1. As closing time at Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery approached on May 25, 2018, Igor Podporin, a balding thirty-seven-year-old with sunken eyes, circled the Russian history room. The elderly museum attendees shooed him toward the exit, but Podporin paused by a staircase, turned, and rushed back toward the Russian painter Ilya Repin’s 1885 work Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16, 1581. He picked up a large metal pole—part of a barrier meant to keep viewers at a distance—and smashed the painting’s protective glass, landing three more strikes across Ivan’s son’s torso before guards managed to subdue him. Initially, police presented Podporin’s attack as an alcohol-fueled outburst and released a video confession in which he admitted to having knocked back two shots of vodka in the museum cafeteria beforehand. But when Podporin entered court four days later, dressed in the same black Columbia fleece, turquoise T-shirt, and navy-blue cargo pants he had been arrested in, he offered a different explanation for the attack. The painting, Podporin declared, was a “lie.” With that accusation, he thrust himself into a centuries-old debate about the legacy of Russia’s first tsar, a debate that has reignited during Vladimir Putin’s reign. The dispute boils down to one deceptively simple question: Was Ivan really so terrible?

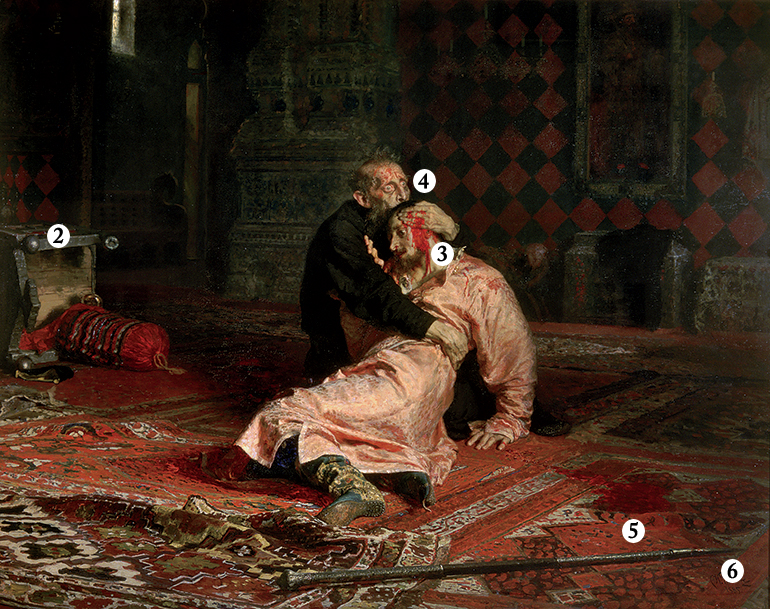

2. Repin’s canvas depicts the sixteenth-century tsar cradling his son, Tsarevitch Ivan, moments after murdering him. Respectable historians don’t tend to dispute the fact of the killing, but they do disagree over the motive. One version holds that father and son had been quarreling over the father’s floundering wars. Another traces the conflict to Ivan the Terrible’s rage against his son’s third wife: when the tsar discovered her dressed immodestly for the royal court, the story goes, he beat her, causing a miscarriage. The tsarevitch then confronted his father, who swung his staff at his son’s head, killing him. The incident accords with the popular characterization of Ivan as a bloodthirsty tyrant. His rule began with a period of reform and expansion, but the tsar became increasingly cruel and despotic as he aged, founding, for instance, the oprichniki, a praetorian guard that roamed on horses adorned with severed dog heads and massacred thousands of boyars, royals, and other subjects deemed to be insufficiently loyal. Ivan’s murder of the tsarevitch contributed to the eventual collapse of the Rurik line and the descent into a chaotic period in Russian history known as the Time of Troubles, symbolized here by the overturned throne.

