Gul Raham, the hymen doctor of Kabul, sat behind a wide desk in an office filled with purple plastic flowers. A bouquet of them drooped over a filing cabinet stuffed with virginity certificates. Two female gynecologists sat quietly on folding chairs. Raham wiped the condensation from his small glasses. “I am a man of science,” he said.

I asked Raham to explain his procedure for determining virginity.

“The hymen is a small curtain,” he began. “There’s a very small hole that allows liquid to come through, like the woman’s period. Sometimes we have a blocked hymen. No hole. We poke a hole in the woman if the fluid needs to come out. It’s very tiny and difficult to reconstruct.”

A woman in Kabul walks up a hill that is covered in homes built since the American invasion, in 2001, when Afghans from outlying provinces began moving to the capital. All photographs © Andrew Quilty/Oculi/Agence VU

Most visits to the forensic center where Raham works involve questions of rape. Women raped by one or several men, or women whose families suspect that their daughters have been raped at domestic-violence shelters. If a man refuses a woman’s hand in marriage, she might accuse him of rape. Or, if a man rapes a woman, she might be forced to marry him, because in Afghanistan sex before marriage is dishonorable. It’s a moral crime, according to the country’s customary codes. If you’re not in a shelter, you might be put in jail. By marrying your rapist, you can avoid jail time. In all cases the hymen must be checked. Sometimes suspicious husbands bring their wives in. “But if her hymen is okay,” Raham said, “then he will have shamed his wife, and the husband might go to jail.”

I was with a twenty-eight-year-old interpreter named Ahmer.* A twist of black hair stuck straight up from his head in the manner of a quail’s forward plume. He turned it nervously with his fingers. It’s rare for men in Afghanistan to talk openly about sex, and rarer still to do so in front of women. (My first interpreter had pretended he didn’t know about hymens and walked away.)

About a month earlier, Ahmer had visited the forensic center and encountered a shamed husband. “He accused his wife of adultery, but the hymen was fine,” he said. “All the workers were taunting him, telling him how he just couldn’t fuck his wife well enough.”

When a woman arrives, the doctors examine her arms and legs first, then move on to the external genitals. Then they go deeper, inside.

“If the doctor is not a professional,” Raham said, “even he can break the hymen by checking for the hymen. In all cases, we have to find out if the hymen has been recently or previously destroyed.”

I asked about the worst-case scenario. It was a young girl, he said, whose vaginal wall tore open during a rape. “Her feces — everything — came out,” one of the female doctors said. “Nonstop.”

“What about sodomy?”

“Yes, then we check assholes,” Raham said. “If it was fine and not used, or itching takes place, or there’s a reddish color on the side.”

Ahmer would not look at me. He covered his face.

“If the hymen is torn, we will take note about the condition under which the virginity was destroyed,” Raham said. “Then give the girl a certificate. Then, stamp and sign.” He gave me some examples of virginity-destroying conditions. Jumping off or falling out of a tree, he said. Raham pointed to the filing cabinet, which contained evidence of all the virgins that had passed through.

I asked about the effects of tampons, but Ahmer didn’t know the word. After a minute of confusion Raham said, “Oh, condoms, you mean? Condoms cause cancer.”

Occasionally, the forensic center did torture checkups. Raham showed me a report stapled to a photo of a ragged man. “Light torture,” he said.

One of the gynecologists asked if I’d like a tour of the building. She showed me the green-lit examination room, with its trays of glinting tools, and then led me to the morgue. “It’s for mutilated women,” she said, “and the unidentified men.”

The morgue was in the basement. We wrapped scarves over our noses and put booties on our feet. The mortician said he was proud of his job; he wanted me to take his photo by the freezer. It had room for nine bodies. He hit the freezer latch and the door opened. A body popped out, quick as a cashier’s tray. It was a drug addict in his thirties. “Ditch body,” the gynecologist said. No mutilated women had come in that day. The mortician raised a finger to indicate that I should wait. He combed the dead man’s beard. He made it nice. Then he nodded. “Ready.”

