In June, days before Harper’s contributor Bernard Avishai brought together a panel of experts for a conversation about the prospects of a lasting resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped while hitchhiking in the West Bank. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu publicly blamed Hamas for the abduction. While these events were much on the minds of our panelists, we encouraged them to remain focused on larger trends rather than more immediate concerns. Shortly after the discussion took place, the bodies of the three teenagers were found by an Israeli search team, and a Palestinian teenager was murdered in East Jerusalem in an apparent revenge killing. Hamas began launching rockets into Israel, and Israel bombed targets in Gaza. As this issue went to press, Hamas turned down a ceasefire brokered by Egypt, and Israel sent ground troops into Gaza. Our participants knew none of this at the time, but they are all longtime residents and students of the region, in which such outbreaks of violence are sadly familiar. They offer invaluable insight into how the conflict arrived at this point and where it might be headed.

A photograph of the Palestinian suburb Al Eizariya, now divided from East Jerusalem by a security wall, from the multi-photographer project This Place, which explores the current state of the conflict between Israel and Palestine. A selection of images from the project will be on view next month at DOX, in Prague.

The following forum is based on a conversation that took place at the Jerusalem YMCA on June 15.

Participants:

BERNARD AVISHAI

is the author of The Tragedy of Zionism and The Hebrew Republic. He teaches at the Hebrew University and Dartmouth College.

DANI DAYAN

was the chairman of the YESHA Council of Jewish Communities in Judea and Samaria from 2007 until 2013. He now serves as its chief foreign envoy.

FORSAN HUSSEIN

is the CEO of the Jerusalem YMCA.

EVA ILLOUZ

is a professor of sociology at the Hebrew University and the president of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design.

BASSIM KHOURY

is a pharmacist and industrial entrepreneur who has served as president of the Palestinian Federation of Industries and as economic minister for the Palestinian Authority.

EREL MARGALIT

is a venture capitalist and a member of Knesset from the Labor Party.

DANNY RUBINSTEIN

is a journalist who has covered Palestinian issues for more than forty years. He teaches at Ben Gurion University.

KHALIL SHIKAKI

is the director of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research in Ramallah.

PART ONE: “WE LIVE SO CLOSE TO EACH OTHER, YET WE KNOW SO LITTLE ABOUT EACH OTHER

BERNARD AVISHAI: First of all, thank you all for coming. It’s an honor to be in a room with so much talent and so much experience. I’m going to do something very un-Israeli: Everybody gets to finish their sentences. We want to focus on the future, including long-term demographic trends — not just births and deaths, but also growth, education, and urbanization. It is also important to have a bit of historical perspective, and I’d like to start by asking Danny Rubinstein, who has been covering these issues for a long time, to provide some of that. Danny?

DANNY RUBINSTEIN: I’m a newspaper man. I’ve covered the Palestinian territories since 1967, right after the war, first with Davar newspaper for more than twenty years and then with Haaretz, for almost twenty years. Bernie said that we’ve gathered here talent and experience. I belong to the experience department.

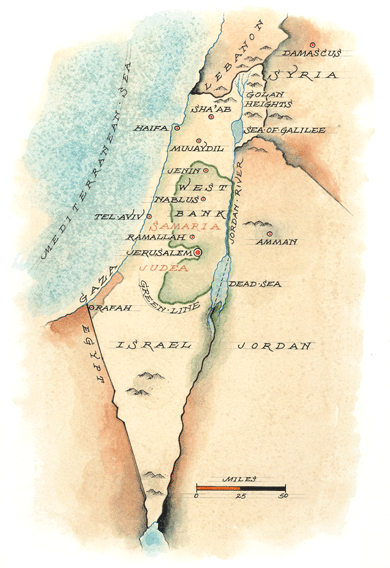

What’s the major difference compared with, let’s say, the first twenty-five years I covered the area? Until 1992 or ’93 there was not one checkpoint between Rafah on the Egyptian border and the Golan Heights. Not one checkpoint. There was freedom of movement for everybody. When I worked for Davar, I used to accompany two or three Israeli cabinet members every week who were visiting Arab cities. Moshe Dayan went once or twice a week to Nablus. Cabinet members from all parties came to every city, every village in the West Bank. I was with them. There was a sort of competition — who could make more visits and who would have more friends among the Palestinians.

So this is the major difference for me. Of course, there’s bitterness, hatred, frustration, on both sides. But it’s very important to say that without freedom of movement you cannot run anything in this country. And I was glad, when I read Dani Dayan’s article,* that he said: Let’s begin with freedom of movement. When there was freedom of movement, there were about 200,000 Palestinian laborers working in Israel. I’m hesitant to say they made good money, but the standard of living went up dramatically in those years. Now we have 300,000 or more foreign laborers — from Africa, from Asia, from all over the world — and we don’t give those job opportunities to our neighbors. This is the major change that I’ve seen since 1967 — really, since ’91 or ’92.

BASSIM KHOURY: One result of what you’re talking about is the complete schism between the two sides; we live so close to each other, yet we know so little about each other. You used to know us as laborers, doing the labor that Israelis didn’t want to do, and now you know us as homicide bombers. And we only know you as colonists and occupiers. What’s amazing but often ignored is that it’s been almost fifty years. In Dani’s article that he’s so proud of, which was published in the New York Times, he mentions a fifty-year-old Palestinian man being humiliated while having to deal with an Israeli soldier half his age, just to carry out mundane daily chores.

DANI DAYAN: I criticized that.

KHOURY: Yes, yes, you criticized that. But you failed to mention that this fifty-year-old man has lived almost all his life under occupation and has been continuously humiliated for almost half a century! So you have lived all your life in a certain situation, yet you know so little about the person in front of you. When we were allowed to travel, when there was no wall separating us, I used to take my employees to the Sea of Galilee on day trips to swim. And I would ask: “How many of you have ever crossed into Israel?” We are speaking before the First Intifada, when you could just get into your car and in two hours be in Haifa or in Tiberius. The number was never more than 10 percent.

Simply put, for almost half a century we Palestinians have been living in a big prison. We all feel imprisoned. A majority of Gaza residents have never left Gaza. Almost no young people — and they are more than half of the population — almost none have ever left Gaza. You’re speaking of a territory smaller than Greater Tel Aviv. One and a half million people locked in an area of 365 square kilometers. They believe Gaza is the center of the world. The situation is very much the same for young people in the West Bank. Even at this time of the global village, people are becoming less and not more open to what’s happening around them.

The major effect of the current situation, which people like me have been warning about for years, is that the moderate core of societies, the people who do know better, are voting with their feet. They are leaving. And as a result, who’s staying? The extremists.

DAYAN: I relate completely to many of the things that Bassim has said. Without asking him, I think that the main difference of opinion is who is to blame for it. Bassim, I suppose, will say the occupation, the so-called occupation. And I will say the political and moral choices that Palestinians made during the past decades. Let’s take, for instance, Gaza. I haven’t been in Gaza since the disengagement, obviously. But I assume that the human conditions in Gaza are quite harsh. I agree with Bassim there. But the truth is that the Palestinian residents of Gaza were given a historic choice seldom given so clearly to a group of persons. They had the ability to decide whether they wanted Gaza to be a Middle Eastern Singapore or a Middle Eastern Somalia. If they had decided that they wanted Gaza to be a Middle Eastern Singapore, I don’t have the smallest doubt that Israel would have contributed all it could to that effort.

