Discussed in this essay:

Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?, by Graham Allison. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 400 pages. $16.99.

Red Flags: Why Xi’s China Is in Jeopardy, by George Magnus. Yale University Press. 248 pages. $26.

Asia’s Reckoning: China, Japan, and the Fate of U.S. Power in the Pacific Century, by Richard McGregor. Viking. 432 pages. $18.

Rethinking China’s Rise: A Liberal Critique, by Xu Jilin. Translated by David Ownby. Cambridge University Press. 248 pages. $99.99.

Within about fifteen years, China’s economy will surpass America’s and become the largest in the world. As this moment approaches, meanwhile, a consensus has formed in Washington that China poses a significant threat to American interests and well-being. General Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), has said that “China probably poses the greatest threat to our nation by about 2025.” The summary of America’s 2018 National Defense Strategy claims that China and Russia are “revisionist powers” seeking to “shape a world consistent with their authoritarian model—gaining veto authority over other nations’ economic, diplomatic, and security decisions.” Christopher Wray, the FBI director, has said, “One of the things we’re trying to do is view the China threat as not just a whole-of-government threat, but a whole-of-society threat . . . and I think it’s going to take a whole-of-society response by us.” So widespread is this notion that when Donald Trump launched his trade war against China, in January 2018, he received support even from moderate figures such as Democratic senator Chuck Schumer.

Two main currents are driving these concerns. One is economic: that China has undermined the US economy by pursuing unfair trade practices, demanding technology transfers, stealing intellectual property, and imposing non-tariff barriers that impede access to Chinese markets. The other current is political: that China’s successful economic development has not been accompanied by the liberal democratic reform Western governments, and particularly the United States, had expected; and that China has become too aggressive in its dealing with other nations.

Reading about the imminent threat American officials believe China poses, it is not hard to see why Graham Allison, in his book Destined for War, reaches the depressing conclusion that armed conflict between the two countries is more likely than not. Yet since China is not mounting a military force to threaten or invade the United States, not trying to intervene in America’s domestic politics, and not engaged in a deliberate campaign to destroy the American economy, we must consider that, in spite of the increasing clamor about the threat China poses to the United States, it is still possible for America to find a way to deal peaceably with a China that will become the number one economic, and possibly geopolitical, power within a decade—and to do so in a way that advances its own interests, even as it constrains China’s.

Shanghai Broadcasting Building, by Cui Jie © The artist. Courtesy private collection

America must first reconsider a long-held belief about China’s political system. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, American policymakers have been convinced that it would only be a matter of time before the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) followed the Soviet Communist Party into the political grave. Politicians and policymakers on both ends of the political spectrum accepted, implicitly or explicitly, the famous thesis of Francis Fukuyama that there was only one historical road to follow.

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.

When Bill Clinton explained in March 2000 why he supported China’s admission to the World Trade Organization, he stressed that political liberation would inevitably flow from economic liberalization, concluding that “if you believe in a future of greater openness and freedom for the people of China, you ought to be for this agreement.” His successor, George W. Bush, shared the same conviction. In his 2002 National Security Strategy, he wrote, “In time, China will find that social and political freedom is the only source of that national greatness.” Hillary Clinton was more explicit. According to her, by persisting with Communist Party rule, the Chinese “are trying to stop history, which is a fool’s errand. They cannot do it. But they’re going to hold it off as long as possible.”

It is worth considering the conviction of American policymakers that they could so confidently dispense political prescriptions to China. No other empire, of course, has accumulated as much economic, political, and military power as the United States has. Yet, it has still been less than 250 years since the Declaration of Independence was signed, in 1776. China, by contrast, is considerably older, and the Chinese people have learned from several thousand years of history that they suffer most when the central government is weak and divided, as it was for almost a century after the Opium War of 1842, when the country was ravaged by foreign invasions, civil wars, famines, and much else besides. Since 1978, however, China has lifted 800 million people out of poverty and created the largest middle class in the world. As Graham Allison wrote in an op-ed for China Daily, an English-language newspaper owned by the Chinese government, “it could be argued that 40 years of miracle growth have created a greater increase in human well-being for more individuals than occurred in the previous more than 4,000 years of China’s history.” All this has happened while the CCP has been in power. And the Chinese did not fail to notice that the collapse of the Soviet Communist party led to a decline in Russian life expectancy, increase in infant mortality, and plummeting incomes.

