The Fight to Choose

“Savita Halappanavar,” by Laia Abril, from On Abortion, which was published by Dewi Lewis, and is the first part of her project A History of Misogyny © The artist

Until the late twentieth century, Ireland was effectively a social theocracy. The Catholic Church imposed rigid controls on many aspects of life, particularly women’s sex lives, going so far as confiscating the babies of unwed mothers and selling them for adoption abroad. Abortion was banned. In 1983, a two-thirds majority voted to enshrine the ban in the country’s constitution, in the form of an amendment declaring “the right to life of the unborn . . . equal [to the] right to life of the mother.” Decades of acrimonious debate followed, while every year thousands of Irish women made the journey to Britain, where abortion has been legal since 1968. Meanwhile, doctors were deterred from performing abortions even when the mother’s life was in danger, leading to cases such as that of Savita Halappanavar. In October 2012, a hospital refused to abort her pregnancy even though doctors acknowledged that a miscarriage was inevitable. Within a week she had died of sepsis.

Halappanavar’s death provoked a huge outcry, and in 2018 the Irish government authorized another referendum on the amendment. Despite heavy lobbying by the opposition, the Irish people voted to repeal the amendment by almost exactly the same percentage as had endorsed it forty years before. Following the repeal, the Irish parliament made abortion legal, at least through the first twelve weeks of pregnancy, and longer when medically necessary. The debate surrounding the amendment attracted keen attention abroad, including from the United States. “We did have activists coming from the States and saying, ‘Why don’t you do this, that, and the other? That’s what we do,’ ” recalled Ailbhe Smyth, a leader of the repeal campaign. “And I remember saying to one poor, hapless woman, ‘Really, you’re not doing so well yourselves over there.’ ”

“The Right to Choose,” by Laia Abril and Carmen Winant © The artists

In the United States, abortion rights have been in retreat almost since the day Roe v. Wade was decided, fifty years ago, and the leak on May 2 of Justice Samuel Alito’s draft opinion overturning Roe foretold a further rout. The next day, voters in western Michigan went to the polls in a special election to fill the seat for state House District 74, which for decades had been firmly in Republican hands. This time was different, however, with the Democratic candidate, Carol Glanville, crushing her Republican opponent by eleven points. Meanwhile, voters in Leelanau, a county to the north, on Lake Michigan, threw out a Republican legislator and gave Democrats control of the county government for the first time.

I heard the news from Betsy Coffia, a forty-four-year-old newspaper editor and social worker who is running against a far-right Republican—“an extremist against choice”—for a seat in the state legislature this November. “Just think about the timing,” she said. “We all had just gotten the news on the Monday night before the special elections, and you had a bunch of really angry women who woke up the next morning seeing red and ready to do something about it.” The Democrat who won the county commissioner race, she pointed out, had lost twice before to her right-wing opponent. “She beat him this time!” Other issues played a role—the county election was a recall provoked by the Republican’s opposition to funding for early-childhood services—but Coffia was sure that these upsets were due to the leak. She could see the effect on her own campaign. “I’ve been knocking doors for about a month now,” she told me in early May. “The minute that Roe leak happened, suddenly it was an issue that folks were bringing up, saying ‘Oh my God, they’re really going to do it,’ ” she said. “It went from theoretical—this bogeyman that might overturn Roe someday—to now that sense of horror that it not only might be, but it is happening.”

The abortion debate has always been a central feature in Coffia’s political life. She grew up in a deeply religious, rural, working-class family. “We were not allowed to celebrate Halloween because it was the devil’s holiday,” she told me. Her father was a Baptist preacher and her mother cleaned houses. “We were taught in my church that you should always vote in every election, and the only things you needed to know about candidates were: are they anti-abortion and are they anti–gay rights.” She recalls the tight organization and messaging discipline of the church-based anti-abortion movement. Even as a preteen she was discussing how to create a Supreme Court that would overturn Roe. “This has been a forty-year strategy that I was literally a foot soldier for as a child,” she said. “So this world my opponent has been voting for and supports, I lived it: no body autonomy, no privacy, no choice.”

