“Ramona Gardens Projects, Boyle Heights, Los Angeles,” by Gregory Bojorquez. Courtesy Galerie Bene Taschen, Cologne, Germany

los angeles

49% hispanic

biden 71%, trump 27%

When I was growing up in Los Angeles, I didn’t call myself “Latino,” and neither did anyone else I knew. My father was born in a verdant village in Guatemala’s banana-growing region; my mother was raised in Guatemala City. In the California of the Seventies, when hyphenated ethnic identifiers were all the rage, I described myself as Guatemalan-American. In 1980, I marked the box labeled “Hispanic” on my family’s census form, attaching that term to my name for the first time. In college, I took a course called Spanish for Spanish Speakers, placed an accent over the e in my given name, and hoped to embrace my inner guatemalteco. Later I lived in Mexico City and learned how to cuss like a local chilango, which mortified my mother. I became the editor of a bilingual newspaper, and then a novelist preoccupied with all things Latin American. Only after I published my third book did my father reveal that my late grandmother, a lifelong domestic worker, had never learned to read or write. By that time I was Latino, at least according to the house style adopted by my then employer, the Los Angeles Times.

The many English dictionaries I own tell me that the term “Latino” refers to a person who has roots in Latin America, but that’s a huge spectrum of humanity: descendants of more than a dozen countries and territories; Jews, Catholics, Muslims, and Mormons; people with blond hair and those with dark skin; folks whose first language might not be Spanish but Quechua, K’iche’, or even English. It’s a term so capacious that it can mean almost anything, and it can feel empty to those of us forced to use it. If you ask so-called Latinos about their ethnicity, they’ll usually say something like “I’m Mexican” or “I’m Cubano,” or use any number of other national or regional identifiers.

But when you hear a label repeated so often, you can’t help but get used to it. I married into a Chicano family, and my wife and I have three children. For them, Latino or Latinx makes more sense than Mexican-Guatemalan-Chicano-American. In fact, in this age of resurgent white supremacy, I’ve begun to wonder whether Latino might have more significance than I’d understood. As with this country’s other major ethnic and racial labels, its true definition was born not of biology or geography but of a common experience relative to white identity. Latino was coined to describe something a white person wasn’t. Today, a certain kind of white person attaches a sense of foreignness to us; we, in turn, continue to resist the cultural erasure that accompanies assimilation.

In the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election, a cast of mostly white commentators struggled to define the term in an attempt to make sense of Latino voting patterns. According to one national exit poll, the shift in the Latino vote was modest: 31 percent of us voted for Donald Trump, three percentage points more than in 2016. But in Florida and southern Texas, Trump gained ten to twenty points or more among Latino voters, and those dramatic swings dominated the postelection conversation. In the days after the election, whenever I opened a web browser, I could hear the annoyance, feel the condescension. Black people voted overwhelmingly for Biden because they could see that Donald Trump was a racist, the pundits argued. But more of you Latinos voted for Trump than in 2016, even though it was your children he rounded up, your fathers he labeled rapists and murderers. Even Barack Obama called us out, saying that “evangelical Hispanics” had given more consideration to “their views on gay marriage or abortion” than to Trump’s racism or his “undocumented workers in cages.” Following the election, several outlets sent reporters to interview Latino voters. After listening to our conflicting points of view, journalists threw up their hands and declared us a mystery, a conundrum, and a nonentity. As more than one commentator put it: “There is no such thing as the Latino vote.”

In one sense, this is unquestionably true. Like all labels, Latino is to some extent a fiction, a story we tell about ourselves. But what, if anything, does this story mean? In December, I set out on a nine-thousand-mile road trip across the country, aiming to visit as many Latino communities as I could, a solitary trek that would take me across the Snake and Mississippi Rivers, through icy deserts and over lonely mountain ranges, and into quarantined cities where various dialects of Spanish and Spanglish were spoken. I wanted to find out whether a term that describes so many different people in so many different circumstances still had something to say.

woodburn, oregon

57% hispanic

biden 58%, trump 42%

I left Los Angeles with an ample supply of face masks in my glove compartment and headed north on Interstate 5, along the same route countless farmworkers take to the Pacific Northwest, following the harvest of strawberries, lettuce, and hops. Not long after I entered the San Joaquin Valley, signs in support of the forty-fifth president began to appear along the highway. I considered pulling off the road to seek out one last meal of good Mexican food before leaving California, but there seemed to be nothing but Taco Bell on offer. A fog began to roll in after I crossed into Oregon. As night fell, a full moon rose over a tableau of misty mountains and the silhouettes of tall Douglas fir trees. It looked to my weary guatemalteco eyes like a strange, menacing land.

I headed to the farm town of Woodburn because it’s a small island of Mexican culture in the great white sea of Oregon. The nineteenth-century pioneers who founded Oregon barred black people from settling in the state, and even now it is just 2 percent black and 13 percent Latino. Portland, thirty miles to the north of Woodburn, is one of the whitest major cities in the country. The Mexican families that first came to Woodburn and the surrounding Willamette Valley in the Forties were itinerant farmworkers. During World War II, the Mexican laborers of the Bracero Program were hailed for rescuing the state’s wheat and fruit crops. Today, an estimated 98 percent of farmworkers in Oregon are Latino.

