The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union hall in Birmingham. All photographs from Alabama by Isaac Diggs, April 2021, for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

One Friday morning in early March, a congressional delegation arrived at a union hall in Birmingham, Alabama. In the basement, a wood-paneled portal to the pre-Reagan heyday of American organized labor, representatives listened as Amazon employees detailed the onerous working conditions at the company’s warehouse in nearby Bessemer. By this time, their efforts to unionize the facility had become a major story. Five nights earlier, President Joe Biden had released a video statement supporting “workers in Alabama . . . voting on whether to organize a union in their workplace.” Though Biden left the Seattle-based behemoth unnamed, his comments catapulted the local organizing drive onto front pages around the world. Present at the union hall that day were an MSNBC reporter from Washington, a Reuters stringer out of New York City, and a financial journalist for a business newspaper based in the Netherlands who would be chronicling the day’s events in Dutch.

Outside the hall, I waited for the scheduled press conference with a twenty-three-year-old Amazon employee named Carrington Byers, one of the 5,876 workers who would decide whether their warehouse—whose hourly workforce is estimated to be 85 percent black—would become the first unionized Amazon facility in America. He had never been to the local Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) hall before and was skeptical of the unionization effort. Carrington liked his job as an associate in the Problem Solving Department, where he worked four ten-hour shifts a week handling misfilled orders and damaged packages. It offered endless variety, and allowed him a degree of autonomous decision-making. Still, he said, the job felt more like a temporary gig. His chief ambition was to expand his nascent business, Carrington Cosmetics, whose name was printed in a black gothic font on his gray T-shirt. He hoped to use Amazon’s Career Choice program, which provides employees who have worked at the company for at least one year with up to $3,000 in annual tuition costs, to enroll in a cosmetology program, though that field is not typically covered. “I used to want to be a music teacher,” Carrington said. “But now I want to be a cosmetics entrepreneur. And I want to get my brand into Amazon.”

Carrington explained that he was getting pushed one way on the union question at home and the other way at work. “My mom said, ‘Joe said go for it. Stacey Abrams said go for it. Danny Glover said go for it.’ ” Other relatives were on his case, too. “My grandmother was a lunch lady. I was shocked that a bunch of lunch ladies had a union. And my grandfather had a union at Goodyear.”

His employer proffered different advice. “When things got serious with the union stuff, Amazon started having classes,” Carrington told me. “Amazon was very successful in educating us.” When company-produced vote no pins were made available at the warehouse, he took a public stance, attaching one to his lanyard, which was stitched with the logo of Amazon’s Black Employee Network.

As was the custom at the warehouse, Carrington had decorated his lanyard with an array of pins depicting the company’s mascot, Peccy—a neckless orange creature with the Amazon smile for a mouth. (His name derives from management’s insistence that “Amazonians” are proudly “peculiar” individuals.) Carrington still hoped to snag the rainbow gay-pride Peccy and the Black History Month Peccy, which sported an Afro.

As the congresspeople filed out onto the front steps of the union hall, I told Carrington that he might consider putting the vote no Peccy in his pocket. He was looking forward to Representative Jamaal Bowman’s speech, and the freshman congressman, whom Carrington said he had read about on Facebook, was staunchly pro-union.

“Let’s talk about Jeff Bezos specifically for a moment,” Bowman thundered after taking the mic. “This is an individual [whose] wealth has grown exponentially while over half a million people are dead from the coronavirus.” The New York Democrat railed against Amazon’s aggressive tax-avoidance strategies and the “culture of surveillance” in the Bessemer warehouse. “They’ve created a plantation work environment,” he concluded.

Turning the company boss into a cartoon villain is a staple of union organizing campaigns. And given that Jeff Bezos’s closest cultural analogue is an actual cartoon villain—Lex Luthor, CEO of LexCorp and Superman’s bald nemesis—the tactic felt inevitable in this case. But I couldn’t help thinking this was no way to reach Carrington. He was a sunny soul, and I wagered that Bowman’s rhetoric would come across as too pugilistic.

I was wrong. When the press conference ended, Carrington looked stunned. “I’m undecided now. I am shook.”

As reporters gathered quotes, Bowman walked over to where we were standing. Very much still the middle school principal he once was, Bowman asked Carrington about his T-shirt—“Is that your cosmetics company?”—before bringing up the union.