Coffia is fortunate that Michigan, long and egregiously gerrymandered, has now followed the guidance of an independent redistricting commission, adding to her district a county that went for Biden in 2020. (The districts that flipped blue on May 3 still had their old boundaries.) Wisconsin was also redistricted after the 2020 census, with a rather different result. “Wisconsin has been one of the most gerrymandered states in the country for the last ten years,” Greta Neubauer, the leader of the Democratic minority in the state assembly, told me. “The maps that were just adopted are worse.” Biden won the state in 2020 by twenty thousand votes; under the new maps, she pointed out, the same result would give Democrats a mere third of the seats in the assembly: “The will of the people is not represented in the makeup of the legislature.”

Like Michigan and eighteen other states, Wisconsin has a law in place (dating to 1849) that would ban abortion the moment Roe is struck down, and there would be nothing that the state’s Democratic governor, Tony Evers, could do about it. “Only eleven or twelve percent of Wisconsinites support a full abortion ban,” Neubauer said. “But that is essentially what we will have if Roe is overturned.” Republicans were not making any noticeable effort to change that, she said—surely an understatement, given that the leading Republican candidate for governor, Rebecca Kleefisch, has endorsed the notion that a rape victim should turn a “lemon situation into lemonade” by having the rapist’s baby.

Like Coffia, Neubauer has seen firsthand the energy and outrage generated by Alito’s opinion. While recruiting candidates for the fall elections, she has found that conversations have “absolutely been different since the Roe leak, particularly with female candidates who just feel that this is a moment in which they need to step up.” At a rally in her district the weekend after the leak, she talked about her grandmother’s work on reproductive rights in the Sixties and Seventies, which provoked sustained harassment, including bomb threats. A succession of women approached her to recount their own pre-Roe abortion stories, such as that of an eleven-year-old victim of incest. “That’s the experience that I think is informing so many of us who, frankly, did not think that we would be in this moment and be facing this reality,” she concluded.

For the national Democratic Party, the news that the Supreme Court was about to kill Roe was an obvious opportunity to galvanize liberal voters. Amid mounting inflation, the failure to enact promised reforms, disaffection over crime rates, and other propellants of party despondency, Alito’s unsparing opinion offered a ray of hope. Polls, after all, confirm that a majority of Americans favor legal abortion and reject the draconian edicts spewing out of Republican-controlled state legislatures that already render abortion out of reach for millions of women. Nancy Pelosi told Democratic House members that “Republicans have made clear that their goal will be to seek to criminalize abortion nationwide,” while Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer quickly brought to the floor a bill to protect abortion access. As Jim Duffy, a seasoned Democratic consultant, remarked to me: “They’ll raise a boatload of money out of this.” Sure enough, a message from the strategist James Carville soon popped into my inbox stating that news of the impending court decision had made him “so damn angry I can hardly type this message to you, Andrew,” and that if “MAGA extremists” took the Senate “you can kiss the right to privacy good-bye!” The Democratic fundraising outfit ActBlue reported a $12 million haul in the day following the leak. Despite the prospective harvest, everyone knew that efforts to legislate Roe as the law of the land were doomed, as the Senate defeat of the Women’s Health Protection Act demonstrated. Republicans did not need the filibuster to defeat the bill, as the “moderate” Democratic Senator Joe Manchin joined them to deny it even a simple majority. The administration had non-legislative options, such as deploying the FDA to expand access to abortion pills, but officials displayed little interest in concrete measures, preferring to use abortion as an election talking point.

Such inaction was in keeping with Democrats’ record in the fifty years since Roe: appeals for votes and cash premised on the threat posed by an antichoice Supreme Court, coupled with a refusal to codify Roe when they controlled both Congress and the White House. Campaigning in 2007, Barack Obama pledged to Planned Parenthood that “the first thing I’d do as president” would be to sign the Freedom of Choice Act, which would eliminate all federal, state, and local restrictions on abortion. Once in office, he announced that this was “not my highest legislative priority,” adding that while he believed that women should have the right to choose, it was more important to “tamp down some of the anger surrounding this issue [and] focus on those areas that we can agree on.” The bill languished in committee until consigned to oblivion by the Tea Party insurgents who swept the polls in 2010, displaying no intention of tamping down anger on this or any other issue.