But they made a cold-blooded decision that they prefer Gaza to be a Middle Eastern Somalia, that they want Gaza to be a launching pad for aggression against Israel, that they want almost every single penny, every single euro, every single yen, every single pound that was generously contributed to Gaza by the international community not to improve infrastructure, not to build hospitals, not to build schools, but to amass armaments against Israel.

AVISHAI: We are trying to talk about long-term issues more than who is to blame for what. I’m a little concerned about degenerating into a back and forth over —

DAYAN: Okay, but you have to understand the background in order to do that.

AVISHAI: We will, I’m sure, get into the question of who is to blame. I would like you to talk about the future a little bit.

DAYAN: I have described a plan for what I call peaceful nonreconciliation, because reconciliation between Israel and the Palestinians — or between Zionism and the Palestinian national movement — is not reachable right now. Incidentally, I think this is the most accurate definition of the conflict. It’s a conflict between the Zionist movement and the Palestinian national movement. A national-liberation movement, the Zionist movement, which sees itself as reclaiming its homeland, and a national movement like the Palestinian movement, which sees Zionism as a colonialist project, don’t have a reconciliation point.

A still from Infiltrators, a video by Khaled Jarrar, which documents the experience of Palestinians attempting to cross into Jerusalem from the West Bank. It is on view now as part of Here and Elsewhere, an exhibition of con-temporary Arab art at the New Museum, in New York City. In July, Israeli officials denied Jarrar exit from Palestine to attend the exhibition’s opening © The artist. Courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris, and New Museum, N.Y.C.

Therefore, what we have to do is invest our energy in the question: How do you handle life as normally as possible under the abnormal circumstances of the lack of reconciliation? Ten years after the Second Intifada, Israel has to start to heal and take calculated risks. And I’m very much in favor of this. If I can offer three main points, the first one is, as Danny said, freedom of movement, complete freedom of movement. I want to go back to those days that you just mentioned, when my neighbor in the Palestinian village of Azzoun could wake up in the morning and tell his children, “It’s a very nice day today. Let’s go to the beach in Tel Aviv.” No permit needed.

The second one is employment. I want to see high-tech professionals from Ramallah in the startups of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem — not only blue-collar labor, as Bassim mentioned. I want to see joint industrial parks. The third one I think is the most problematic but maybe the most important: the complete rehabilitation of the refugee camps. The fact that sixty-five years after the creation of the refugee problem the fifth generation still lives in squalid conditions maintained by a corrupt U.N. agency whose task is to perpetuate the refugee status — I think it’s a disgrace. It’s a disgrace for the Palestinians and it’s a disgrace for us.

If all of that is done, it’s not a solution to the problem. The conflict will be as unresolvable as it is today. But it will make a dramatic change in the lives of real people. This is the option we pose now. Do we want to do nothing but engage in escalating diplomatic warfare with outbursts of violence, or come to grips with the conclusion that the conflict does not have a solution right now and make out of it the best things we can?

EREL MARGALIT: I don’t buy that premise. You know, I come from the start-up-nation generation. I have been an entrepreneur for about twenty years and started many companies here in Jerusalem. My generation in Israel is moving into political life, and we do not accept some of the premises that the previous leadership brought to the table. One premise is that the situation is not solvable or that we can focus on economic advances and give up on political agreements. Granted, we have a very tough situation here. But no victory can be achieved if you don’t maintain optimism. I am convinced that with this attitude we will have a two-state solution within five or ten years.

Sometimes I think it’s healthy for my fellow Israelis to look at the Middle East and remove ourselves from the picture for a moment, just for perspective. And when you look at what’s going on around us, you see a lot of challenging situations — in Syria, in Lebanon, in Iraq — but you also see a few rays of light that are interesting and worth exploring. This is especially true with entrepreneurs, who view one another through a different prism, across different cultures. You see a very entrepreneurial community in Jordan of people who were not connected to the administration. You’re seeing in Egypt that the Arab Spring is not just a democratic process; it’s also an economic process. And you see pockets of innovation, especially among women, around Cairo. You see places like Tunisia, where the Arab Spring has brought not only frightening events but also the first real democracy.

Although politicians are having a hard time finding models of cooperation, in the business community we have a few of these models. If you want to talk about bleak situations — in 2002 you had about two dozen suicide bombers coming just from the city of Jenin alone. I was in the Golani Brigade, and we worried about it all the time. Today, in the governorate of Jenin there is a big discussion with the Israeli region of Gilboa, which is right next door, about creating an industrial zone that would span both. And just recently I saw that they are marketing a tourist package in Germany: three days Jenin, three days Gilboa.

If you drive half an hour north from where we are and you stand in the middle of Ramallah, you see thirty-five cranes. You see another society that’s trying to build a country. To me, it’s not a question of whether this is going to happen. I am sure it is going to happen. I’m just looking for the right people to lead it and want to be involved as part of it.

EVA ILLOUZ: Erel, it seems to me that your view that there is great possibility for change has much to do with being involved in the process. I wonder if such involvement does not create the illusion of movement. There is a kind of asymmetry between those who are involved in what is happening on the ground and those who are spectators — or victims — of it. I view myself as belonging to the second group. Like most Israelis, I am a bystander, and I do not see the things you see. Those actively involved in the two populations fall prey to an illusion that many changes are possible because they confuse movement and change, whereas people like me fall prey to the opposite illusion: that things are more static and bleaker than they actually are, only because most of the changes abundantly covered by the media are not palpable.

AVISHAI: So you see negative trends?

ILLOUZ: I see conflicting trends. I define myself as being at the juncture between diasporic Jews and Israeli Jews. I was born in Morocco, but I grew up largely in France and spent many years as an academic in the United States. I arrived in Israel after the age of thirty and have never really been able to become a full-fledged sabra. As someone who still identifies with the Diaspora, I often feel like a stranger to myself as an Israeli. This, it seems to me, is a breach in Israeli identity that is going to grow increasingly and reshape the relationships between Jews and Israel. Remember that originally the vocation of the country was not only national but transnational as well. Israel was to represent the unity of the entire Jewish people. That was very much Theodor Herzl’s objective, the initial objective of much of Zionist thought: not only to build a state but to unite the entire Jewish people. For a long time Israel’s relationship with the Jews outside Israel rested on that assumption.