“Over the past fifty years, the way wealth has been concentrated, you now have [a handful of] white men who own more wealth than all African Americans combined,” he said. “That’s unacceptable.” A labor union of Bezos’s black workers in Alabama would be an important step in addressing this inequality.

“But this is the first job I’ve had with this level of pay and benefits,” replied Carrington, who’d previously worked at McDonald’s and a nursing home. He noted that no one at Amazon was paid less than $15 an hour, more than twice the minimum wage in Alabama.

That’s fine for a young person still living at home, Bowman countered, but “imagine living with a partner and a kid on fifteen dollars an hour.”

Carrington nodded. He was about to sign a lease for his first apartment—in a complex that offered Amazon employees discounted security deposits and fees—and the new math of independent living was on his mind.

The congresspeople were already running late for a rally outside the facility in Bessemer, so Bowman had to take off. “Thank you for being a critical thinker,” he said in parting.

Carrington didn’t have the heart to tell Bowman that it was too late. Though ballots in the COVID-safe vote-by-mail election weren’t due back to federal vote tabulators until the end of March, he had returned his in February after receiving text messages from Amazon reading, “Vote Now! BE DONE BY 3/1!”

“I hadn’t really finished my research,” Carrington told me, “but I voted no.”

Bessemer, Alabama, was founded in 1887 by Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben, an extravagantly mustachioed industrialist. He named his city in honor of Sir Henry Bessemer, the British engineer who pioneered the mass production of steel. DeBardeleben was a devotee of the “move fast and break things” mantra more than a century before it was coined by our contemporary Silicon Valley robber barons. His favorite thing to break was labor unions—in 1894, for instance, he snuffed out a coal miners’ strike in order to keep revenue flowing.

By this time, union-busting was a venerable local tradition. The postbellum boomtown Birmingham, only thirteen miles down the railroad tracks, seemed predestined for industrial success. Its stretch of Alabama was the only place on the planet where the key inputs required for steel production—coal, iron ore, limestone, and dolomite—could be found in a single location. But as the historian Robin D. G. Kelley has pointed out, the local coal deposits sat inconveniently deep in the ground, and the city lacked a reliable source of water, another necessity. The real secret to Birmingham’s success was its inexhaustible human resources—cheap labor.

As black freedmen from rural Alabama, impoverished whites from Appalachia, and penniless immigrants from Europe poured into Birmingham in the years following its founding in 1871, industrialists turned the groups against one another for maximum profit. Once African Americans had been stripped of their political rights post-Reconstruction, they could be tasked with the dirtiest, most dangerous jobs and exploited with impunity. White workers could be paid what W.E.B. Du Bois dubbed a “psychological wage” of supposed racial superiority in lieu of a living wage. With after-work watering holes, barbershops, and sports leagues strictly segregated, labor organizing was difficult. And on the rare occasions when black and white workers joined forces, they could be crushed with convict-lease strikebreakers or state troopers.

Only after Alabama abolished the convict-lease system in 1928—the last state in America to do so—and the New Deal’s National Labor Relations Act established a federally protected right to organize in 1935 did interracial unions become widespread in the state. As a correspondent for this magazine gawked in 1937 after sitting through an integrated union meeting in Birmingham, then America’s most segregated city, “the impossible had happened.”

In Bessemer, the local U.S. Steel subsidiary finally signed a union contract in 1938, after years of stalling. Area industrialists made their peace with labor, with one executive going so far as to declare that “the poor distribution of wealth [should] be remedied.” For a time, Bessemer achieved modest prosperity as a unionized company town for U.S. Steel and Pullman-Standard, the railcar manufacturer. But American steel eventually went into decline. Bessemer’s Pullman-Standard plant closed in the Eighties, and U.S. Steel began a decades-long process of downsizing. By the turn of the twenty-first century, Bessemer was a company town without a company. A new generation came of age with no memory of its unions or its middle class—without a belief that twenty-five years of eight-hour days should be rewarded with a living wage, dignity, and maybe even a pension.