3. Repin’s atypically gory depiction of the murder roiled Russian society from the start. Some viewers reportedly fainted at the painting’s initial exhibition. Konstantin Pobedonostsev, a powerful insider in the court of the reactionary Alexander III, reported that he “could not look at it without revulsion” and complained that the scene was “entirely fantastical, rather than historical.” Alexander, upset at the portrayal of the first tsar as a murderous madman, forbade the painting to be shown in public. The scene resonated in part because of its charged subtext: Repin’s initial inspiration was the 1881 assassination of Tsar Alexander II and the execution of the conspirators in the face of fierce public opposition. The liberal Repin, who had by then established himself as a prominent member of the peredvizhniki, a movement that married realist aesthetics to a socially conscious outlook, attended the hangings himself. He intended the painting to illustrate the consequences of political violence—in this case, by the autocracy (the father) against the revolutionaries (the son)—but it had the power to provoke a kind of blind rage in its viewers, a particularly dark strain of the Stendhal syndrome. Long before Podporin, a religious fanatic named Abram Balashov had attacked the canvas in 1913, striking it three times with a dagger while crying: “Blood! Why the blood? Down with blood!” The museum’s curator later threw himself under a train.

4. Beyond the blood, the painting’s power derives from its depiction of the murderer’s psyche, particularly from the overwhelming grief captured in the tsar’s wild eyes. As Tatiana Yudenkova, a curator at the Tretyakov, explained, what’s important for Repin is “the contrition of a man who killed.” In that sense, the canvas reflects a second facet of Ivan’s image in the Russian mind: not only a blood-soaked despot but also a tortured figure in search of salvation. In the mid-1930s, Stalin and his officials initiated a reappraisal of the tsar that suppressed both these narratives, recruiting writers and artists such as Sergei Eisenstein to help shape a new account of Ivan that cast him as a great reformer who centralized the empire and warded off foreign enemies, his cruelty warranted in the service of the state. Stalin himself edited Soviet history textbooks to craft a more apologetic view of Ivan’s violent ways. As the historians Kevin M. F. Platt and David Brandenberger have noted, Stalin even struck Repin’s painting from early galleys of The Short Course, the definitive version of Russian history produced during his rule.

5. As modern-day Russia has turned again toward conservatism, nationalism, and repression, Ivan the Terrible has been enjoying another revival of sorts, led by the minister of culture, Vladimir Medinsky. In a series of books, articles, and lectures, Medinsky has suggested that Ivan did not kill his son at all, and that the slanderous tale—Podporin’s “lie”—was spread by nefarious outsiders. A film based on Medinsky’s writings, Myths About Russia: Russian Brutality, aired in 2017 on the country’s most-watched TV channel. As the narrator intones about the evil intentions of Russia’s foreign enemies, fragments of Repin’s painting flash across the screen. One of Medinsky’s books, The Particularities of National Public Relations, a polemic about the supposed manipulations of popular opinion throughout Russian history, features Repin’s painting on the cover. His theories have attracted powerful backers. At a meeting with factory workers in 2017, Putin himself stoked doubts about the tsar’s filicide, suggesting that a papal envoy spread the rumor hoping to convert Russia to Catholicism. Some Russian nationalists now allege that Ivan’s moniker itself is a mistranslation spread by the country’s adversaries, alleging that grozny, rather than “terrible,” ought to be rendered as the comparatively mild “formidable” or “menacing.”

6. By recasting Ivan’s brutality as a prerequisite for progress, the tsar’s proponents have molded him into a prototype for contemporary Russian autocracy. “Only strong leaders are capable of bringing about development,” Vadim Potomsky, the former governor of the Oryol region, told state media in 2016, not long after unveiling an eight-meter-tall statue of Ivan in his city center. Such revisionism requires audacious contortions, such as Potomsky’s claim that Ivan’s son actually died on the road to St. Petersburg, a city founded over a century later. “People have lost the ability to distinguish between works of art and historical facts,” Zelfira Tregulova, the Tretyakov’s director, told media after the attack. During a break in one of Podporin’s hearings—the case is ongoing—his brother conveyed this spirit of historiographical fanaticism. Ivan was a “great leader,” he said. “With all of the great figures in Russia it always happens this way. With Stalin it was the same: he was slandered. And Putin will be slandered, too. It happens with all of Russia’s heroes.” Repin’s canvas, he hinted, exemplified his point. “Just look at that painting,” he said. “It’s asking for it.”