Notes on the State of Jefferson

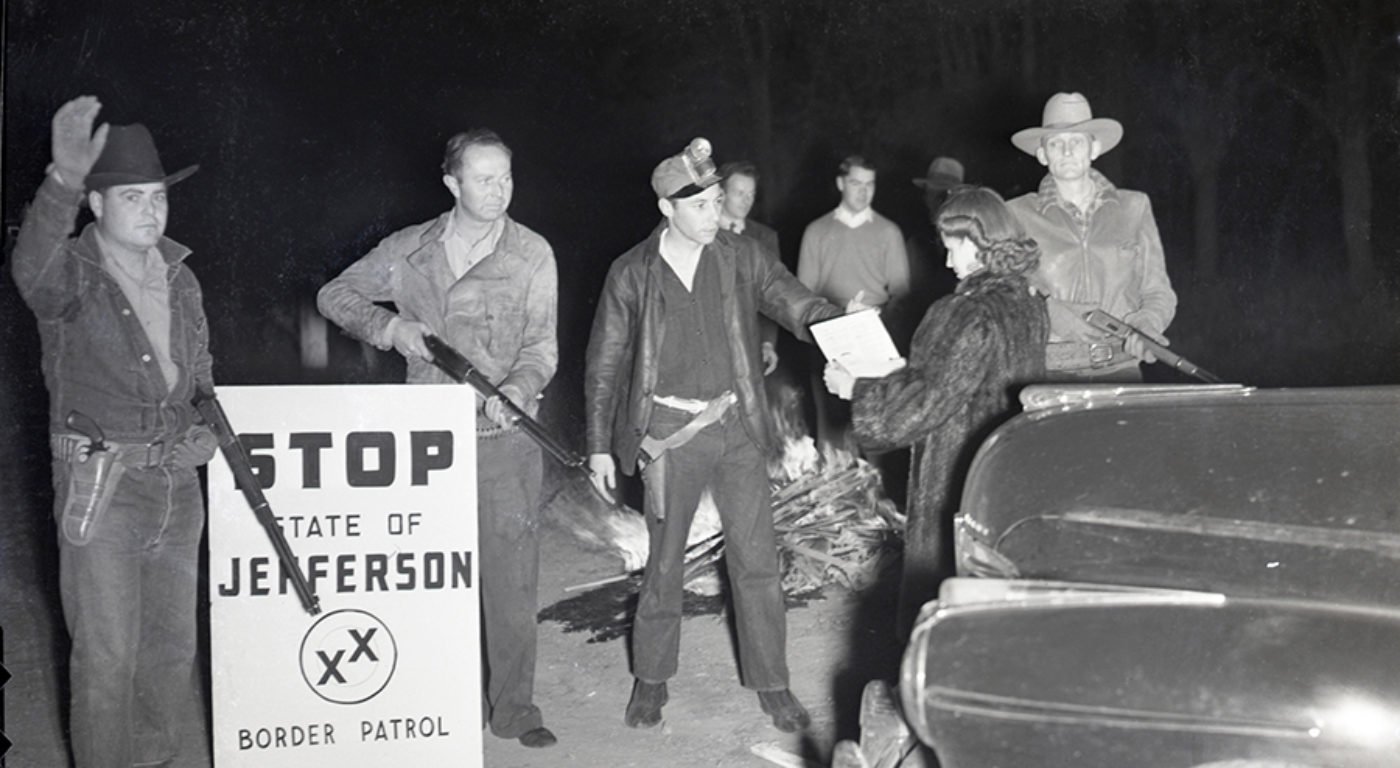

A roadblock outside Yreka, California © Rian Dundon

Notes on the State of Jefferson

Just after I arrived in Redding, California, a town of ninety thousand people at the north end of the Central Valley, some two hundred miles from San Francisco, a man approached my car and started pummeling my window with his fists. “Go back to the fucking Bay,” he bellowed. “We don’t want you up here!” I wasn’t surprised he had pegged me for an outsider—my truck was indisposed that day, and I had borrowed my girlfriend’s mother’s Tesla. But before I had a chance to explain that I did not, in fact, live in the Bay Area, an elderly woman walking a dachshund appeared on the sidewalk. The man seemed chastened. He backed up, and muttered to himself as he headed into a nearby government building, where a very extraordinary meeting of the Shasta County Board of Supervisors was about to take place. “This stuff is happening a lot, did you know that?” the woman said. “People in this county need to calm down.”

