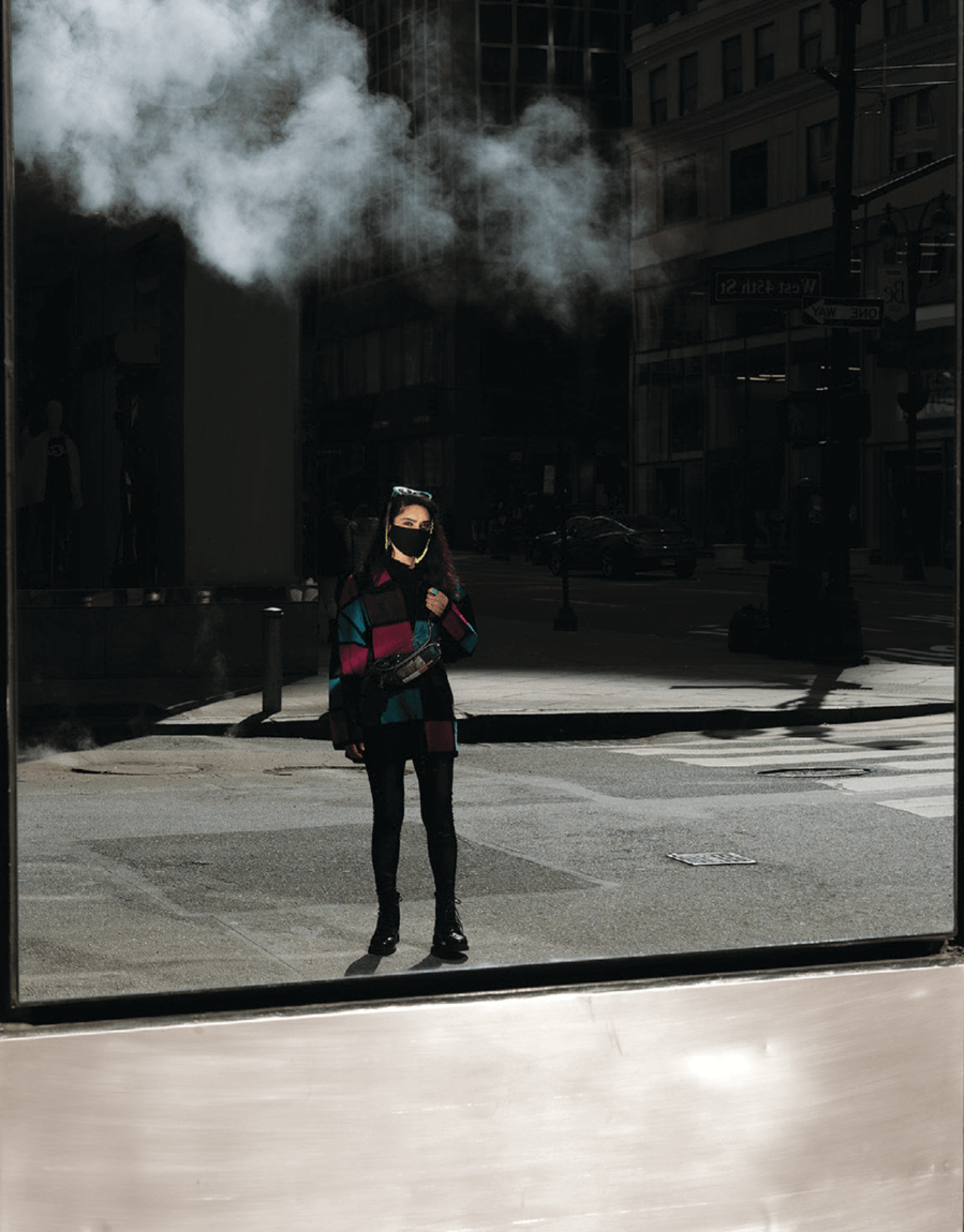

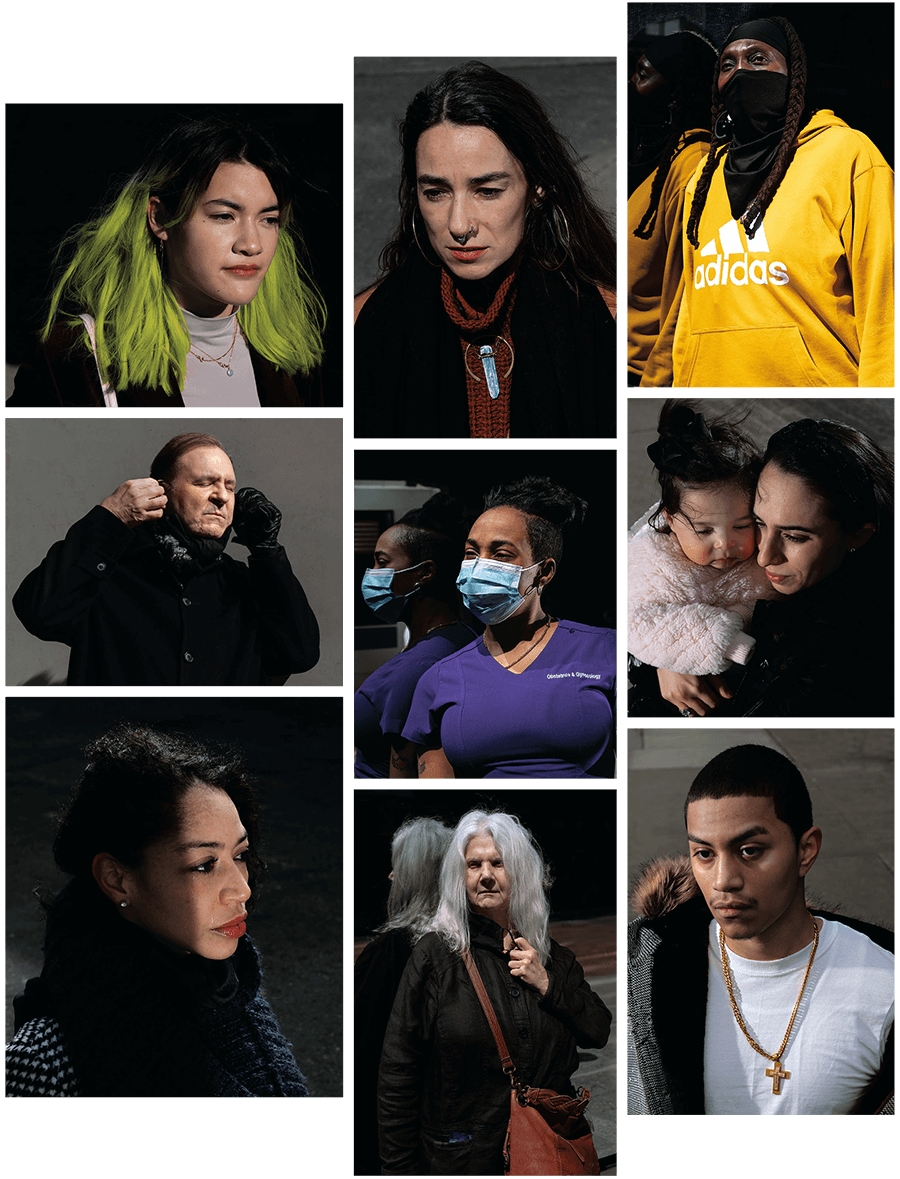

One year after the COVID-19 pandemic reached New York City, Elizabeth Bick took a series of portraits of strangers on the streets of Manhattan and from the window of her studio in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn. All photographs by Elizabeth Bick, March 2021, for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

There’s a particular stranger I remember from deep in my past. I was six years old, in a playroom at some kind of day camp. I saw a pretty brunette girl standing with a group of her friends. She struck me as older and more sophisticated than I was, though she couldn’t have been more than seven or eight. She met my gaze and asked, “Do you have a staring problem?” I was shocked, ashamed—and understood that I should not look at people for long. But I still stare at strangers; I still have a staring problem.

