Stowaways

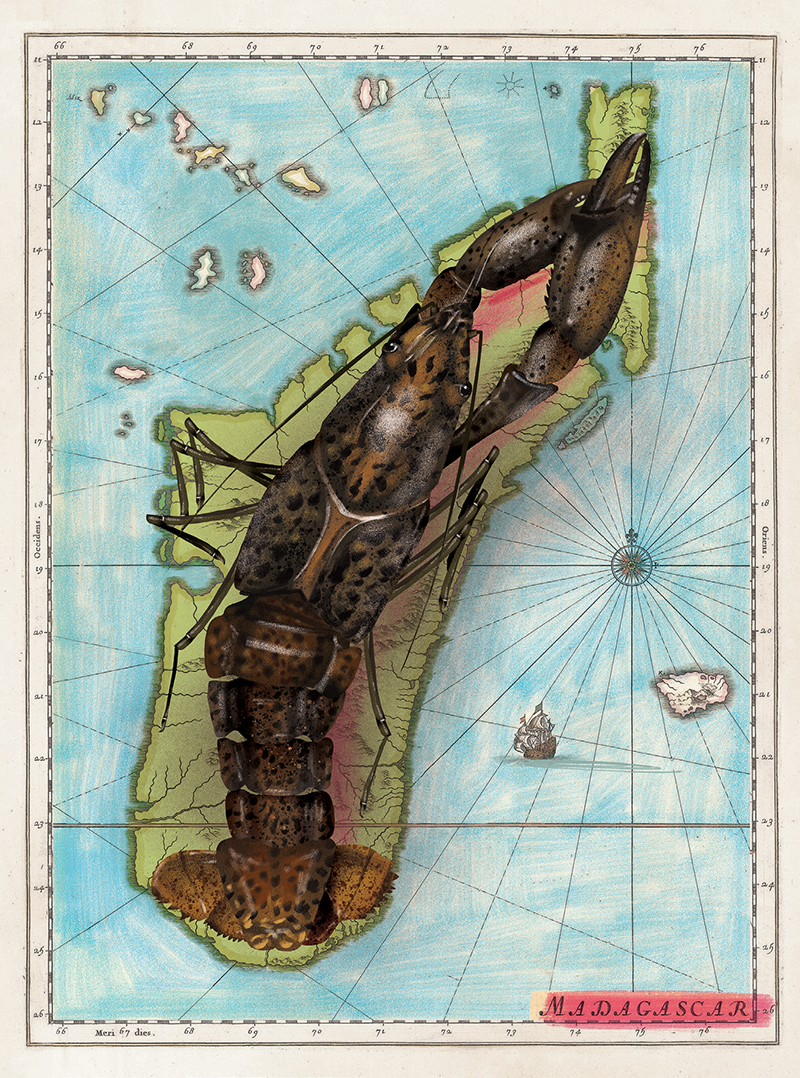

Illustrations by Barry Falls; this illustration based on photographs by Rowan Moore Gerety

Jeanne Rasamy first learned of the marbled crayfish from her milkman. On August 26, 2005, Ra-Eloi came to her door, as he did each morning, with two milk canisters at either end of a wooden pole balanced across his shoulders. This time he also carried a straw basket he used to sell fish that he caught in the flooded rice paddies near his home. Inside was a small, grayish crustacean with a marbled pattern on its shell. He was hoping that Rasamy, who had been a biology professor at the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar’s capital for more than forty years, might be able to tell him what it was.

Rasamy thought it looked like a crayfish, but it was much smaller than the native species she’d studied, and its eggs were black instead of orange. Curious, she asked the milkman to show her where he had found it. A few weeks later, Rasamy walked down the hill from her house to the edge of the vast floodplain on the eastern fringes of the city. It was a short distance as the crow flies, but she’d have to finish the trip by canoe. Ra-Eloi lived in one of Antananarivo’s so-called bas-quartiers, or low neighborhoods—flood-prone areas surrounded by wetlands. In a rice field near his house, he and Rasamy set up a woven fish trap and quickly collected a handful of the strange creatures, which ranged from the size of a paperclip to that of a finger. Rasamy took photos and brought a few back to her lab to measure and examine under a microscope. But these scraps of data weren’t much use without some idea of what the mystery creatures were, or where they had come from.