This was January 5, 2021. Two months earlier, a gun-store owner named Patrick Henry Jones had been elected to one of the five seats on the board of supervisors. He had campaigned on resistance to statewide pandemic protocols—his first act after being sworn in was to open in-person council meetings to the public—but his victory had tapped into other strains of local conflict. Among his most vocal supporters were a politically influential militia based in nearby Cottonwood, as well as advocates from a decades-old secessionist movement that aimed to carve out a “State of Jefferson” from parts of northern California and southern Oregon.

Jones and his allies saw themselves as freedom fighters taking control of a region that had long been neglected by distant metropolitan nodes of power, and they hoped to spur angry rural Americans across the country to do the same. As rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol the day after the board meeting, the State of Jefferson’s green-and-gold flag was one of many symbols of oppositional rural identity on display. “What we do will set the pace and tone for what the rest of the country will do,” said Carlos Zapata, one of the Cottonwood militia’s most prominent members. “Shasta County hasn’t been able to say that ever, about anything.”

As resistance to California’s COVID-19 orders grew, journalists began to take notice. Michael Lewis, of The Big Short fame, came to town, and the Los Angeles Times began publishing regular reports, calling Shasta County a “tinderbox,” torn between “government’s power and the degree that armed citizenry should take matters into their own hands.” As one headline in the Sacramento Bee put it: rural california is divided, armed for revolt. what’s the matter in the state of jefferson? But these reporters often struggled to explain what the State of Jefferson even was, let alone how the mythical state had inspired the apocalyptic reports coming out of Redding. So when Jones won his seat against a long-serving incumbent, I called his store. He suggested I come up to see his first board meeting.

Inside the hall, a large and rowdy crowd had assembled. The man who had approached my car—a local gadfly named Richard Gallardo, who once made the news for pushing to allow concealed firearms at his child’s elementary school—glowered at me from the wings. He was there as a “citizen journalist,” standing alongside a handful of reporters, the only attendees in masks. By the entrance, a few sheriff’s deputies chatted amiably with a group of young militia guys, including Zapata, who was shaking hands with supporters. Jones, with his buzz cut and boxy blue suit, looked on from his new board seat with serene impassivity while an unfortunate county employee struggled to set up a video call for those supervisors who had decided to attend remotely. “They didn’t have to deal with damn stuff like this when the colonists took down the English,” grumbled a man behind me.

The agenda was largely mundane, but when the floor was opened for public comment, things began to unravel. A long line of speakers took turns berating the board—for acting cowardly in the face of the pandemic; for betraying the region’s independent spirit by complying with state lockdowns and mandates; for allowing themselves to be made tools of oppressive state and national governments. Gallardo strode down the center aisle, flexed his muscles, and shouted, “I’m. So. Angry,” before storming out. Others were more composed. “Flee now, while you can,” one man said, staring coldly at the supervisors. “The legitimacy of this government is waning. . . . When the ballot box is gone, there is only the cartridge box. You have made bullets expensive. But luckily for you, ropes are reusable.”