We are starting to see this change dramatically. One example: A group of intellectual Israelis have emigrated to Berlin and claimed they were returning to their real roots in Europe. For those of us who wanted to be Jewish and yet did not relish separating ourselves from non-Jews, Israel was a universalist solution to our dilemma. Israel was the solution to the contradiction between particularity and universality. We are witnessing a complete reversal of this dynamic: a significant faction of the Jewish people, inside and outside Israel, who view themselves as the bearers of universalist values, think that such universalism can only be achieved outside Israel. In the past few years it has become painfully clear that Israel has in fact become a particularistic, ethno-religious project. In the first Knesset, there were sixteen members from the only distinguished religious party, the United Religious Front. Today, religious parties constitute a quarter of the Knesset — thirty out of 120 Knesset members. That’s without counting religious members of the Likud party, such as Tzipi Hotovely and Moshe Feiglin. Over the past decade, the number of students in ultra-Orthodox elementary schools has grown by almost 60 percent, while the number of students in secular elementary schools has remained basically unchanged. The forecast is that by 2025, 35 percent of all children entering elementary schools in the Hebrew education system will be ultra-Orthodox.

These changes are reflected in the public rhetoric, which has become far more religious, as was obvious when Netanyahu demanded that Israel be recognized as a Jewish state. Such a demand had never been made before. Politically, Israel is a different entity. Many Jews have stopped identifying with Israel, not because they are assimilating, not out of apathy, but through a conscious, deliberate belief that Israel jeopardizes the moral core of their identity. The new trend is toward the isolation of Israel not only from the world but from an increasingly large faction of the Jewish people. This is not only because of the way in which Israel relates to the Palestinians and the Palestinian issue but also because of the ways in which Israel has treated Jews themselves. The state has missed a very important opportunity to be a platform in which all the plurality of forms of Judaism could meet and flourish. In fact, Judaism has been less able to flourish in Israel than in Christian countries after World War II because of the control of Orthodox Judaism in all major state institutions and its legal framework.

And this is not disconnected to the issue we are discussing. Israel is unable to solve the conflict with Palestinians for the same reasons it is unable to provide a platform uniting Jews: the country is premised on a primordial, religious, ethnic vision of itself which prevents it from articulating a universal language of rights. Ultra-Orthodox, various religious factions, and settlers have in fact reshaped public rhetoric, schools, and key state institutions, thus making it increasingly difficult to hold on to a liberal, universalist vision of humanity from which grand projects like peace and pluralism can emerge.

If left to its own devices, the trend I see for Israel on the horizon is its increasing mental and economic isolation. Here I am simply echoing a general sense that everyone has. Certainly at the university it is palpable. It’s much more problematic to collaborate with foreign universities than it used to be. I suspect this is only the beginning of what will be an irresistible process. There is a deep crisis of trust in Israeli institutions. Many secular people, members of the traditional elite, have no faith whatsoever in their political leadership and institutions and are leaving Israel.

KHOURY: It’s the same in Palestine.

ILLOUZ: Of course. And I think what you said is absolutely relevant.

MARGALIT: I mean, some are leaving. But it’s not a big trend, is it? I don’t see it.

ILLOUZ: I think it is a significant trend. The university feels it very much. We have great difficulties bringing back the outstanding students who went to do their Ph.D.’s outside the country.

MARGALIT: I deal with these centers of excellence and . . .

DAYAN: I will say that in insignificant circles it’s a significant trend.

ILLOUZ: In insignificant circles? I am not surprised that Dani Dayan thinks Israeli academia to be an insignificant circle. It takes time until we can properly measure the percentage of migration and the characteristics of immigrants in the last years. But just so we understand the current atmosphere, a comprehensive survey published in Haaretz revealed that nearly 40 percent of Israelis think about emigration. This is a striking number.

AVISHAI: Let’s table that for a second. We should come back to the question of whether the kinds of political changes you anticipate, Erel, are conceivable without the threat of global isolation that Eva is referring to. But I want to give — do you want to say one last sentence?

ILLOUZ: I just wanted to add another observation, about the trends I see on the horizon. I see at work a process of what I would call the dis-enclavation of Israeli Arabs. Arab towns are exploding because they have no land or building permits, and there is no way for the tiny physical space left by Israeli authorities to fit the demographic growth. This will lead to two trends: spillover of Arabs into Jewish towns and urban centers, and greater racism. Israeli society was relatively free of noxious racism for as long as Arabs were kept in faraway enclaves. But those enclaves will not work anymore. We are going to see greater integration, not by ideology and not by principle, just by the force of demography, and this will in turn create racist backlashes inside Israeli society.

AVISHAI: Since Eva mentioned the trends among Palestinians who are Israeli citizens, I want to give Forsan a chance to jump in here.

FORSAN HUSSEIN: I want to go back to Bassim’s first point, which is that we don’t know each other. This is the heart of the issue. I come from a small village up north, Sha’ab. It was a major village before 1948. Today, Sha’ab is a place of internal refugees. As an Israeli Arab, a Palestinian Israeli — whatever you want to call me — I grew up on the most extreme Palestinian narrative, was fed every type of stereotype you can get. When I was nine and ten years old, it was the height of the First Intifada. And as an Arab who does not speak Hebrew, from that early age it was easier for us to watch Syrian and Jordanian TV. And, of course, the Arab media at the time portrayed the worst images of Israel. Realistically speaking, these were ugly images — of the Intifada, of the soldiers. It was only by chance that when I was ten years old I met a Jewish person. I tended my family’s goats, and one of them wandered into the neighboring village, a Jewish village. It was such a shock that it dismantled all the stereotypes that I had. I helped create the first organization in Israel that brings Arabs and Jews together.

I’m thirty-six years old today. Twenty-six years have passed. That’s an entire generation. Today, if you look at the polls, 58 percent of young Jewish Israeli high school students believe that Israeli Arabs should be encouraged to emigrate. So I’m not that optimistic about greater integration. I was blessed to have left my village and gone to the States. I spent thirteen years of my life there. And I learned one very important thing about the American model, which is: strength comes from diversity. But in Israel diversity is a source of major suspicion. We’re not comfortable with diversity.

AVISHAI: Khalil, you’re the numbers man. Are we in fact pulling ourselves further apart?

KHALIL SHIKAKI: That’s a good question. There is no doubt that on the issue of what Palestinians believe — and I will talk about Palestinians; there are enough Israelis here to talk about what Israelis believe — in terms of ideas and in terms of loyalties, things have been in a little turmoil. I lived in this city in the 1960s and early ’70s, right after ’67. Because of that openness that Danny describes, I was able to leave Rafah, where I was born, to live in Jerusalem and go to school here. In those days, traditional values were much more important than national identity. Loyalty to Jordan and continued belief in links to Jordan were still very strong. The idea of a two-state solution was universally rejected by Palestinians. The idea was basically considered treason. You’re abandoning the goal of liberating all of Palestine.

After the ’73 war, however, the Palestinians felt that the Arabs were abandoning them. That’s when the idea of a two-state solution gained significant momentum. There were no Islamists during that period. By the mid-1970s, the pro-Jordanian elements were being gradually kicked out of the West Bank, politically, in part because Israel opened its labor market. Going to work in Israel made a lot of Palestinians develop different perceptions — about Israel, about Jordan, but most importantly about their own identity. They no longer viewed themselves as connected to Jordan. The Palestinian national movement became essentially the master of both the West Bank and Gaza by the second half of the 1970s.

