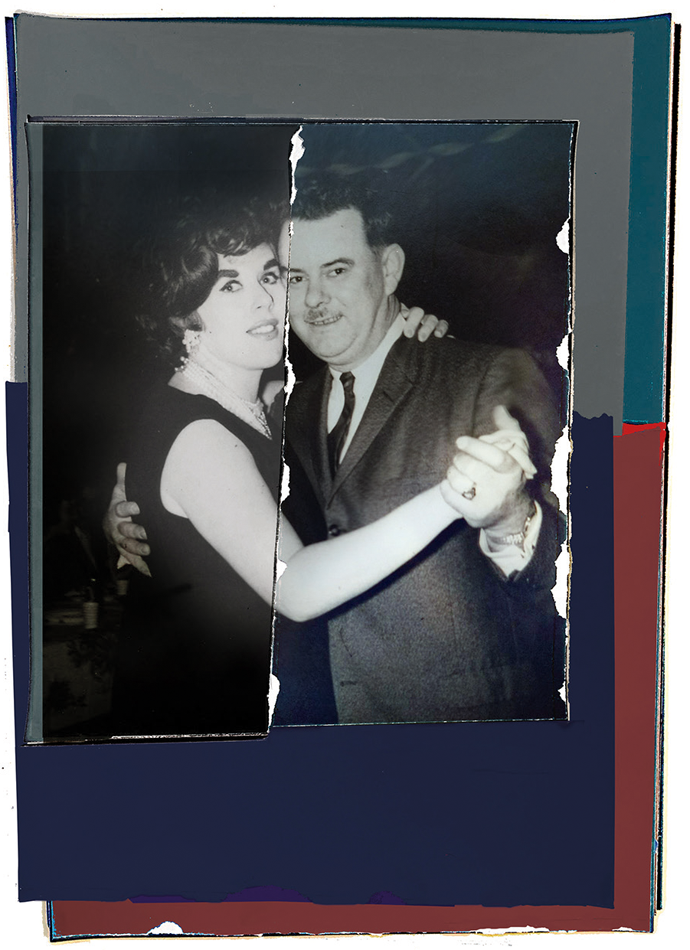

They look so young, and they’re holding each other close. My mother and father, she in a black, sleeveless dress and pearls, he in a single-breasted suit and cuff links. The light of the flashbulb sparkles in their eyes. It’s the happiest I’ve ever seen them, in this image from the black-and-white past; dancing through an old photograph that captured a happier time, a tender moment, inside a sort of intimacy I never would have associated with them.

In all of my recollections of them together, even in those rare moments when they appeared to like each other, there was a wall of separation that never fell. My father, with his deep wounds of experience, and my mother with her uncompromising sense of injustice and rage at fate, remained two souls occupying the same spaces but existing in different realities. It was as if they merely brushed against each other, sometimes passing through each other, but left only ghostly impressions behind.

By the time I was a young teenager, I was not living with them for increasingly long periods of time. I began climbing out of my bedroom window when I was thirteen, taking off into the night in search of what I could not then name. I believe now that I was hunting for love and connection, but I found drugs and violence instead. In the grip of my profound fear of abandonment, I created its realization. I would abandon them before they could abandon me.

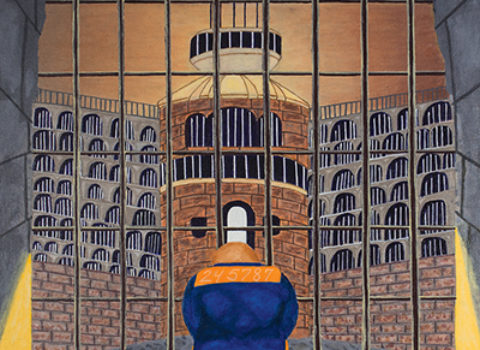

Ultimately, I abandoned all pretense to humanity, becoming a violent predator, exacting revenge on all the world for the sins of my family. All women became my mother and, therefore, objects of fear and loathing; all men, my father, put before me to destroy. I lashed out so severely that I left a wake of broken people behind me, and served more than one term in Lord of the Flies juvenile detention facilities, including the justifiably infamous California Youth Authority. I then killed a man in a drunken fistfight and leapt, headfirst, into the bottomless pit of a life sentence without the possibility of parole, at nineteen years of age.

