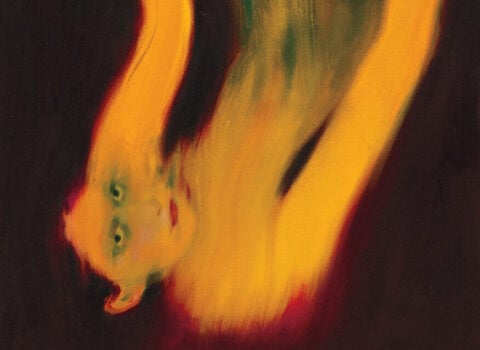

Cowboy Picture, 2003, a painting by Ed Ruscha © Ed Ruscha.

Charlie Siringo was that rare thing, a cowboy who wanted to tell you about it. Your archetypal ranch hand is gruff, laconic, but Siringo didn’t know when to shut up—he somehow glad-handed his way through one of the most stoic, lawless epochs of the nineteenth century. When he wasn’t making rope or lighting out for the territory, he was working on his memoirs, writing a pseudonymous gossip column, and honing his campfire bonhomie. “Charlie liked almost anyone he met who didn’t mistreat a horse,” Nathan Ward writes in Son of the Old West: The Odyssey of Charlie Siringo: Cowboy, Detective, Writer of the Wild Frontier (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28). It’s thanks in part to his volubility that the old west became the Old West, the kind of ur-place that one could be a son of. In his dotage, he moved to Hollywood and lent his presence to the first horse operas.

Born on Texas’s Matagorda Peninsula in 1855, the precocious Siringo spent his youth lassoing sand crabs with fishing line and walking barefoot to the schoolhouse. When the Civil War heated up, his teacher, an Illinois man now behind Confederate lines, abruptly canceled classes and quit town, leaving Siringo “doing nothing and studying mischief,” as he wrote in A Texas Cowboy, the first of several memoirs. He watched his friend’s dad blow himself up by lighting an unexploded cannon shell in his front yard. A lodger took him on his first cattle drive when he was twelve. He remembered donning the uniform—“broad sombrero, high-heeled boots, Mexican spurs”—and knew from then on “the dignity of a full-grown man.”

But rustling cattle held plenty of indignities. On the trail to Kansas’s thriving beef markets—hundreds of miles “tramped hard and solid,” Siringo wrote, “by the millions of hooves”—the animals would be spooked by just about anything, Ward writes: “someone shaking out an empty slicker, the clatter of a frypan, flash of a bull’s-eye lantern, or a wolf’s keening howl.” Obstinate steers had their eyelids sewn shut and cowboys slept in shifts under the stars, rubbing tobacco juice in their eyes to stay awake. In bad weather, they sang to the cows to soothe them.

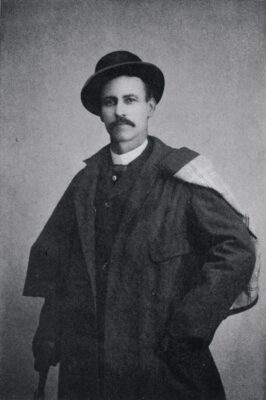

A photograph of Charlie Siringo from the 1890s

As with much of Ward’s source material, Siringo’s life can feel retrospectively absurd, too authentic to be real. The man’s gestalt was designed for accompaniment on harmonica. He saw herds of buffalo so dense they seemed to Siringo to resemble a “black streak of living flesh coming down off the north plains.” You can read Ward’s book profitably for the horses’ names alone—Dandy Dick, Glen Alpine Jr., Satan, Whiskey-peat, Beat-and-be-damned—or for its cameos from the frontier’s marquee names. Siringo once gave a meerschaum cigar holder to Billy the Kid; Bat Masterson is said to have chucked beer glasses at him in a barroom brawl.