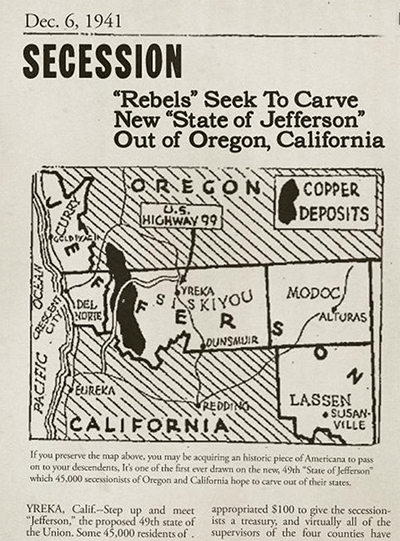

The State of Jefferson was probably named for Thomas Jefferson. But the name may also have been a winking homage to Jefferson Davis. No one is really sure. The idea as we know it today was ginned up in the Forties by Gilbert Gable, the legendarily alcoholic mayor of Port Orford, Oregon, with the help of Stanton Delaplane, the self-promoting San Francisco Chronicle reporter best remembered for his investigation of a philandering cable-car conductor whom he dubbed “The Ding-Dong Daddy of the D Car Line,” as well as for introducing Irish coffee to America. A former publicity man, Gable was bothered by the rutted, washed-out dirt roads of the California-Oregon borderlands, which he saw as a bitter symbol of government neglect. His calls for infrastructure development gave birth to a unifying cross-border ideology: that this rural expanse populated by miners, ranchers, and loggers had been mistreated and misunderstood by a government run by urbanites, whose way of life depended on the resources the region produced, but who regarded the people who actually produced them as backward and alien.

Gable persuaded a county court to appoint him to a commission investigating the possibility of secession. The idea caught fire. Supporters drafted a declaration of independence and designed a seal: two black Xs, symbolizing the way the region had been double-crossed by Salem and Sacramento, set over a yellow circle, representing a gold pan. One night in 1941, Delaplane and Gable drank a bottle of 150-proof rum in an Oregon cabin and planned a major publicity push, but Gable died of a heart attack the next day, possibly caused by the drinking. (The local paper said it came from “nervous fatigue, the result of his indefatigable efforts to bring development” to the area.) Undeterred, Gable’s allies found a retired judge named John Childs and appointed him “governor.” He organized a protest to demand better roads.

On the day of the demonstration, hundreds of Californians, accompanied by drum majorettes and a mounted sheriff’s posse, paraded down Miner Street in Yreka, a town in the far north of the state. With helpful stage directions from newsreel cameramen, men on horseback rode defiantly around a sign marking the Oregon border, and replaced it with one announcing allegiance to Jefferson. Childs gave a speech and was met with wild applause. “The State of Jefferson is the natural division geographically, topographically, and emotionally,” he said. “In many ways it is a world unto itself.” Delaplane seems to have talked some armed men into setting up roadblocks outside town, some of whom stopped a state trooper and told him to “get back down the road to California.” Six months later, for his reporting on the revolt that he himself fashioned, Delaplane was awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

A news clipping from 1941

The original carnival of rebellion ended when the United States entered World War II. But the secessionist dream lingered and eventually settled in the minds of subsequent generations, even those who never thought that the state could become a political reality. In 2013, Mark Baird, a rancher and former sheriff’s deputy in Siskiyou County, relaunched the movement for Jefferson statehood. His primary concern was a lack of representation in higher levels of government. He often cited a forestry policy that prevented most of northern California’s federally managed forests from being logged, which had more or less wiped out the region’s economic base. Former loggers and mill operators were cast by government officials as destructive and backward, clinging to a misbegotten resource economy instead of shifting to one based on tourism. Statehood, Baird thought, would give the region a voice at the federal level, and keep it from being reduced to an impoverished colony of California’s rich, liberal population centers.

Baird set about persuading individual county governments to issue proclamations in support of secession. In September 2013, Siskiyou County became the first to pass a State of Jefferson resolution. Modoc County, in the remote northeastern corner of the state, followed a few weeks later. Soon, people throughout northern California began demanding that their county governments sign on. When the board of supervisors in Shasta County refused, organizers collected fifty-eight thousand signatures and told the board that they would be moving forward without them.

