Discussed in this essay:

The Hatred of Literature, by William Marx. Translated by Nicholas Elliott. Harvard University Press. 240 pages. $29.95.

Literature, William Marx informs us, is a “source of scandal.” It is good that someone thinks so. Literature is more often a source of boredom, pretension, dashed hopes, missed marks, and mediocrity, not to mention softer, homier pleasures such as comfort, escape, and amusement. But Marx, a professor of comparative literature at Université Paris Nanterre, has a taste for the grand and dangereux. Literature is “public enemy no. 1 — the thing we most love to scorn, attack, and belittle”; it is a “punching bag” and a “foil” for philosophers and moralists; it is “what remains when everything else has been removed”; it is “the ultimate illegitimate discourse.” According to The Hatred of Literature, Marx’s new book-length essay (translated by Nicholas Elliott), the scandal is not rooted in any particular novel, poem, or play — it is the audacious, outrageous category itself, literature qua literature.

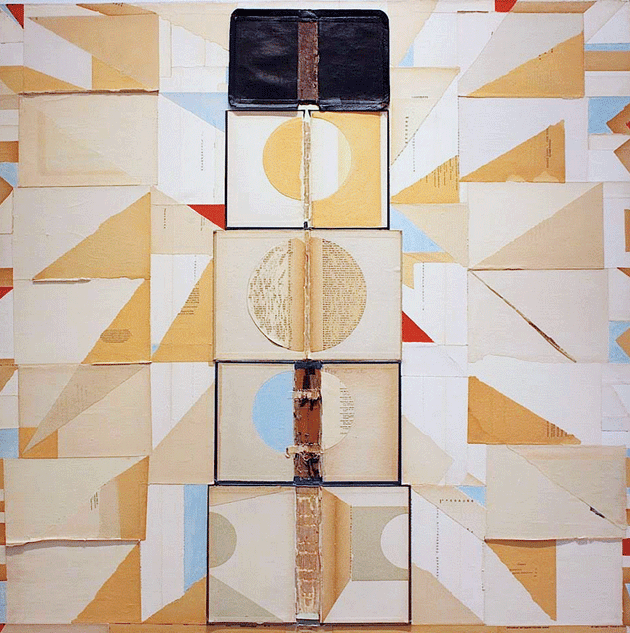

Condensed Books, by John Spinks. Courtesy the artist and Tillou Fine Art, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Marx is an omnivorous, cultivated reader. Skipping from ancient Athens to eighteenth-century France to the contemporary American university, he identifies four “trials” that have turned their prosecutorial energies on literature — those of authority, truth, morality, and society. He is not concerned with actual trials, such as the prosecution of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, or detailed case studies, such as the fatwa against Salman Rushdie; his brief is general, and his interest, to use the academic term, discursive: “What could possibly allow us to group together three thousand years of poetry, fiction, and theater, Homer and Beckett, Aeschylus and Bolaño, Dante and Mishima?” The answer is “antiliterature,” a varicolored, shape-shifting force, the proverbial hammer in search of a nail. Antiliterature is state grants for STEM programs, pedants who jeer at foppish literati, philistines who dismiss poetry as politically inutile, your uncle mocking your English major at Thanksgiving, and anyone or anything that doesn’t bow down to literature as the holiest grail.