I used to see strangers every day when I commuted to an office on a train. Often I couldn’t get a seat, and though I always carried a book, I rarely opened it. The trips were short, the cars were full, and I was never bored. I spent the time looking at the other passengers—their outfits, what they were reading; the interesting neutrality of their train expressions, unrevealing of their interiors.

Ten years ago, when I moved to Denver and started working from home, I didn’t miss seeing my co-workers, exactly, at least not as specific people. But I found I missed seeing people in general. I missed the strangers on the train. So I’d wander around a mall after work, or go to concerts or museums. (Friday night openings are barely about the art; they’re about looking good in public.) In his 1712 essay “Twenty-four Hours in London,” Richard Steele writes,

I could not believe any Place more entertaining than Covent-Garden; where I strolled from one Fruit-Shop to another, with Crowds of agreeable young Women around me, who were purchasing Fruit for their respective Families.

The eighteenth-century convention of capitalizing nouns transforms these “Women” with their “Fruit” into Platonic ideals; it’s as if he was delighted by their very interchangeability.

To people-watch, says Baudelaire, is “to see the world, to be at the center of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world”—to become interchangeable, one of the strangers. For Virginia Woolf, a wander through the city at dusk was an escape from the trap of being “tethered to a single mind,” from the oppression of self: “The evening hour, too, gives us the irresponsibility which darkness and lamplight bestow. We are no longer quite ourselves.” “Let us dally a little longer,” she writes, “be content still with surfaces only.” Strangers are all surface, and if we accessed their depths, they’d cease to be strangers. We’re all surface to them, too—all face. Strangers allow us to be mysterious in a way we can’t when we’re at home, or when alone. With strangers we’re unknown.

For over a year now, I have not been seeing enough faces. My dreams have become crowded, creating company for me. I go to dream parties and talk to old friends—sometimes very old friends, people I haven’t been in touch with for decades—and make out with dream strangers. (I heard once that the strangers in your dreams are all real people you’ve seen in the past, in fleeting encounters, but how could you ever prove this?) A writer I know told me she’s been searching for faces online so that she can work on her novel: “I’ve never had to do this before! But it’s like I can’t see my characters anymore. I can’t remember the tiny details people have on their faces.” The same day, another friend shared a photo with me, writing, “Last night I saw a woman feeding this cat and I stopped to tell her how I saw it sunning itself in this chair. Best interaction all week!” Another: “One of the things my students mentioned missing the most from pre-COVID days was just seeing strangers and smiling at them in passing.”

I used to read a blog by the psychologist Seth Roberts, where he documented the results of elaborate experiments in optimizing his life and daily habits: to maintain a lower weight, to achieve better sleep and better moods. One of the odder things he discovered was what he called morning faces therapy: “If I see faces in the morning, I feel better the next day.” It’s as though we have a basic need to see other people, a recommended daily intake of humanity. Roberts believed he could satisfy this need by watching talking heads on TV or YouTube, but I’m not so sure. I think we need faces that can see us, too.

One day last July I saw a letter to the editor in the Baltimore Sun that made me gasp. “My 8-year-old was sobbing last night because she misses playing with her friends at recess, she misses her teacher, and she is worried that everyone has forgotten her,” a mother wrote. “At one point she asked me if she was even real anymore.” I felt profound recognition in this child’s crisis—the self cannot be too much with itself, it seems. We need to be seen or else we feel transparent, even nonexistent.

For much of the summer, I had a near-constant headache, and some other sensation I couldn’t describe. I tried to tell people what it felt like, but it was as if I had a tumor in the exact part of my brain that would have given me the language to define it. The sensation was in my head, mostly, but it was separate from the pain. It felt related to light-headedness, but it wasn’t light-headedness; it might have been the opposite. Sometimes I felt like my brain was a little too big for my skull, or that it was ringing, the way ears can ring—or reverberating, like when you accidentally bite down hard on the tines of a metal fork.