In American eyes, the contest between America’s and China’s political systems is one between a democracy, where the people freely choose their government and enjoy freedom of speech and of religion, and an autocracy, where the people have no such freedoms. To neutral observers, however, it could just as easily be seen as a choice between a plutocracy in the United States, where major public policy decisions end up favoring the rich over the masses, and a meritocracy in China, where major public policy decisions made by officials chosen by Party elites on the basis of ability and performance have resulted in such a striking alleviation of poverty. One fact cannot be denied. In the past thirty years, the median income of the American worker has not improved: between 1979 and 2013, median hourly wages rose just 6 percent—less than 0.2 percent per year.

This doesn’t mean that the Chinese political system should remain in its current form forever. Human rights violations—such as the detention of hundreds of thousands of Uighurs—remain a major concern. Within China today, there are many voices calling for reforms. Among them is the prominent liberal scholar Xu Jilin. And in Rethinking China’s Rise: A Liberal Critique, David Ownby has produced an excellent English translation of eight essays Xu has written over the past decade. Xu lodges his sharpest criticisms against his fellow Chinese scholars, and especially against what he sees as their excessive focus on the nation-state and insistence on China’s essential cultural and historical difference from Western political models. He argues that this overemphasis on particularism in fact marks a departure from traditional Chinese culture, which, as exemplified by its historical tianxia model of foreign relations, was a universal and open system. Criticizing the blanket rejection by “extreme nationalists” among his Chinese academic peers of “anything created by Westerners,” Xu argues instead that China has historically succeeded because it was open. However, not even a liberal like Xu would call for China to replicate the American political system. Instead, he argues that China should “employ her own cultural traditions,” through promoting a “new tianxia”: on the domestic front, “Han people and the various national minorities will enjoy mutual equality in legal and status terms, and the cultural uniqueness and pluralism of the different nationalities will be respected and protected,” while its relations with other countries “will be defined by the principles of respect for each other’s sovereign independence, equality in their treatment of each other, and peaceful coexistence.”

China’s political system will have to evolve with its social and economic conditions. And, in many respects, it has evolved significantly, becoming much more open than it once was. When I first went to China, in 1980, for instance, no Chinese were allowed to travel overseas as private tourists. Last year, roughly 134 million traveled overseas. And roughly 134 million Chinese returned home freely. Similarly, millions of the best young Chinese minds have experienced the academic freedom of American universities. Yet, in 2017, eight in ten Chinese students chose to return home. Though the question remains: If things have been going well, why is Xi imposing tighter political discipline on Communist Party members and removing term limits? His predecessor, Hu Jintao, delivered spectacular economic growth. But this period was also marked by a spike in corruption and party factionalism led by Bo Xilai, the Chongqing party secretary who tried to challenge Xi’s rise to power, and Zhou Yongkang, the powerful domestic security chief under Xi’s predecessor. Xi believed these trends would delegitimize the CCP and end China’s successful rejuvenation. Against these dire challenges, he saw no realistic alternative to reimposing strong central leadership. Despite doing this (or, because he did this), Xi remains hugely popular.

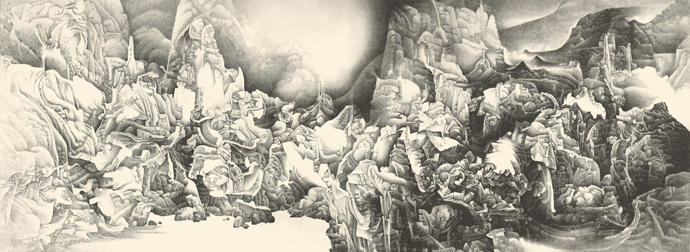

Splendor of Heaven and Earth, ink on paper by Liu Dan, whose work is included in the

exhibition Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World, currently on view at SFMOMA, in San

Francisco © Liu Dan. Courtesy the collection of Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang.

Many in the West have been alarmed by the enormous power Xi has accumulated, taking it as a harbinger of armed conflict. Xi’s accumulation of power, however, has not fundamentally changed China’s long-term geopolitical strategy. The Chinese have, for instance, avoided unnecessary wars. Unlike the United States, which is blessed with two nonthreatening neighbors in Canada and Mexico, China has difficult relations with a number of strong, nationalistic neighbors, including India, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam. Quite remarkably, of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (China, France, Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom), China is the only one among them that has not fired a single military shot across its border in thirty years, since a brief naval battle between China and Vietnam in 1988. By contrast, even during the relatively peaceful Obama Administration, the American military dropped twenty-six thousand bombs on seven countries in a single year. Evidently, the Chinese understand well the art of strategic restraint.

There have, of course, been moments when China seemed close to war. Richard McGregor’s book, Asia’s Reckoning, which focuses on the strategic relationship between the United States, China, and Japan since the postwar period, vividly documents the precarious moments between China and Japan since 2012. After Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda “nationalized” the disputed Senkaku Islands in September 2012, Chinese and Japanese naval vessels came perilously close to each other. Yet while many seasoned observers predicted a military clash between the two countries in 2014, none came to pass.