When Amazon decided in 2018 to build a “fulfillment center” on land previously owned by U.S. Steel, Bessemer was desperate. Its poverty rate was nearly 30 percent, and its median home price stood at $86,500. In order to seal the deal, the city agreed to a major concession: it would collect its customary 1 percent wage tax at the facility, but then remit between 50 and 65 percent of that revenue right back to Amazon, depending on the number of workers the company hired.

The Bessemer fulfillment center opened in March 2020, just as the pandemic began pushing online shopping to unprecedented heights. In the rush to scale up, Amazon hired a workforce that was overwhelmingly black, even though, by the company’s own estimates, this racial homogeneity could increase the likelihood of a union organizing drive. As reported in Business Insider, documents from Whole Foods, which is owned by Amazon, show that the company assesses the potential for organizing activity at its locations through a unionization-threat heat map application that tracks, among other variables, levels of workplace diversity. Work sites that score high on the app’s “diversity index” are deemed less likely to unionize, presumably because solidarity is prone to fracture along racial and ethnic lines.* With its keen attention to the racial demographics of the workforce, the heat map is a kind of twenty-first-century update of Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben’s Gilded Age labor-relations playbook.

By summer, the sweltering temperatures, constant monitoring, and production quotas at the warehouse had begun to conjure what Bowman would later call a “plantation work environment.” One black worker, Darryl Richardson, a fifty-one-year-old who had previously worked at a unionized auto-parts plant, reached out to the RWDSU to inquire about organizing. Within a few months, Darryl and a small band of activists had convinced more than three thousand of their fellow workers to sign cards authorizing the RWDSU to collectively bargain on their behalf. Amazon, however, refused to recognize the union without an election, during which it could mount a fierce vote-no campaign. Still, the organizers were confident they could rally their co-workers to their side, particularly younger employees who were less familiar with unions. If Bessemer were to become a company town once more, organizers figured, why not a union town as well?

I’d learned of the Birmingham area’s rich but little-known labor history years ago from my father, a native of the city. So in December, when I noticed a short Washington Post article with a Seattle dateline—amazon warehouse workers in alabama allowed to vote on unionization, nlrb rules—I worried that whoever wrote this latest chapter might write it wrong. One of the earliest articles the New York Times published about the Bessemer facility came out in January, and it was not encouraging: surprising soil for union roots.

I began driving up to Bessemer regularly from my home in New Orleans as the national coverage came to a crescendo. Articles and podcasts framed the union battle in the context of the country’s racial-justice awakening, the plight of essential workers during the pandemic, the future of work governed by “bossware” algorithms, and the unchecked power of Big Tech. The story blew up because it crystallized a widespread but inchoate unease about both surveillance capitalism and racial capitalism. What did the Bessemer warehouse represent, ultimately, if not surveillance capitalism as racial capitalism?

With this coverage came an outpouring of national support for the organizing campaign. A February poll showed that 69 percent of American voters were in favor of the Bessemer unionization effort. By March, after Biden weighed in and Senator Marco Rubio penned a pro-union op-ed in USA Today, that number had risen to 77 percent, including 96 percent of Democrats and 55 percent of Republicans.

Following the campaign between my visits, it seemed to me at times as though the union might pull it out. The company’s national PR effort was stunningly inept. Amazon had no response to Biden or Rubio, but lashed out at a little-known Wisconsin congressman, Mark Pocan, who assailed the company in a tweet for “union-bust[ing] and mak[ing] workers urinate in water bottles.”

“You don’t really believe the peeing in bottles thing, do you?” an official Amazon account responded. (The tweet did not deny the union-busting.)

Their spat went viral. Drivers shared photos of their own bottles as Pocan doubled down, tweeting, “Yes, I do believe your workers. You don’t?” The next day, The Intercept published leaked company documents demonstrating that Amazon was aware of the problem, and in some cases had mandated that drivers search their vans daily for “urine bottle(s).” More than a week later, Amazon issued an apology to Pocan, conceding that “drivers can and do have trouble finding restrooms because of traffic or sometimes rural routes.”