His story reached new heights of improbability in 1886, when he took a job chasing down lowlifes for Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency. Now the cowboy was fighting crime. The Big Eye sent him undercover for months at a time to sniff out train robbers (including Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch), mine salters, anarchists, and sundry ne’er-do-wells. One of Siringo’s contemporaries outlined his duties:

If he had to spend a week of nights in some hurdy-gurdy dance hall, drinking and carousing with the gang, in order to get evidence against one of them, he went the limit, drank, gambled, shot out the lights and played bad-man—and then, suddenly he had his man in jail, and no one knew how it happened.

Adopting aliases such as Leon Carrier and Charles T. LeRoy, Siringo carried fake letters, fake newspaper clippings, and a pocket watch engraved with fake initials. He would flirt with criminals’ sisters or daughters to get information out of them. His talent for false friendship verged on the sociopathic. Camping with a rogue dynamiter, Siringo stuck elk horns into two neighboring peaks and claimed to have named the mountains in honor of their manful bond. Six hundred miles later, he had his companion arrested. Desperate to prove he wasn’t a double agent, he avowed in one of these fake documents that working for Pinkerton’s was “the lowest and most degraded calling any man can follow”—and one wonders if he didn’t believe it.

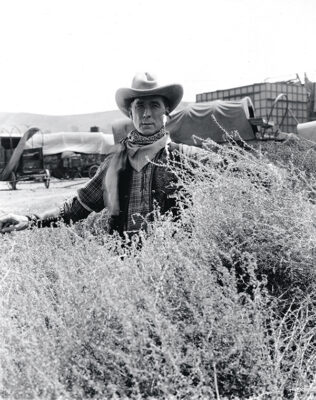

A still of William S. Hart from the 1925 silent film Tumbleweeds. Courtesy Seaver Center for Western History Research, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Siringo arrived in Los Angeles in 1923, in time to see the hollywoodland sign go up. Two of his books, A Texas Cowboy and A Cowboy Detective, gave him cachet among writers of detective fiction, such as Dashiell Hammett, and among “cowboys seeking movie work.” Siringo lived modestly and hung out at the Water Hole, a nostalgic bar where “chewin’ he-men still find solace,” as a reporter had it, in their “$7 plaid wool shirts.” He cozied up to Will Rogers and William S. Hart, whose movies, another cowboy opined, emblazoned “the West as the Westerner hopes to have it remembered,” and who regarded Siringo as an eminence. Hart gave him a walk-on role in Tumbleweeds, the director’s final film. Siringo had trekked across desolate stretches of America; he consorted largely with foul-breathed malcontents who spoke through their revolvers. In Ward’s handsome telling, though, it’s only in the dark of the movie house, watching himself in a crowded saloon on the silver screen, that he appears truly alone.

In the mid-Fifties, as the movie colony continued to turn rawhide violence into leathery Western myth, Eugene Stoner was building something so lethal that it threatened to destroy mythology altogether. Stoner was the chief engineer at ArmaLite, a gun concern whose logo featured a Pegasus in crosshairs. In a squat brick office less than a mile from the Paramount studio lot, he invented the AR-15. The weapon now synonymous with mass shootings was born in Hollywood. The first man to test-fire it, excepting ArmaLite employees, was John Wayne.

In American Gun: The True Story of the AR-15 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $32), the Wall Street Journal reporters Cameron McWhirter and Zusha Elinson write that America’s obsession with the Old West influenced its military strategy. As communism appeared to run rampant, effective counterinsurgency called for

clandestine missions and rapid-strike attacks by small mobile groups or individuals with light, powerful weapons—the modern version of gunslingers and cavalry battling Indians on the frontier.

Stoner aspired to arm the cowboys of tomorrow. Studying mass-producible forebears like the Nazi Sturmgewehr 44, he developed a rifle made of space-age aluminum, fiberglass, and plastic, powered by an ingenious system that deployed the gas from exploding gunpowder and used it to reload the gun. The result weighed about seven pounds, shot many bullets quickly, and “looked a little far-out,” he said.