Woodburn is a town of humble wood-frame and brick structures. Teresa Alonso Leon and her family arrived in the late Seventies and early Eighties, after long journeys from the mountains of Michoacán, Mexico. I first met her in 2019, in an old office building that had been converted into a food court. On my return, with the pandemic at its height, we spoke on the phone. Alonso Leon was born into an indigenous Purépecha family, and Spanish was her family’s second language. Some of her earliest childhood memories are of dancing in Purépecha festivals. “My mom said I learned to dance at a super young age,” she said. Latino and Latinx, terms whose etymology is European, erase the indigenous identity of people like her, and of millions more people, like me, with hidden indigenous roots. But Alonso Leon has learned to embrace the term: when we spoke, she was organizing a meeting of Latino elected officials.

I asked Alonso Leon if there was a place in Woodburn that was special to her, and she directed me to the oak trees growing on Settlemier Avenue, near downtown. Then she told me the story of how she first came to see those trees. Her mother had immigrated to Oregon, leaving Teresa behind in Michoacán. A few months later, an aunt took Teresa north, but the authorities in Tijuana separated them, and Teresa ended up in the back of a patrol car. “I’ve never shared this publicly before,” she said, fighting back tears. When she finally arrived in Woodburn, she looked out another car window and saw the trees on Settlemier Avenue. “Those trees meant I was closer to my mom, who I loved more than anything in the whole world.”

In Oregon, her parents picked berries and other crops, and the family lived in a ramshackle home on the edge of town. The possibility of detention and deportation hung over her childhood. “We’ve been traumatized even before the Trump Administration,” Alonso Leon told me. Starting in the Fifties with Operation Wetback, immigration agents chased workers through the berry fields, and in 1978 they conducted a five-day raid during the local cauliflower harvest. As a young girl, Alonso Leon learned English and acted as an interpreter for her parents, and she saw them humiliated and exploited by white people. “I chose what to translate back to my parents,” she said. “Because there was so much racism.” Like countless immigrant children, she absorbed the sting of the insults directed at her mother and father.

Alonso Leon, now forty-six, transformed this humiliation into the kind of hypercitizenship I’ve seen before among the progeny of Mexican immigrants. She went to college, became a U.S. citizen, and landed a job at an Oregon state education commission. She was appointed to the Woodburn City Council in 2013, and later persuaded her family to dance in Woodburn’s annual Fiesta Mexicana parade. “We’re going to showcase our cultura,” she told them, and they performed the baile del torito, the bull’s dance, as her brother played music from the back of his pickup truck. In 2016, she was elected as a Democrat to the Oregon State Legislature.

Her parents are nearing retirement age, but still do farmwork in nurseries. They became U.S. citizens “because they both wanted to vote for me,” she said. “When they saw me win, that was huge.”

wilder, idaho

74% hispanic

trump 62%, biden 28%

The road to Idaho took me through the woods of central Oregon, past the ashy ruins of dozens of homes destroyed by recent wildfires, then across the sagebrush of the eastern Oregon desert and into decaying, one-stoplight towns with billboards offering help to the agnostic and the suicidal. After eight hours of driving, I reached the town of Wilder, in western Idaho. The same circuit of itinerant work that brought Alonso Leon’s family to the Northwest brought Mexican families here as well.

Back in 2015, Wilder elected an all-Latino city council, but no one really noticed—until a reporter from Boise visited and told them they were the first municipality in the state to do so. Latino people in this part of the country are proud of their roots but eschew identity politics. Wilder, a town of about 1,500, is far away from the urban centers of Latino political power and expression. Their neighbors are, generally speaking, a deeply conservative lot. “I know that not everyone agrees with me being here,” the town’s Mexican-American then mayor, Alicia Almazan, a beautician by trade, told me in 2017. “But it’s not because I’m Hispanic—it’s because I’m a woman.” After a slew of stories in the national media about Wilder’s all-Latino city council (including one I wrote), Almazan was trounced in her 2019 bid for reelection.

Near the hop fields on the outskirts of town, I met a twenty-eight-year-old employee at an auto-parts store, Gerardo Anguiano, whose family came to the United States from Colima, Mexico. Anguiano told me he couldn’t vote because he was “only a resident.” But if he could have voted? “Trump,” he said. It seemed he’d been influenced by his friends, many of whom own small construction businesses and feared a Democratic tax hike. “I would admit he’s racist; he talks a lot of smack. I don’t think he’s fit for office,” Anguiano said. “But the way the country is, you never want a lot of money taken out of your paycheck. I guess everyone is looking after themselves.”

American individualism is a powerful thing: You can use it to fill your wallet with honestly earned U.S. dollars, and own a pedacito of the American dream. It can even persuade a Mexican immigrant to support a man bent on deporting as many Mexican immigrants as he can. Latino identity, like those of other American ethnic groups, is created by the attraction to and repulsion from self-interested Anglo-Saxon Protestant values. We see white people living an orderly, safe, and affluent existence, and many of us want to be like them. According to a Pew survey, 11 percent of people who could identify as Latino choose not to.