Amazon’s anti-union website, DoItWithoutDues.com, which contrasted nonunion “doers” with unionized “due’rs,” was similarly pilloried in the Twittersphere. Featured on the page was a man giving two thumbs up and wearing an Amazon lanyard studded with Peccy pins. Ostensibly a Bessemer warehouse worker, he had a suspiciously Pacific Northwestern pallor and wore a hat bearing the logo of the Ivy League Harvard Crimson football team instead of the SEC’s Alabama Crimson Tide. Farther down the page, a giddy black man could be seen leaping into the air. Internet sleuths soon identified the image as part of a free stock photo called “Excited african-american couple jumping, having fun on orange background.” Below him was an anomalous image of a corgi DJing, accompanied by text suggesting that instead of wasting money on union dues, workers should buy “dinner,” “school supplies,” and “things you want.” It seemed a particularly tone-deaf pitch for employees in Alabama, a so-called right-to-work state where paying dues would be optional even if a union were formed.

Yet in Bessemer, I could see that even as Amazon’s national campaign was becoming a punch line, its on-site misinformation blitz was no laughing matter. Ultimately, the only place where Americans seemed to oppose unionizing the Alabama Amazon warehouse was in the Alabama Amazon warehouse itself.

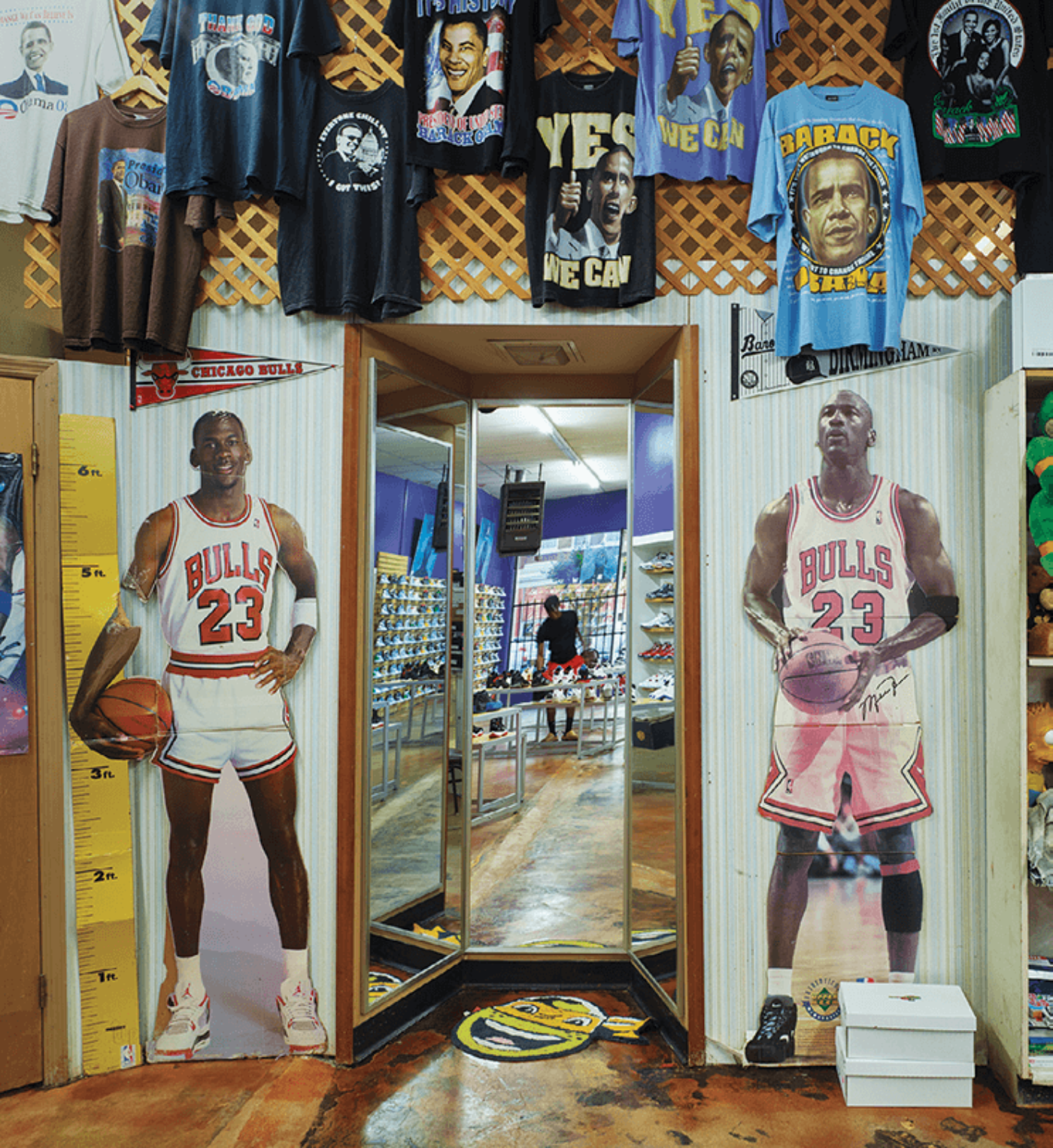

Everybody in Bessemer seems to know somebody who works—or at least worked—at Amazon. At Memory Lane, an independent sneaker store in Bessemer’s struggling commercial district, I met Ananias Ware, an eighteen-year-old with dreadlocks and braces. I asked him whether he knew anyone who worked at Amazon. “The whole of Bessemer basically works there,” he chuckled. But people quit all the time. “They feel like they’re slavin’,” he said. A study by the National Employment Law Project estimated that turnover in some Amazon warehouses exceeds 100 percent per year, meaning that the annual number of individuals who leave exceeds the total workforce.

Ananias himself worked at Amazon last summer, between semesters of community college. He couldn’t stand the warehouse’s stifling heat, but Amazon paid better than the sneaker store, so he worked there just long enough to buy a used car. “It’s good money, [but] when I started feeling like a robot, I left.” He purposefully quit on good terms, resigning after giving his two weeks’ notice. “If I feel like I need to come back to make more money, I can,” he told me.

Members of Ananias’s generation are often described as digital natives. It’s a compliment—and well earned for their effortless technological fluency. But they’re also plutocracy natives, tech-oligopoly natives, and gig-economy natives who have never known an America where profitable companies are expected to offer stable, remunerative careers. Which is why, perhaps, the union divide in Bessemer felt generational. Older people of all races and political persuasions were reflexively pro-union. Younger people, even progressives, weren’t exactly anti-union but held no strong opinions. And all of a sudden they found themselves as the protagonists in the most significant union organizing drive in decades.