In the first years after the U.S. invasion, politicians sometimes used the issue of women’s rights to justify the war in Afghanistan. “The brutal oppression of women is a central goal of the terrorists,” Laura Bush declared in a radio address two months after 9/11. “The recovery of Afghanistan must entail a restoration of the rights of Afghan women,” Colin Powell said that same year. “The last time we met in this chamber, the mothers and daughters of Afghanistan were captives in their own homes,” George W. Bush said in his 2002 State of the Union address. But, he boasted, “Today women are free.” In the weeks following the fall of the Taliban, images of unveiled women using products like hair spray and lipstick suggested that this freedom had arrived all at once. If foreign troops withdrew, Bush noted after he left office, “women would suffer again.”

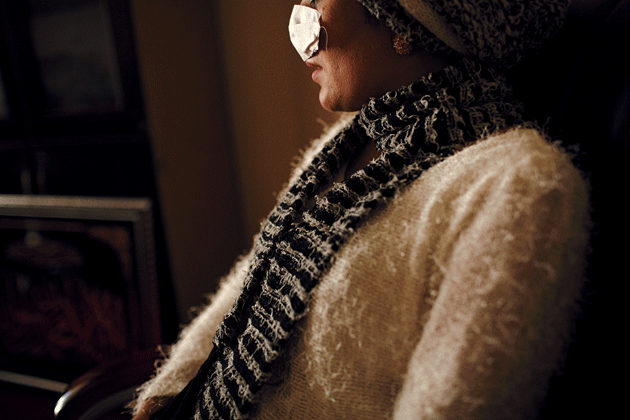

A young woman in a shelter in Kabul that is run by Women for Afghan Women. WAW has shelters in twelve provinces of Afghanistan, the majority of whose residents have escaped abusive marriages, familial rejection, or threats of violence

In November 2013, Hillary Clinton, John Kerry, and Laura Bush spoke at a symposium at Georgetown University called “Advancing Afghan Women: Promoting Peace and Progress in Afghanistan.” Clinton said, “We are well aware this is a serious turning point for all the people of Afghanistan . . . in particular for the hard-fought gains that women and girls have been able to enjoy.” When I arrived in Kabul a month later, a lot of women were running away from home, in this new state that was supposedly free from the Taliban. Runaways were getting burned, beaten, shot, or hanged. Farar — home escape — is a moral crime in Afghanistan. A 2012 Human Rights Watch report said that as many as 70 percent of the approximately 700 female prisoners in Afghanistan have been imprisoned for running away from home. They were running from domestic violence, rape, unhappy marriages, forced prostitution, and other kinds of abuse. They ran because they had access to television and cell phones, by means of which they were seeing and hearing about lives better than their own. They learned about foreign-funded shelters, the Human Rights Commission, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs. Since about 80 percent of marriages in Afghanistan are arranged, women often commit farar because they’ve fallen in love with another man. In December 2013, in Baghlan province, I drove through a village where the police were hunting down a man from another village who had fallen in love — without permission — with one of their women. Not long before my arrival, the beheaded bodies of two lovers had washed up in a graveyard near Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand province. Once the women ran, families generally didn’t let them return. Earlier in the year, a girl from Baghlan was returning to her home after running off to a shelter. Her family had accepted her back, but a gang from the village did not. They killed her.

Three systems of law operate in Afghanistan: the penal code imposed by Western governments in the 2001 Bonn Agreement, sharia law, and tribal or customary codes. Virginity exams, for example, are not mentioned in the penal code; they’re a customary practice. But women caught walking unaccompanied by a male are sometimes arrested by the Afghan National Police and subjected to an exam. Because the customary codes are defined variously among regions, tribes, and ethnicities, perpetrators might experience different legal outcomes for the same crimes.

In 2009, President Hamid Karzai signed the Elimination of Violence Against Women Act. The law listed twenty-two acts of violence against women and prescribed punishments for them. It made rape illegal for the first time in Afghanistan. In 2013, the United Nations found that the number of women reporting violent incidents rose by 28 percent. Yet the number of prosecutions under the EVAW law rose by only two. That year, religious authorities accused the law of being “un-Islamic.”

Sayeda Mostafavi is the policy deputy at the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and a lecturer in journalism at Kabul University. Women who run away from home to live in shelters talk to Mostafavi. She sees at least one case a day, and about 6,000 cases a year. “In 2013,” she said, “the number jumped to fifty thousand. It’s up and down. I don’t know why. I don’t know if it’s increasing, but the nature of the violence is more horrific. We’ve never had cases of men cutting off the nose and the mouth. These people have mental problems. You cannot just cut off the nose of a lady.” Mostafavi mentioned the long war. “We also need time to mentally treat everyone in this country.”