Rasamy decided to inquire at the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries. A receptionist directed her to the freshwater fisheries program, where she produced one of the specimens from her bag, sloshing around in a shallow glass beaker. The official was friendly but clueless. Rasamy turned next to Julia Jones, a biologist at Bangor University, in Wales, whom she’d met while Jones was researching Madagascar’s endemic crayfish for her dissertation. Jones didn’t recognize the crustaceans either. “Maybe they’re prawns?” she said.

A year passed before Jones got an email, out of the blue, from a German shrimp and crayfish breeder who had ordered crayfish online; the dealer had sent the wrong species, and they’d come wrapped in Malagasy newsprint. Alarmed, he wrote to Jones: Do you realize that Marmorkrebs is wild in Madagascar?

When Rasamy began researching the marbled crayfish, it was still virtually unknown to science. The earliest murmurs about the emergence of a new, self-cloning crayfish bubbled up among German aquarists in the mid-Nineties. Collectors who owned only female crayfish inexplicably ended up with dozens more in a matter of months. There were, apparently, no males whatsoever.

Marbled crayfish reproduce through a process called parthenogenesis, in which females lay large clutches of fertile, genetically identical eggs, cloning themselves by the hundreds every few months. Some species of bees, fruit flies, and aphids also reproduce this way, as do even some larger animals. Female sharks, snakes, and Komodo dragons in captivity have made the news when handlers discovered that they were pregnant despite the absence of males. Among vertebrates, roughly one in a thousand species can reproduce through parthenogenesis, including a few dozen kinds of lizard—almost always as a result of mating between two species, leading to all-female hybrid offspring. But marbled crayfish stood out: among the more than fifteen thousand known species of decapods—the huge and ancient family that also includes crabs, shrimp, and lobsters—none were capable of cloning themselves. And no one could remember seeing this crayfish before the mid-Nineties.

Initial research suggested that Marmorkrebs, German for “marbled crayfish,” belonged to a family of American crayfish called Cambaridae, which are considered potent invasives on three continents. The first mainstream academic paper on the marbled crayfish, a one-page brief published in Nature in 2002, warned that “the release of even one specimen into the wild would be enough to found a population that might outcompete native crayfish.” Rasamy and Jones were worried about what the crayfish could do in Madagascar, where freshwater ecosystems are especially precarious; nearly half of the island’s freshwater species are threatened with extinction. In 2008, Rasamy and Jones published a paper on marbled crayfish in Madagascar, which they titled “The Perfect Invader.”

In a world connected by shipping routes and air travel, few places are more susceptible to the law of unintended consequences than Madagascar. For nearly one hundred million years, after its landmass split from Africa and the Indian subcontinent, the island drifted in an evolutionary vacuum, surrounded by an ocean that discouraged all but the rarest incursions from outside visitors. Plants and animals evolved, without interference, into ever-more-specialized niches, until 80 percent of the flora and fauna there existed nowhere else. The same hyper-specialization that produced Madagascar’s unusual biodiversity also makes its wildlife particularly vulnerable to habitat loss, climate change, and competition from invasive species. Scholars disagree about the date of Madagascar’s earliest human settlements—estimates range from 2,400 to more than 10,000 years ago—but it’s clear their arrival hastened the extinction of many of the country’s largest creatures, including pygmy hippos and lemurs the size of grown men. Today, discoveries of “new” species are relatively commonplace—an average of more than one a week over the past two decades—but many are classified as threatened as soon as they’re discovered.

The field of conservation abounds with cautionary tales of invasives: Burmese pythons rampaging through the Everglades, cane toads in Australia poisoning everything in sight. In Madagascar, biologists often cite the fibata, or blotched snakehead, a shimmering species of carnivorous fish first imported in the Seventies by the dictator Didier Ratsiraka. He became interested in the fish after a state visit to North Korea, where snakeheads are widely cultivated, and then arranged to import a shipment from China in hopes of jump-starting a domestic fish-farming industry. The shipment of snakeheads was split between the ponds of the presidential summer residence, north of the capital, and Ratsiraka’s hometown of Vatomandry, in the east. Within a few years, flooding breached the banks of the presidential ponds, and the fish—capable of traveling over land during droughts—made its way into natural waterways. Today, the fibata are a scourge of rivers across western Madagascar, devouring native fish and insects wherever they go.