The union divide in the Deep South is often portrayed along racial lines, between pro-union African Americans and anti-union whites. But the generation gap I sensed seemed not to respect racial boundaries. At W.T.’s Restaurant & Lounge on the outskirts of downtown, the sign posted above the bar read,

in this place we always

salute our flag

support our troops

buy american

say “merry christmas”

say “one nation under god”

respect our law enforcement

if this offends you there’s the door

The establishment seemed particularly hung up on the Christmas thing; they still had their tree up, lights and all, in March. When I asked the bartender, a late-middle-aged white woman, what she thought about the union drive, she told me plainly, “I don’t see why they wouldn’t want it.” A pale, portly retiree sitting to my right piped up, “I was raised on union money. My daddy was a union steelworker.”

Assumptions were different at a vegan soul-food joint across town called Good Health To Be Hail. As I waited for my barbecue jackfruit sandwich to arrive, I noticed a wall calendar from the harrowing lynching memorial in Montgomery, the state capital, and a shelf full of anticorporate documentaries on DVD, including Food, Inc. and Sicko. A black graduate student who stopped in for takeout told me she’d been following the union fight on Twitter. She’d seen awful stuff, including the leaked documents about delivery drivers peeing in bottles. But she didn’t have a strong opinion on the union question. “I think that I’m not really informed,” she said.

The restaurant’s tall, fit cook told me that a few weeks earlier, a group of activists had come by and asked whether they could put up a pro-union sign out front. “I told them I’m not necessarily for it or necessarily against it, so they can use the edge of the property.” When I left, I spotted the red-and-black lawn sign—our community supports amazon workers. vote union yes!—out by a utility pole that marked the divide between the restaurant’s parking area and the used-car lot next door.

Younger workers at the warehouse had also come to the union question with few strong opinions, an ambivalence that the company eagerly exploited. I met one twenty-four-year-old Amazon packer sitting at the horseshoe bar of the Bessemer Applebee’s. She had just finished a shift and was nibbling on a quesadilla and nursing a bright mango-tequila drink. Her daughter was asleep at a friend’s grandmother’s house. It was nearly ten o’clock, and it would take her almost an hour to drive back, so she figured it was best to let the kid sleep through the night and pick her up in the morning.