In 2012, I read about Malika, a teenage girl in Helmand who ate rat poison after her brothers beat her and openly planned her murder. But the poison didn’t work, so she ran away to the Americans at a nearby forward operating base. The Americans shipped her to a domestic-violence shelter in Kabul. Here, the narrative went blank. Later I read that she’d had children and that her story was “a rare happy ending.”

No Afghan girl had ever run to the Americans before. Malika grew up in the village of Kakaran, near an agricultural district named Marjah. She was a cross-eyed Pashtun girl, and bad luck found her early. When she was three, her father was hanged for theft and her mother was forced to marry another man. Malika was raised by her older brothers, Ismail and Ibrahim. She hated them. They were bad citizens, drug dealers who knew the Taliban. But they all lived together, along with the brothers’ wives and children. All day Malika mended the small mud-brick home, cared for the children, swept, washed clothes, cooked dinner. Her brothers came home in the evenings with their fingers wet from their work with poppies.

Malika was a teenager when she fell in love with Sarwar, a village boy who fixed motorcycles. They had known each other since childhood. But her brothers wanted her to marry an old farmer. Ismail hoped to trade Malika for the farmer’s daughter, whom he wanted to take as a third wife. Sarwar’s mother gave Malika a cell phone so the young lovers could talk in secret. She wanted the two of them together. Malika knew that the last girl in the village to carry a cell phone had been shot for it, but she loved Sarwar and took the phone anyway. Sarwar often called to ask her to run away with him.

One day, a policeman saw Malika with the phone and told some kids to go chase her. The kids asked Malika for her number, but she said she didn’t know it. The policeman showed up at her house and told Ismail about the cell phone. Ismail found a stick and beat Malika from noon to five. She was covered in blood and bruises. Chunks of her hair were on the floor. When Ibrahim came home from the poppy fields and heard what she had done, he said beating her wasn’t worth the time — he wanted to hang her. The brothers invited Malika to eat dinner with them before her execution. She said she wasn’t hungry. They left her on the floor and went to eat.

Malika didn’t want to let them have the pleasure of killing her, so she thought of ways to do it herself. She decided on rat poison. She scooped it into her mouth and waited. She tried to eat more, but it burned and she couldn’t bear the pain. Instead she dragged herself to a prayer rug and prayed. While she was praying something fell from the sky and onto the floor. It was a man, white as a pearl, with a long beard. That’s what she remembered. She guessed it was something from paradise. The bearded man commanded her to run, and so she ran. She grabbed a blanket, threw it over her head, and ran for twenty minutes, up the road and past the cow the Taliban had blown up and the Americans had fixed, until she reached the base. In February 2010, 6,000 Marines had arrived in Marjah to fight the Taliban. Malika always knew where they were. She saw them wandering her fields, standing dark and tall as trees. The Marines plowed the poppy fields. They angered her brothers, and so she liked them.

At the base, the Marines pointed guns at her from the guard towers and yelled in English through loudspeakers. She fake-stabbed her heart to tell her story. Sign language, she said, for “people want to kill me.”

A male interpreter met Malika outside. After hearing her story, the Marines brought her in and tended her wounds. Female doctors hung curtains, closed windows, and removed her clothes. They poured light on Malika’s face and checked for wounds. She had little bruises on the knobs of her spine. They spoke to her in low voices and cooled the pain with sterile rags. When her brothers came looking for her, the Marines called Lt. General Richard P. Mills, commander of the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force/Regional Command Southwest, and asked what they should do. General Mills was the head of all marine combat units in the region, including 20,000 U.S. Marines. The Marines were part of Operation Moshtarak, the largest counterinsurgency offensive in Afghanistan, which involved 10,000 American, Afghan, and allied units. An important goal of counterinsurgency is to win the trust of the local population, and Mills sometimes sent the American soldiers around to local villages to knock on doors, shake hands, and gather intelligence. Afghan men hid their women when the soldiers came. The Americans needed the trust of Afghan women, so they sent female Marines to Marjah, wearing camo and bearing tampons, crank radios, teddy bears, and pamphlets on yeast infections. They called themselves Female Engagement Teams, and they traveled alongside male Marines, bearing M-4s and sixty-pound packs, letting their ponytails hang below their helmets.