Since its discovery, the marbled crayfish has expanded its range in Madagascar by more than a hundredfold. Its population now numbers well into the millions, from the highlands of Antananarivo down to the Indian Ocean, and in countless ponds, rice paddies, and streams in between. Biologists have observed this process with a mix of curiosity and trepidation. One early fear was that the marbled crayfish could spread a fungus known as the crayfish plague to its larger, slower-growing cousins in the genus Astacoides, which are native to the mountain streams of Madagascar’s southeastern rainforests. Another concern was that the hyper-fertile invasives would eat or outcompete native species in freshwater ecosystems already driven to the brink. But even as scientists feared the worst, many of Madagascar’s poorest citizens came to embrace the crayfish as a cheap and abundant source of protein. In a few short years, farmers and traders took stock of the unfamiliar creature and developed a new segment of the economy, building up a supply chain that now stretches halfway across the country. At a market near Rasamy’s house, you can buy crayfish live, peeled, or parboiled, sorted and priced by size.

Like the fibata before it, the marbled crayfish presents a dilemma that dovetails with an urgent debate over the role of conservation in the Anthropocene. Human settlement has remade landscapes everywhere: bamboo and eucalyptus where they don’t belong, the proliferation of species like starlings and pigeons. If it’s too late to turn back the clock, what kind of future should conservationists aim for? Should they fight to rehabilitate the planet we’ve despoiled or adapt to the one we’ve created? The answer can only be both at once. And yet the marbled crayfish shows how difficult it can be to strike that balance.

Antananarivo can be a maddening place to navigate. Some say the name, which means “city of a thousand,” refers to its one thousand hills. On foot or by car, it’s all hairpin turns and long stairways; rice paddies are tucked between the slopes. Water travels easily through a lowland maze of marshes and ponds linked by canals. In 2006, a tropical cyclone dumped heavy rains on the city, and the crayfish population boomed. Antananarivo had no crayfish-eating tradition to speak of, yet the trade blossomed in markets across the city.

As one of the scientists who had first tried to identify the crayfish, Rasamy felt as though she ought to do something to contain its spread. In 2007, she secured a small grant from Conservation International and set off with a team to survey areas around the capital. Their primary goal was to determine how widely the marbled crayfish was distributed; but they also started a publicity campaign, warning farmers of the animal’s potential to disrupt rice cultivation and wreak havoc on native fish. The team made posters and stickers that read marmorkrebs: danger!

Back at the University of Antananarivo, the biology department hosted a group of environmental officials for the first formal meeting concerning the foza orana, or “crabby crayfish,” as it came to be known across the country. Rasamy delivered a PowerPoint presentation containing field photographs and information she’d gleaned online about the life cycle and ecology of similar species, and the officials seemed to take note. Soon afterward, the agriculture ministry issued a regulation forbidding all transportation of marbled crayfish beyond the suburbs of the capital. Briefly, police officers even made spot checks for crayfish at city bus depots. Rasamy did radio interviews and traveled from town to town, attending dozens of meetings with local officials, farmers, and environmentalists. In Moramanga, along the road that descends from the capital into the humid forests of eastern Madagascar, the mayor listened to her presentation and then immediately banned the sale of marbled crayfish. “He was the only one,” Rasamy said wistfully.

Overall, these efforts had little effect. Rasamy’s message was drowned out by the mystery of the marbled crayfish’s biology and the appeal of its price point in a country where 75 percent of the population lives on less than two dollars a day. Foza orana was soon the cheapest protein on the market—cheaper than eggs or even dried beans. As a saying in Antananarivo had it, the marbled crayfish is “a small animal from who-knows-where that can sustain the family.”

The marbled crayfish capital of Madagascar is a remote riverside town called Mahasoa, which boasts as many oxen as people. It’s a day’s walk from the paved road, or an hour and a half by jeep, through vistas of rolling, golden grasslands and bald granite peaks; the milky-brown expanse of the Ihosy River lies off to the south. When I visited, in 2019, piles of rice were drying on tarps alongside the road. I pulled to a stop outside a ramshackle house where an old woman with a gray ponytail sat against the wall selling crayfish fritters.