Anguiano told me there was one thing that bothered him about the Trump years: more people in Idaho telling Latinos they shouldn’t speak Spanish in public. Why should it concern them? When you live with the contradictions of being Latino, it’s possible to be an individualist immigrant and still take pride in your culture. Anguiano was proud of Mexican cooking, as I learned when I told him I was going to have dinner at a restaurant two blocks away. He frowned. “That’s more of a white Mexican” place, he said, suggesting one on the other side of the railroad tracks instead. When I visited this eatery a few minutes later, I discovered it was a restaurant, grocery store, and meat market all in one. A black road worker who entered remarked, “They’ve got real chicharróns here.”

tierra amarilla, new mexico

71% hispanic

biden 66%, trump 33%

What to call the people now known as Latino has been debated for more than four hundred years. The Spanish settlement of what is today the Southwestern United States in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries gave birth to ethnic identifiers such as Tejano and Californio. Then the United States conquered the territory in the Mexican-American War. “Mexican” became an insult used by English speakers to denigrate the locals with Spanish surnames, denying them the social status of white Americans. In 1929, the first major national organization of Mexican-American activists took the name the League of United Latin American Citizens precisely because they wanted to distance themselves from that label.

“Mexican” became a racial category for the first (and only) time during the 1930 census, as officials grappled with what to call the darker-skinned people with Spanish names living in the United States. Many Mexican Americans, meanwhile, were ambivalent about their own racial identities. Latin American people have never quite fit into the country’s established legal racial categories. In the landmark 1946 school-desegregation case Mendez v. Westminster, a lawyer for a group of Mexican-American families argued that children of Mexican descent were white and therefore could not be separated from white children. (The judge ruled in their favor on different grounds: the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause.)

My birth certificate lists both of my parents as “Caucasian,” because in the thinking of the Sixties, there was no other category in which to put them. That same decade, the term “Chicano” (an old pejorative) was gaining currency as a hip alternative to Mexican-American, much as Latinx is spreading among young people today. “A Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself,” the columnist Ruben Salazar wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 1970.

Ten years later, in the aftermath of social movements during which Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans and other Spanish-surnamed people demanded civil rights, the Census Bureau created the pan-ethnic category “Hispanic,” an English adjective that describes Spanish-speaking people. Around the same time, activists started using the term “Latino,” a Spanish word derived from the longer latinoamericano. Hispanic became a box you checked on a form, whereas Latino rolled off the tongue and was a statement of unity among immigrant groups.