The Americans of Operation Moshtarak had dropped into the footprint of old U.S. agricultural projects, into a region once known as Little America. In the late Forties and Fifties, Americans had built dams on the Helmand River and dug canals that carried its water for 300 miles, into the desert. At the same time, Swiss experts arrived to teach the Pashtuns how to use scythes to cut grass for their sheep, defying a 3,000-year-old nomadic tradition. When the British historian Arnold Toynbee visited Helmand to assess the project, in 1960, he argued that this was not a new civilization but “a piece of America inserted into the Afghan landscape.” The project failed: the canal water leached salt from the ground, and wheat yields were among the lowest in the world. In 2007, British troops found themselves dying in the ruins of the old American dam projects. A year later, the British carried a new turbine to the dam — a development project to help Afghanistan finally enter the modern age. The turbine was never installed and has since been abandoned there.

Mills ordered that Malika be transferred by helicopter to nearby Camp Leatherneck. The Marines there had cleared a tent of wounded men and redesignated it for women. They let Malika sleep alongside female Marines and translators. Mills asked a major named Jennifer Larsen to take care of Malika. Major Larsen was a liaison officer between the U.S. State Department and the U.S. Marine Corps. She had flown a CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter during the free elections in Iraq. She asked Malika what had happened to her eye. Malika said she didn’t know but thought maybe she got hit when she was a kid. Larsen asked about Malika’s shoes. They looked expensive. Malika said she had sold her brothers’ heroin to buy them.

The translators taught Malika Dari, one of Afghanistan’s official languages, and a few words in English. Larsen brought her food from the chow hall, and they ate together on a couch in front of a TV. Larsen stayed in the tent with Malika half the day, every day, for three weeks, and tried to learn about her life in Helmand. The women grew fond of each other. Malika called Larsen her khor, the Pashto word for “sister.” (Larsen thought it sounded like “whore,” and soon the female Marines started calling one another whores.) Malika said that she used to listen to music when she cleaned, so Larsen gave her an emergency radio, which Malika listened to while dancing around the tent. Malika ate ice cream and Doritos and watched romantic comedies. She loved The Mask of Zorro. Her first word in English was “kiss.” She learned it watching Antonio Banderas.

The village elders in Helmand were not happy. They sent a man who called himself Haji Karim to serve as Malika’s male escort. Mostly she ignored him. Karim ate in the chow hall with the men and told everybody how much he loved America. He got ice cream and sat at the head table, where the general sat, to feel important. When he complained of a toothache, a Navy dentist offered to fix it. Every day Karim asked Malika to return home. When Malika told him that she would rather live with foreigners, he walked off and never came back.

In Marjah, the Taliban told everybody that Malika was in America getting raped. “This is the true cost of the American occupation,” they said. “They steal and rape our women.”

The Americans wanted to make sure that the Afghans knew their intentions were good, so Larsen and Malika flew to Lashkar Gah for a jirga, a meeting among a council of elders. At the jirga, the tribal leaders would negotiate with the Americans about Malika. Human rights advocates would be there, as would legal teams, members of the provincial leadership, and members of the national government.

Larsen handed Malika over to the Afghans for two nights. They kept her in a juvenile prison and subjected her to a gynecological exam. Larsen worried that the Afghans would blame the Marines if the exam suggested she were not a virgin. Malika had told Larsen about an uncle who abused her, but it wasn’t clear whether that meant rape. In the end, Malika passed the test.

Ismail and Ibrahim showed up unannounced in the morning to attend the jirga. They brought Karim, who cursed America. Larsen, who had no idea they were coming, tried to shield Malika with her North Face jacket, in case they planned to throw acid. But Malika walked out and sat in the grass with her back to them, a sign of disrespect. One of Ismail’s wives flipped her burka, showed her face, got down on her knees, and begged Malika to come home. We promise we won’t kill you, she said. Malika told her, You’re just as bad as the men.

When it was over, the Afghans agreed to send Malika to Kabul as long as the Marines agreed never to contact her again. The next morning, Malika and Larsen flew together in a cargo plane to Kabul International Airport, where Larsen handed Malika off.