My guide and translator on the trip was a twenty-five-year-old graduate student from Rasamy’s university. Our first obligation, as in any rural community in Madagascar, was to see the chef fokontany, or head of the local government. We found Jean Ramandrosoa, who has held his post since 1997, in a small dark office opposite the market, with president painted in white lettering above the doorway. Ramandrosoa is in his fifties and rail thin, with hollow cheeks and a solemn bearing. He nodded along to my introductory spiel, then stood up and grabbed a megaphone off the wall. Outside his office, a crowd formed as he began to speak.

“This vazaha is here to learn about tsi pe’peo,” Ramandrosoa said, using the local name for the crayfish, which comes from the way they move their claws. Anxious laughter rippled through the crowd. He recapped my brief account of the crayfish—its relation to an American species, its popularity among German aquarists, its sudden arrival in Antananarivo—and then began freestyling. “Perhaps he is here because the government sent him,” the chef fokontany said. A man sitting against a wall across the street raised his hand and asked why I was really there: Was I trying to sell them tsi pe’peo?

As the chef fokontany finished his speech, a middle-aged woman in a fishing hat appeared at the edge of the crowd. She was carrying a large wooden hoop fitted with mosquito netting, and a small bucket hung from a scarf tied around her waist—a rig for crayfish harvesting. Marie Claudine Jeanne de Chantal Rasoanantenanana, who introduced herself as Madame Claudine, said she was one of the few full-time crayfish harvesters in Mahasoa. As the crowd dispersed, she led me to the yard of a nearby house to sit on empty five-gallon water jugs and talk shop. For most people, Madame Claudine explained, collecting crayfish is part-time, seasonal work. It starts in December, in the austral summer, when rains swell the banks of the Ihosy River and flood the terraced rice paddies that line the hills. After months of sheltering from the dry heat underground, marbled crayfish emerge from their burrows by the thousands, making it possible to collect five or six pails in a few hours.

This population boom is well-timed, occurring in the middle of what Malagasy farmers call the hungry season—before the rice harvest, when the previous year’s stock has been eaten or sold and the new crop is still weeks or months away. Crayfish offer an opportunity to make a bit of extra income or fill the family stockpot during lean times. But Madame Claudine said she had moved to Mahasoa specifically to collect crayfish full-time. Neither she nor her husband had inherited enough land to make a living as farmers. They left home as young adults, and ended up in a sapphire-mining town doing menial work for foreign gemstone traders. Madame Claudine cleaned houses and washed clothes. Her husband hauled water from a communal spigot to other people’s kitchens. After almost twenty years there, tired and just as poor as they’d been when they arrived, they heard about tsi pe’peo and decided to move to Mahasoa.

Even in the winter, Madame Claudine spends afternoons and evenings dragging her net through the muddy shallows of the river until she has enough crayfish to sell to one of the dealers who make regular runs to Ihosy, a nearby market town on the paved road, in the middle of the night. It’s relatively light work, and Madame Claudine sets her own schedule, but it’s still a precarious way to make a living—anywhere from 75 cents to a few dollars a day. “It depends on the water,” she said.

That afternoon, I walked down to the riverbank to meet Jean Christophe Razafindralambo, a farmer and fisherman who had offered to show me crayfish up close. Razafindralambo, who goes by Jean Chri, is a compact, muscular man with a few days’ stubble and a choppy haircut. His dual occupation means tending to his rice paddies in the morning and taking to the river with his traps and nets in the afternoon, sometimes sleeping on the islands in the river to prevent anyone from stealing his catch.