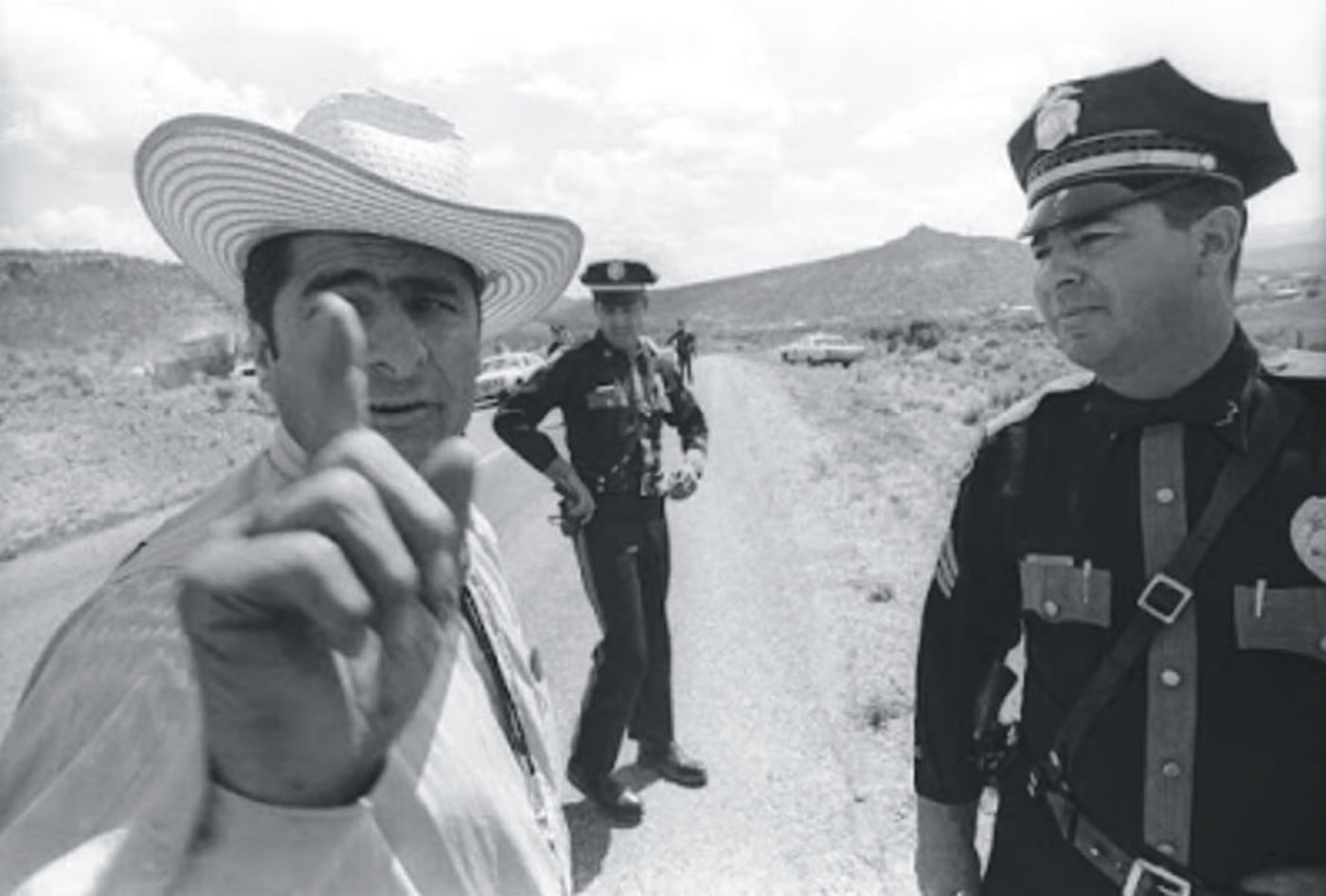

In New Mexico, however, where Spanish identity predates the immigrant flows of the twentieth century, Hispanic is still the preferred term, because it expresses the cultural ties locals have to Spain. New Mexico was the region of the modern-day United States most incorporated into the Spanish Empire, and Hispanos was the term the conquerors used to distinguish themselves as a race apart from the Zuni, Acoma, and other indigenous peoples living among them. Many property deeds in northern New Mexico can be traced back to the vast land grants the Spanish crown issued to Hispano settlers. After the U.S. conquest, the land grants were systematically taken over by Anglo settlers and the federal government. More than a century later, the charismatic, Texas-born preacher Reies Lopez Tijerina arrived in New Mexico to demand that the United States government restore the land to the descendants of the original Hispanos. His movement climaxed with a brief takeover of hundreds of thousands of acres, followed by an armed raid on a courthouse in Tierra Amarilla in 1967.

When I arrived there, I found a ghost town of locked government buildings and crumbling stores. The poverty rate in the surrounding county is 22 percent, double the national rate. It was a Sunday, but the Catholic church had been shuttered because of the pandemic. I knocked on a few doors, rattled a few gates. I found a faded tribute to the TA Raiders—Tijerina’s vigilantes—painted on the wall of an abandoned storefront, but no one was around. Finally, on the highway at the edge of town, I saw cars pulling up to Henry’s True Value, an all-in-one liquor, hardware, and fishing-supply store. Inside, I found a young clerk with tousled hair standing behind the counter, brown eyes visible above his face mask. In between customers, we fell into a conversation about local history.

“There are still people pretty animado about the land grants and all that stuff,” C. J. DeYapp told me, speaking in a warm and lilting New Mexican accent. “It doesn’t turn into a big thing like it did, but they still have that emotion.” DeYapp, twenty-six, works at the store his family owns and is the grandson of its founder, the late Henry Ulibarrí, who was a leader in the community. “There was a time he was considered the godfather of TA,” DeYapp said of his grandfather. He told me that the TA Raiders tried and failed to persuade his grandfather to join their cause. Tijerina went to prison; the elder Ulibarrí stuck with his store.

When I visited, beer and shooters of Jack Daniels, 99 Cherries, and other liquor made up most of the sales. DeYapp seemed to know everyone in town. His roots run wide and deep. “As far as my nana’s side, they for generations have been in Cebolla,” a town twelve miles to the south, he said. “My tío Rick is the local electrician,” he added, and his tías live and work in the surrounding settlements; one does nails in Santa Fe. His grandfather’s surname is Basque; a Juan de Ulibarrí led a Spanish expedition to the area in 1706.

DeYapp didn’t want to tell me how he had cast his presidential vote. But when I pressed him about the issues that defined the campaign, he expressed concern about Biden’s economic plans. “You look at the taxes part of it, it’ll impact even the store.” DeYapp said he’d heard that Biden wanted to raise the federal minimum wage “to like seventeen bucks or something.” (The figure Biden proposed was $15, but that’s still far above the $10.50 New Mexico adopted at the beginning of the year.) “We would have to close. We couldn’t pay out seventeen to everybody . . . That’s just too much.” DeYapp didn’t mention Trump, but it’s clear that some of his arguments have resonated. I left Henry’s True Value and stepped back into the piñon-scented desolation of Rio Arriba County.

Ultimate Flavor, by Narsiso Martinez © The artist. Courtesy Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles, from Washington’s State Art Collection

el paso county, texas

83% hispanic

biden 67%, trump 32%

The Rio Grande flows south from Rio Arriba County toward El Paso, my next destination. Trump last visited El Paso in August 2019, days after a twenty-one-year-old man from the suburbs of Dallas murdered twenty-three people at a local Walmart. In an online manifesto, the shooter said he feared the power of the “Hispanic voting bloc” and the “great replacement” of white people. The Walmart reopened three months later. I stood in the parking lot where the shooter had begun killing brown-skinned people and watched as a steady stream of shoppers filed through the same entrance he had used. Inside, just past the glass doors where security cameras captured him carrying a WASR-10 semiautomatic rifle, I found racks of women’s polyester parkas and boxes of doughnuts for sale. The light was fluorescent and stark; it seemed to mock the dead.

I first witnessed the resurgence of anti-immigrant ideas in the Nineties, when California voters approved Proposition 187, a ballot initiative that denied nearly all public services to the undocumented. Since then, a discourse of white fear has spread across the United States. In the eyes of a certain kind of white American, Latinos have become a darker and more menacing people. The right-wing media equates Latino immigrants with criminals. The border wall has become a central element in the construction of modern white American identity. To be white is to live on this side of the border—and to need the wall to protect you from the non-white masses to the south. Dreams of the border wall gave birth to Trumpism, and helped fuel the growth of the white supremacy that was on display in Charlottesville, Virginia, and during the Capitol insurrection.

