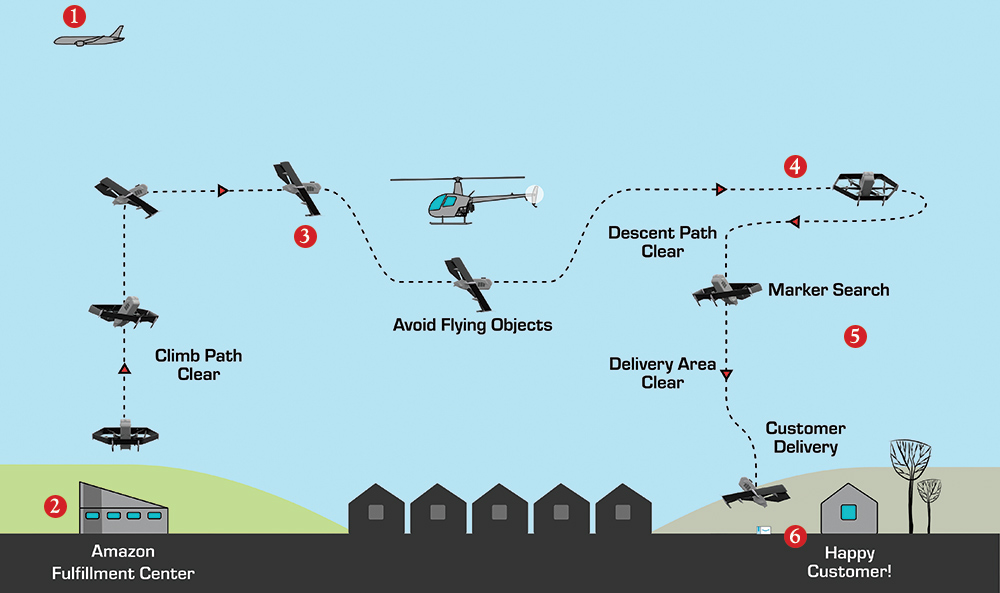

- On December 7, 2016, a drone departed from an Amazon warehouse in the United Kingdom, ascended to an altitude of four hundred feet, and flew to a nearby farm. There it glided down to the front lawn and released from its clutches a small box containing an Amazon streaming device and a bag of popcorn. This was the first successful flight of Prime Air, Amazon’s drone delivery program. If instituted as a regular service, it would slash the costs of “last-mile delivery,” the shortest and most expensive leg of a package’s journey from warehouse to doorstep. Drones don’t get into fender benders, don’t hit rush-hour traffic, and don’t need humans to accompany them, all of which, Amazon says, could enable it to offer thirty-minute delivery for up to 90 percent of domestic shipments while also reducing carbon emissions. After years of testing, Amazon wrote to the Federal Aviation Administration last summer to ask for permission to conduct limited commercial deliveries with its drones, attaching this diagram to show how the system would work. (Amazon insisted that we note that the diagram is not to scale.) Amazon is not the only company working toward such an automated future—UPS, FedEx, Uber, and Google’s parent company, Alphabet, have similar programs—but its plans offer the most detailed vision of what seems to be an impending reality, one in which parcel-toting drones are a constant presence in the sky, doing much more than just delivering popcorn.

- One of the first things Amazon’s growing flock of drones will need is a central hub, the aerial equivalent of a rail yard. Amazon already has dozens of warehouses across the country, but in a number of recent patents, the company has also proposed building “multi-level fulfillment centers” in “densely populated areas.” One of these hypothetical drone hubs resembles an enormous beehive, a conical high-rise with dozens of drone portholes instead of regular windows, like something out of a Pixar film. Trucks would arrive from other warehouses, human and robot workers would shuttle packages through the hive, and “pods or other mechanisms may transport [drones] toward a top of the fulfillment center,” onto a kind of launchpad where “a lift assist mechanism” would apply a burst of “external force” to help the drones take off, like a mother pushing baby birds out of the nest. This shift in the company’s delivery infrastructure could cause a steep reduction in its reliance on Postal Service carriers and independent contractors, though Amazon denies this, citing projected growth in consumer demand.