A prologue looks back to the hazy past in which the poets channeled the Muses and verse was inseparable from ecstatic rite. “It is when literature begins to have problems that it actually begins,” Marx writes. The first problem is foundational: Plato’s expulsion of the poets from the ideal republic and the elevation of philosophy, the language of reason, to a position of authority — a position held today, with a bit of sore-winner sneering, by science. In the chapter on the trial of truth we meet C. P. Snow, T. H. Huxley, and Gregory Currie, an English philosopher who wrote an article in the Times Literary Supplement some years ago complaining that novelistic psychology is not the same as clinical psychology. Currie then went on to publish an article in the New York Times that asked why there was no evidence, from the lab or from history, to support the idea that literature increases human empathy. Personally I am in favor of any inquiry that pokes at that pious notion, but Marx is having none of it. He spends six pages in a sputtering attack on Currie. Instead of pointing to the unreplicable nature of social science research or Currie’s inattentiveness to literary form, or even arguing over the definition of moral enlightenment, he fixates on the philosopher’s mild observation that some Nazis read books. “There may certainly have been well-read Nazis,” Marx fumes, “but there were far more who were utterly uncultivated, of whom not a word is spoken.” Marx’s central idea, that we can identify the literary less by what it inherently is than by what opposes it, is a true and useful one. But his passion is adolescent, an infatuation that can bear no foul word spoken of the beloved.

The trial of morality, as conducted in the seventeenth century by Tanneguy Le Fèvre against his liberal-humanist father, accused the poets of drunkenness, debauchery, adultery, and “execrable vices that are in our parts rightly punishable by death” — i.e., homosexuality. Morality led to Girolamo Savonarola’s bonfire of the vanities, attempts to ban Huckleberry Finn and The Catcher in the Rye, and “trigger warnings,” which Marx describes as “the result of a reductive and castrating vision of literature.”

“Castrating” is an unfortunate word choice. It is even more unfortunate for following so closely the mention of an incident at Columbia University involving a classroom discussion of the rape of Persephone. I assume that Marx does not mean to say that literature is a great phallus spuming classic tales of rape, which would be admired by all for its beauty and vitality if only overly sensitive female readers would put away their scissors. But I do not know what he means. Worse, he misunderstands what a trigger warning is. (It is the pedagogical practice of alerting a class that some material might be disturbing, graphic, or violent, not a call for censorship.) Nor can I hazard a guess as to why, in his critique of an edition of Huckleberry Finn that replaced the N-word with “slave,” Marx falls back on the falsehood that in Mark Twain’s day the epithet could be “relatively neutral in value.” Such find-and-replace attempts to correct the historical record are harmful as well as moronic, but Marx’s argument would be stronger if it were not itself amnesiac.

The last chapter, the trial of society, dwells on a recent episode from French politics: Nicolas Sarkozy, then a candidate for president, questioned the merit of including a question about Madame de La Fayette’s Princesse de Clèves in the civil service exam. Marx’s point here is that national identity rests on shared cultural objects and traditions, although how we are to determine which objects are included is not something he cares to explain. He ends the book by noting that as literature has been “expelled” from various “territories,” its mandate has been reduced to pure, toothless style. Literature is the “scrap” — what is left over after science, politics, psychology, philosophy, and history have peeled off, taking their claims to morality, truth, and authority with them. That there will always be scrap, and thus always literature, is, he writes, “cold comfort.”

Marx castigates the voices of antiliterature for proposing, in secret, another form of literature, one that is cleaner or simpler, rougher or more essential. It’s a gotcha point — unmasking antiliterature advocates such as St. Paul as clever wordsmiths themselves. But I see something more bittersweet and disillusioned in antiliterature discourse: the fantasy that it might be possible to clear away the brush and see the world for what it is. Antiliterature is less a desire to be free of literature than a desire to be free of language, with all its miscommunications and failures.

“To attack poets is to want to murder the ancient teachers of humanity,” Marx says. There are societies, he admits, in which antiliterary discourse does not flourish. But such societies are those where “literature is considered pure entertainment, a game with no stakes” — I take it this is distinct from “pure, toothless style,” just as aesthetes are distinct from gamers — or in which literature is a handmaiden to authority. Hatred is a sign of interest and passion. As William Hazlitt wrote, “Nature seems (the more we look into it) made up of antipathies: without something to hate, we should lose the very spring of thought and action.” On the one hand, literature has been clipped and diminished to pure ornament; on the other, it still attracts negative attention, so clearly it still matters. Marx concludes that the worst fate that can befall literature is indifference.