It was a beautiful, cool day. Children skipped along the water’s edge, eyes glued to their crayfish hoops, while adults planted rice in the muddy flats. Jean Chri arrived with a friend in a boxy dugout canoe half-filled with rice hulls, standing at the bow wearing a bright-orange T-shirt printed with the face and campaign slogan of Madagascar’s president, Andry Rajoelina. After I hopped aboard, Jean Chri guided us out into a series of shallow inlets where the current was weaker. Periodically, he grabbed a double handful of rice hulls and gently lowered them into the water, marking each spot with a bit of tall grass stuck in the mud. He’d return after an hour or so and throw a lead-weighted net over each marker, capturing any crayfish that had gathered to feed on the bait. At the height of crayfish season, this method can bring in enormous quantities—enough to fill a rice sack in a single afternoon. “Tsi pe’peo aren’t afraid of humans,” he told me. “You don’t need to be fussy about disturbing the water.” Some days he could make as much as 35,000 ariary, or about ten dollars, a rare take in Mahasoa. But a banner fishing day could bring in more than twice as much, and it had been a while since he’d had a day like that. “Tsi pe’peo are destroying the fishing,” Jean Chri said. This echoed what I’d heard from scientists: marbled crayfish have been known to devour the larvae of valuable species such as tilapia and black bass.

In Mahasoa, nearly everyone participates in the crayfish economy in one way or another. People use them to fatten up pigs and chickens, or eat them with rice. Yet not everyone is enthusiastic about the new interloper—fishermen worry that crayfish are hurting their haul, and farmers complain that they’re damaging rice cultivation. No one had asked for a new and unfamiliar commodity crop. It just showed up.

In the hills above town, where rice cultivation depends on rainfall for irrigation, farmers complain that the levees of their terraced paddies spring leaks without warning, sparking arguments when valuable rainwater drains into their neighbors’ fields instead. Most realize that crayfish burrows are to blame, but suspicions linger all the same. “The tsi pe’peo is an enemy of agriculture,” Ramandrosoa told me. Nevertheless, he hesitated to advocate for its eradication. For families without even enough money to pay their children’s school fees, he said, “It’s kerosene, it’s sugar, it’s soap. It’s the basic necessities.” In the lean months, Ramandrosoa explained, “People collect crayfish so they don’t have to sell their rice.”

Traveling up and down Route Nationale 7, the main axis of the crayfish trade, I found that the mere mention of the marbled crayfish was enough to send people into peals of laughter. At a market in Fianarantsoa, shrimp vendors chuckled when we asked for directions, amused at the thought of a foreigner seeking out an obviously inferior product. “Why do you want foza orana?”they said. “We’ve got shrimp.” In Ihosy, the Catholic nun who ran the guesthouse where I was staying told me that the diocese fed its pigs crayfish shells to fatten them up before slaughter. She turned up her nose at the idea of people eating crayfish, too. “They’re not edible!” she said. “Foza orana are in dirty water, eating dirty things. They introduce microbes into your body.”

As they’ve spread, the marbled crayfish have developed an unsavory reputation linked to the sewage-tainted canals and grinding poverty of the lowland neighborhoods where they were first discovered. In Malagasy slang, foza orana has become a kind of insult, shorthand for anything abundant, cheap, and low quality. Ten-dollar Chinese flip phones and knockoff sneakers are foza orana. When President Rajoelina first came to power, in a coup d’état in 2009, opponents began slandering him and his supporters as foza orana, a label variously tied to his penchant for flashing the V for victory at rallies; the bright-orange color his political party shares with cooked crayfish; and the notion that Rajoelina was, like a crustacean dragging its prey, moving the country backward. Around the same time, the singer Ramora Favori released a hit single called “Foza Orana” that denigrated young women for their perceived promiscuity.

Each stop on my journey brought out different theories about where the marbled crayfish had come from. A woman at a market in Ihosy said she’d seen three Chinese men take a cooler out of the trunk of their car and dump the contents into the river—soon thereafter, she started seeing crayfish everywhere. My taxi driver in Antananarivo was sure the crayfish were part of a Chinese government conspiracy, an attempt to establish control over a new seafood-export business. Some said that white people had dropped the crayfish out of planes. When I told one farmer that the earliest marbled crayfish sightings had been in Germany, she nodded, and at the end of our conversation, an hour later, asked, “Germany—now, is that outside of Madagascar?”

The marbled crayfish is one of those invasive species that prompt daydreams about the experiments found in science fiction, as though its creator were messing around in the lab after reading too much Isaac Asimov. In reality, its origin story is ordinary enough to seem even more unlikely.