I’d been having insomnia on and off, but one week my sleep was disrupted in disturbing new ways. I would start to drift off, then be jolted awake as if someone had stabbed a syringe of adrenaline into my heart. I had the terrifying thought that if I did fall asleep I would die, and that my body somehow knew this and was trying to keep me alive. The next day, exhausted, I described this experience in very vague terms to a woman I work with. She asked me whether it felt like I was being electrocuted from the inside. I was stunned. It had felt like that. After our phone call, I googled something like “electric shock feeling while falling asleep.” I found an article about brain zaps, which are typically a symptom of antidepressant withdrawal. But I have never taken antidepressants. Could it be that I was in withdrawal from my own normal brain chemistry, I wondered, my pre-pandemic levels of serotonin and endorphins? My intrinsic antidepressants? I googled the symptoms of morphine withdrawal. Anxiety, rapid heart rate, trouble sleeping—they sounded like the symptoms of anything.

Finally, I made a telehealth appointment with my doctor, who ordered a series of tests. She thought it sounded like anxiety, but I was sure there was something else wrong with me—cancer, cirrhosis. In bed at night, I sobbed into my husband’s shirt in fear. But everything came back normal. My doctor prescribed a beta-blocker to take before sleep, and the panicky feeling in my chest went away, along with the weird sensation in my skull.

At the time, I was immersed in what I thought of as the literature of despair. I read William Styron’s Darkness Visible, the novelist’s memoir of his suicidal depression. “Depression is a disorder of mood,” Styron writes, “so mysteriously painful and elusive in the way it becomes known to the self—to the mediating intellect—as to verge close to being beyond description.” While Styron is in France to receive a major prize, he feels “a sensation close to, but indescribably different from, actual pain.” Oh, I thought. I see. This pain that can’t be named is well-established. But Styron, while he was afflicted, didn’t understand it either. He felt a vague “interior doom” that drove him to the doctor for weeks of “high-tech and extremely expensive” tests, which deemed him “totally fit.”

In Suppose a Sentence, the critic Brian Dillon notes that Charlotte Brontë suffered much from loneliness and the frustration of “unfulfilled literary ambitions,” but she described her own malady as “hypochondria,” which “did not mean, or did not mean only, what it does today,” but rather referred to a melancholic condition that we now call depression or anxiety. Hypochondria, etymologically, means under the sternal cartilage—Victorians believed there was some digestive component to this condition that gave the sufferer “a visionary or exaggerated sense of pains,” in the words of Thomas John Graham’s 1826 manual Modern Domestic Medicine. The contemporary sense of hypochondria, as a restless and unfounded health anxiety, is a linguistic narrowing, and clearly pejorative: you think you are sick, but it’s all in your head and not in your sternum.

Well before COVID-19 made social distancing necessary, doctors and public-health experts were referring to loneliness as an epidemic. The size of the average household in the United States has been shrinking for decades, and more and more people are living alone. Not everyone who’s alone feels lonely, but subjective feelings of loneliness have increased. In 1985, the General Social Survey, a study that measures trends in American society, began asking participants how many people they discussed “important matters” with. That year, the most common response to the question was three. In 2004, the most common response was none. According to the neuroscientist John T. Cacioppo and the editor William Patrick, the authors of Loneliness, roughly one in five people “feel sufficiently isolated for it to be a major source of unhappiness in their lives.”

This much unhappiness seems bad enough, but loneliness also has a startling impact on physical health. Your body interprets long periods of solitude—unwanted solitude in particular—as acutely dangerous, activating a stress response that is associated with widespread inflammation along with damage to the cardiovascular and immune systems. You go into a state of heightened awareness that psychologists call hypervigilance. Your sympathetic nervous system switches on, causing surges in epinephrine and other catecholamines, as well as cortisol, a stress hormone that raises your blood sugar and blood pressure, in case you need to fight or flee. It makes you feel afraid. This response is useful in an actual emergency, but isn’t healthy or sustainable in the long term. Social isolation increases your mortality risk by roughly 30 percent, a level comparable to hypertension or smoking. It accelerates aging. And it hurts—over-the-counter painkillers such as Tylenol can be moderately effective in treating symptoms of depression and loneliness.