The parliamentary representative of Helmand province told me that she didn’t believe Malika’s story. “No woman would ever run off with foreigners,” she said. The Ministry of Women’s Affairs office in Helmand hadn’t heard about the case. A Helmand-based journalist who was later murdered told me that he didn’t know about Malika, either. He called a tribal leader named Mazam to ask about Malika, and Mazam said that he had never heard of her. Finally, a member of the provincial consulate in Helmand said that she’d heard the story about “the girl from Marjah whose brothers wanted to kill her.” The woman had helped move Malika to a shelter called Humanitarian Assistance for the Women and Children of Afghanistan. She told me to contact Shafiqa Noori, HAWCA’s defense lawyer. “She’s not here,” Noori said the first time I called. “We don’t know. And don’t talk to people about Malika.” She said later she’d been worried that I wanted to hurt Malika.

On a Saturday, I drove to HAWCA’s headquarters, along with Ahmer, my interpreter. The graffiti across the street from the office said yankee go home.

A bedroom at a WAW shelter in Kabul. The shelter has fifty beds, which are often not enough for the women who seek help

Noori welcomed us inside. We sat around a conference table in a dark room, eating lemon cake served on pink Kleenex. She asked questions: Why did I want to meet the girl? Where was I coming from? “The shelter receives a lot of death threats,” she said. “Relatives come to my house and say ‘I will kill you’ to my face.”

After admitting that she knew Malika, she disappeared into a back room and returned with a copy of a wedding certificate. On July 31, 2011, Malika had married a policeman named Aziz Agha. “But I have no idea how to reach them.”

I asked her about Malika’s time at the shelter.

“She was nervous,” Noori said. “Lost. Making noise about that boy she loved in Helmand. She cried all day. Over and over again Malika said she wanted to marry him. I called the head of Women’s Affairs in Helmand for help.” Noori found Sarwar’s phone number and told him that Malika wanted to see him, as they were now free to wed. Sarwar said it was too late — he had married another woman. Noori yelled at him: Malika left home for your sake. Why did you do this?

Sarwar apologized. He said her brothers would have killed him.

“I told Malika to forget about that boy. But her heart broke.” Her psychological state deteriorated. They gave her mental-health exams. Malika said that without Sarwar she wanted either to die or leave the country. Call the coalition forces! Malika said. She believed they were going to help her get to America. And so Noori called the coalition forces. “But the coalition forces were not picking up the phone. I told her I was sorry, but Women’s Affairs won’t let foreigners take women out of Afghanistan.”

Noori agreed to let me visit the shelter, but she insisted that I be picked up by HAWCA’s hired driver from a location of their choosing. I was to arrive alone, without Ahmer.

The next morning, I waited for the car next to some goats near the passport office. My driver, Habib, offered to follow me in case of kidnapping. A friend had introduced me to Habib when I arrived in Kabul. He was a short, round man with thick graying hair and immense, ruddy cheekbones. He did not speak English. His eyelashes curved like the necks of swans.

An armored vehicle pulled up. Noori was smiling in the back seat when I stepped inside. Habib followed, but eventually he disappeared into the dust, traffic, and livestock.

We drove for about twenty minutes and stopped outside an unmarked security gate. Kabul is a city of walls; another gate, another door patched on a blast wall. Everything is covered in anonymizing dust. The gate groaned, and we parked inside a dimly lit garage crowded with guards. “The neighbors don’t even know it’s a shelter,” Noori said. “They think it’s a hospital for mentally ill women.” A Batman sheet hung from the pink wall. We walked to a courtyard where a woman collected leaves beneath a tree that was tangled with laundry lines and women’s clothes. “That’s the insane lady,” Noori said. The woman walked up to me. “What’s she saying?” I asked. “She wants to tell you that she has a sore throat,” Noori said.

HAWCA is staffed with nurses, doctors, vocational trainers, cooks, guards, and attorneys. The shelter can hold fifty women; there were twenty-seven, along with nine children, when I arrived. Most were downstairs, huddled in a large room overlooking the courtyard. A few napped in the sun, barely opening their eyes to look at me before stretching and curling back up. On average, domestic-violence victims spent one to three months there, but many stayed more than a year. “We never kick them out,” Noori said.

The women slept in bunk beds. They passed their days in the sewing room, the classroom for English lessons, and the nurse’s room, which was decorated with half-finished embroideries and had a poster on the wall that showed a human body with the stomach removed. Each organ was labeled with a letter — a, b, c, d — and connected to images of disease-ravaged cases. Another poster showed a burned baby with the warning burn prevention is prevention of disability and death. “It’s for the women who believe death by burning is instant,” Noori said.