Another development started to take place at that time, which was that West Bankers and Gazans were developing their own political views that were not necessarily compatible with those of the PLO. And the eruption of the First Intifada was when things inside the West Bank and Gaza started to take the lead in Palestinian affairs, which accelerated the idea that a two-state solution was the way to go. But it also introduced the Islamists. So the First Intifada essentially introduced the two conflicting ideas that have fought for Palestinian loyalty since then — a two-state solution emerging among the nationalists, and Islamists rising to threaten that.

While the Islamists were beginning to gather their strength, the nationalists were conspiring to sign the Oslo Accords. The signing of Oslo essentially preempted the Islamists, and for almost a decade the nationalists reigned supreme among Palestinians. The peace process and the two-state solution were the dominant ideas among Palestinians. Although there was some violence at that time, Palestinians who supported the two-state solution and the peace process rejected violence completely and believed in diplomacy. In terms of Palestinian public opinion, and for the Palestinian national movement, this was the golden age. This was the heyday for nationalists, for the two-state solution, and for diplomacy.

The Second Intifada changed all of that. What the Islamists could not do in the First Intifada they did in the Second Intifada. They became number one in terms of public support. They won the 2006 elections. This did not necessarily mean the end of the two-state solution. There’s no doubt that we see less support for the two-state solution, but most Palestinians continue to support it. The nationalists continue to be the largest political force, though not as big as they were before the Second Intifada. Islamists have the support of about one third of the Palestinians. Of this one third, the overwhelming majority are people who share Hamas’s values, which is to say this support is solid and not a temporary kind of support. The rest support it because of other reasons. One reason is the belief that the nationalists have failed in their most vital goal, which is to end the occupation and build a Palestinian state through diplomacy.

Assuming that diplomacy will not bring about a two-state solution, the trend will most likely take two forms. Either the Islamists will win the day, or a new development among the nationalists will emerge. The new development I’m talking about is something we observe among the younger half of the adult population — people between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four — and that is the solid support they have for a one-state solution.

If the generation currently in favor of a one-state solution continues to grow — that is to say they do not abandon the one-state solution as they get older — then in ten to twenty years, they will be the overwhelming majority of the population. We’re moving away from national identity; we’re moving away from a two-state solution; we’re embracing more universal values or else Islamist values. That is where the competition is likely to be in the future.

PART TWO: “WE ARE NOT A FORT. WE ARE A HUB”

AVISHAI: We’ve done a very good job of laying out terms here, saying where things stand now. But what, more specifically, are the possibilities for the future?

RUBINSTEIN: Since I started covering the territories, I have believed in the Green Line, in the pre-’67 borders. Because you have to start somewhere. The ’67 borders should be the only starting point for any kind of dialogue. And why is that? The ’67 border was the only border that was recognized. The State of Israel had global recognition with the ’67 borders. For me, there is a sort of . . . I cannot say “sacred.” There’s no holiness in any border, but from a political point of view, this is the border. This is Israel’s border. So in the future, if you need to uproot settlers, like Dani Dayan, well, that hurts me. But Bassim’s family, and Khalil’s family, they were uprooted. We displaced almost 1 million Palestinians in ’48. We are now talking about a few hundred thousand settlers. It’s not a big issue.

I think everyone knows all that. The real issue is the economy. In Israel, annual per capita income is $35,000. In Gaza, it’s $1,000. It’s a bit better in the West Bank — $2,500 or $3,000. But that’s a huge gap. You cannot build anything with that. Dani, you put the blame on Gaza. They made the wrong decisions. But a decision was made by Ariel Sharon not to develop Gaza. They have a gas field in Gaza, but Israel decided, “No, we don’t want to buy gas from the Palestinians. We should buy from the Egyptians.” If Israel won’t buy the gas, the Palestinians don’t have any other customer. Why don’t we give them an opportunity to work in Israel, to develop Gaza?

KHOURY: I am well acquainted with those gas negotiations. Initial reports indicated that we have 1.4 trillion cubic feet of gas in Gaza — an estimated value of $4 billion. Israel’s idea was, “Yes, you can have the rights and you can exploit the gas in Gaza. Under one condition: you give it to us and we will not pay you in cash. We will pay you in goods and services.” This is the hostage taker’s mentality, the mentality of the occupier. According to Israeli and Palestinian statistics, in the wake of Oslo an average Israeli was earning twelve times as much as an average Palestinian. After six years of peace, in 1999, you would have expected that this disparity had shrunk, but in reality it rose.

Israelis have so far managed to close their eyes to what they call the “benign occupation.” Well, there’s nothing benign about an occupation. You know, the first thing that came to my mind when I read Dani’s article in the New York Times was, “It’s a farce that you can have a benign occupation.” What is happening, and you Israelis have to face it, is apartheid.

I am a refugee. My family came from Mujaydil. For those of you who don’t know, Mujaydil is a village to the west of Nazareth on the way to Haifa. We were forced to leave in 1948. The only thing remaining from the village is the church my great-grandfather built. It’s no secret we lost a lot in ’48 as the largest landowners in the village. I have decided that I want to leave that all behind. To me, the Green Line is a red line. If you really want to open the Green Line and the two-state border for negotiations because you have some affinity somewhere in the West Bank, then people like me will start pushing to move the borders only five kilometers to the north, and I can get my ancestral land back. And that, in a sense, opens a Pandora’s box.

Photographs of bomb shelters in Israel, by Adam Reynolds. By law, all Israelis are required to have access to a bomb shelter, which are at times repurposed for other uses. Clockwise from top left: “Flamenco dance studio/public bomb shelter, Jerusalem”; “Pub/bomb shelter, Kibbutz Kfar Aza”; “Conference room/bomb shelter at the Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem”; and “Science classroom in a secondary school designed to withstand rocket attacks, Sderot.”

Respecting borders is crucial. The colonial infrastructure and the wall make it impossible to have a contiguous Palestinian state. In this regard, I don’t believe that walls build peace or security. However, if Israel believes it needs to make a wall eight meters high between us and them, let them have it eighty meters high. Under one condition: it has to be on the international border. What is missing from this whole discussion is that on November 29, 2012, an overwhelming majority of the world, a two-thirds majority in the United Nations, voted yes to a Palestinian state on the 1967 borders. Israel and its colonists can claim whatever they want, but according to international law, this is occupied Palestinian territory. Not territories, it’s one territory occupied by Israel. By the way, for those of you who don’t know, the territory internationally recognized as the State of Palestine constitutes 22 percent of historic Palestine. We have forgiven you for 78 percent, for crying out loud. You’re telling us to compromise on the 22 percent?

AVISHAI: Let’s say we have to have a border. What is that really going to have to look like? Do we actually have to have a border in order to have two distinct national groups who are going to live in their own communities? Is there not more to be said about what you think is going to be plausible given the forces that we’ve identified now on the ground? Go ahead, Dani.

DAYAN: Well, the ideas that were presented by Bassim and Danny, whether they’re nice or not, the fact is that they are unimplementable. Look, the partition — once we called it partition; now we call it the two-state formula — the partition has been the only game in town for the past twenty years, but I dare to say that it has been the only game for the past seventy-seven years, since Lord Peel came here in a mission sent by King George VI in 1937. And it doesn’t work.