In the ensuing decades, I’ve unraveled the mystery of how I ran off the rails. The picture that has emerged is one of losses that occurred long before I entered the world, even if the stories are fraught with some uncertainty. My father’s tale is on more solid ground, whereas my mother’s floats in contradictions.

The biggest difference between piecing together the backstory of my mother and that of my father is that he was an honest, if secretive, person. She was prone to exaggeration and outright fabrication. He was basically stable; she seemed tormented. My mother spoke far more about her childhood than my father ever did, and yet I know his story with more clarity and certainty than hers.

Perhaps I was preparing to relate all of this later, because I was forever attempting to pull more out of her. Details came in fits and starts. My mother was born in 1932 to a large family of working-class Irish in Dorchester, a rough section of Boston. She gave birth to my older half-brother when she was seventeen years old. She might have later played basketball for Boston College. She was tall and had a competitive spirit, with a strong throwing arm, but she didn’t graduate. She claimed to have dated Mel Tormé, the famous singer known as The Velvet Fog. I saw pictures of her as a young woman; she was pretty enough, but no proof of a relationship with Mel was ever forthcoming.

In 1942, after a Boston College football game at Fenway Park, 492 people were killed in a fire at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub nearby, still one of the worst fires in history and the sad birthplace of multiple egress rules. Among the victims was a young mother named Patricia Rourke, who had a daughter also named Patricia—my mother, then ten years old. As my mother told the story, she’d had to identify her mother’s body, which always seemed unlikely to me, but it does highlight the long aftereffects of such a traumatic experience. Telling the tale sent my mother back in time all those thirty years, back to the horror of loss, the pain etching lines in her face.

A year before, her father had abandoned her and her younger brother, David. Upon learning of the death of his children’s mother, he appeared and attempted to reclaim young Patsy and Davy. When their father arrived in the neighborhood, around Edson Street, my mother’s uncles went out to meet him in his car, surrounded him, and threatened him enough to run him off. When my mother told this story, it always ended with her father looking directly at her from inside the car before he disappeared from her life, again, this time forever.

My father’s life began in 1925 in Erie, Pennsylvania. He never specifically spoke of his early life, but I’ve been able to piece his story together from clues and hints he dropped during the years we lived under the same roof. Recently, I was also able to review old documents I’d never seen before.

His parents were killed in a car crash in 1931. My father never explained the details of this tragedy, perhaps because he didn’t know them himself, since he was only seven when it happened. The only thing I remember my father ever mentioning about his own father were vague memories of carrying a bucket of beer for him. Where this happened, or under what circumstances, he never told me. If my father had any memories of his mother, he kept them to himself.

His family name, and mine had he not been adopted, was Macumber. It’s believed to be of Scottish origin, the family name of some immigrants who settled in the region in the late eighteenth century. Though my father must then have had blood relatives, he still ended up in an orphanage.

He was eventually adopted by a widowed German woman named Anna Marie Hartman. Because of the depth of feeling his face showed when he spoke of her, and the multiple retellings of arguments he’d had with her, it seems theirs was a complicated relationship, but my father clearly loved Anna Marie and considered her his true mother.

At the age of sixteen, six months before Pearl Harbor, he dropped out of high school and joined the US Navy. He wanted to join an Army unit from Erie with his German-American friends, many of whom formed one of the Ranger battalions that suffered heavy losses on D-Day, but Anna Marie would only consent to the Navy on account of her family’s experiences on the losing side of the trenches during the First World War.

Years after the Second World War, early in the spring of 1960, my father was stationed at South Weymouth Field, a Naval air installation in the Boston area. A chief petty officer, he was probably one of the security detail that boatswain’s mates are usually assigned to when not onboard. Somehow he met my mother, a tall, green-eyed, black-haired single mother of one boy from a failed first marriage. She was an Irish Catholic, he a Lutheran, also a divorcé with two children he would never again see or even mention.