When I asked her about the union campaign, she dismissed the mandatory classes that the company had been running as a waste of time. “They just tell you what happens if you vote yes, what happens if you vote no,” she said. It wasn’t a tough call; she was a no.

I asked which argument had swayed her against the union. “I really don’t know,” she said. “I just don’t know why Amazon would lie to their employees. I don’t understand that.”

An Amazon truck leaving Bessemer

I had been told by one anti-union employee that if I wanted to visit the fulfillment center, I should go to the main entrance of the warehouse and ask for a tour from HR or the Bessemer police officers who manned the facility 24/7. (It was later revealed that though they wore their official uniforms and drove marked cars, the off-duty officers had been hired by Amazon as a private security force.)

The next morning, I walked through the front door, gazed up at the giant American flag suspended from the rafters, and took in the deafening din. The clanking and wheezing of the conveyor belts echoed through the twenty-acre warehouse. I explained to a security guard that an employee had told me to come in for a tour and that I would need a loaner badge. I handed over my driver’s license, which was passed around among various security guards—all of them black—until finally a white man named Patrick Timmins approached. He wore a Loss Prevention department fleece and a Crimson Tide football lanyard where I spotted a vote no Peccy. He walked me outside, where it was quieter.

“I don’t know which employee told you what, but we can’t do any tours, especially at this time,” he said. Patrick handed me my license and told me politely but firmly that I needed to leave the premises. I offered him my elbow for a COVID-safe send-off. “No, sir. Can’t do that. It violates the six-foot rule.”

Amazon’s national PR team never publicly acknowledged that the vote-no campaign existed at all. But inside the warehouse, workers told me, the company’s position was clear. “They want us to vote no,” one anti-union worker told me approvingly. “They’re plastering it all over the building.” Banners and signs had been put up everywhere, including in bathroom stalls, reading we win as one and unions can’t. we can. Workers were bombarded with anti-union text messages and flyers reminding them to vote no. Out front, Amazon had built a tent around a postal drop box that had been installed at the company’s request. A banner was hung across its side bearing the vote-no campaign slogan speak for yourself! and depicting a row of raised-fist emojis in a variety of skin tones holding up their ballots, united in a collective uprising against collective action.

Amazon’s most effective union-busting tactic was requiring employees to attend so-called captive audience meetings. The presentations were a study in psychological projection. Amazon, a publicly traded for-profit corporation that maximizes shareholder value and refers to its employees as “associates,” was presented as a “family.” Meanwhile, unions—nonprofit organizations whose members call each other “brother” and “sister” and who elect their own leaders—were framed as businesses run by “bosses.” The workers were told that the union, being a business, had come to Bessemer only to squeeze a profit out of them, whereas Amazon, being a family, had arrived to aid a struggling community.

Although research clearly shows that unionized workers take home more in pay and benefits than their nonunionized peers, Amazon suggested that workers could end up losing money thanks to dues and collective bargaining, during which, as one company text message put it, “Everything is on the table.” The legal requirement that the company bargain “in good faith” with its employees—i.e., it could not just show up at the negotiating table and start at $7.25 an hour and no health-care coverage—was never discussed. “They’re already taking enough money out of my check,” a twenty-eight-year-old with braids and a hoodie told me, explaining why she had voted no. Another young black no-voter I met in the warehouse parking lot suggested that it was up to each of Amazon’s more than half a million American hourly workers to negotiate their benefits individually. “I feel like if you think the benefits aren’t good, you have to go ask someone for better benefits,” she said. “A lot of people are just going for handouts.”