The first evidence of the marbled crayfish’s remarkable life cycle reached the scientific community in 2000, when a former student at Heidelberg University approached his old professor, a crayfish expert named Günter Vogt, to ask whether Vogt might be interested in studying a specimen he was raising in an aquarium at home. The crayfish appeared to be reproducing furiously without any males in the tank. Vogt used a few of those offspring to seed a laboratory population at the university and devoted a semester-long course to deciphering their anatomy. In 2004, he published a paper that confirmed the crayfish’s capacity to clone itself.

Still, for years, biologists argued about where the crayfish belonged on the tree of life and what it should be called. The research pointed to a pair of kindred species from Florida, but scientists disagreed about whether the marbled crayfish was closer to the blue crayfish (P. alleni) or the slough crayfish (P. fallax). Was it a hybrid, a subspecies, or something else entirely?

On close observation, they looked almost identical to female slough crayfish, except that they grew larger and laid more numerous clutches of eggs. Male P. fallax placed in a tank with the marbled crayfish went through all the usual courtship rituals, and even mated, but this was misleading: DNA analysis of the marbled crayfish’s subsequent offspring revealed no traces from P. fallax. The offspring were genetically identical to their mothers. Both the sameness of the marbled crayfish’s DNA and its genetic distance from its closest relative pointed to one explanation: somewhere, somehow, a single mutation event had given rise to a new, independent species. In 2015, after some wrangling over the name, scientists decided to call it Procambarus virginalis.

By this point, Vogt was working with another former student, Frank Lyko, on an ambitious effort to sequence the crayfish’s genome, a project that was being run out of Lyko’s lab at the German Cancer Research Center. If successful, they would be able to trace the marbled crayfish populations scattered across the world—in Ukraine, Japan, and Madagascar—back to their genetic source, giving the species an official birth date.

As far as Vogt could tell, all the early Marmorkrebs collectors could trace their specimens back to an aquarist who had begun passing them around Heidelberg in the mid-Nineties—the same former student who had approached him in 2000. Sequencing their genomes confirmed as much. After five years of work, Lyko and his team had a clearer picture of the species’s genesis: two slough crayfish from somewhere near Gainesville, Florida, had mated, and one of them had a mutation in its reproductive cells that produced extra chromosomes. The resulting embryo—the very first marbled crayfish—had three copies of each chromosome. Buried somewhere in its cache of supplemental DNA was an ability for eggs to divide into embryos by themselves.

Working backward almost twenty years later, Lyko had the mystery collector’s name—what he called, with regret, a “fairly common German name”—but no contact information. The former student, whose aquarium had birthed a globally invasive species, didn’t seem anxious to attract attention. Whenever he had time, Lyko poked around the internet looking for phone numbers and email addresses associated with the name. Finally, in 2017, he got a response from the umpteenth Frank Steuerwald he’d written to, now a district manager for Germany’s national mosquito-control agency, working in the forests of the Rhine Valley.

Curious to see how the descendants of his original crayfish were developing, Steuerwald visited Lyko’s lab and told the story of how he’d acquired the first specimens, at an insect fair in Frankfurt in 1995. Among those on the regional exotic-pet circuit at the time, Steuerwald said, was a pair of middle-aged vendors with a good selection of tarantulas and a reputation for dealing in anything they could get their hands on, legal or otherwise. Steuerwald bought from them regularly, but he says he never saw either of the men use the same name or phone number twice. One day, he purchased a half dozen of what they misleadingly called “Texas crayfish” and brought them home in a plastic bag.

No one knows for sure how the marbled crayfish’s progenitors made it from the United States to Europe, but Vogt has a theory: Steuerwald’s suppliers brought the crayfish over on an airplane, perhaps in checked baggage stowed beneath the cabin, where it would have been near freezing. With farmed shrimp, Vogt explained, it’s well known that temperature shocks can cause a mutation linked to parthenogenesis, though the ensuing clones are thought to be sterile. But in this case, the stress of the transatlantic journey could have caused a mutation in one of the embryos. By the time the shipment arrived in Frankfurt, it may have held the parent of a brand-new species.