Why doesn’t it work? Because one side accepted it and the other started a war in order to prevent it. And that will almost be my last word about the past. The other word that I must say about the past is that the Jordanian army that invaded Israel in 1967 shattered whatever sanctity existed. The Green Line was shattered by aggression against Israel, by an attempt to take it all by force.

The tragic reality is that the conflict now does not have a solution. I want to be more accurate: It does not have a solution that can be agreed on by both sides. A negotiated agreement is a utopia. The positions of mainstream Israelis and mainstream Palestinians are worlds apart on almost every core issue. The big challenge — for all of us, Israelis and Palestinians — is whether we are able to separate the national from the human. If we are able to differentiate the national from the human, we can make tremendous advances.

MARGALIT: Look, let me tell you something. Despair and the pessimistic approach are not in the cards. I’ve joined the political life and I see the dynamics. The Israeli Knesset has a majority for a two-state solution, a clear majority.

RUBINSTEIN: And according to Khalil, also among the Palestinians there’s a majority?

SHIKAKI: Yes. For at least a decade, if not more, majorities in both societies have been willing to accept the compromise that one could describe as a two-state solution. But the demands of the mainstream Palestinian national movement are not compatible with the right-wing mind-set in Israel. If there is a right-wing Israeli government, then there’s absolutely no way that we can make the Palestinian positions compatible with that. Since Netanyahu was elected, since the right-wing coalition has been put in place, it’s just not doable.

MARGALIT: I agree. It’s a question of leadership. There’s overwhelming support on the left, center, and even on the moderate right in Israeli society for a two-state solution with land swaps. The settlers, there are — what is it?

DAYAN: 375,000, not including eastern Jerusalem.

MARGALIT: How many of them are in the blocks? 300,000?

RUBINSTEIN: 80 percent of them.

MARGALIT: So you see, most of the settlers are within the big blocks, which can be traded in these land swaps. I believe that most of the settlers outside the blocks will agree to economic value for their homes. There’s going to be a big group that won’t agree to this, and we need to have a debate within our own people. And the issue is this: Israel is waiting for the kind of leadership, just like the Palestinians are waiting for integrated leadership, that will —

DAYAN: It’s a fantasy.

MARGALIT: Maybe, maybe . . . You know, that’s what they told Herzl when he dreamed of a Jewish state. That’s what they told the movement’s leader, Ben-Gurion, when there were only 50,000 of us here. They told us we were fooling ourselves, but we succeeded. We are not a fort. We are a hub. We can find a solution between us and the Palestinians. The solution would be —

DAYAN: All the empirical proof is against your thesis, and you’re talking with such self-confidence. Seventy-five years of history contradicts what you just said. The twenty years since Oslo contradict all you are saying. Just a bit of humility after failing, and failing, and failing.

MARGALIT: I think you need some humility! The movement that established this country was about building what others said was impossible.

AVISHAI: I think we understand each other’s positions by now. We know each other’s positions. I want to come back to what you meant by a “hub” rather than a “fortress” because I think that at least gives us a gesture toward some kind of future.

And I want to ask a question, which is: let’s assume you could have some kind of political accommodation, how do you imagine it could succeed? We don’t have a million people on each side fighting over hilltops to see who can be farming in the valleys. We’ve got 12 million people in 10,000 square miles, and we have a largely urban population. And we keep talking about this fight as if we’re back in ’48. I want to understand how we can actually think about the future, not simply in the categories that brought us to this standoff. I thought in Dani’s article, he was aiming in that direction. Bassim, you said it was a farce.

KHOURY: No, the farce is believing that we have a benign occupation. You cannot have a benign occupation. Occupation is a malignant cancer, and as with all malignancies it must be removed. That’s what I meant.

AVISHAI: So we go back to the end of the occupation through the reimposition of some kind of border through a political accommodation, which at least some people around this table believe is possible.

SHIKAKI: And I would like to say something about political accommodation and link it to what I said earlier about the support among the youth for the one-state solution. That isn’t something that the youth believe the Israelis will give them. They believe once the one-state reality is consolidated, and Palestinians recognize that this is a reality that cannot be changed through diplomacy and negotiation, that they will then dismantle the Palestinian Authority and begin to fight a South African style of resistance — fighting for equal rights, one man, one vote.

ILLOUZ: These Palestinian youth understood something very powerful. If there is a framework in which they can make practical claims like “one man, one vote,” then this is a way of solving the problem that is non-ideological, so to speak. It doesn’t go through the politicians. The politicians have failed. Ethnic and religious and nationalist ideologies — which make Israeli and Palestinian societies mirror images of each other — have become very powerful, but they have also failed to provide a sustainable and convincing means of coexistence. The other mechanism, which I think Erel was referring to earlier, is something on the order of: “Let’s create facts on the ground. Let’s have Israeli Arabs mediate this process and play a much bigger and much more formal role than has been given to them.” And then you change the terms of the identity and the negotiation.

MARGALIT: That’s exactly what’s happening. In Israel, we used to speak about the “Israeli Arab problem.” But today, there’s an overwhelming opportunity. There are so many young, dynamic, interesting, educated, well-meaning, constructive Israeli Arabs in the north and the center of Israel that it’s overwhelming. In other words, they’re getting into the new economy.

HUSSEIN: I agree with you, Erel. And I’ve always seen the Palestinian Israeli community, the Israeli Arabs, if you will, as that perfect bridge. But this is where I have a problem with our country, which is that we have become a hypocritical country, a country of hypocritical policies.

MARGALIT: What do you mean?

HUSSEIN: What I mean is that I personally am — and the entire Israeli Arab population is — sick and tired of being in no-man’s-land, of being seen as Grade B citizens, a constant security threat to our very own country. I see discrimination all over the place, even when I visit my family up north and walk into my village. I sense the density of the Arab population, and I look up and see the moshavim surrounding Sha’ab. I see Jewish communities spreading disproportionately, expanding into Arab villages’ land. I see discrimination in budget allocation in every area. From a psychological perspective, Israel’s discrimination toward its Arab citizens is very much like its occupation of the Palestinian people. When you discriminate blindly, you cannot trust. And if you can’t trust us, we can never reap the benefits of living and working together. The right moral and even Jewish thing to do is to reach out to the Arab population and engage them so that they become an asset to the country, not a perceived threat. So the hypocrisy comes from Jewish leaders not living up to their own Jewish values.

But Israel is also missing a huge opportunity — economically, socially, culturally, and even politically — by isolating the Arab population. Israeli Arabs can be the perfect bridge between Israel and the rest of the Arab world, but unfortunately Israeli Jewish policy and policymakers must have a paradigm shift toward the Arab population. Imagine if a million and a half Israelis who are not Jewish could call themselves Israelis with pride. Imagine what a change such a minority could bring to the image of Israel in other Arab countries and populations throughout the Middle East.

AVISHAI: I want to turn to Bassim and Khalil. I want to ask you whether you believe that, in your own national communities — that is to say the community that still believes in a national solution as opposed to the Islamists that you were describing — there is sufficient honesty about the need to work with Israel, about the importance of proximity to Israel and Israel’s intellectual capital in order to succeed? Or you can turn it around. Can you imagine a Palestinian state succeeding in the absence of the kind of partnerships that we’ve been describing?