On December 20, 1960, these two damaged and abandoned human beings were married in a civil ceremony in Quincy, Massachusetts. They had already been living together in the small, out-of-the-way town of Scituate. This was, no doubt, because my mother was pregnant—out of wedlock, again—with me. A week and a day later, on December 28, 1960, I was born at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. The fact that it took them almost the full term of the pregnancy to marry is testimony to the reluctance they must have felt—she not ready to marry such a pedestrian, uneducated man; he wary of taking on the task of living with a woman he would always call “Tiger.”

Into this mix of heartbreak and loss I appeared, the physical manifestation of their ill-advised, early spring tryst in New England, in the last months of the Eisenhower Administration: my broken father, a man in his thirties, his failed and hidden marriage, plus two children, receding into the background of his life, sixteen years after surviving a terrifying, storied battle on a small island in the western Pacific Ocean; my headstrong, loud, and volatile mother, an abusive marriage to the right man turned wrong man fresh in her past, fueled by a desperate need to escape the confines of her overbearing family. The two of them embarked on a tortured journey, as one but always apart.

Thus, I am the living product of a forced-by-necessity union of people who could not get too emotionally close to anyone—not to each other, and certainly not to their sensitive and dreamy first son. Although I learned much of the story of their marriage only decades later, I always knew I was the proximate cause. My mother, in her worst moments, would say to me in a chilling, flat tone as undeniable as the thunderclap that follows a lightning flash, “The day you were born was the worst day of my life.”

I felt the tenuous nature of my position with them down into the core of my being. My earliest memory is of coughing into a pillow. I am sitting on the landing at the top of a flight of stairs in our house on Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York. Down at the bottom I can see the blue light of a black-and-white television flickering through a doorway. Suddenly, a younger woman than I imagine my mother could ever have been appears, mid-coughing fit.

“Are you sick?” she asks me.

“I think so,” I reply.

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I was afraid you’d throw me away.”

I was diagnosed with double pneumonia and ended up in intensive care under an oxygen tent before the night was out. My acute fear of abandonment manifested over and over again as my life progressed. This fear is my first memory, and it has never completely left me. It follows me around like the proverbial elephantine presence, occasionally breaking the furniture of my life.

From the outside, we didn’t fit the stereotype of a dysfunctional family. I lived with both of my natural parents. Although we were not well-off, we were not poor. We always had enough to eat, we wore decent clothes and shoes, and our home was both clean and orderly. Every Saturday morning at our lemon-yellow house on Harding Street in Long Beach, California, my younger brother, David, and I were out mowing the lawn, pulling the weeds, and struggling with a manual edger, trying to achieve a line straight enough to satisfy our father’s military standards. On Sundays, he drove all of us to St. Pancratius Catholic Church and waited in the parking lot while we attended mass. Our portrait of normalcy was positively Rockwellian, right down to the rope swing on the tree in the backyard and the family dog barking at the mailman.

Inside, however, behind the always-drawn drapes, the contours of the picture-perfect life warped and came undone. I recall thinking to myself, I’ve never seen them display a single act of physical affection, and I never did. Our version of normal, in private, was abstracted and dark, colored in by the various bruises and lacerations of our parents’ lives. Their suffering was right at the surface. When they abraded each other it often got nasty, though not physical. I often wondered when one of them would kill the other. My mother and father stopped sleeping in the same room when I was very young. There was a constant struggle over who would sleep where to accommodate their separation. My younger sister, Trisha, possibly the fruit of my parents’ last intimate act, got bounced around the most.

My mother manifested the traumas of her life with an ever-changing personality. A shrieking banshee one moment; a laughing, good-natured woman a day or a moment later. She also had a wildly unpredictable and thoroughly irrational, violent streak. In 1969, after the Saturn V moon rocket had blasted into the consciousness of American youth, I got a six-foot-tall model of the Apollo 11 ship for Christmas. I put it together in my bedroom, carefully wetting and applying the black letters on the booster stage and gluing down the escape tower on the top of the command module. Within a few days, over some slight or misdeed or nothing, she had stomped it down to a pile of broken pieces. The next day a new box appeared in my bedroom. I built that model three times. I had several white Panasonic ball-on-a-chain AM radios that tended to fly out of her hand and land on the wall where my head had lately been, among numerous other items that had to be replaced.