Today, almost every county north of Sacramento has passed a resolution in favor of joining the State of Jefferson. From Mendocino to Alturas, neon Xs glow in bar windows and billboards exhort passersby to join: jefferson, the 51st state. The Jefferson project is sometimes invoked as a gentle nod to regional solidarity—the local NPR network is called Jefferson Public Radio—but it has increasingly come to signify a defiantly conservative strain of politics. To others, Jefferson represents something more insidious: a barely concealed desire to carve an ethnostate out of the only part of California where whites still constitute a majority. The State of Jefferson, in that sense, maps neatly onto our national political divide.

A few days after the board meeting, I went to meet Jones at his shop. Business was clearly booming. The rifle racks were half empty, and the clerks seemed harried as they hustled about, commiserating with customers about lengthy delays and other annoyances that came with purchasing firearms in California. Jones, who has the reddish face of someone who spends a lot of time outdoors, leaned across a plexiglass case filled with pistols. “It seemed like we had been electing people that weren’t from here,” he said when I asked why he decided to run for office. “They were mainly Bay Area transplants, people from Fresno, places like that. And we don’t mind them, we just don’t want to change to what their idea of the world is. We like who we are.” He frequently referred to the “values” of the region—faith, family, patriotism— which he said were under attack both by bureaucrats in Sacramento and newcomers from the Bay. He sincerely believed that secession was the best way to preserve those values, even if it was unlikely to happen anytime soon. “If I could only do one thing it would be to split the state,” he told me. “It would be the finest thing I could ever accomplish.”

Jones’s path to the board of supervisors began with a haircut. On May 1, 2020, Les Baugh, a soft-spoken county supervisor, posted a photo of himself during lockdown getting a trim from Woody Clendenen, the leader of the militia in Cottonwood. This regiment, the power center of a network of militias that extended from the Central Valley to the Oregon border, had formed in 2010, and had since grown into a major social and political force. Militia members more or less officially policed the streets in Cottonwood, a hot, flat, and slightly disheveled town on the county line. Official law enforcement presence was almost nonexistent. Candidates for local office regularly attended militia events looking for support, and Clendenen quietly emerged as a major power broker. “It grew into almost kind of a political action committee,” he told the Los Angeles Times. The photo of Baugh left many moderates and a few board members distraught, as they correctly predicted it would go viral as a symbol of anti-lockdown sentiment.

A group of mothers frustrated with school and business closures and churches critical of California’s COVID-19 policies soon formed a group called the Open Shasta Coalition, which allied itself with militia members and Jefferson secessionists. Meetings of the board of supervisors became scenes of swelling chaos, as crowds tried to storm closed sessions and demand the board pull out of state pandemic protocols. The local sheriff, bowing to the county’s new political reality, allowed the annual Cottonwood Rodeo to proceed, at a time when large public events were being canceled across the country. But the clearest sign of the movement’s growing power was a speech by Zapata at one of the board meetings. Video footage shows Zapata standing at a lectern. He is wearing his usual uniform of a baseball cap and tight T-shirt, and his thick arms are crossed, as if uncomfortable with what he is about to say. But he remains poised and calm throughout his address. “Right now we’re being peaceful,” he says. “But it’s not gonna be peaceful much longer.” He points at the crowd. “I’m probably the only person that has the balls to say what I’m saying right now. That we’re building, we’re organizing.” He talks about friends from the military who had killed themselves amid the isolation of the pandemic. “I’ve been in combat, and I never want to go back again,” he says. “But I will, to save this country. If it has to be against our own citizens, it will happen.”

The video raced through Facebook—by far the dominant source of local news in the rural West—and was quickly picked up by right-wing media outlets. Zapata gained tens of thousands of followers. He became a regular guest on Alex Jones’s radio show, where he predicted “blood in the streets.” Zapata’s speech gave the Shasta County protests a national audience, and the board meetings remained a site of mayhem until they moved online in November 2020.