KHOURY: I thought the purpose of today’s meeting was to think about the future. So without treading too much into the past, let’s briefly consider the year 1987, when the First Intifada started. Statistics indicate that it was the best time for Palestinians economically. The Intifada did not come about because of economic issues. It was a cry for a national identity.

Up until the Second Intifada, we had a budget surplus in Palestine. There is so much potential in Palestine, given the chance to break free of Israeli control. Through the wall and the colonial infrastructure, Israel imposes a complete matrix of control on Palestine. Whether it is on movement, on water, on electricity, telephones, you name it — with literally a click of a button, Israel controls what happens in occupied Palestine. I believe that when we get our freedom, this country has huge potential. There are so many interesting projects that we can develop, not just gas. Tourism is one. Small agribusiness is another. Of course being close to a strong economy like Israel’s, if there is the goodwill of working together, will make our life easier. But to be honest, we have to divorce before we can think of the good things that might have been in the relationship when we were together.

SHIKAKI: In a context of progress at the political level, Palestinians support a significant amount of economic and social integration with Israel, with open borders.

But the idea that you can improve things economically without ending the occupation is simply not viable. Palestinians know that everything in Israel is dependent on security, and that as long as the occupation is here, there will be resistance. There will be violence. The Israeli reaction is to destroy the economy as a punishment for Palestinians. So the idea that you can use economics alone is unrealistic.

But Palestinians fully support the idea of some form of future cooperation as a confederation of some sort or just one economic union between two states. Here is another surprising thing about how Palestinians perceive Israel: When we ask people to tell us how they perceive Israeli democracy versus, say, American, Jordanian, or Palestinian, Israel’s democracy comes out on top. Despite the discrimination against Israeli Arabs, the Palestinians still consider Israel’s democracy to be the best democracy in the world. And they want a democracy for themselves just like that.

HUSSEIN: Okay, so maybe this is the beginning of thinking outside the box and realizing, “Hey, there are some things that we could do today.” So if we all agree that in the future there will be peace, and part of the issue now is maybe the right-wing Israeli government, maybe the weak Palestinian leadership — and it is an issue of leadership — then maybe what we’re not doing today is the right thing for the future generation.

If we continue to be stuck in this leadership obstacle, maybe we start moving things on the ground. Maybe Israel should decide, “You know what? Okay, this is the time for Israeli Arab school systems to also learn about their own history,” because it is important not just to learn about the Jewish narrative. Maybe it is the time to start thinking in the Palestinian Ministry of Education, or —

SHIKAKI: You cannot do this simultaneously with the Israeli occupation continuing the way it is today. For most Palestinians, the Israeli occupation is about destruction. It’s about destroying their livelihood, destroying their aspiration for independence, stealing their land and water, demolishing their homes, preventing their free movement. Unless you give them hope that there is a political solution, these things that you’re talking about would be meaningless.

DAYAN: I am quite depressed, I must say, by the discussion. I am depressed because in the choice between the most important but unattainable and the important but attainable, we choose to talk about the most important but completely unattainable. And that’s a tragedy.

MARGALIT: You should add, “in my view.”

DAYAN: Everything everyone says here is his view. And that’s a tragedy because we will keep being engaged, in the coming decade, in futile processes instead of processes that are less important, less glorious, less heroic, do not resolve the conflict, but can change the lives of people.

KHOURY: The farce of a benign occupation.

DAYAN: Let me ask you something, Bassim. The option for what you call benign occupation — I reject the term, of course, but let’s use it for a second. Would you rather have an occupation that is not benign? What is the alternative?

KHOURY: Pack and leave. Dismantle your colonial infrastructure and go back a few miles west, to your country. Live within a recognized and secure Israel.

DAYAN: We will not pack and leave. Certainly not without peace. So this is exactly the tragedy, that you are replacing reality with wishful thinking. The reality is that the negotiated agreement is not achievable in the foreseeable future.

MARGALIT: On what basis?

DAYAN: My analysis of the current position of the mainstream Palestinians and of the mainstream Israelis. Okay? Now, given that, Forsan has talked about the hypocrisy of the Israeli society. And I agree with you. In Israeli society, there is a lot of hypocrisy regarding the Israeli Arabs for sure — not only on that. But let’s talk for a second also about other types of hypocrisy that we saw here at this table. For instance, in my plan I suggested opening Hebron for every human being, without any barrier. And Bassim calls it a farce.

KHOURY: Dismantling the cages you force Palestine to live in is a step in the right direction. I’m not telling you not to do it.

DAYAN: I’m quoting you.

KHOURY: Do it. Open the gates and dismantle the wall. I’d be very happy if you did. But to do that while retaining a cancerous occupation and believing it is a long-term solution is a farce!

DAYAN: I don’t understand what’s farcical about it. I suggested very explicitly to live normally under those very abnormal conditions, as normally as possible. I’m suggesting freedom of movement. I am suggesting rehabilitating . . .

SHIKAKI: What will you do when the next bomb goes off?

DAYAN: That’s a great question. If my plan is accepted in Israel, then the Palestinians will be again confronted with a moral and political dilemma. A dilemma — a dilemma is between two hard choices, by the way. It’s not between a good one and a bad one. It’s between two hard choices. Otherwise, it’s not a dilemma. The dilemma is whether to live until a resolution of the conflict is reached, in better conditions without limitations of movement.

SHIKAKI: I’m asking you what you will do when the violence comes. Because if there’s an occupation, there will eventually be violence.

DAYAN: That depends on your choice. If your choice is a better life, if your choice is a better quality of life, if your choice is coexistence, a peaceful non-reconciliation, then we will go along with that. If your choice is to resume homicide bombings — and homicide bombers can thrive only if they have the support of the people and the establishment — then you will again pay a price.

PART THREE: “PALESTINE IS NOT JORDAN”

AVISHAI: Just a moment. Basically what you’re saying is: Don’t look at me and say that I am precluding the possibility of reconciliation. It’s just that mainstream —

DAYAN: Never underestimate national sentiment.

AVISHAI: But if you just insist there’s no possibility of reconciliation, you don’t have to win an ideological debate. That goes for those on both sides who don’t want reconciliation. You don’t have to make the case for your vision. You just have to sow cynicism.

DAYAN: My plan does not preclude any political solution to the conflict. You can adhere to it as a staunch two-state supporter or an opponent of the two-state formula. It’s a way to live until peace arrives.

AVISHAI: But if we open up freedom of movement, that’s a gesture toward some vision of the future, right? This is what I hear you implying, that at some point in the future there will be some basis for an accommodation.

DAYAN: Contrary to what you say, I do have an ideology. But I do not superimpose my ideology on reality.

KHOURY: What is it? What is your ideology?

MARGALIT: You said these are the circumstances until peace prevails. What does peace look like to you? What conditions do you see?

DAYAN: I think that as Shimon Peres suggested in the ’70s, before he converted to the Oslo religion, it will be based on two precepts: a Jordanian option as opposed to a Palestinian option, and a functional compromise as opposed to a territorial compromise.