But this same woman, with no less intensity, could become tender and loving over the most unexpected event. I remember a rainy afternoon at the close of the school day when I was in the fifth grade at Madison Elementary School in Lakewood. I splashed through the puddles in every depression in the asphalt as I ran to her waiting car. When I got to the door and jumped in, she was lost in misty-eyed reverie.

“Mom, are you all right?”

“You looked so beautiful coming across the schoolyard,” she said as she caressed my damp hair and put her hand against my face. “Your hair was bouncing in the light with every step.” In these moments it was easy to forget all the flying toys and vicious comments. “You know I love you,” she’d say, and even though it often felt more like she was trying to convince herself than reassure me, it helped, a little.

If my mother wore the scars and sadness of her life like a Day-Glo vest, my father disappeared down into his unhappiness. He seemed to always be somewhere else: sleeping in a different room, working on something, meeting someone. He was a mystery man, a specter. A combat veteran of the Second World War, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, he almost never talked about his experiences, and he derided those who did as weaklings or frauds. We shook hands, and I referred to him as “Sir,” because that’s what men did. When he was in Vietnam, my mother assumed a different role, one that required her to be more stable. Looking back at it now, she did better than one would have thought possible, but his presence was sorely missed. When he returned, nevertheless, I rebelled against him with every mindless, reactive breath.

Illustration by Jen Renninger. Source photograph courtesy the author

An early memory: I am very young, and my father looms over me—a stolid tower. Something has happened, and I’m crying. My father intones, in his battle-hardened, Lucky Strike voice, a question with only one, obvious answer.

“Are you a boy or a girl?”

“I’m a boy,” I declare, and suppress what had started to pour out of me. He never had to tell me again how I was expected to act—not like a girl.

Only two tales related to World War II ever leaked out of him. He piloted landing craft at Iwo Jima delivering Marines to a ferociously defended beach. They sat offshore for days while the heavy guns of battleships and cruisers fired broadside around the clock, huge explosive shells whistling overhead, followed by a crumpled thump on the island moments later. The expectation was for a softened resistance pounded down by all those punches delivered.

Unfortunately for the Marines and their Navy comrades, the defenders had withstood the bombardment remarkably well. When the first wave of eager young men poured forth from the landing craft, most were cut down immediately. The first several waves each suffered the same fate and eventually, later arrivals fought from behind a wall of dead brothers in arms. The casualties were astounding. Nearly seven thousand Marines killed and another twenty thousand wounded in thirty-six days of combat. The Battle of Iwo Jima ranks among the most revered and honored of the Marines’ many exploits. Mount Suribachi is hallowed ground for them to this day.

My father would have been twenty years old when he ran the square prow of a landing craft into the soft sands of Iwo Jima, while he watched most of the men within feet of him die and felt Japanese bullets fly by his head, as landing craft went down in the waves around him, their passengers and crew lost in the crimson ocean froth.

He once had a couple of shots of Scotch in him, and a shadow of his youth came out of hiding when he began to tell me this story. His voice lost its usual dull tone. When he got to the point of describing the landing craft disintegrating, he started to disintegrate a little himself. His voice caught in his throat. He paused, made another try, and then stood up and walked straight outside into the night air in the back yard. I could see the orange glow of a cigarette fire up, burn bright, and then, minutes later, fly away in a scatter of sparks. When he came back it was him again, the closed-off him, the damaged him, the orphaned him. I felt then, and to this day decades later, that I glimpsed the essence of my father that night.

Only one other time did he reveal himself to me, if not so clearly or with as much emotive force. We were working on the car. My father was a committed tinkerer, always replacing a part or adding something to improve performance. I think he was never happier or more at ease than when he had on his old khaki pants and a T-shirt, stained with grease smudges, crawling around under the frame of his gray Cadillac Sedan de Ville or leaning down into the depths of its engine compartment. He popped out of one or the other—memory fails—massaging his deformed thumb.