“Sheep sign” (detail), a Polaroid by Preston Gannaway from the series Today I Will Be © The artist

Shortly after the speech, Patrick Henry Jones announced his candidacy for a board seat. He promised to reopen the county, which made him an anti-tyranny crusader to some and a sinister antigovernment extremist to others. With the help of a $100,000 donation (the largest given to a local candidate in California history) from Reverge Anselmo—the son of a Univision co-founder who had left Shasta County years earlier because of a building permit dispute—Jones won the seat with 54 percent of the vote.

I asked Jones whether he thought things would calm down after the pandemic, or if something larger had snapped. “This is going back to the 1850s,” he said. “You have this tension, those two different groups.” I assumed he was talking specifically about California, and the regional differences that helped build the Jefferson movement. But he was referring to a national gulf between the centers of globalized cosmopolitanism and the rest of the country. “The people in the rural areas—we’re different from the city areas. Because we want our freedoms and they want more controls,” he said. “You know, if I were living back in the 1850s, I’d think that this was probably what led up to the Civil War.”

I was still a bit hazy about what Jones wanted to accomplish in office. Everyone seemed to be talking about issues far bigger than anything that could get sorted out by a county board. And he didn’t have a majority to support his plan to pull out of the state’s COVID protocols. I asked whether he was involved in the movement to recall the governor, Gavin Newsom, which was then gaining momentum. Jones gave me a mischievous look and leaned over the counter. “You might want to check back on that here soon,” he said. “We haven’t announced it yet, but there’s going to be a recall here too.” I found the idea hard to take seriously—a sitting board member leading a recall against his fellow members in a fight that was more a clash of values than policy—but Jones looked serious. “Check back,” he said. “It’s going to get interesting.”

The next day, I dropped by Woody Clendenen’s barbershop for a haircut. I had been having trouble contacting some of the key figures in the crusade to take over the county—Terry Rapoza, one of the Jefferson movement’s highest-profile leaders, had flatly declined to meet with me, and I couldn’t get Zapata to return my calls—so I figured I’d just show up as a paying customer. “You must be the one Terry told me about,” Clendenen said as I walked in. “I’d been thinking you might come by.” He was a graying, fit fifty-five-year-old, wearing a polo shirt over a slight paunch and chatting jovially with a row of customers. I asked how he knew who I was. “You don’t look like you’re from Cottonwood,” he said. A chorus of guffaws rose up. “You don’t smell like horseshit,” someone called out.

The shop was packed, its walls covered in the trappings of defiant rural patriotism: Jefferson flags, framed photos of young men in uniform, Confederate insignia, flyers advertising horse trailers for sale. Clendenen exuded an air of avuncular authority. He was a barber in the way that Tony Soprano was the owner of Satriale’s Pork Store. As he cut hair, he was constantly interrupted by calls from Zapata or Jones, and by people wandering in to ask favors or talk militia business. Just after I sat down, a hefty trucker in a black hoodie walked in. “Well, the FBI just came by,” he announced. Clendenen invited him to go on. “I just told them that I am a legally armed American in my home, I’m happy to talk to them, but they can’t come in the house. They weren’t too bad or nothing.” Clendenen barely looked up from the haircut he was giving to a boy who looked to be about eight years old. “You did good,” he said.

I sat around for at least an hour before it was my turn. Clendenen was surprised to learn that we had some acquaintances in common from my years reporting in the more rebellious corners of the West. He brought up Ammon Bundy, the antigovernment icon who was then running for governor of Idaho, whom he clearly considered a bit of a hero. I mentioned that I’d been embedded with Bundy through most of the 2016 standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, and Clendenen perked up. It turned out that Dwight Hammond, the Oregon rancher whose five-year prison sentence for arson had instigated the standoff, had stopped by the barbershop in 2018, shortly after a pardon from Trump led to his release. “If you know the Bundys, I think Carlos is going to want to talk to you,” Clendenen said. “You guys might have a lot to talk about.”