Marx talks a great deal about “our” society, and it is not clear whether he means France, where he lives and teaches, or also America and England, or the West in general. Whatever it is, he contends that society is riven by the hatred of literature — and yet in another breath he imagines that we already live in this dystopian world in which literature is an idle pastime. Plato has won. Ours is

a society whose members only ever open a book to experience the purely gratuitous pleasures of the imagination; a world in which literature has lost nearly all power and authority and has become an empty shell merely used to pass the time by a shrinking class increasingly monopolized by many other distractions.

I am not aware of a time after the rise of mass literacy when reading did not compete with other forms of leisure: dance halls, theater, and religious revivals, plus cinema, art galleries, and, more recently, video games. It may feel as though we read less now than we did before the advent of smartphones and social media, but statistics do not bear that out. In January of last year, Gallup found that Americans were consuming books at roughly the same rates as in 2002.

But why is this feeling so prevalent — or, better, who feels this way? Surely the readers and writers engaged in passionate disputes over the politics of representation and cultural appropriation — the very disputes Marx accuses of withdrawing from literature its “right to shock, provoke, and make people uncomfortable” — do not agree that literature is an empty diversion and that the imagination’s pleasures are gratuitous. If literature is a game with no stakes, it is that only for the most powerful and privileged members of our society.

I am thinking in particular of the parcel of real estate at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, where a former reality TV star, an insomniac with the attention span of a fruit fly and a fetish for cable news, paces the West Wing in his bathrobe, tweeting. Last year BuzzFeed published a humor column that imagined Donald Trump’s reviews of classic works, including Ulysses and Wuthering Heights. “Worthless ‘gentleman’ Heathcliff has nasty manners and sees ghosts in his room. Not the sort of person you want as a landlord. Sad!” Of course Trump, who denounces the “failing” liberal media with regularity (“it is the enemy of the American People”), would never waste his breath or tire his thumbs on a novel. His indifference to literature is but one aspect of a larger indifference to reading. Trump asks that reports and intelligence briefings be summarized or delivered orally and loses interest if his own name is not mentioned. His threats to defund the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities were rooted in a callousness that might be monstrous but was not animated by the specificity of real hatred. Just before the inauguration, when asked what he was reading, he gestured across his office. “You can see some of them over there. You can see some of them right over here.” They were not worth naming.

What does it mean to discuss the hatred of literature in the age of Trump? What role could literature — which is, according to Marx’s terms, fictional — possibly play in a national life dominated by a man who is as vacuous as he is brutish? Nowadays it isn’t literature but science that is hated — the torch of authority is bandied about by the consumers of belief-based, self-selecting fake news. In such a moment, one might reasonably propose, defenses of literature ought to take a back seat to the more pressing aim of establishing consensus around issues such as climate change and (the myth of) voter fraud.

Under the Trump presidency, it is easy to become entirely preoccupied with the headlines, which unspool at the breakneck pace of social media. The mood is one of constant emergency, which may be marginally better than the total cynicism that threatens to take its place but is hardly sustainable. If literature has a role to play in this moment, that role will have, I think, something to do with breaking away, with maintaining an inner life. Trump himself has no inner life. He is all externality, all surface, isolated but never alone with himself. His absence of interiority is frightening. How else to read the recent celebration of George W. Bush’s paintings than as a displacement of that fear of Trump’s externality, and of our collective longing for a leader who has if not an intellectual passion then at least a hobby. We know that Bush is no less a war criminal for his interest in color theory, but his paintings remind us that he has the capacity for aesthetic feeling that forms, to some extent, the basis of common life.