So far, the marbled crayfish’s expansion has largely steered clear of Madagascar’s singular wildlife. Crayfish density remains highest in market towns near Route Nationale 7, in a vast plateau that consists almost entirely of eucalyptus, pine, and cattle-grazing grasslands. That pattern may not hold. In 2019, one of Rasamy’s students found marbled crayfish in the same waters as the blue-tinged Astacoides betsileoensis and another native species, Astacoides granulimanus—evidence that they are steadily moving east toward the rainforests of Ranomafana National Park. Exactly what that might mean for the freshwater ecosystems in the region is unclear, but it’s not looking good. As Jones put it, “We have absolutely no idea.” What scientists do know is how quickly they can multiply. The marbled crayfish is omnivorous and voracious. If, as the crayfish colonize more intact ecosystems, they feed on native species instead of invasives such as black bass, then the nightmare Jones and Rasamy worried about a decade ago could yet materialize.

In the meantime, there’s no national strategy to manage the ecological impact of the marbled crayfish or to capitalize on its commercial potential. It has earned mention alongside other invasive species in a handful of book-length policy documents, but that’s about it. As Hiarinirina Randrianijahana, a veteran technician at the Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development, told me, “The problem for Madagascar is that there’s not yet a specific law that governs invasive species.” If someone wants to introduce a novel species—as Russian sturgeon were introduced a few years ago to jump-start the domestic caviar industry—there’s a process laid out in the ministry’s regulations. “But if it’s accidental . . . ” He trailed off.

The more time I spent knocking on doors in search of an official response to the marbled crayfish, the more I wondered whether the stigma that has developed around the creature has led to a paralysis by ambivalence. The coordinator of Madagascar’s national community nutrition program told me in an email that he would be interested in a pilot program to test the potential of the marbled crayfish as a commodity crop, but he devoted many more words to misinformation about the crustacean’s negative health effects and status as a disease vector. (Though all aquatic species can absorb pollutants from the water they inhabit, there’s no evidence that eating crayfish presents any increased health risk.) This echoed the reaction of a doctor I met at a Catholic clinic in Ihosy, who told me that he counseled his patients against eating crayfish because of their dirtiness, and then, with no apparent irony, added that two thirds of the children he sees suffer from malnutrition. More than once, officials I spoke to treated crayfish consumption as a punch line. Etienne Bemanaja, the country’s director of fisheries, told me, “If we want to eradicate it, we’ll need to eat it!”—letting loose a belly laugh at the thought.

But after a decade of half-hearted attempts have failed to slow the spread of the marbled crayfish, some scientists think it’s time for the government to update its approach. Together with Ranja Andriantsoa, a former student of Rasamy’s who now works with Lyko on crayfish genomics, Jones has started researching the social and economic dynamics resulting from the crayfish’s spread. Again and again, Andriantsoa said, people complain about the crayfish’s effect on rice production, only to turn around and name it as a staple in the kitchen. “It’s very popular now commercially, but we still have this note from the ministry that we’re not allowed to spread or transport live marbled crayfish,” she said. “The species is there, and it’s established. What can we do with it?”

In Louisiana, peeled crayfish has been a Cajun delicacy for generations. Double-cropping, in which farmers alternate between growing rice and allowing crayfish to proliferate as they feast on decaying straw, is practiced on a third of the rice-growing acreage in the state. China has overtaken Louisiana in terms of production, but worldwide it has become a multibillion-dollar industry. With cheap labor and a dependable supply of the most prolific crayfish on earth, Madagascar is well positioned to take over a share of the market. But doing so would require investment from more than just the farmers and fishermen who have turned to the creature out of necessity.

Rasamy shuddered when I raised the possibility that research and government investment might bolster the market for marbled crayfish. “We don’t dare,” she said. “There’s too much risk.” Fifteen years into this vast, unplanned experiment, Madagascar remains caught in a kind of purgatory, unable to contain the marbled crayfish but unwilling to seize on whatever silver lining its invasion might hold.

Last spring, after Madagascar’s president declared a lockdown to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, I got an email from Rasamy lamenting the conundrum we’ve all become familiar with during the pandemic—the way public-health directives and short-term economic interests seem impossibly at odds. In Madagascar, where a huge swath of the labor force spends each day earning the money they will use to buy supper, the tension is particularly pronounced. “People can’t stay home, because they have to go out every day to look for a way to put food on the table,” she wrote.