Forty-five minutes later, I was sitting in the Palomino Room, Zapata’s restaurant. It was sparsely furnished, and looked like it could still use some breaking-in after a recent renovation. Zapata found me at the bar, and turned out to be more interested in the fact that we both practiced Brazilian jiu-jitsu than he was in the Bundys. He handed me a beer and took me to a back room where we could smoke.

I admit I liked him immediately. Most people do at first, even those who regard him as a malign thug. He is square-jawed, with a wrestler’s frame and a deep, raspy voice that lends him an obvious charisma. “I’m a pretty complex dude,” he told me. “The more I drink and the more we talk, the more you’ll get to know the intricacies of my mind. And my mind is a weird place.”

Zapata grew up in California’s wine country, the son of Peruvian immigrants. He told me a sweeping, hard-to-confirm narrative about his family’s arrival in the United States: his grandfather, he said, had been Salvador Allende’s cousin, and had owned a grand house with eleven maids before being imprisoned by the Peruvian government. When he died, he left Zapata’s grandmother with nothing. She came to the Bay Area and cleaned houses. “We have a rich history of revolting in our family,” he said. “It’s strange because they were socialists, but if you think about it they were only socialists because they were revolting against a military government, right? I don’t know. It’s fucking crazy.”

At seventeen, Zapata enlisted in the Marines and moved to Redding to attend a small Christian college while still in boot camp. He spent six years on active duty, including a stint in Iraq, then seven years in the reserves, eventually achieving the rank of major. He got his black belt in jiu-jitsu, opened a gym, and started a business raising rodeo bulls.

Then the pandemic hit, and he became a rebel. His awakening was a faster, harder-edged version of one that more than a few people—who, like Zapata, had voted for Barack Obama and considered themselves politically moderate—experienced in the months to follow. It started with the angry sense that masks and lockdowns were forms of unaccountable government overreach, and evolved into the sense that liberal speech-policing and the new power of Big Tech over daily life were signals of an impending dystopia. He began to think, as many in northern California did, that liberals were conspiring to build a nation of docile people who lived in condos and communicated via Zoom, too scared to challenge the dictates of experts or government officials. “Believe it or not, I’m not this right-wing nut,” he said. “If you and I were sitting here a year ago and you’d asked if I would join the militia, I’d be like, ‘Fuck no, dude. Those are a bunch of paranoid tinfoil sons of bitches.’ ”

But he had become convinced it was time to “take a hard stand.” He asked around about the militia and was directed to Clendenen. “I was like, ‘Woody is the head of the militia?’ ” he said. “The guy with the barbershop? Dad?” Clendenen saw Zapata’s potential as a leader, and set about immersing him in the politics of the Western hard right.

Shasta County’s conflict with California was part of a worldwide struggle, one in which local identity was under assault as much from Davos as it was from Berkeley. “Even just waving the American flag now,” he said, “they want you to think that’s racist, that you’re a white supremacist. Every country has done some bad things. How the fuck is patriotism a bad thing now?” His media appearances after his speech had marked him as somebody willing to say what others were not: that resistance to lockdowns was only the beginning of what would likely be a bloody resistance to everything liberal America represents.

We went back to the bar, where we were interrupted by a waitress who said there was a woman on the phone offering ammunition to the cause. “Save her number,” he said. “If she’s got ammo, fuck, I’m going to call her.” “She’s been very persistent,” said the waitress.

Zapata was getting a lot of calls from strangers. “I became kind of the de facto face of the movement,” he told me. He was convinced that he had been conscripted into a world-historical struggle, and that the times called for men like him who were willing to risk it all. “Guys who were in the Marines with me tell me sometimes, ‘You know, like there’s something about you. You were the guy,’ ” he told me. “And I’ll admit it, I am a violent motherfucker, dude. Some people can probably attest to that.”