That year, Obama signed an executive order stipulating that no federal funds stemming from the Affordable Care Act could be used to enable abortions. A dozen smiling antiabortion Democratic legislators attended the signing ceremony (press were excluded). They had demanded the measure as their price for supporting the president’s cherished health care legislation. Among them was Henry Cuellar, representing a mostly Latino district in south Texas, who a decade on is the only professedly anti-abortion Democrat in the House. As such he faced a strong primary challenge this year from Jessica Cisneros, a progressive immigration attorney, in which she forced a runoff. Her campaign highlighted Cuellar’s lone “no” vote among House Democrats on the Women’s Health Protection Act. “With the House majority on the line, [Cuellar] could very much be the deciding vote on the future of our reproductive rights and we cannot afford to take that risk,” she declared days after the leak. The party leadership echoed Cisneros’s rhetoric, but their actions sent a different message. Congressman Jim Clyburn of South Carolina, one of the triumvirate presiding over Democrats in the House, campaigned with Cuellar (who also has a staunch progun and anti-union voting record), calling the party a “big tent.” Pelosi spoke eloquently on television of the need to pass abortion rights into law, even while urging Texans to support him. PACs close to the party leadership, along with corporate and pro-Israel groups, poured millions into his campaign. “South Texas is Democratic, but not liberal,” Matt Angle, an influential Democratic strategist in Texas, told me. “Cuellar is seen as a stronger general election candidate.”

In the end, Cuellar and his corporate backers carried the day (one marked also by the Uvalde school massacre), albeit by a hairbreadth margin. Nevertheless, Dyana Limon-Mercado, the executive director of Planned Parenthood Texas Votes, points to a steady shift in favor of reproductive rights in the region, as exemplified by a Texas Senate seat near Cuellar’s district where a pro-choice female candidate won the Democratic primary to replace a longtime antichoice incumbent. Among other examples, she cited the grassroots pressure that killed a proposed ordinance to make the city of Edinburg a “sanctuary city for the unborn.” “The sentiment of ‘mind your own business’ is actually of more value for Latinos than being anti-abortion,” she told me. “Our family business is our family business.”

Given the impossibility of garnering sixty filibuster-proof votes to pass abortion protection (and Biden’s refusal to discard the filibuster), the intentions of either a Cuellar or a Cisneros are irrelevant. The battle for abortion rights must be fought in the states, where Republican legislators have been busy conceiving ways to make it ever harder for women to access the right conferred by Roe v. Wade all those years ago. In addition to measures like the civilian-enforced bans in Texas and Oklahoma are laws reminiscent of the arbitrary requirements imposed under Jim Crow to keep black people from voting. Ostensibly concerned with patients’ safety, they serve primarily to make getting or providing an abortion more onerous. Eight states, including Michigan, specify that corridors in abortion clinics must be a particular width.

The ubiquity of local anti-abortion laws is all the more striking given equally ubiquitous polls showing that abortion in some form enjoys wide support, though the level varies according to the circumstances. Some 60 percent of Americans, for example, told Gallup that they support abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy, a number that dropped to 28 percent regarding abortion in the second trimester. Many people do not understand the restrictions already in place where they live. In the twenty-two states currently enforcing abortion restrictions, 70 percent of those polled were either unaware or unsure that these measures were on the books. Research commissioned last December by the mainline polling firms ALG Research and Hart Research Associates on behalf of Planned Parenthood and similarly minded groups reported that 80 percent of voters said they were “more likely to vote for a Democrat who favors leaving abortion decisions up to pregnant people and their doctors.” A mere 9 percent were more likely to support a Republican who favored making abortion illegal, including in early pregnancy. Such findings jibe with others reporting a steady majority in support of abortion rights over the years. This glaring contradiction is most obviously due to Republicans’ gerrymandering efforts, although Democratic equivocation on the issue has not helped. Republicans, for example, make up half of registered voters in Oklahoma, and half of Oklahomans say that they think abortion should be mostly legal. Yet in May a state legislature that is four-fifths Republican passed the strictest abortion ban in the country.