Hollywoodland sign, 1923 © Stephen and Christy McAvoy Family Trust. Courtesy Hollywood Photographs

Historians of gun design compared Stoner to Mozart. Today he remains the patron saint of “couch commandos,” as manufacturers refer to their prized demographic. But in life he made a dim luminary, with his head-shop surname and his buttoned-up mien. He wore clip-on bow ties and ate at IHOP. On a blind date, he once demonstrated how to use a slide rule. He never spanked his children and when losing his temper would say, “Boy that frosts me.” In one of the great understatements of the twentieth century, he described his interest in guns as “kind of a hobby that got out of hand.”

Investigators tried his AR-15 on castrated goats (they exploded), sacks of pig viscera (they exploded), and Burmese coconuts (they did not explode, lacking “enough milk inside to produce the desired results,” a tester wrote). In 1962, South Vietnamese Special Forces secretly tested the gun against the Viet Cong. “One round in the head—took it completely off,” their report read. The AR-15’s method of firing ammunition so ravaged human flesh that Swedish politicians felt its use constituted a war crime. By 1966, after the United States had entered Vietnam, the Pentagon was besotted enough to order 403,905 of the rifles, rebranding them as M16s—a coup for Stoner, who believed his gun would never win over a bureaucracy that favored firearms developed in-house. “To those ‘Humanitarians’ who think enemy soldiers should be killed neatly and politely,” a reporter wrote, “the M16 is a ghastly weapon.” Unfortunately, its ghastliness extended to its design, which the Army had maladroitly tweaked to meet production demands: a propellant change caused it to jam constantly. Grunts lay dead “with their rifles dismantled next to them or the cleaning rods by their side,” McWhirter and Elinson write. The Department of Defense buried the error.

The rifle’s civilian debut was no more auspicious. In 1963, having bought the patent, Colt began to market “the Sporter,” a nonmilitary AR-15 with a smaller magazine and no fully automatic mode. Hunters and marksmen scoffed; with its hellfire spray, the Sporter was blatantly unsporting. The rifle seemed doomed to “obscure novelty,” McWhirter and Elinson say, and Colt produced only about 2,400 in the first year.

And yet, in the year 2006, there were nearly two hundred thousand AR-15s built for sale in the United States. The following year, when a prominent outdoorsman argued that there was “no place for these weapons among our hunting fraternity,” he occasioned such responses as “Go suckle on Hillary Clinton’s bosoms a little more, you uninformed fucktard.”

That forty-year arc contains the whole sick American rainbow. Disaffected white supremacists; survivalists; gangland drive-bys; Rambo; NRA fearmongering; a Bushmaster ad bearing the slogan consider your man card reissued; limited-edition Y2K-themed ARs, bronzed like baby shoes. The rifle’s dramatic rise in popularity, according to McWhirter and Elinson, can be traced to 2004, when the Clinton-era assault-weapons ban expired and post-9/11 patriotism reached a fever pitch. By then, gun advocates had popularized the AR-15 as a “symbol of defiance against federal overreach,” and pop culture was awash in images of beefy Special Forces guys lugging assault rifles in the name of freedom. Sales soared. From here, the book’s reporting astonishes enough to offset its sole potential flaw: we all know how this story ends, or how it refuses to end.

A U.S. soldier with an AR-15 in Vietnam, 1963 © AP Images

The first mass shooting that involved an AR-15 occurred outside an Oregon nightclub in 1977. American Gun’s coverage of this era accrues with devastating force, particularly as one realizes, with shame, how many deaths have slipped one’s mind. Reading the book after Son of the Old West, it seemed to me that the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history, which claimed fifty-eight lives during a 2017 country music festival at the Mandalay Bay Resort in Las Vegas, marked the AR-15’s total perversion of the Western ethos that inspired it—guns, gambling, guitars. Siringo and his ilk fondled their Colt 45s with a misty-eyed romance that eventually led to our evacuated language of “active shooters” bearing “modern sporting rifles,” words that seem handpicked to spare the guns’ feelings. They evoke sweat-wicking athletic wear more than the pooling blood of corpses pulped by bullets. Visiting Mandalay Bay, McWhirter and Elinson found that the resort makes no formal reference to the massacre. They’ve simply renumbered the hotel floors to skip the thirty-second, where the gunman launched his attack.