A few weeks later, I showed up at the cheery little house of a sixty-five-year-old woman named Doni Chamberlain. She had been chronicling Shasta County politics on her website A News Cafe for fifteen years, and had recently started to get national attention for her reporting. She showed me into her living room, which doubled as her office, then served me iced tea and homemade coffee cake, which she later insisted on boxing up for me to take home.

As Jones had hinted to me, a campaign had been organized to recall the three board members who hadn’t voted to defy Sacramento’s pandemic restrictions. Both supporters and opponents of the recall described this to me as a battle for the “soul of the county.” Threats were circulating on Facebook, and many liberals opposed to the recall, including Chamberlain, feared that the vitriol would soon turn violent. She had started peering into her mailbox to make sure no one had left a rattlesnake. “I actually asked my sister if that was a normal thing to do,” she told me. “She was like, no, it’s not.”

In 2020, Chamberlain had published a lengthy open letter to Newsom in which she more or less dared the governor to crack down on the sheriff, Baugh, and the militia for flouting pandemic regulations. “What good are executive orders during a pandemic if law enforcement leaders refuse to enforce COVID-19 rules put in place to keep us safe?” she wrote. She developed an obsessive focus on Zapata in particular, though she refused to speak to him. “Don’t wrestle with a pig,” she explained to the Los Angeles Times. “You just get muddy. And the pig likes it.” She published detailed investigations on seemingly minute questions, like whether Zapata had, as he claimed, flown to Tampa during the pandemic without putting on a mask, and whether he secretly owned a strip club in the city, issues that were treated in her pages as epochal scandals. She promoted a Facebook group in which people reported businesses that appeared to be violating shutdown orders, which came to be seen as evidence of a wider epidemic of snitching.

Zapata, in turn, set about tracking down his online antagonists, in one case threatening to destroy the trailer of a man who had insulted him on Facebook. “I want to address these people that think that it’s a good thing to do to go around ratting your neighbors, and your businesses, and your local towns off,” Clendenen said in a December Facebook Live stream. “If you rat somebody off . . . we just don’t need you in our community. I don’t even want you here. So go move off down to San Francisco or somewhere where your kind live.”

Chamberlain, who grew up in Shasta County, seemed genuinely shocked by how suddenly these political divides had surfaced. “You know, when I grew up in the Sixties and Seventies, it was mainly Democratic,” she said. “A union town, mill town, you know, with lumber mills, lots of blue-collar work. And then over the years as the mills closed, it shifted.” Meanwhile, a steady stream of transplants from Sacramento and Los Angeles moved up during the Nineties, driven by the costs and crowds of urban life, resentful of crime and immigration, and often drawn by an idealized vision of the Jeffersonian lifestyle. But the pandemic set off a new wave of rapid migration to the area, attracting new residents who viewed the rugged individualism of the Jefferson separatists as an antiquated fantasy. Many of those in county government agreed, leading conservatives to believe that no level of government—from the board of supervisors to Sacramento to the White House—could legitimately represent their values or interests. This was the real significance of Jones’s election: he hadn’t been elected to govern so much as be the first step in refashioning a government that many no longer believed in. No one, not even Jones’s supporters, seemed to have a clear answer as to whether this would—or could—happen through democratic means. “His only purpose is to not be under the tyranny of government,” Chamberlain said. “If Patrick Henry Jones could get a seat on the board, it’s almost like pirates, you know? One gets on and then they throw the rope and they let the others on.”