- Amazon’s latest drone model has six propellers, can fly for up to fifteen miles at a stretch, and can carry packages weighing up to five pounds (which would accommodate up to 90 percent of its shipments), but a company spokesperson said that the tech giant will keep developing different kinds of drones. So far, they have submitted at least four different models for FAA consideration and have filed hundreds of other patents for drone bodies, motors, and sensors. The final model will almost certainly have both a set of propellers to enable vertical takeoff (like a helicopter) and a set of fixed wings to speed lateral flight (like a jet). It’s this design that would allow Prime Air drones to zip over a cityscape at more than fifty miles an hour before lowering themselves just-so between trees and telephone wires.

- The drones’ nervous systems, however—rather than their skeletons—are what should really command our attention. To navigate a city, Prime Air drones will be outfitted with a suite of visual, thermal, and ultrasonic sensors. Together these sensors will create what the company says is a “fail-safe” navigation system, which in theory would help the drones avoid collisions—particularly important given the crashes that have afflicted human delivery contractors. The drones will interact with one another using what company patents call a “mesh communication network” routed through a central database that will negotiate “individual missions” to try to cut down flight times. One patent suggests that if drones need to recharge their batteries, they might be able to dip down to rest on charging stations Amazon could install on “cell towers, church steeples, office buildings, parking decks, [or] telephone poles.” Another suggests that drones could use phone location data to pinpoint drop-offs. The drones will cruise at an altitude of around four hundred feet, where the regulatory pecking order is somewhat cloudy: the Amazon-friendly FAA considers itself the sole regulator of dronedom, but dozens of states and cities have weighed legislation restricting drone use that could prove contradictory.

- At some point, a Prime Air drone will descend from the air and onto somebody’s lawn, where it will need a safe way to deposit its payload. In early deliveries like the one in the United Kingdom, drones have simply lowered themselves down to the grass, but since such a landing could attract thieves, Amazon has also patented a variety of tools to help deliver packages while aboveground, including winched cables and retractable tube slides. Whether they land or not, the drones will get a fairly close look at the space around them. Prime Air customers will likely sign consent forms allowing drones to grace their property, but what if their neighbors don’t want sensor-laden aircraft swooping around their homes? The sensors on Amazon’s current drones are designed to help them avoid hazardous objects, not to record visual detail, but multiple company patents suggest that the drones might one day come equipped with full-fledged cameras and microphones. According to Rebecca Scharf, a law professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, such drone videography would be legal in most of the country, because the devices would only record surfaces already exposed to the public eye, much like the photography used to create Google Maps Street View.

- An Amazon drone, however, could get a more detailed look at customers’ property than a Street View car. And Arthur Holland Michel, the co-director of the Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College, says there would be a market for the information such drones collect. Just as Starbucks uses cellular data to send ads to passersby, Michel says Amazon could use drone footage to suggest future purchases. One patent demonstrates how this might work: a drone, it says, “may capture video data that includes brown and dying trees located near the user’s home.” The company could then recommend arborist services or fertilizers. Amazon’s patents suggest that drones could also analyze “smoke coming from a building . . . structural integrity issues, and/or audio data that indicates gun shots, cries for help, [or] breaking glass.” What happens if a drone captures a crime—would that footage be admissible in court? Scharf says legal precedent protects those who have a “reasonable expectation of privacy,” but expectations can change, and so can ideas about what is reasonable. This data could make Amazon a new kind of merchant, one that collects information not just about what we purchase but about the spaces we inhabit.

Sign in to access Harper’s Magazine

We've recently updated our website to make signing in easier and more secure

Sign in to Harper's

Hi there.

You have

1

free

article

this month.

Connect to your subscription or subscribe for full access

You've reached your free article limit for this

month.

Connect to your subscription or subscribe for full access

Thanks for being a subscriber!

Get Access to Print and Digital for

$23.99 per year.

Subscribe for Full Access

Subscribe for Full Access