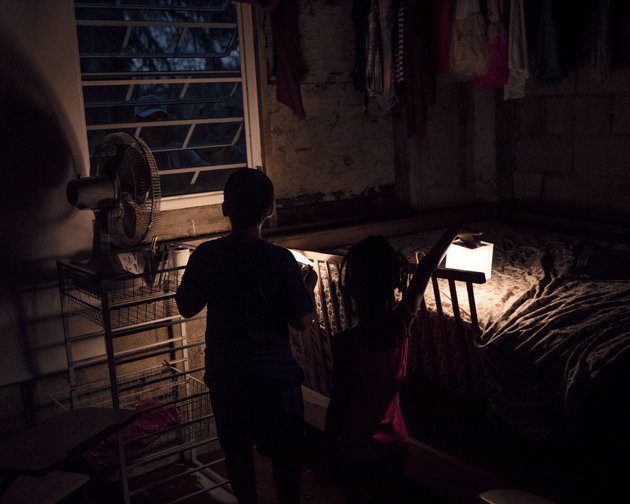

Children whose home was destroyed by Hurricane Maria, Caimito. The solar-powered lanterns they are using were distributed by the mayor of San Juan, Carmen Yulín Cruz.

In October, another contract was signed, for $200 million, to repair poles and power lines; the winner was Cobra Acquisitions. Cobra — a subsidiary of Mammoth Energy Services, an oil-field-drilling and gas-well company based in Oklahoma City — is also fairly new to the utility sector, having been formed in January 2017. This time, Congress had reason to believe that FEMA had given its blessing. In a statement, Cobra said that its managers discussed “the company’s experience, ability to mobilize quickly and its plan to aid in the restoration of power” with Prepa authorities and that they “also met with representatives of FEMA, the Army Corps of Engineers and other key agenices.” The Cobra managers were assured that they would be paid; in a conference call, Arty Straehla, the CEO of Mammoth, said that throughout the negotiations, “in the room, every step of the way, was FEMA.”

Daniel Llargués, a FEMA spokesperson, told me by email that “FEMA was not involved in the selection of Mammoth/Cobra by Prepa” and stressed that “FEMA plays no role in the creation of such contracts.” He added, “We have not obligated any funding for Cobra as of today,” but said that FEMA officials had been “coordinating with Prepa to determine its scope of work and to ensure compliance with established guidelines in order to be eligible for reimbursement.”

The House Energy Committee had doubts about the deal’s terms, which stipulated that Prepa would make a $15 million deposit and that the contract could not be audited. Nevertheless, Cobra has moved forward with plans to hire some five hundred workers for the project.

I asked Leff how these arrangements looked to him. “If the money gets handled properly, then it could trigger investments,” he told me. He would not confirm whether the FBI was actively investigating Prepa, but said that his office had received “numerous allegations” of suspicious practices in recent months. At the FEMA command center, the bureau assembled a team to investigate fraud related to the recovery. “We’re already seeing things,” Leff said. “Corrupt type of networks we wouldn’t have if a disaster hadn’t happened. Sources of money coming in from the feds that don’t go where they should.”

In October, the control board, recognizing that the storm had essentially rendered its earlier austerity plans moot, announced that it would scrap its previous work and present a new strategy this month. Much of what that draft contains will depend on how much federal aid the island ultimately receives. FEMA has committed more than $4 billion, but Rosselló asked the White House for $94 billion. In November, Trump directed Congress to authorize $44 billion for Texas and Florida; he deferred Puerto Rico’s request until “damage assessments” could be completed. Creditors, whose desire to be repaid has not waned in the aftermath of the hurricane, were frustrated by the delay.

Just before Thanksgiving, I headed to the federal district court in Lower Manhattan for a hearing on the status of the bondholders’ dispute. The Puerto Rico case is so complex and sprawling, with so many dozens of claimants, that Judge Swain had assigned some of the work to a colleague, Judith Dein, a US magistrate judge. Dein was handling all matters related to discovery — a key element in determining the true economic status of Puerto Rico, and therefore how much bondholders could demand.