Of course, most lonely people aren’t aware all this is happening inside their bodies, in the dark. They just feel sad. In a 2013 poll, three quarters of general practitioners in the U.K. claimed that they saw at least one patient per day whose visit was driven primarily by loneliness. This goes both ways. My father is an internist, and at seventy-four he was reluctant to retire because his practice was his main source of social connection, his office the main place he saw people he knew apart from my mother. A number of his patients had been seeing him for thirty or forty years, and some had begged him not to stop working until after they died. One had been his first-grade teacher—he still refers to her as Mrs. Baird. During the first few months of the pandemic, he only saw patients remotely. In July, he shut down his practice entirely; given his age, it wasn’t practical or prudent to keep it open.

Cacioppo and Patrick argue that humans are an “obligatorily gregarious” species. The feeling of loneliness may thus have evolved as a signal analogous to hunger or thirst, the body’s way of increasing conscious urgency: You must eat, you must drink. You must be around people some of the time, just to feel okay.

In a graphic essay called “What Do We Lose When We Stop Touching Each Other?” the illustrator Kristen Radtke describes moving to a “driving city” at age twenty-five, a city “strung with interstates and very few sidewalks.” In this environment, “there was no accidental touching”—“no stumbling into another body when the bus jerked to a stop, no brushing a shoulder as I passed someone on the sidewalk.” She was living alone; without touching strangers, she touched no one at all.

In another essay, Radtke describes asking people what they’ve missed most about touch during the pandemic. Someone responds:

I used to wash hair at a salon. One woman would moan slightly when I touched her head. She found ways to extend her hair-washing time, which I was already extending because she obviously needed it. One day she told me, “My husband is dead and I have no children or grandchildren; you’re the only one who touches me.”

In the first piece, Radtke notes that receiving regular hugs has been shown to ease symptoms of the flu. Isolation reduces your chances of contracting a virus, but if you do contract one, the isolation may make your illness worse and last longer. “Part of the unfairness of loneliness,” Cacioppo and Patrick write, “is that it often deprives us of touch.” Psychologists call this need for touch “skin hunger.”

Before the pandemic, if your skin hunger was intense, you could hire a professional cuddler. I watched a video about one professional cuddler who noted that talk therapy is helpful for those experiencing loneliness but that “conventional therapists are not allowed to touch their clients,” so “touch-deprived” people may need a different service. The next video served up by the YouTube algorithm was a BuzzFeed video called “People Spoon With Professional Cuddlers For The First Time.” I watched that too. In these videos, the professionals, some of them employed by a company called Cuddlist, talk through the process: First, you have to sign an agreement stating that the encounter will remain nonsexual. Then, you do an activity called companioning—just sitting side by side for a bit, not touching. Dramatic music plays over the cuddling footage. A woman in a blue shirt tells her cuddler, “I feel like I always wanted a sister growing up, and so, like, I love it when people play with my hair, because it feels like having a sister.”

Watching these videos, I kept recalling specific times I’d been touched in the past. I remembered a school assembly, in second or third grade, when a boy’s shirt brushed against my arm. I remembered sitting on the balcony at a party, in my twenties, when the man I had a crush on came outside and rested his palm on the top of my head. I sometimes think touch on the face or the head is the most memorable kind of touch—maybe because our selfhood seems to emanate from there.

What has happened to the professional cuddling industry? What about massage parlors? From time to time I wonder this about some industry or other—life has changed in many ways I haven’t kept up with. I checked the Cuddlist website. Appointments were limited to virtual sessions, which sort of made me want to cry, even though I had someone to touch me in person for free.

For writers, isolation can represent a kind of glamour. We need time and space to write, of course, but not total, extended isolation. If Woolf wanted a room of her own, she also wanted to “step out of the house on a fine evening between four and six,” to join the “army of anonymous trampers, whose society is so agreeable after the solitude.” This is how writing residencies usually work: a communal meal after your day of writing. A communal reward.