Mara, twenty-eight, had a wide face and pale eyes. She’d been here the longest, two years and two months. She had married a heroin addict who later threatened to kill their children. Every day, he injected himself, beat Mara, injected himself, beat Mara. She wanted a divorce. He sold the children. Later, the police found them with another family.

“Why didn’t you bring the children here?” I asked.

“It would have been better if God didn’t give me children,” she said.

“In Afghanistan, men won’t accept the children of new wives,” Noori said. “So she had to leave them. Otherwise she would never get out of the shelter. Even now, no one wants her. Maybe if we find a man with three wives? Maybe he would take her?” Marriage was one of the only ways women could leave the shelter. Afghanistan is no place for a single woman. “Maybe one day,” she said, “it will be acceptable for a group of widows to live together.”

We drove back to HAWCA’s headquarters. Inside, Noori said, “Do you want to see the secret room of women?” We walked through two heavy bolted doors and down a dark stairway. About twenty women huddled around bread and tea. There were small windows way up high where the earth began. Sunlight spilled into the room. “These are just the ones who arrived today,” Noori said. All these lives, trapped in sudden, brief intimacy. In the corner, a mother sang quietly to the baby of her rapist.

At a shelter run by Women for Afghan Women, a defense lawyer named Benafsha Efaf Amiri introduced me to Gulchira, a fifteen-year-old from Ghazni province. Around nine o’clock one night, five Taliban commanders entered her bedroom and dragged her out of the house, she told me. They transported her to Pakistan and imprisoned her there.

“They raped you?” I said.

“The famous commander raped me,” she said. “He wanted to marry me, but because I was so small, my father rejected the proposal. About sixteen months I was in Pakistan. A place like a prison.” She chewed on the end of her sweater. “I know the names of all of them. I know their faces.”

One day, one of the commanders drove Gulchira back to Kabul. He dropped her at the Human Rights Commission. It was not kindness that made him do it. He’d been in a fight with the famous commander and wanted revenge.

A twenty-three-year-old woman whose stepmother poured acid on her nose at a young age to keep her from competing with her stepsisters for a good husband. The woman escaped to a WAW shelter in Kabul after her father tried to marry her off to a seventy-year-old man for money

Gulchira was crying now. I told her she didn’t have to talk about the commander anymore.

“That’s not why she’s crying,” Amiri said. “She’s crying because her father is in prison. Her father killed the commander. That’s why. He’s a killer.”

Bibi Mariam was twenty-eight. She had black stains around her eyes. “I have had it worse than anyone in the shelter,” she said. Bibi had believed that there was a man in Australia who loved her. Her story was full of trickery by the man’s mother, who had found Bibi at a family wedding and persuaded her that her son actually wanted to marry a poor peasant girl in Afghanistan whom he’d never met. Bibi agreed to marry the woman’s son, but he didn’t show on their wedding day. The woman held up a photograph of him, and the wedding went on as planned. When Bibi showed up in Australia, her new husband and his family started beating her. When she got pregnant, she expected some relief, but the beatings didn’t stop. It was Hajar they were hitting, the child who was now sitting on Bibi’s lap. Bibi showed me Hajar’s skin, which was black and sunken like rot on fruit. “Australia was full of different kinds of violence that even in Afghanistan no one is used to,” she said.

After Hajar was born, Bibi threatened to turn herself in to the police. The mother dragged her back to Kabul. After a few days, the mother told Bibi she was going shopping. She’d be back in an hour. Five days later Bibi called her husband. “Your mother is missing,” she said. He told her that his mother was already back in Australia. “Have a good life,” he said. “Goodbye.”

A shelter worker looked over at me. She had a plain face, which shone brightly, like the moon. “My mental state is not good,” she said. “I’m always very busy thinking about these stories. It hurts my husband, and I cannot manage my personal life. The nightmares are in my home now. My mental state is not okay.” She kept repeating her sentences. “How is your mental state after coming to Afghanistan?” she asked.

On November 19, 2001, barely a month after the war began, the United States Institute of Peace held a forum called “Rebuilding Afghanistan: Establishing Security and the Rule of Law.” Participants included experts on Afghan law and legal traditions, and specialists on the prosecution of terrorists, civilian policing, and the role of peacekeeping forces. In the pursuant report, USIP wrote that qadi courts — mostly run by the Taliban — were respected by the rural communities, and that, “as a consequence, no attempt should be made to impose any other legal system or structure on the rural areas of the country. It is not evident that it is needed, and it would not work.”