Older, pro-union workers found themselves forcefully sidelined in the company’s classes. Glenda (she asked that her last name not be used), a fifty-eight-year-old grandmother who worked in the Stowing Department, spoke up to try to expose the consultants’ and managers’ sleight of hand. She had previously been employed as a unionized secretary at U.S. Steel, where she had seen her hourly wage nearly double over fourteen years on the job. As for the younger workers at Amazon, she said, “They come from fast food and don’t realize they can have it so much better than they have it now.” Glenda recalled one slide from the classes that listed scheduled pay raises through thirty-six months of employment. “I asked, what happens after thirty-six months? Because with a union you’ll have a contract and you’ll know what the raises are through the contract.” At U.S. Steel, she said, contracts typically ran five years and the raises that were written into them were legally binding, unlike Amazon’s PowerPoint slides. How could anyone take these slides seriously, she wondered, coming from a company that had revoked their two dollars an hour in COVID-19 hazard pay just as the virus started to spike in the region? Like many workers who asked pointed questions during the presentations, Glenda found herself silenced by the instructors. “I got bombarded with the people who were there conducting this meeting,” she said. “They shut you down quick.”

Glenda told me she had heard rumors that the warehouse might close if the union were to win the vote. A leaked Amazon training video from 2019 explained precisely how managers might start such rumors without violating the letter of federal labor law. “You would never threaten to close your building just because associates joined a union,” a computer-generated, racially ambiguous female Amazon manager cheerfully advises in the film. “But you might need to talk about how having a union could hurt innovation, which could hurt customer obsession, which could ultimately threaten the building’s continued existence.”

All over the fulfillment center, pro-union voices were silenced while those of no-voters were amplified. Near the main entrance, flatscreen monitors on a red carpet were cordoned off with a velvet rope. The screen on the left showed testimonials from employees who had pursued health-care and IT jobs through the company’s Career Choice program. On the right was a Black History Month salute to the first African-American woman to ever serve as a U.S. ambassador. Taking center stage on screen was a certain cherubic Amazon worker with a speech bubble next to his mask-covered mouth: “We don’t need a union. . . . We have all the necessities and everything we need to be cared for here.” The quote was signed, “Carrington, Associate.”

On the morning of Friday, April 9, the election results were announced—the union had been defeated by more than a two-to-one margin. I heard the news while driving from Bessemer to Ashville, Carrington’s hometown on the other side of the Birmingham sprawl, where he lives with his mother, stepfather, and two younger half sisters. When I arrived at the cramped, cluttered house a little after noon, both parents were at work, and the girls, who were attending virtual school, were jumping on a trampoline and riding a bike, respectively. As the older sister explained to me with a grown-up’s confidence, virtual school didn’t entail much live instruction. It consisted mainly of assignments with due dates—as long as you turned them in, teachers left you alone.

Carrington was relieved that the election was finally over. He told me that his presence at the union hall a month earlier had not gone unnoticed by his superiors. A local reporter for the news site AL.com took notes on Carrington’s sidewalk conversation with the congressman and briefly interviewed him afterward. (Carrington told me he’d thought the man was a Bowman staffer.) That Sunday, AL.com published an article with the headline for one amazon bessemer employee, a wavering vote. It described Carrington as having “second thoughts.”

“A manager asked me why I went to the union hall,” he said. “I had to explain to him all week that I had already voted no.” Some co-workers were also curious after seeing the article. “There’s a side A, B, and C,” Carrington explained to them. “All you heard was A. You never heard B. And C is the whole truth. So think, think, think, think, think.”

Even though it ruffled some feathers, he had no regrets about having gone to the press conference. “It felt good, honestly, to hear somebody else’s opinion other than what Amazon had already imprinted into my head,” he said.

Many of the problems detailed by the congresspeople focused on the ways in which worker productivity is strictly monitored. When he returned to work, Carrington observed his colleagues’ behavior. Frankly, the surveillance seemed justifiable to him. “We have people in there who’d rather be in the bathroom on their phone for fifteen to twenty-five minutes. Dozens of packages could have been processed in that time you were in the bathroom on your phone.” As an entrepreneur, he sympathized with Amazon. “If I was the boss and it was my makeup company, I would be ticked off if somebody spent this much time on their phone and a customer didn’t receive their order on time.”

