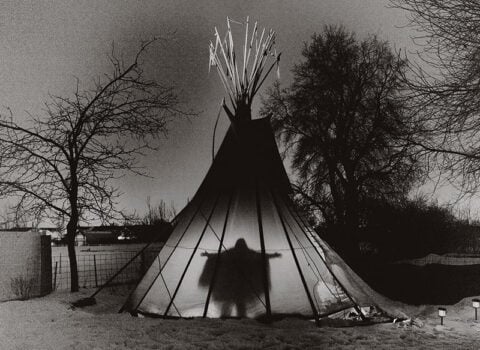

Photograph of Lissa Yellow Bird © Kristina Barker

I am alone in my apartment wondering what makes a good mother. Three days ago, on the eleventh of October, a packet arrived from a county social services department in North Dakota. The cover letter explained that a friend of mine was applying to be a foster parent. The department hoped I would answer some questions regarding “what you feel they can provide for a Foster Child.” The letter did not say so explicitly, but I understood it was asking me to determine what kind of mother my friend would make.

I use the word “friend,” though this is…