Much has been made of the possibility of conflict in the South China Sea, through which roughly one fifth of all global shipping passes each year, and where the Chinese have converted isolated reefs and shoals into military installations as part of larger, contested claims to sovereignty over portions of the waters. But contrary to Western analyses, China, while undeniably more politically assertive in the region, has not become more aggressive militarily. The smaller, rival claimants to sovereignty in the South China Sea, including Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, control a number of islands in the waters. China could easily dislodge them. It has not done so.

When considering the familiar narrative of Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, it must be remembered that the United States itself has missed opportunities to defuse tensions there. A former US ambassador to China, J. Stapleton Roy, told me that in a joint press conference with President Obama on September 25, 2015, Xi Jinping not only proposed an approach to the South China Sea that included the endorsement of declarations supported by all ten members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, but, more significantly, added that China had no intention of militarizing the Spratly Islands, where it had engaged in massive reclamation work on the reefs and shoals it occupied. Yet the Obama Administration made no effort to pursue China’s reasonable proposal. Instead, the US Navy stepped up its patrols. In response, China increased the pace of its construction of defensive installations on the islands.

Photograph of a limestone quarry and a temple, Bayin, Gansu, China, by Ian Teh © The artist/Panos Pictures

Just as careful diplomacy is required in military matters, it is also integral to America’s economic relations with China. Virtually no well-known mainstream economist agrees with Trump, or his top trade adviser Peter Navarro and trade representative Robert Lighthizer, that America’s trade deficits are the result of unfair practices by other countries. Martin Feldstein, the former chairman of Ronald Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers, has pointed out that America’s global trade deficit is due to the fact that its consumption outweighs its domestic production. Imposing tariffs on low-cost Chinese goods will not rectify this structural feature, but will serve only to make many essential goods less affordable to ordinary Americans.

Trump’s trade war against China has nevertheless won him broad mainstream support. This is a result of a major mistake that China has made. It has ignored growing perceptions and complaints, including by leading American figures, that China has been fundamentally unfair in many of its economic policies. “The US has a strong case” against China in “alleg[ing] that China persists with discriminatory policies that favour local companies and penalise foreign firms,” as George Magnus notes in Red Flags, recommending that the United States engage China in a dialogue to encourage the latter to open up “market access in non-politically sensitive commercial and service-producing sectors” through avenues such as the US–China Comprehensive Economic Dialogue.

Magnus’s suggestion of dialogue through existing institutions is a far wiser route for America to take than Trump’s trade war. If the Trump Administration were to focus its economic campaign against China on the areas of these unfair practices, it would generate a great deal of global support for this campaign. Indeed, the WTO provides many avenues to do so. Conceivably, China may also privately acknowledge mistakes made in these areas and alter its policies. However, there is a growing perception in China and beyond that the real goal of the Trump Administration is not just to eliminate these unfair trade practices but to undermine or thwart China’s long-term plan to become a technological leader in its own right. Although the United States has the right to implement policies to prevent the theft of its technology, as Martin Feldstein has indicated, this should not be conflated with its efforts to thwart China’s long-term, state-led industrial plan, Made in China 2025, designed to make China a global competitor in advanced manufacturing, focusing on industries like electric cars, advanced robotics, and artificial intelligence.

Both Feldstein and Magnus agree that in order to maintain supremacy in high-tech industries like aerospace and robotics, the US government, rather than pursuing tariffs, should invest in areas such as higher education and research and development. In short, America needs to develop its own long-term economic strategy to match that of China. In both policy and rhetoric, it is clear to see that China’s leadership has a vision for its economy and people. Plans like Made in China 2025 and the infrastructure projects undertaken in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), such as the construction of high-speed railways, demonstrate China’s efforts to become a global competitor in new, advanced industries. At the same time, China’s leaders have emphasized that the country can no longer pursue GDP growth at the expense of social costs such as inequality and environmental pollution. This Xi made clear when he declared in 2017 that the principal contradiction facing Chinese society is now “between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life.” As Magnus sums it up, this means a shift in focus to “improving the environment and pollution, lowering income and regional inequality, and strengthening the social safety net.” Although, as Magnus writes, China’s economy faces several important challenges, China’s leaders have, at the very least, taken steps to address them. It is time for the United States to do the same.

However, to work out a long-term strategy, America needs to resolve a fundamental contradiction in its economic assumptions. Most sophisticated American economists believe that government-led industrial policies do not work, arguing instead for free-market capitalism. If this American belief is correct, Trump’s main trade negotiator, Robert Lighthizer, should not oppose China’s 2025 government-led plan to upgrade its technological capabilities. Lighthizer should sit back and allow this Chinese industrial initiative to fail, as the Soviet Union’s economic plans did.