One implementation of that could be two states with the Jordan River as their limit. Nevertheless, that Arab state east of the Jordan will have authority — real authority, real governance — over the Palestinians on the other side of the river. I call it functional enclaves. And that will achieve three principles. Security will be in Israeli hands from the river to the Mediterranean, which is a precondition for any situation to be sustainable. Israel will stay as a democratic and Jewish state. And this is the third one: Every individual will be a full-fledged citizen of the state that governs his life.

KHOURY: This whole concept of a Jordanian option is a pipe dream. It didn’t work in the ’60s and ’70s when there were proponents of the Jordanian option among Palestinians, as Dr. Shikaki described. It will definitely not work now.

I was born in Jordan, I spent most of my life in Jordan, most of my family lives in Jordan, but I was never and I will never be a Jordanian. Why? Because just as there are dynamics, maybe not as much in the open, that exist against integration with Israel in Palestine, there are dynamics against integration with Jordan. Dr. Shikaki described how the Jordanian option lost gradually to the national option for Palestine. It is important to remark that for Jordanians — who are now a minority in their own country due to the influx of refugees — Palestine is not Jordan. We thank the Jordanians for sixty-six years of hospitality, but we will never take their land as ours. My home is Palestine.

MARGALIT: But you agree that economic cooperation, economic joint ventures, can give a flavor of how cooperation is attainable. It’s happening now. And this is something that I don’t understand with some of my colleagues, you know, the business colleagues, in the Palestinian Authority.

KHOURY: I presume you mean in Palestine?

MARGALIT: Yes, in the — well, it’s not Palestine yet.

KHOURY: It is. Why can’t Israel accept that?

MARGALIT: It’s not.

KHOURY: It’s a state under occupation according to international law.

Flares illuminating the sky following an Israeli air strike over Gaza City early on July 3, 2014 © Ali Jadallah/APA Images/ZUMA Wire

MARGALIT: Okay. You want it to be Palestine, and I support you. Maybe some people look at economic peace as something cynical because they don’t want a political agreement. But most of the people who are involved in joint ventures are interested in a political agreement. And they’re looking to culture, education, and the economy to be pillars of trust. They don’t want cynicism to prevail over the mainstream. The mainstreams of Palestinian society and Israeli society need to be building bridges now. Great things are built one step at a time.

SHIKAKI: I would like to disagree with you. I think it’s a good idea in theory, just like Dani’s ideas are good in theory. Israel can go ahead and implement those unilaterally and I think this will significantly improve the mood in the West Bank and will contribute to better relations between Israelis and Palestinians.

But the idea that you can actually do that for a prolonged period of time I believe is nonsense. Palestinians whose land is confiscated, where settlements are built — they will rise. You simply cannot convince them that nonviolence is the way to go. They will resist. And there will be violence. It’s just like what we saw in the past few days. It might be six months before we see something, it might be a year, but there will be violence. There might not even be violence. Palestinians might actually resort to diplomatic moves in the international community. And Israel will feel that the Palestinians are not behaving and in order to convince the Palestinians to behave, Israel will impose sanctions and punish them.

MARGALIT: Going to the U.N. would be counterproductive.

SHIKAKI: Yeah, but this is the point: You don’t like what we do, we don’t like what you do, because of occupation. Now you want to ignore all of that. The idea that you can improve economic conditions or improve living conditions for Palestinians and expect them to say, “Yes, sir, we’re not going to do anything to harm the interests of the state of Israel,” is absolute lunacy. The Palestinians will resist in one way or the other, and you will punish them. And you will punish them severely, depending on what exactly they do. And the casualty, the first casualty, will be Palestinian freedom of movement. The Palestinian economy will be destroyed. That’s what Israel does all the time. Israel uses freedom of movement, economic progress, as leverage against the Palestinians. This gives you a menu where you can hurt us best — and you can hurt us economically, you can hurt us by putting up checkpoints — every time we do something you don’t like.

AVISHAI: Let’s say we can easily agree that you can’t have economic peace without a political track and you can’t have a political track without economic initiatives to provide an image of cooperation between the two sides.

MARGALIT: That’s what leadership is about, and it’s lacking on both sides at this time. But it’s a political battle. It’s a political battle within our societies. It’s a political battle about the nature of our own states.

AVISHAI: I just want to come back to the question of federal arrangements of some kind because that was a long-term vision for three people coming at it with different configurations. There seems to be a kind of implicit long-term vision here, which we keep circling back to and not acknowledging. Now, do you buy that?

DAYAN: No. What I buy as an ultimate solution is what I already suggested. But I want to be more explicit on a point that is related but somewhat different: there was an implicit assumption around the table that — there was a discussion whether a two-state formula is attainable. But there was an implicit assumption that if attained it brings peace and stability. I beg to differ with that. The two-state formula is not only unattainable; it will also not bring peace. It will be, as a matter of fact, the prelude to another armed confrontation. I have no doubt at all about that. And the reason for that is, as I said earlier, one should never underestimate national sentiment. The thought that an arbitrary line — and every line will be arbitrary — that is delineated between Jordan and the Mediterranean will be stronger than the mutual national sentiments in my view is completely out of touch with reality.

If you ask me, very shortly — I will say it in two sentences — what is my scenario if the Palestinian state is established in Judea and Samaria. As Bassim said, there’s going to be a flow of refugees, some of them forcibly moved there by their host countries.

KHOURY: Coming back home.

DAYAN: Okay. Coming back home. But that will be a hotbed of extremism.

KHOURY: Let us deal with that, and you deal with your extremists.

DAYAN: No, it’s not for you to do that because the —

KHOURY: Yes, it is.

DAYAN: Just let me finish the sentence. The tensions that it will create will move westward, into Israel. And if you ask me what will be the final outcome of the establishment of a Palestinian state, it will be a new armed conflict in which the best scenario — not the worst — is that Israel will manage to recapture Judea and Samaria. And we will find there an additional half a million Palestinians, and we will start the whole loop again.

KHOURY: Let me remind you one more time: There is already a Palestinian state. This is a state that was recognized by the overwhelming majority of the countries of the world. I would like to return to something Dr. Shikaki mentioned, which is that Palestinians might go back to the U.N. We also have a chance to go to the International Criminal Court about war crimes committed by colonists and occupational forces, whether ethnic cleansing, ill treatment of prisoners, water issues, or economic issues.

This is what John Kerry referred to as Palestine’s nuclear option. I hope we will not be forced to go that way. However, I can tell you bluntly if it continues like this we’re going to. And to be honest, I would be very happy if the judge between us were international law, not who has more men, not who has more guns. We’ve been trying to resolve this between us for so long, through honest or dishonest brokers, whatever you want to call them, through countless efforts. We have discovered what we can do under international law, and we will push to attain it. I hope we will do it peacefully. I am confident we will do it peacefully. We don’t want to fight. Let the ICC decide. Let them be the judge. If two people are fighting over a car accident, they go to a judge.

PART FOUR: “THE KERRY INTIFADA”

AVISHAI: Since you mentioned John Kerry, this seems like a natural segue into the American role in all this. How do you all view that role? Is it useful? Is it fake? Do you expect the United States to do anything constructive, or have you given up hope on a constructive American engagement?