“Be careful about these polls, because they show you all sorts of things. But the most important poll is how people vote,” Richard Viguerie informed me from his Virginia farm a few days after the leak. If any one man can be credited with creating the conservative movement that now exercises such power over the Republican Party, it is the eighty-eight-year-old Viguerie. Born in Pasadena, Texas, the year FDR took office, and an active right-wing partisan all his adult life, he pioneered the potent weapon of political mass mailing in the late Sixties. When I called, he was drafting the message that he thought his tight-knit network of like-minded conservatives should deploy in branding Democrats as the party of open borders, defunding the police, suppression of free speech, and “abortion on demand.” “We are in a cold civil war,” he told me more than once. “Lock and load.” Over the years he has composed and dispatched “tens, hundreds, of millions” of letters promoting the anti-abortion cause, thereby eliciting waves of small donations that have earned him the title of “funding father” of American conservatism. For him, the Alito opinion represents not merely a long-sought victory, but an opportunity for further advances in the domestic civil war on such matters as sex education in schools, immigration, liberal control of the media, and of course abortion.

“What was the most important single event in the 2016 election that caused [Donald] Trump to win?” he asked rhetorically. “The death of [Supreme Court Justice Antonin] Scalia. In essence, that put the Supreme Court on the ballot.” Given that the 2016 election was decided by paper-thin margins in rust-belt states such as Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan, Viguerie suggests that it was abortion that put Trump in power and that cemented total Republican control of twenty-three state governments. While Planned Parenthood affirms that “Attacking Republicans on Abortion Will Be Key to Winning in 2022,” Viguerie draws the opposite conclusion. “People argue about when it should be legal, when it should be illegal, this tri-semester, that tri-semester,” he explained, “but the key question is: How do they vote?” Republicans win single-issue abortion voters by a huge margin, he claimed, with the implication that the Alito leak would instill further determination in that section of the electorate. (Indeed, a Politico/Morning Consult poll taken immediately after the leak reported that 35 percent of registered voters say it’s more important to vote for a candidate “who agrees with my stance on abortion, even if they disagree with me on other issues” than the other way round.)

Warming to his theme, he pointed to what he said is another under-reported feature of abortion election politics: “soft Catholics, social justice Catholics who unfortunately vote Democrat—roughly sixty-forty over the entire twentieth century. That’s changing now,” Viguerie, an observant Catholic, said happily. “Obama carried the Catholic vote, but then Trump carried it fifty-two to forty-five. . . . You got to believe that a lot of people who normally vote Democrat said, because of the Supreme Court, I just can’t do it.” For them, he thinks, overturning Roe is a beginning, not an end.

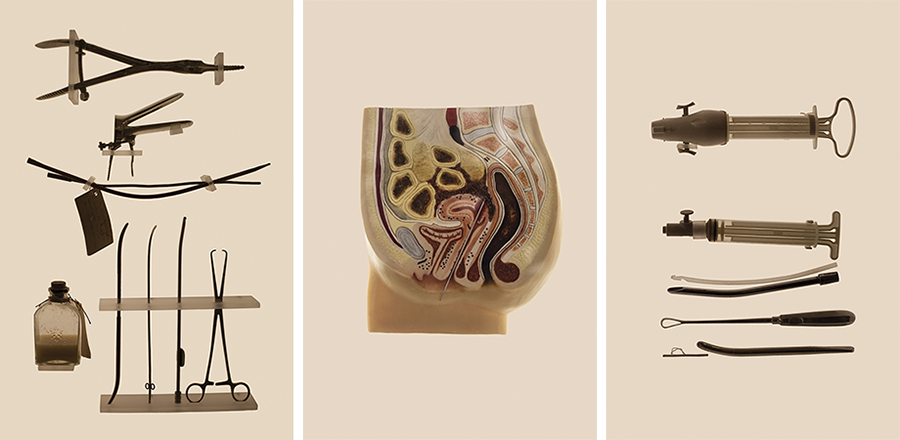

Left to right: Tools used for illegal abortions in the twentieth century; a model of an abortion procedure involving a knitting needle; surgical instruments used for abortions between 1900 and 2004. All artwork by Laia Abril, from On Abortion © The artist