The lockdown shuttered schools and public transit, and the army was responsible for enforcing social distancing in the capital. But as in the case of the marbled crayfish, the government has not been in a position to understand the full extent of the virus’s spread. Though Madagascar’s coronavirus numbers may seem comparatively low—17,000 cases and 250 deaths since last March—the entire country has administered fewer COVID-19 tests in that time than the state of California now processes in a single day.

The country’s lack of resources offers only a partial explanation for such anemic testing; President Rajoelina has devoted considerable national resources to Covid-Organics, an unproven herbal coronavirus remedy that is made from artemisia plants. The World Health Organization has cautioned that the product has not been rigorously tested, but Rajoelina has aggressively marketed it abroad.

If the cure were effective, Covid-Organics would represent a dramatic and unusual convergence of political will and problem-solving rooted in Madagascar’s natural resources—just the kind of initiative that could help make an industry out of the country’s most bountiful unnatural resource, marbled crayfish. As it stands, Madagascar is in the midst of a rainy season that is certain to accelerate the spread of the crayfish, and has not developed a plan to slow the process down. Andriantsoa, the former student of Rasamy’s who now works at the German Cancer Research Center, is back in the field, tracking the expansion of marbled crayfish populations using environmental DNA analysis, which detects traces of waterborne genetic information left by molted crayfish shells.

This data could prove invaluable for Andriantsoa’s colleagues, who became interested in the marbled crayfish as a model for the growth of cancerous tumors. Like the crayfish, tumor cells are fast-growing, self-cloning, and susceptible to genetic changes in response to environmental conditions. What these researchers learn about how the crayfish adapts to changes in temperature, nutrients, or pollutant levels could shed light on the factors that lead cancers to become more aggressive. But it won’t do much for Madagascar unless Andriantsoa manages to break the spell—part stigma, part resignation—that has helped the crayfish get this far.

When I returned to Antananarivo after my tour of the countryside, Rasamy agreed to take me to see her milkman’s village on the outskirts of the city. Her husband dropped her off at a busy intersection on the road to the coast; she got out of the car wearing a patterned blouse, a floppy hat, and a photographer’s vest. She hadn’t been back since her first visit, more than a decade earlier. After stopping to ask for directions, she led me across a massive construction site to a narrow berm jutting out between rice paddies being filled in for a new highway. A row of tiny brick houses stretched along either side, perched above a murky, trash-strewn canal where ducks swam in the shade of peach trees and haggard banana plants. This was Ampasika, the first place in Madagascar where the marbled crayfish is known to have been seen.

The milkman was at church, but Rasamy chatted with his neighbors for the better part of an hour about the declining fish harvest, the low prices they got for their goods at market, and the struggle to protect their rice fields from the crayfish’s endless burrowing. Many of them spent their days scouring the landfill for plastic water bottles, which they sold to a Chinese recycling outfit for a little less than a penny apiece. Rasamy looked depressed. “You just don’t imagine the conditions people live in,” she said.

People in Ampasika had their own theories about the provenance of the first, fateful crayfish that arrived in Madagascar—something to do with a Japanese construction project called the Boulevard de Tokyo. But Rasamy had lost enthusiasm for my endless conjecture about the crayfish’s origins. “For me, it doesn’t matter,” she said. Instead, she was trying to reconcile herself to the reality of its future in Madagascar.

In this, she had much in common with the people I’d met in Ihosy and Mahasoa, and in the lowlands around Antananarivo, for whom the invasive species is both a bane and a blessing. The marbled crayfish’s blend of utility and nuisance, its stigma and its affordability, boil down to a situation in which even people who make a living off the animal say without hesitation that they would like to see it wiped off the map.

A local agriculture director told me the dynamic reminded him of a parable from southern Madagascar, in which a village leader tries to stave off widespread crop damage from locusts by ordering every man, woman, and child to go out and collect the insects while they are still buried in the soil in the larval stage; in the process, the village builds up a vast store of larvae to cook and eat in lean times. “Hunting locusts,” he said, “is at once an obligation and a way to find food.”