After the El Paso shooting, the historian David Dorado Romo, who lost a friend in the attack, wrote a piece for the Texas Observer that contextualized the massacre within the state’s long history of racial violence. Romo suggested that I meet him in the old El Paso neighborhood of Duranguito. “This was the First Ward, the Mexican quarter,” Romo told me. We stood next to a fenced-off stretch of buildings. Four blocks had been slated for demolition to make way for a new arena. Crews had punched holes in the century-old brick walls. “Part of what they’re doing here is eliminating those roots,” Romo said. “You erase history, then you can deport bodies.”

One of the last holdouts in Duranguito is ninety-three-year-old Antonia Morales; nearly everyone else has been evicted or accepted payments to move out. She is white-haired, spry, and sometimes salty of speech, and like many locals, she is a true child of border culture. Morales was born in Columbus, New Mexico, twelve years after that border town was raided by Pancho Villa, then moved to Ciudad Juárez, and finally to El Paso. Duranguito was a tough neighborhood when she arrived in the Sixties. “I’m going to fight for my community, because I worked hard to live in a clean and safe community,” she told me. “I’m not moving from here.” When she first got to the area, El Paso and Ciudad Juárez formed a single town with a river running through the middle, and people crossed the border bridges with ease. Sometimes the border agent didn’t even bother to check your papers, she told me. “He would say, ‘Hi, how are you?’ ”

Romo told me he isn’t particularly fond of the term “Latino”; he prefers to call himself fronterizo, a person of the border. “We’re not immigrants; we’re transnational residents,” he said. “We’ve been going back and forth for more than one hundred years. That’s the nature of this place. You’re a hybrid of sorts.” Over the past two decades, however, the border has become less fluid, as one crackdown after another has filled El Paso with officers working for the Border Patrol, the DEA, and other law-enforcement agencies. The Trump Administration opened a large migrant detention camp near El Paso that held more than six thousand children, which became a focal point for the city’s immigrant-rights movement.

El Paso has a long history of Mexican-American activism and cultural pride; “pachuco,” a term used to define a style of clothing and an attitude that defies Anglo mores, was invented in El Paso–Juárez. The lawyer-activist Oscar Zeta Acosta and the journalist Ruben Salazar were born here, and both became Chicano martyrs after they died under suspicious circumstances in the Seventies. El Paso’s us-against-the-world temperament has long been used to support progressive and Democratic causes.

starr county, texas

96% hispanic

biden 52%, trump 47%

I drove more than six hundred miles to the southeast, past brushland and dry riverbeds, across one of the empty quarters of Texas, a region without cattle or even roadkill. The border was to the right, and sometimes I could glimpse it, or sense it in the landscape: a green canyon with a brown stripe running through it. This scrubland was largely unpopulated when the border was drawn more than one hundred and seventy years ago, and it remains hostile territory today.

After two days, I reached the oasis of the Rio Grande Valley, and the metropolis of Laredo, where fleets of tractor trailers line up at massive, multilane border crossings. The valley is a deeply segregated place, and suddenly the faces on the side of the road were almost entirely Latino, or Tejano, as the locals would say. Two more hours on the road and I was in Starr County, which hugs the border. In 2020, it made the largest swing to Trump of any county in the United States.

Many people in the Rio Grande Valley believe the region’s well-being is tied to the state’s oil and gas industry. Nearly everyone I talked to in Rio Grande City was afraid that Biden’s environmental policies would wipe out their livelihoods. I stopped to get my car serviced, and the man running the shop mentioned the plight of the oil industry. Another customer who worked in the oil industry told me he was worried about Biden’s policies. Neither one of them had voted.

In Rio Grande City, I came across a home with a large Trump banner attached to a flagpole, flapping loudly in the breeze. As Maria Cruz opened her front door, I heard the voice of a Fox News anchor coming from the living room, and I saw the glow of a television nearly as tall as I am. Nancy Pelosi appeared on the screen. “There’s that lady,” Cruz said. “She doesn’t think about the people. Es puro hate.” In the days after the 2020 vote, she told me, “I even cried every time I saw Trump. Because they stole the election from him . . . There’s no way that man could ever beat Trump. No tiene gente. He had to beg people to go see him.”

Cruz, sixty-two, is a teacher at a local high school where most of the parents and other staff members are Democrats. “They call me Mrs. Trump.” All her siblings are Democrats, but her views evolved. “I want someone that has the same values I do. That’s pro-life and all that. That actually wants to build up our nation, not ruin it.” There are conservative Latina voters like Cruz all across America. Every big, extended familia Latina has at least one. They helped propel the simpatico George W. Bush to victory. Twice. When the subject turns to Trump’s immigration policies, Cruz told me she feels little affection for Mexico. “I don’t even go there. The only thing they have good is the avocados . . . And I don’t like chili or cilantro either. I’m not missing anything.” Cruz told me that she watched Fox News religiously, and it had clearly given her an explanation for all that was wrong in her world. After hours and hours of its programming, she had come to internalize a dark, unflattering vision of Mexico.