When I was younger, I thought he’d been born with a bulbous thumb—easily half again as big as the other one—but he let on it contained a chunk of shrapnel from the war. When I suggested he have the shrapnel taken out, he said, “No, I don’t want to forget.” I think it may have come from another harrowing episode, one in which he was stationed on a large ship that was torpedoed and sunk at Midway or Guadalcanal. As it sank, he ran down a listing deck, searching out a patch of water that wasn’t aflame with burning oil. He found an open spot, jumped in, and swam to the nearest ship. He climbed the netting over the side and got on deck in time to mount an antiaircraft battery. The gunners were all dead, so he shot down a Japanese plane intent on sinking this ship, too.

My father received some kind of medal for this act of bravery. I learned of the sequence of events from the citation report that I found while searching through his closet one day. It was inside a blue metal tackle box that also contained divorce papers from his first marriage, with the name of his first wife and the names of their two children. They were born in the Fifties, a boy and a girl. That’s all I remember—that and being stunned reading the documents. I wanted to ask him about these siblings of mine, both out of curiosity and the fact that I didn’t much like the ones I knew, but, as moments often go, the right one never presented itself. I still feel cheated that he never mentioned them of his own accord. It would have humanized him a little, this failure to be perfectly honorable.

My father was never easy to understand. He had a tendency to make pronouncements that only made sense years later; at the time, they just seemed out of context and incomprehensible. Once, on the small piece of ground behind our garage that held the clotheslines and served as the dog’s preferred defecation spot, he advised me that I should name a daughter Anna Marie. He didn’t explain why, just that I should.

Years later, he casually informed me that even though he spoke German and was named Hartman—a common name in Germany—we were not German.

“I was adopted,” he told me.

“What was your name before you were adopted?” I asked him.

“Macumber.”

“What kind of name is that?”

“I don’t know.”

“Haven’t you looked into it?”

“I don’t care,” he said, and I’m certain he didn’t. But he cared a lot about a widowed woman named Anna Marie Hartman, and he cared a lot about the orphanages that he supported in the Philippines, and wanted me to care, as well, although he didn’t possess the language to express it directly.

My mother’s family tales were more about how much she hated all of them. She made no distinctions. They were, in her words, “drunks, idiots, and hypocrites.” When I read my parents’ marriage license and saw the date so close to my birth, her fury finally made more sense. The months of accusations of harlotry that her aggressively Catholic grandmother surely threw at her, the second time for my mother, must have left a bruise that never healed. Her first marriage, to a man named McVeigh, who was possibly a doctor—who had probably hit her, based on a couple of cryptic asides—and was certainly the father of my older brother, ended in divorce. Catholics in 1950s Boston, especially the Irish, didn’t get divorced.

I remember asking her, “Why is Peter’s name different from ours?”

“That’s none of your goddamned business,” she answered, and there was never another conversation on the topic.

Like both of my parents, I could not form real relationships with anyone. I lived cut off from human attachments. It became clear to me only later, decades later, that I was suffering from the aftereffects of their abandonments, their tragic losses, their tremendous resentment over creating the indelible bond of a child in the desperation of their loneliness and sorrow. After many years of reflection, in the light of this deeper truth, I’ve made some sense of it all. But I’m only now learning to forgive myself for the acidic acts of brutality that stain my youth, first and foremost, the murder of an innocent man.

In that old black-and-white photograph of my father and mother dancing, I can see the formation, the genesis of my journey. It’s likely my mother is pregnant with me, based on the slightly strained look on her face. And also on the loose black dress and that they are “together” with apparent joy. My father might not yet know. But I’m not certain. He looks more carefree, his tobacco-stained smile broader than I ever remember seeing. It’s striking to me how different they look than they do in my memories of them. But the people they would become are there already, deep in the contours of their faces, hiding in the pain I know lurked within them.

In what must be the oddest twist of their long and painful travels, after their debilitating childhood losses, and that later, unexpected act of creation, they now lie side by side at Arlington National Cemetery. In that hallowed ground, their graves will be tended with care and concern by a grateful nation honoring my father’s years of combat service and my mother’s connection to him. Two orphaned souls adopted by an entire country, abandoned no more.