Last December, realizing that I rather enjoyed the State of Jefferson lifestyle myself, I moved up to Shasta County full-time, renting a place in a tiny canyon hamlet about an hour north of Redding. Patrick Henry Jones was now my county supervisor. The recall organizers had struggled to gather signatures. In addition to disorganization, they had to contend with evacuations caused by wildfires, including the Dixie Fire, one of the largest in California’s history. But with the help of $450,000 in political contributions from Anselmo—the same donor who helped Jones get elected—they managed to successfully force an election in the district held by Leonard Moty, a former Redding police chief. All the viable candidates running to replace Moty were sympathetic to Jones, which meant that if Moty were voted out, the secessionists would command a majority. They could very plausibly claim to have taken control of the county.

Recall supporters planned to flood the last meeting before the February 1 election, in a show of force they were calling Operation Last Supper. But the volume of death threats being sent to supervisors prompted the county to move the meeting online. Jones, whose key card to the county administrative building had been disabled, set up a large television and sound system outside. When I arrived, he was looking dapper in a black overcoat and white dress shirt, standing before a crowd of around one hundred people and a handful of sheriff’s deputies. Doni Chamberlain stood only a few feet away, filming the proceedings.

At the back of the crowd, I spotted Elissa McEuen, a Bay Area transplant who had done much of the organizing work behind the recall. She’d moved to the region only six years earlier, and, like Zapata, had experienced a political awakening when the pandemic hit. She was frustrated by the way that Moty and his supporters had portrayed themselves as fighting an effort led “by extremists, by insurrectionists,” she said. “The driving force behind the recall was mothers.”

But to Chamberlain and the county’s liberals, the recall was very much about the militia, their guns, and the tacit support they seemed to enjoy from local law enforcement. Zapata often acted as if he was untouchable—several months prior he had been acquitted of a battery charge after accosting a comedian who had mocked him online. Recall opponents tried to paint Jones and his allies as a bunch of fringe extremists, but they seemed to miss the fact that what they called extremism appeared to constitute majority opinion in Shasta County.

On Election Day, a helicopter flew over Redding, trailing a banner reading shasta, as a trickle of voters filed into the county elections office. Moty, apparently concerned for his safety, decided not to have an election-night rally. But I heard a rumor about a pro-recall party at a weight-lifting gym near Zapata’s ranch, in Palo Cedro. When I arrived, Jones was watching the returns with Clendenen, who said a friendly hello and encouraged me to take advantage of the open bar. Everyone seemed nervy, and the early returns showed the recall attempt failing by a narrow margin. Zapata was in a pensive mood. “We knew this was going to be tough,” he said. “We gave it absolutely everything.” But he grinned when I told him I’d moved up there. “That’s the thing, man,” he said. “Once you get a taste of this lifestyle, you just can’t let it go.”

When I drove into town the next day, the winds had shifted. The pro-recall contingent was winning by five percentage points. Moty put out a terse statement, thanking volunteers and saying he had been proud to stand against the “anarchists, extremists, and white supremacists wanting to take over our county.” It still wasn’t clear who had won the seat, but it didn’t really matter. Jones declared victory. Shasta County had a new political order.

The state’s major papers reacted with predictable alarm. could populist, militia-backed shasta county recall effort provide roadmap for other races? the Mercury News wondered. extremists are set to take over this california county: will more of the state be next? asked the Los Angeles Times, noting that the recall proved that elections could go “very wrong, even in liberal California,” and worrying that insurrection might sweep across the rest of the state’s restive hinterlands—just as Zapata hoped it would.

There’s no doubt that Shasta County will serve as a model for other rural counties. Already, advocates in California’s Nevada County are hailing Zapata and Clendenen as inspirations. But the recall did not go wrong. It went the way that 56 percent of the voters in District 2 of Shasta County—who were not bothered by the idea of voting alongside militiamen, or by the thought of electing a government that reporters from California’s metropoles regarded as extreme—thought it should go. “I’m not calling for violence,” Zapata told me when we first met. “We’re ready to do violence to protect ourselves.” He often talked about the recall as a last stand before civil war. But his side had won. So for now, they would have to get down to the business of trying to govern, in a state that was still only a dream.