For most people, social activity isn’t just a nice-to-have. Isolation disrupts our cognitive functioning and inhibits concentration—lonely people have an attentional deficit—and while it makes us more attuned to social cues, it also makes us more inclined to misinterpret them. It reduces our empathy, or as I sometimes think of it, weakens our theory of mind. We get worse at imagining others’ emotions and motivations. It becomes harder to focus, harder to make good use of our alone time. Tragically, it also becomes more difficult to make friends.

Reading a volume of Paris Review interviews recently, I took note of every time a writer mentioned strangers. Joyce Carol Oates in 1978: “I like . . . to stroll around shopping malls and observe the qualities of people, overhearing snatches of conversations, noting people’s appearances, their clothes and so forth. Walking and driving a car are part of my life as a writer, really.” Jean Rhys in 1979: “Week after week, if you never see anyone, it can become rather trying. If there’s a knock at the door, I expect some wonderful stranger. I fly to the door. But it’s only the postman.” (I feel the same way every time I hear my email ding. A major award? No, a LinkedIn notification.) Ted Hughes in 1995:

Goethe couldn’t write a line if there was another person anywhere in the same house, or so he said. . . . My feeling is that your sense of being concentrated can deceive you. . . . Fast asleep, we keep track of the time to the second. The person conversing at one end of a long table quite unconsciously uses the same unusual words, within a second or two, as the person conversing with somebody else at the other end—though they’re amazed to learn they’ve done it.

I think Hughes is right—we may think we need to be alone, but we get some kind of subconscious energy from strangers and from crowds, a complicating energy that produces ideas. They may not be our own ideas exactly, but they feel unfamiliar and therefore more original, at least to ourselves.

In one of the multiple group chats I’ve joined since the pandemic started (which some days account for my only social interaction outside of conversations with my husband), a writer asked, “When do you feel most free?” One of us answered, “When I’m traveling all day—like in the beforetimes, you know? 12 straight hours of airplanes and airports . . . obviously you lose a lot of freedom that way (where to sit, what to eat) but you also get to just sort of be a brain in a jar and read/listen to music for a million hours straight cuz there’s nothing else to do.” Another replied, “I was going to say: a delayed flight and Bloody Mary at an airport bar, half reading and half watching other passengers.”

I have not missed flying, exactly, but several months ago I read a book with a scene in a train station and felt a desperate longing to be in that scene—to have some time to kill, to drink a glass of champagne in a transit bar, alone but not alone. Why is that setting so conducive to thinking? Those are the interludes when I write in my notebook, when my mind is most alive.

The year dragged on. When it wasn’t too hot and the air quality wasn’t too dangerous—drought, wildfires, and industrial air pollution now make Denver one of the ten worst U.S. cities to breathe in—I’d go for long walks through nearby neighborhoods. I thought of these as my constitutionals, my old-timey self-care. Denverites, always extravagant with outdoor seasonal décor, were even more so in 2020, and I watched the yard decorations change behind the Black Lives Matter signs, from lingering Christmas lights to Halloween fantasias (giant animatronic spiders, lots of fake graveyards), to Christmas again, starting earlier this time.

Often on these walks, I would pass a mixed-use complex, still under construction, with apartments on the upper floors and retail space below. It sat half-completed all year; a CVS and a coffee shop were open, but most of the other storefronts were empty, some without flooring. (I called all of these “the dirt store” in my head.) They looked like ruins from another era, as if I were a tourist in an ancient city. But when I saw people in the café, eating and chatting normally, it felt more like they were alive and I was dead, like Emily in Our Town. They felt far away.

“This isn’t life,” I heard someone say early in lockdown—a maddening remark, since dying on a ventilator isn’t life, either. But I think I know what they meant—that the sameness every day, the lack of new faces, was like dreamless sleep, like lost time, not experienced life. Commuting is life, with the strangers on the train. Covent Garden is life.

It was early winter when people I know started getting vaccinated. There were signs of spring (crocus buds in melting snow) when my parents received theirs. As I write this, I’m between my first and second shots. I miss everyone I know and don’t know. Yet I’ve caught myself fearing that things will go back to normal too soon, and I won’t be ready. Why would I fear that, when I hate this way of living? I can’t explain it. My soul is glitching.