In view of such confidence, it is worth examining how abortion bans were reversed in Ireland in 2018 and in Argentina, another Catholic country, two years later. Both outcomes were the product of intense campaigns. Though naturally tailored to differing cultures and circumstances, they shared a focus on women’s health and welfare. The Argentine movement invoked a powerful precedent: the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, women who, under the fascist military dictatorship that ruled from 1976 to 1983, demonstrated weekly in Buenos Aires over the disappearance of their children at the hands of the regime’s death squads. Their symbol was a white handkerchief, and the abortion rights movement that mobilized after the fall of the regime adopted green handkerchiefs in tribute to their predecessors. “It’s a pretty ballsy act under a military dictatorship, to be walking around and saying, bring us back our children,” Anat Shenker-Osorio, a progressive communications specialist and podcaster who has studied the Argentine and Irish campaigns, told me. By calling their campaign la revolución de las hijas, the revolution of the daughters, the new movement was saying “we’re doing this so that the next generation can be better than this one,” she explained. While anti-abortion partisans, including the church, coordinated “pro-life” messaging, complete with the traditional magnified images of fetuses, the women’s campaign highlighted the toll of women dying from illegal abortions with the slogan “Not one less,” and hung green neon coat hangers bearing the names of opposing senators on trees in front of the capitol. In December 2020, the Argentine congress voted to legalize abortion. This historic development has since been echoed in Colombia and Mexico—a counterpoint to the common notion that Hispanic women are reflexively conservative in such matters.

Smyth, the co-director of Together for Yes, the effort to repeal the Irish amendment, explained to me that they adopted a different approach from earlier campaigns. Instead of arguments that pitted the fetus against the woman, they stressed that “the person we have in our sights is a living woman who could be your mother, your sister, your daughter, your work colleague, your friend, or the woman who lives down the road. We really shifted the ground.” Instead of “choice,” which, according to the group’s research, summoned negative memories of angry arguments, they emphasized “care”; “compassion—you don’t have to agree, but can you understand that someone may need to make a different decision in their life”; and “change.”

Shenker-Osorio, who advised Smyth’s group in its early stages, emphatically agrees. She argues that choice as a thematic message is a mistake because of its associations with consumer decisions. “So, vanilla or chocolate, decaf or caf, skim milk or soy, cases where the decision made is something of little consequence,” she said. “There is this default idea by lots of people that people who make an abortion decision are taking it lightly, or using it as contraception.” Themes of care and compassion send a more powerful, positive message—one that says “in an arena in which the opposition has purportedly claimed life, ‘No, we’re the ones on the side of saving lives. We’re the compassionate ones!’ ” Some American activists are already putting this message into practice. Supermajority, whose founders include the former Planned Parenthood director Cecile Richards, is distributing “Someone You Love,” a video featuring women and families in ways that evoke compassion, such as a woman who wants a baby but cannot survive the pregnancy or a cancer patient too sick to bear a child.

Betsy Coffia’s story of her shift away from her youthful convictions suggests the persuasive power of such themes. She recalls a young married woman in her church who, faced with a life-threatening ectopic pregnancy, opted for an abortion, a decision her fellow church members deemed wrong. “But her life was at stake,” Coffia said. “That introduced gray to the black-and-white right-to-life view I’d only ever heard my whole life.”

Whatever message turns out to be most effective in the maelstrom of American abortion politics, the Alito leak has generated one encouraging sign for women’s rights advocates. Although Oklahoma and Louisiana have determinedly reinforced their abortion bans, there are indications elsewhere of a certain tactical caution. For example, Mitch McConnell (whom Viguerie derides as a “RINO”—a Republican in name only—ever ready to betray the conservative cause) has been careful to play down any notion that his party would pass a national abortion ban if and when Republicans control the Senate. “It’s been interesting to see the lack of conversation” among Wisconsin Republicans, Neubauer remarked. “They know that this is not popular. I think they’re going to do what they can to avoid talking about it with voters who are moderate, who they need to win.”

Across the lake in Michigan, Coffia had a more pungent analysis: “They’re the dog that caught the car—a car full of angry women.”