metro atlanta

11% hispanic

biden 57%, trump 42%

About 70 percent of Latinos are of Mexican and Central American descent; they have immigration stories that pass, for the most part, through the West. But about 15 percent of Latinos are of Caribbean extraction, and their journeys have often taken them to the East. After leaving the Rio Grande Valley, I entered East Texas and Mississippi, passing through cities and rural areas rich with African-American history. I wandered around the Ninth Ward in New Orleans, which reminded me of the sultry towns along Guatemala’s Caribbean coast, where sea breezes flow through landscapes of tumbledown houses and palm trees. Finally, I reached the urban sprawl of Atlanta, stopping in a ranchlike suburb of curving roads and thin pine trees. A Mexican immigrant named Gustavo had recently purchased a home there, his own little piece of the South. (Gustavo also happened to be undocumented, which is why I’m using only his first name.)

Gustavo told me his friends had warned him that the subdivision would be filled with white people who hated Mexicans. But his new neighbors have given him a friendly Southern welcome. “I’ve accomplished a lot, considering the closed doors I had,” he told me in Spanish. In Mexico, Gustavo was unable to pursue an education past high school. He brought his family to Georgia twenty years ago, when it was an exotic new frontier for Latino immigrants.

I visited Georgia as a reporter around the same time Gustavo arrived there. New Latino communities were popping up then across the heartland; the barrios of Los Angeles and other cities in the Southwest had become crowded, and the meatpacking and manufacturing plants of the South and Midwest were beginning to hire large numbers of immigrant workers. In the early Aughts, I wrote about the founding of a Spanish-language radio station in Liberal, Kansas, and of a Spanish-language newspaper in Dalton, Georgia. I have a distinct memory of driving through Dalton and seeing a pickup truck rolling through the center of town with a large Mexican flag flying in the back.

When he arrived in Atlanta, Gustavo started by taking jobs in construction, despite knowing nothing about the craft. Now he operates a small remodeling business. We stood on the back deck of his new home, and looked out at the small patch of Georgia forest that belongs to him; the sense of personal achievement was palpable. He is a fit man in his fifties who works with his hands but has a deep hunger for intellectual conversation; and he is, as we say in Spanish, un hombre realizado. A man of achievement.

This is the time-honored trajectory of immigrant success, but Gustavo wakes up every day with the knowledge that a mere traffic stop could get him deported. When his father took ill, Gustavo couldn’t risk crossing the border to see him before he died. He hasn’t seen any relatives in Mexico since he left twenty years ago. “I believe in God, and I always place myself in his hands,” Gustavo said. “Whenever I leave my house, I don’t know what might happen. If one day my status counts against me, so be it. I can’t trust in men, or in politics.”

Republican and Democratic administrations have come and gone, Gustavo told me, yet his situation has remained the same. “When Obama was in office was when the deportations here were the worst,” he said. During the first three years of the Trump Administration, construction was booming, and so was Gustavo’s business—he was able to buy his home. Here as elsewhere on my journey, U.S. politics look different when seen from the perspective of working-class people. But Obama did create DACA, which allowed his eldest child to go to Harvard, and Gustavo is grateful for that. Gustavo’s two younger children, a nineteen-year-old son and eleven-year-old daughter, are both U.S. citizens. In November, Gustavo tells me with pride, his son went to vote.

little havana, miami

99% hispanic

trump 54%, biden 46%

I left Georgia and drove down the Florida turnpike, a lighted corridor of long straightaways that guided me into the foreboding darkness of a moonless night, cutting through the habitat of feral hogs, bobcats, and wild turkeys. Cuban Miami was waiting for me. When I reached Little Havana, I shed my fleece and felt beads of sweat dripping down my temples. The last time I was there, I’d reported on the case of Elián González, the five-year-old Cuban refugee who arrived in Florida in 1999 after an ill-fated ocean journey. Now I discovered that the block where he had lived during the monthslong custody battle that ensued had been renamed in honor of his drowned mother. This seemed like a good place to find a passionate Cubano, and in mere minutes I met one. Across the street from Elián’s old home, Santiago Faife snapped at me when I used the word “Hispano.” “No soy Hispano!” he said. “Soy Cubano!”

Faife is a tough seventy-one-year-old former bus driver who was wearing an NYPD baseball cap. As a young man, he’d been arrested in Cuba for “counterrevolutionary activity,” he told me. In 1980, Faife came to the United States. “I am a Republican since the first time I voted in this country, for Ronald Reagan,” he said. “I can’t betray the party, even if I didn’t like Trump at first.” Now he is a true convert. “Yo soy Trumpista,” Faife said, noting that he thought Trump should “declare martial law.”

A short walk from Elián’s old home, in the small parking lot outside the Va Cuba travel agency, I found a group of senior citizens who were more ambivalent. They recounted a Cuban melodrama of need, bitterness, and family separation. “Cuba has suffered sixty years of poverty, tragedy, disaster, shortages,” one woman told me. “Where Communism takes root, not even weeds grow.” The woman, her husband, and her sister-in-law were all in their seventies, graying and dressed in the frumpy casual wear of the struggling South Florida middle class. They were planning a visit to their family in Cuba, and the woman was afraid the government would retaliate if their names appeared in print. She hated the dictatorship. And yet . . . “If it hadn’t been for Fidel Castro, my children in Cuba wouldn’t have studied,” she said. All five of her kids were raised and educated under the Castro regime; three now lived in the United States, two in Cuba. “They did one good thing: they gave the people education. They taught the people to read and write.” Her children and grandchildren all became doctors and dentists—but those who remained in Cuba now rely on American relatives’ remittances to get by.