The tempest at work soon blew over. To help patch things up, Carrington brought in some pasta his mother had made him for his birthday. “My mom made so much lemon-pepper alfredo that I ate on that all week. I even packed some up and gave it to some of my managers. They were like, ‘Whoa!’ ”

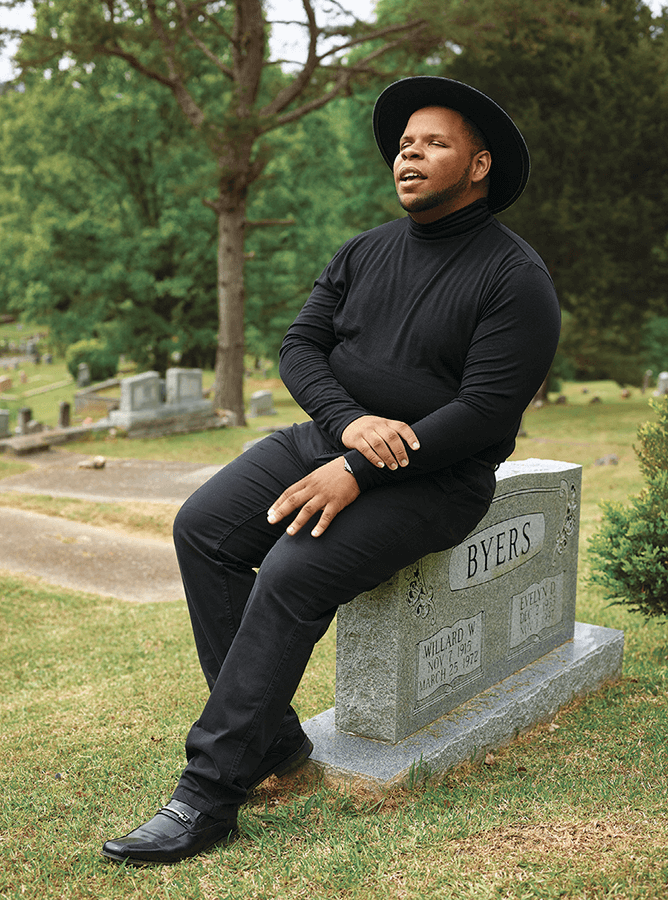

This was the last day of Alabama’s mask mandate, and the local high school was hosting an outdoor prom. Carrington had a makeup appointment that afternoon for one of the students, but he made time to give me a tour of his hometown, population 2,380. Sitting shotgun, he directed me to the high school band building, where he had learned to play the saxophone; the historic courthouse, where he’d just filed the paperwork to incorporate Carrington Cosmetics; and the hilltop cemetery, where his family had been buried going back to Reconstruction.

At his direction, I parked in the gravel lot at his church—a corrugated-metal structure with a redbrick facade. It was Friday and the building was empty, but as a veteran sax player for Sunday services, Carrington had a key. As we entered the sanctuary, he proudly pointed out the whitewashed wooden cross above the pulpit that his uncle had hewn by hand and the music stands in the corner where his stepdad led the band.

Technically, Carrington confessed, he didn’t attend church anymore. On Sundays, from 7:45 am to 6:15 pm, he was in the warehouse, on the clock. But he still tithed, contributing 10 percent of his after-tax income—about $40 a week.

Carrington at Ashville Cemetery

“There’s a saying that what you do for God and do for his house,” he told me as we walked back to the car, “he will bless you back tenfold, whether that’s through money or a job promotion.”

To me, it seemed kind of like paying union dues. He disagreed with a vehemence that took me aback. “These fools taking money from me. What good does that do me?” It sounded like the voice he’d used to tell his managers that he hadn’t flipped.

As we drove on, Carrington indicated his grandmother’s house, slightly larger than the home he shared with four family members, halfway up a hillside. He thought it best not to bother her. They’d been through the union question so many times, and the gap between their generations seemed unbridgeable. “You are a product of where you come from and of who raised you,” he mused. “A lot of my family grew up in a time when the union was an amazing thing. My grandma talks a good bit about being a lunch lady and being in the union and being the one who took care of the cases if somebody had a problem. I talked to her about it. Some people, they’re just never going to change.”

Grandma didn’t get it. Working at Amazon wasn’t like being a lunch lady. It wasn’t like his job at McDonald’s or at the nursing home, either. Amazon wasn’t a dead-end job; it was a gig—a stepping-stone, really. “Everybody there is family-based,” Carrington told me. “Out of everywhere I’ve worked, this is the only place where my managers are helping me, guiding me through my ventures that I want to pursue outside of Amazon. This is the only place I’ve ever been where they want you to become somebody.”