RUBINSTEIN: For many, many years my dream was that the American administration would force us — both Palestinians and Israelis — into a two-state solution. It’s not only me. All the Israeli left wing and moderates, their dream was that Americans would come and force it. It didn’t happen for almost fifty years.

When I saw Secretary Kerry trying to do it, I was quite pessimistic at the beginning because I understand that it’s not realistic anymore. The two-state solution — here I agree with Dani Dayan — it’s not relevant anymore. The American administration, after those fifty years of trying to impose this, should see that it’s not valid anymore. The Americans should give up on that and say, “No more two-state solution.”

MARGALIT: But there should be an American role. Like anyone who is brokering negotiations, you can do a good job and you can do a mediocre job. A lot of it has to do with the level of expectations that you set. There were many mistakes made in the Middle East by the current administration, here in Israel and elsewhere, expectations that solutions were in the offing. If you’re creating an expectation that in nine months we will solve it all, then if you’re solving it in twelve or twenty-four months you’ve failed. So I think that Kerry’s approach was very admirable but couldn’t have succeeded without the full backing of the administration, and with a time frame that was nearly impossible.

KHOURY: The question is: Who is in control? Are U.S. interests dictating to Israel or the opposite? Many here believe that U.S. actions are determined by what the Jewish lobby in the U.S. wants. I believe it’s the exact opposite. I believe — with all due respect to you guys — Israel is a base for American interests in the Middle East. It’s a huge aircraft carrier.

MARGALIT: If you want to have a conversation based on mutual respect, don’t call us an aircraft carrier.

KHOURY: I am not calling you anything. I’m describing how big powers operate.

MARGALIT: You know, this is the land of my fathers, of my Bible, of my heritage. That’s why I’m here. If you call me an aircraft carrier, I’m offended.

KHOURY: I’m speaking about what I perceive to be American policies. The Americans view Israel as an aircraft carrier. They view the whole Middle East through the prism of U.S. interest. Of course they allow leeway here and there. But if there’s a crossing of a red line by any of us, the United States will know how to put us in our place.

And so to be honest, I don’t think Kerry was doing something just because he is an honorable man. I think he genuinely believes that it is in American national interest to do something about this conflict. It’s not because he wants to be remembered in history. Of course, everybody has his own personal ambitions. But had it not been in America’s national interest, it would not have happened.

When Kerry gave nine months, it was in the genuine belief that we could achieve something in nine months. As somebody who was working with the Kerry team, I can tell you they meant well. I mean, he used a lot of his personal political capital when he brought all those consultants from McKinsey and whatever to come in their private jets — they were trying to think outside the box, to see if they could do something different.

ILLOUZ: When one sees the massive investment of Israel in the military and the fact that this society thinks of itself and its politics primarily in military terms, Bassim’s metaphor of Israel as an aircraft carrier seems quite apt.

DAYAN: I was in Washington in June 2013, when Secretary Kerry tried to jump-start the negotiations. I had a breakfast with the chairperson of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the House, Ed Royce, and with Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, the chairperson of the Subcommittee on the Middle East. And I told them Kerry would manage to jump-start the negotiations — he has to press a few buttons here, a few buttons there, and that’s doable — but that failure is inevitable, and that will be an additional blow to the national interest of the United States, to the prestige of American diplomacy. They will take notice in Moscow, in Pyongyang, in Caracas, in Tehran, in Damascus, in all the places where America is not a favorite.

The thing that amazes me most about American diplomacy during the last year is how immature it seems to be, how unprofessional. I would even say, contrary to what Bassim said, driven by personal interests and personal inclinations. It is inconceivable for a secretary of state of the United States of America to enter a process like this, in which — let’s use an understatement — there were fair chances of failure, without an exit strategy, without a contingency plan in place in case it really fails. And that’s exactly what happened.

You know, Secretary Kerry during this past year developed an expertise in threatening Israel — I say this as an objective commentator, not as an interested party. It was the boycott issue in Munich, and finally the A-word [apartheid] in that unfortunate conversation in Washington. If a Third Intifada arises, it should be named after John Kerry.

AVISHAI: Khalil?

SHIKAKI: I don’t think Palestinian-Israeli peacemaking will succeed without a strong American role. But that role, I believe, has almost zero chance of succeeding if the gaps between the two sides are as wide as they are today. If the gap was the gap between Olmert and Abbas, then the U.S. role would be critical and most likely successful. But given the distance between a right-wing government in Israel and the Palestinian side, I cannot see a way for the United States to succeed without having to use a great deal of leverage against Israel — which I think is simply not realistic. If the gaps can be narrowed somehow due to domestic changes in Israel and Palestine, then I think the United States can play a very constructive role. To succeed, the United States would have to do two things. They would have to present their own ideas to bridge the gaps. The two sides might not necessarily like it, but I think this is something that the two sides would ultimately agree to, even if they don’t like it.

Second, the United States will have to use leverage. The United States can use leverage any time it wants. So far, it has really avoided using leverage, particularly against the Israelis, in the way, for example, that Kissinger did in the ’70s or Jim Baker did in the ’90s. This administration and the previous one have avoided a situation where the United States is seen as pressuring Israel. But I just don’t see any way for progress to take place without the United States putting pressure on the two sides. On the Palestinian side, the easiest way is to withhold money. The United States supports the PA with about half a billion dollars a year. So the United States should say, “No, thank you. We don’t like your policy. There will be no money.” In the case of Israel, I don’t think this is an option. However, I think the United States can say, “We will not interfere in the business of the U.N. if you don’t do what we think is the right thing to do.”

ILLOUZ: As of today, it seems the solution can only be forced, either by greater powers than the actors in the conflict — by a coalition of the United States and Europe, for example — or by the populations of each country, the citizens who will just do what citizens do best: change the terms of a politics that has failed them. Israeli and Palestinian citizens have the same interests, and perhaps the future lies in building up networks and frameworks of solidarity between them, so to speak, above the heads of political leaders and institutions.

HUSSEIN: You can’t talk about an American involvement when you discuss only the administration. There is a huge role for American Jews to play in this. You have a vibrant Jewish minority. We have programs like Birthright Israel, which started as a brilliant program to educate Jews around the world about the State of Israel. You know, you come here and you show them the image of Israel that you want to portray. I am deeply involved with Birthright. I share stories with them about my life, about my father’s experience constructing the new wing of the Israeli Knesset in 2004. And guess what? Only last week, I received a phone call from Birthright Israel saying, Please, Mr. Hussein, we love you. You know, our kids from Harvard and Johns Hopkins and whatnot, when they come to Israel they want to listen to you. But could you please do us a favor and censor yourself? I am not someone who comes to bash Israel. God forbid. I love my country, and I want it to be the country that I’m so proud of.

So you come from an educational perspective to prove a point but, you know, the ecosystem is not right because — it goes back to the issue of leadership, whether you’re running a nonprofit, a government, a company. I think the time has come for us to take some responsibility, guys. You know, we screwed it up. And I think, you know, it’s up to us.