“Capitalism is hard,” the woman’s sister-in-law said. “You have to work, and sweat, and earn what you eat . . . But wherever they take freedom from you, no system works.” In Cuba, she had been employed by a university and had seen bright people cowed into silence. “Every time someone raises a voice, they cut his head off. They put him in prison and disappear him. They say he’s a ‘terrorist,’ a ‘delinquent,’ they shame him.” Her son avoided a prison sentence by fleeing during the Mariel boatlift, in which he and more than one hundred thousand other Cubans were allowed to leave the island. But the Cuban government repeatedly denied her an exit visa, as it did nearly every average citizen who applied for one. She didn’t see her son for twenty years, until she finally got an exit visa in 2000.

“Todo lo que he sufrido,” she said. All that I’ve suffered.

I thought of the story I’d just heard from Gustavo, who was also separated from his family for twenty years. “To be latinoamericano is to suffer,” I say.

“Seguro,” she said. Without a doubt.

“Sunday Morning in Spanish Harlem, 1986,” by Joseph Rodriguez © The artist

spanish harlem, new york city

57% hispanic

biden 88%, trump 10%

A blizzard was striking the Northeast just as I left South Florida, so I took my time, stopping for two days in Savannah, Georgia, where I met a Puerto Rican art student working at a local museum. At a gas station in rural North Carolina, I ate lunch in my car for the umpteenth time and heard the singsong of Mexican Spanish being spoken by a guy filling up at a pump. The temperature dropped as I journeyed north, but the New Jersey Turnpike was clear of snow, and finally I saw a strange apparition on the horizon—the New York City skyline. After more than one hundred hours of deserts, forests, farmland, and swamps, the steel bridges and glass towers of Gotham gleamed with a supernatural aura.

“Latino” remains a big-city appellation with a West Coast slant; in New York barrios, you’ll hear “Hispanic” just as often. When I crossed the George Washington Bridge and entered Manhattan, I found Spanish Harlem covered in snow. El Barrio is home now to a Latin American community composed of people with roots in the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Guatemala, and many other countries; for some, Latino best captures this ever-increasing diversity. Tony Rivera, a fair-skinned Puerto Rican, told me that he has come to embrace the term to describe himself and his neighbors. The importance of this pan-ethnic solidarity increased during the Obama and Trump eras. For Rivera, “the fact that Trump was so blatantly disrespectful to Puerto Rico and some other countries of color became personal for us. Obama was personal for us, because he was one of us.” Obama was a man of color with mixed-race heritage making his way in a white-dominated world, and his story resonated in El Barrio. “We have brothers and uncles that look just like him. We run the gamut with color. Whether you’re blanco, or caramelo, or prieto.” White, brown, or black.

But there are still many who are perplexed by the term. I met a diesel mechanic named Rolando Cortez on a snow-covered sidewalk. “Latinos? What are you fucking talking about?” Cortez asked. He is a short and stocky man, and a voracious reader, and he said he found it frustrating that the media lumps so many different kinds of people together into one category, implying they’re all the same. “Latino” means one thing in Spanish Harlem, Cortez said, and another thing in Queens, with its large Colombian and Ecuadorean communities. And then there’s the mixture of races in an average Puerto Rican family. Cortez told me that his grandfather had the blue-gray eyes of the Canary Islands but that he lived in Puerto Rico in a bohío, the traditional thatch-roofed hut of the Taino people. And his father had high Taino cheekbones and curly hair, “as a result of being mixed.”

I spoke to Cortez near White Playground, a park named after Walter Francis White, a civil-rights activist who was one of the early leaders of the NAACP. The bonds between Puerto Ricans and African Americans run especially deep in New York. Henry Comas, a sixty-two-year-old with Puerto Rican and Italian roots, told me that he grew up next door to a black family from South Carolina. “Our doors were always open,” he told me. “We ate in each other’s houses.” (Mexican kids in South Central L.A. grow up alongside black kids, too, and there is an emergent culture there that can be described as “Blaxican,” a term that originated in Los Angeles in the Eighties. My own godfather was an African-American neighbor of my Guatemalan parents in Hollywood.) Given this closeness, Puerto Rican voters in New York and elsewhere often see the world as black voters do. Among other things, they are more likely to support Democrats.