In the Trump era, what matters about literature is not its opposition to other discourses or the shiver of scandal attached to it, but the prosaic and everyday activity of reading, which demands withdrawal and inwardness. Unlike watching a movie or visiting an art gallery, reading a book is a solitary pursuit, conducted in the private space of the mind. (Historically, in the West, the interior act of reading has been associated with groups confined, as the scholar Leah Price has written, in “interior spaces: prisoners, children, housewives.”) If reading is not always an act of liberation, it is at least an act of self-definition. It is an experience of solitude in which we become unavailable to those immediately around us. Even when we read to someone else, usually a lover or a child, or have them read to us, the effect is to be pulled together into an orbit defined by the book. In reading we make a public space into something private, and find a way to be private in public.

In The Hatred of Literature, Marx lays down rules for reading. Literature “demands distance, a critical gaze, and hermeneutical perspective.” “Hermeneutical perspective”: the awareness that history informs meaning. Any good teacher would encourage it. “Critical gaze” sounds good, if it means the ability to support an idea with evidence; for Marx, however, it seems to mean an appropriately disembodied reaction to a text. Like “distance,” it’s related to his suspicion of the easily triggered college student who can’t separate her life experience from the material presented in class. There is much to critique in the cult of experience, which makes identity the ground of all knowledge, but the best critique, rather than reinstating the ideals of disinterestedness, would think about what it means to have a point of view. Reading well requires the ability to absorb what is being said, to listen carefully and generously before responding. That temporary bracketing of self, or distance, alternates with intimacy — a close, subjective engagement. Marx is overly suspicious of closeness and not especially interested in the experience of reading. He imagines literature as a prize to be defended or won, rather than an activity you do at home.

In Marx’s demand for distance there is another, unacknowledged desire — for a reading free of readers. It is convenient for him to dump on naïve readers who “wholly, blindly identify” with books. It means he is spared the trouble of thinking about the ways that all “critical gazes,” even his own, are informed by disposition, temperament, life experience, situation — in a word, biography.

We read with our whole selves, and reading helps us discover who we are. We are always in the way, influencing and interpreting as we go. Our consciousness is secret — we have to ask other people, “What are you thinking?” just as we ask them, when the cover is bent back, “What are you reading?” — but it is never really alone. It’s a busy interchange of memory, imagination, experience, and text. What’s more, we are never just reading: we are always reading in a specific place and time, in a certain chair, at the window or in the basement, hot or cold, sleepy or wide awake, alone or in a crowded room. In an essay on Ruskin, Proust writes that when we look back on our favorite childhood days of reading, what we remember is all the interruptions that kept us from the book — the family that was calling us to dinner, for example, the very dinner that was ruined because we spent the whole meal wishing we were still reading. But now the memory of the reading is riddled with all its interruptions, and we look back on them fondly as part of the same event.

Maybe that also describes what it’s like to watch movies or television shows. I don’t think it describes what it’s like to use a phone. But it could be that in ten or twenty years I will look back fondly on these nights on the couch, where I panic over the headlines, compulsively like photos on Instagram, check my email, and return to the headlines on the great hamster wheel of contemporary enervation. Is this reading? Will I recall the interruptions that wrench me away from the latest political disaster with fond nostalgia, the cries of the baby intermingled with tweets about sexual harassment and rising sea levels? What I know is that on the nights when I force myself to open a book, I feel like a person, an individual engaged in an activity at once secret and communal, rather than a receptacle of mass information.

In the essay “Perchance to Dream,” first published in this magazine in 1996, Jonathan Franzen quoted a letter he had received from Don DeLillo. “If serious reading dwindles to near nothingness,” DeLillo wrote, “it will probably mean that the thing we’re talking about when we use the word ‘identity’ has reached an end.” Privacy, personhood, reading, and thinking are all wrapped up together. About this, Marx is right: a future without literature would be a future without scandal; how could there be scandal if everything were already exhibited and known? In such a world we would have followed Trump so closely as to become him — millions of mini-Trumps, issuing our declarations into the void. Sad! It would be flattering ourselves too much to say that reading is an act of resistance, but in these times it may be the only way to stay sane.