Similarly, Stoner preferred to steer conversation toward his gun’s technical specifications rather than dwell on its awesome capacity to kill. He died in 1997, nearly two years to the day before Columbine. His invention would soon be fetishized as a “cool-looking weapon,” to quote one manufacturer, that makes introverts feel “edgy.” But Stoner, too, felt the romance; in his twilight years, he nursed those fantasies that must be peculiar to a prosperous gunmaker. He dreamed of erecting a house of anodized aluminum, his beloved material, atop a tall pedestal north of Miami. Having served in the Marines as a young man, he requested burial at Quantico, with a twist: the honor guard should salute him with long bursts of automatic fire from their M16s. He signed his letter semper fidelis. The Marines obliged.

“Marilyn Monroe in the Sunshine,” by Frank Worth © The artist. Courtesy Globe Entertainment and Media Corp

As far as detectives go, Charlie Siringo walked so Freddy Otash could run, loot, and pop Dexedrine. He’s the Tinseltown private dick who narrates The Enchanters (Knopf, $30), James Ellroy’s lush, manic novelization of Marilyn Monroe’s death and all that was hushed up around it. The book contains more than a kernel of truth: Otash was a real fixer known for his A-list imbroglios and disreputable methods, including “cramming an unbelievable assortment of electronic gadgetry into an ordinary sound truck,” the Los Angeles Times wrote in 1971, describing what was then state-of-the-art surveillance. He met Ellroy a few times and bragged that he’d bugged Peter Lawford, JFK’s brother-in-law. He said he’d heard a tape of the president and Monroe having sex.

Ellroy called Otash a “bullshitter,” and The Enchanters runs on his bullshit—it embroiders an embroiderer. At the outset, Jimmy Hoffa hires Otash to spy on Monroe, mere months before her overdose, and generate a scandal sheet about her misdeeds with the Kennedy boys. Snooping around her Brentwood hacienda, he finds too many loose ends: forty grand in cash, a wardrobe belonging to a much larger woman, a list of her lovers alongside the main switchboard number for the sheriff’s office. There’s also a Jackie Kennedy voodoo doll rife with pins, and a secret compartment containing “fuckee-suckee pix” coated in semen. Underbellies don’t come any seamier than this. From there, the plot is off to the sordid races.

Ellroy’s last novel, Widespread Panic (which also starred Otash), has been described as “camp noir.” The Enchanters continues along the same lines and throws some erotic fan fiction into the mix. “We’re all fan-club fools run amok,” Otash says of himself and his fellow Monroe obsessives. Like Brian De Palma in Blow Out, Ellroy goes in for loving close-ups on the tools of the eavesdropper’s trade, the phone taps and hidden bugs. But they can’t compete with “scent and sensation,” Otash says: “I wanted to touch things that touched her. I wanted to be where she got lonely and cut loose.” When Otash has a porny nightmare about his tradecraft, Ellroy’s rat-a-tat sleaze is pitch-perfect:

Wall wires, rug clamps, refitted phone jacks. They’re changing colors and starting to fray. They’re squirming. They’re untangling out in plain view.

They wiggle. Bore holes leak Spackle. Discolored Spackle—alive with a glow.?.?.?. Tap wires pop through handset perforations. Mike installations explode.?.?.?.

They’re moving. They’re pure combustion. They’re out to set me aflame.

The detective’s bag of tricks is all voyeurism, like Hollywood’s. The town that gave us the Western and the AR-15 was—is—overrun by profane megalomaniacs who had no business shaping the nation’s dream life, but did it anyway. Curious about the historical Otash, I dug up a fawning 1959 profile from the Los Angeles Mirror, which offered this choice detail: “The only item lacking to keep him from becoming a TV hero,” it reads, “is a gun strapped under his shoulder.” Riding high in his Cadillac Eldorado convertible, Otash had decided he didn’t need to carry one.