Given the momentousness of the proceedings, I expected a courtroom crammed with journalists, protesters, and onlookers. Yet just as I had been after landing in San Juan, I was disappointed — the public gallery was largely empty. The room was a sea of charcoal-suited lawyers, most of them representing Wall Street. “We are mindful of the suffering on the island, but we all want the same information about the debtor,” Gary Orseck, an attorney for the firm Robbins Russell, said. He was there to debunk the rationale for the control board’s new timeline, arguing that it was “conjuring the image of a flooded basement somewhere, where they’d have to wade through to get the materials.”

In a courtroom high above the city, Judge Dein heard hours of arguments on behalf of the bondholders. At hand was their contention that the board had been less than forthcoming in providing them with critical information on Puerto Rico’s revenues, expenditures, and employment statistics. “When debtors seek to meet their burden, you have to show your work,” Gregory Horowitz, who represents a group of investors holding nearly $3 billion in Puerto Rican bonds, testified. “It’s as if my teenage daughter got marked down on a math exam for not showing her work and said, ‘It’s proprietary.’ ”

As the lawyers made their cases — each with a perfunctory expression of sympathy for the plight of Puerto Ricans — they pleaded that Judge Dein compel the control board to release the island’s financial details while a new plan was devised. “Creditors are being asked to take substantial losses, and we are entitled to know why,” Salvatore Romanello, an attorney representing the National Public Finance Guarantee Corporation, said. “We need to know the status of the debt.”

The control board, for its part, asserted that it had been providing the necessary information all along. But just as important, its updated plan would reflect the entirely transformed conditions in Puerto Rico — nature had taken over their project. As it happened, during the week of the hearing, electricity generation in Puerto Rico had decreased. Some two hundred thousand people were making an exodus to Florida; those who remained faced an existential crisis. “Since the hurricane hit, Puerto Rico is living in a completely new fiscal reality,” Paul Possinger, an attorney for Proskauer, the firm representing the control board, said. “This is a complete game changer. We are starting from essentially a clean slate.”

On the island, the struggle to survive has come to outweigh the pursuit of self-rule. Rosselló, who is a legacy — his father, Pedro, led a statehood crusade that helped launch him into office, in 1993 — is the head of the New Progressive Party, which advocates for state status. But in negotiating for relief funds, he has taken a conciliatory, even diffident tone with Washington. (During a meeting at the White House, he dutifully backed Trump’s claims of a spectacular government response to Maria. “I give ourselves a ten,” Trump said. “You responded immediately, sir,” Rosselló confirmed.)

By contrast, Carmen Yulín Cruz — who took to wearing a nasty T-shirt in defiance of Trump’s dismissiveness — is a political adversary of Rosselló’s, a member of the Popular Democratic Party. Her official platform supports the current territory status, though she is known personally to back local sovereignty. In June, when residents went to the polls for Puerto Rico’s fifth referendum on whether to become the fifty-first state, 97 percent were in favor, but less than a quarter of voters turned out. Cruz was among those who stayed home, for reasons she told to the Guardian: “You don’t fight injustice by asking to become part of the system that committed the injustice against you in the first place. That’s like a freed slave striving to become a slave owner.”

If the United States were to grant sovereignty now, it would be leaving Puerto Rico with a crushing debt load that it has little ability to repay, a broken infrastructure, and a populace weary from the worst storm they have ever known. Still, on November 25, amid the chaos of recovery, some light broke through the clouds: Beatriz Isabel Rosselló, the governor’s wife, gave birth to a boy, Pedro Javier. He came into the world safely, at Ashford Presbyterian Community Hospital, in San Juan. Ashford Presbyterian had backup generators that had kicked in when the power went out, so management and evacuees took to sleeping there in the early days of windblown panic. By the time Beatriz Isabel went into labor, operations were getting back to normal. She stayed a few days, then retired with Pedro Javier to the governor’s residence. “Our son is healthy, and we thank God for that blessing,” Ricardo Rosselló said. Yet no one quite knew what kind of future Puerto Rico’s newborn would inherit.