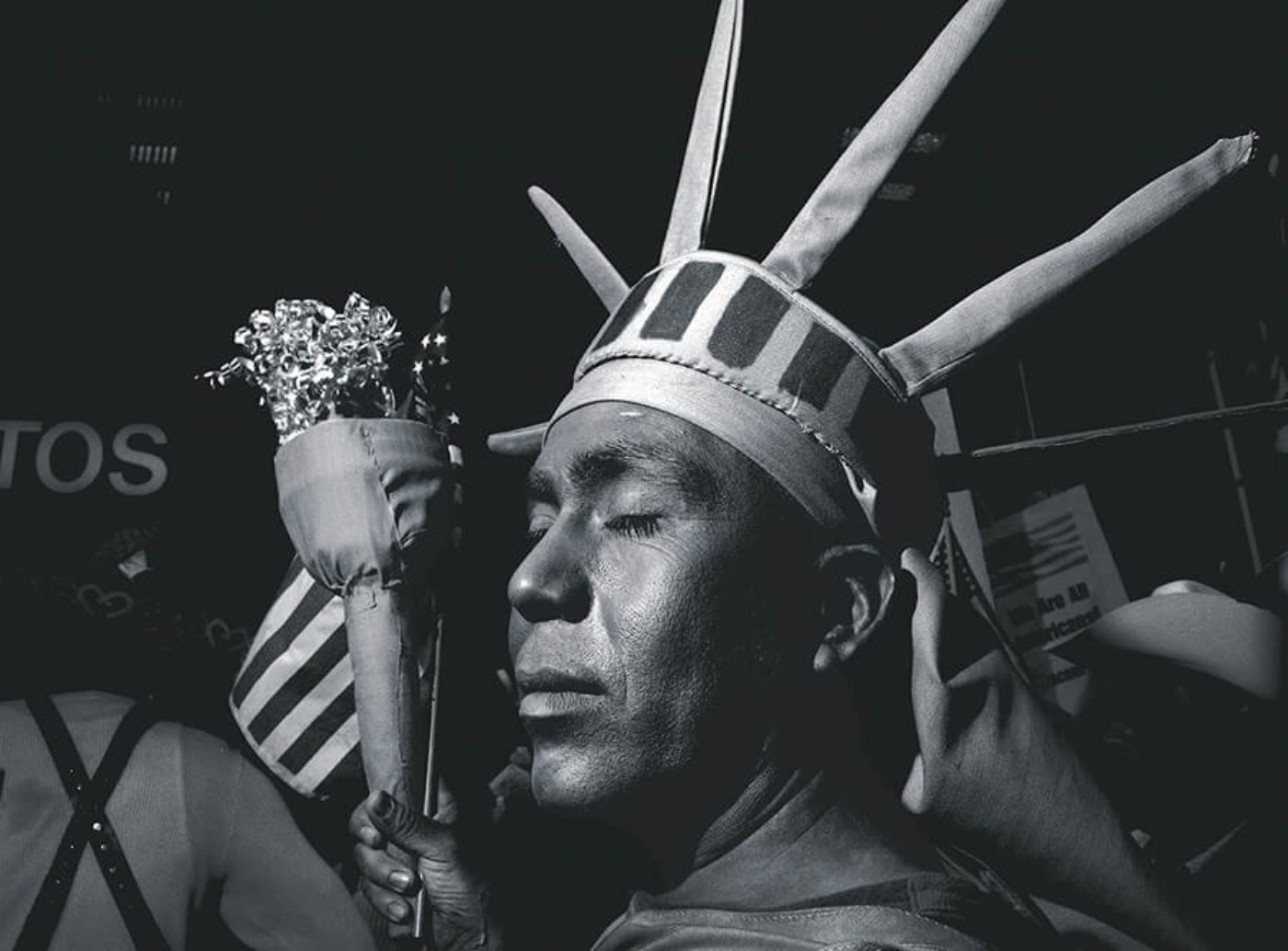

After more than six thousand miles on the road, I turned my car westward, toward home. I thought of the many Latino communities I had visited, and the people I had met, and the stories they had told me—about home and family, and the country we share. I could see that what binds Latinos together is that we have all been shaped by empire. We are brown, black, white, indigenous, European, and African; some of us speak Spanish and some of us don’t. But all of us have roots in the upheavals set in motion by American imperialism. Our ancestors have seen borders redrawn and fortified by the United States, and they have crossed those borders, by land, air, or sea, in the near or distant past. The love, the divisions, and the regrets in our families reach across those borders. Our ancestors have escaped marching armies, coups, secret torture rooms, and the outrages of rural police forces.

Like many other ethnic identities, Latino is a way of being that is grounded in suffering. To call yourself Latino is to resist assimilation, and to be conflicted about who you really are. All the major racial and ethnic identifiers in the United States have been created as foils to whiteness. What makes people of Mexican descent non-white is the fact that they can be exploited. The militarized border created an idea of Mexicans (and all Latin American people) as inferior and exploitable. As Latinos have become essential to the U.S. economy, the notion of immigrants as “aliens” has spread, and immigration restrictions have become more and more elaborate.

As I drove across the United States, I felt as though I were watching different parts of my story unfold. I saw my ambitious father, my cheeky mother, and my angry conservative relatives. No Latino person was a stranger, even if there was something exotic (to my California-born eyes) about the different places they lived in. I found a little bit of myself in all the climates and time zones I visited. In a strange way, the trip made me feel more American than ever.

But I was eager to see my family after four weeks on the road, so I was not going to stop in Chicago, or Grand Island, Nebraska, or the many other places where I could talk to Latinos. I could spend a lifetime traveling through the cities, towns, and fields where we work and live. During six more days of driving, I saw an unending stream of billboards for personal-injury attorneys, not to mention some Trump signs that were starting to fade. At a convenience store in the Mojave Desert, just 163 miles from Los Angeles, I waited in line behind a woman speaking Spanish. She was taking her time, and making sure her relatives got enough cream and sugar in their coffees. I rolled my eyes, and resisted the temptation to say, “Please, señora, can you hurry?” I was nearly home.