However, if Lighthizer believes that the 2025 plan could succeed, he should consider the possibility that America should revisit its ideological assumptions and, like China, formulate a long-term comprehensive economic strategy to match the Chinese plan. Even Germany, arguably the world’s leading industrial power, has such a strategy, called Industry 4.0. It’s obviously less intrusive than the Chinese version of industrial policy, which, as Scott Kennedy of the Center for Strategic and International Studies has described, involves the state playing “a significant role . . . in providing an overall framework, utilizing financial and fiscal tools, and supporting the creation of manufacturing innovation centers.” Why can’t the United States formulate a plan to match?

Ironically, the best country that the United States could work with in formulating such a long-term economic strategy might well be China. China is keen to deploy its $3 trillion reserves to invest more in the United States. Adam Posen, the head of the influential Peterson Institute for International Economics, has already noted that Trump’s trade war with China and the rest of the world has led net foreign investment in the United States to fall to nearly zero in 2018. America should also consider participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the Chinese governmental program launched in 2013 to strengthen regional economic cooperation in Asia, Europe, and Africa through massive investments in infrastructure. The countries currently participating in BRI would welcome US participation, as it would help balance China’s influence. In short, there are many economic opportunities America could take advantage of. Just as Boeing and GE, two major American corporations, have benefited from the explosion in the Chinese aviation market, firms like Caterpillar and Bechtel could benefit from the massive construction undertaken in the BRI region. Unfortunately, America’s ideological aversion to state-led economic initiatives will prevent both mutually beneficial long-term economic cooperation with China and needed industrial strategies in the United States.

Dragon’s Birthday, a mixed-media collage by XU ZHEN © The artist. Courtesy James Cohan, New York City

As China rises, America faces two stark choices. First, should it continue with its current mixed bag of policies toward China, with some seeking to enhance bilateral relations and others effectively undermining them? On the economic front, with the exception of Trump’s latest trade war with China, American policies have consistently treated China as a partner, while America’s political and especially military policies have most often treated China as an adversary. Second, can the United States match China and develop an equally effective long-term strategic plan to manage the latter’s rise? The simple answer is yes. However, if China is to be America’s number-one strategic priority, as it should be, the obvious question is whether America can be as strategically disciplined as China and give up its futile wars in the Islamic world and its unnecessary vilification of Russia.

It was rational for the United States to have the world’s largest defense budget when its economy dwarfed every other in the world. Would it be rational for the world’s number-two economy to have the world’s largest defense budget? And if America refuses to give this up, isn’t it a strategic gift to China? China learned one major lesson from the collapse of the Soviet Union. Economic growth must come before military expenditure. Hence, it would actually serve China’s long-term interests for the United States to burn money away on unnecessary military expenses.

If America finally changes its strategic thinking about China, it will also discover that it is possible to develop a strategy that will both constrain China and advance US interests. Bill Clinton provided the wisdom for this strategy in a speech at Yale University in 2003, when he said, in short, that the only way to manage the next superpower is to create multilateral rules and partnerships that would tie it down. For example, though China lays claim to reefs and shoals in the South China Sea, the UN Law of the Sea Convention has prevented it from declaring the entire South China Sea an internal Chinese lake. China has also been obliged to implement WTO judgments that have gone against it. International rules do have bite. Fortunately, under Xi Jinping, China is still in favor of strengthening the global multilateral architecture the United States created, including the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the United Nations, and the WTO. China has contributed more UN peacekeepers than the four other Permanent Members of the UN Security Council combined. Hence, there is a window of opportunity for cooperation between America and China in multilateral forums.

To seize the opportunity, American policymakers have to accept the undeniable reality that the return of China (and India) is unstoppable. Why not? From the year 1 to 1820, China and India had the world’s two largest economies. The past two hundred years of Western domination of global commerce have been an aberration. As PricewaterhouseCoopers has predicted, China and India will resume their number one and two position by 2050 or earlier.

The leaders of both China and India understand that we now live in a small, interdependent global village, threatened by many new challenges, including global warming. Both China and India could have walked away from the Paris Agreement after Trump did so. Both chose not to. Despite their very different political systems, both have decided that they can be responsible global citizens. Perhaps this may be the best route to find out if China will emerge as a threat to the United States and the world. If it agrees to be constrained by multiple global rules and partnerships, China could very well remain a different polity—that is, not a liberal democracy—and still not be a threatening one. This is the alternative scenario that the “China threat” industry in the United States should consider and work toward.