This foresight seems at odds with the $904 million investment the United States made in “rule of law” funding between 2002 and 2010. Ben Tramposh, a former rule-of-law field-support officer for NATO, explained it to me this way: “The initial push was really to develop Kabul. The predominant thought among policy makers was: As goes Kabul, there goes the rest of Afghanistan. But there was a shift in that thinking around 2009. A recognition that the cog wasn’t effectively turning the wheel.” Tramposh now works as an adviser for a legal-education development program, which, he believes, has been much more effective than direct foreign involvement in legal reform. “I don’t think it’s a revelation to anyone that you can’t just cut and paste a justice system. Nonetheless, somewhere along the line we seemed to believe that if we put together the best and brightest from the international community with key officials from the Afghan government, we might be able to invent something which combined Western notions of due process and fair trials with Afghan culture and tradition. It’s been an expensive endeavor, and the legitimacy and effectiveness of the so-called formal justice system is still seriously in question. No matter how impressive our credentials, those of us working here will always be outsiders to some extent. We need to accept our role as ambassadors rather than saviors.”

A twenty-year-old woman severely disfigured by acid, which was poured on her as she slept by a man whose marriage proposal she had rejected

Another expert on Afghanistan told me that much of the money invested in the Afghan legal system was spent on foreign experts. “Basically nothing worked,” he said. I asked whether counterinsurgency policy was used more as a propaganda tool than as an effective means of fighting the insurgency. “The surge,” he said, “was totally bullshit from the beginning. The Taliban are coming back very quickly. The CIA is leaving and don’t care much about the people they’re leaving behind. We just don’t have enough money to continue financing these wars.” For much of the country, he explained, the Taliban’s sharia system would function as the normal judicial system. “There will be a new parliament next year and you will see a lot of fundamentalist people. The foreigners will not have the power to stop them. We don’t have leverage in Afghanistan anymore.”

He has little hope that judicial reform will take place in the new government. “To win a case at the Supreme Court, you have to give five thousand to one million dollars. Everyone in Kabul knows it. In rural areas the Taliban are killing off our judges. They have killed a hundred to a hundred fifty judges in the last few years. They call the judges and say, ‘We don’t want you to go to this place, and we’ll kill you if you do.’ The judges are the Taliban’s new priority. They kidnap them or kill them. Killing is the last step of a complex system of keeping judges outside the cities. Basically, everything is going in the wrong direction. I have nothing positive to say.”

After a year at the shelter, Malika was sent to the office of Mohammad Latif Rasikh, a HAWCA legal adviser, at the Ministry of Women’s Affairs. Rasikh already knew Malika’s story. He was one of the Afghans who had taken her from Larsen at the Kabul airport. “Sir, I’m really bored,” Malika told him. “I keep waiting and waiting.”

“Well, what do you want?” Rasikh said.

Malika gave him her requirements: “A loving and respectful husband with no other wives.” Rasikh said that might be difficult. But since more and more women had been running away from home, he had started keeping a list of eligible men in his office. The unofficial work of the ministry, he called it. He passed Malika’s request on to his most trusted source of single men, Lieutenant Colonel Gul Mohammad Pechwal. Pechwal commanded a brigade in the Afghan National Police in Kabul, and he kept his own list of single men among his soldiers.

Rasikh told Pechwal, “A Pashtun woman from Helmand is looking for a good man to marry. Do you have anybody?”

Pechwal called one of his soldiers, a bearlike sergeant named Aziz, who had served as the colonel’s bodyguard. “Would you like to marry?” Pechwal asked. “I have a girl. If you don’t like her, then I can find you another.” Pechwal and Rasikh arranged for Malika to meet Aziz on a blind date of sorts, at the ministry.

Malika asked Aziz questions based on the stories she had heard at the shelter: Do you shoot heroin? Do you already have a wife? A week later they met again, this time at a court to be married.

When I arrived at the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the electricity was out. I found a few women passed out in chairs. Another was asleep at her desk. Many confessed they were working because they didn’t want to be at home, where their husbands beat them.

A media officer at the ministry had bruises all over her arms. Her husband beat her. The Taliban left notes on her door. Her husband begged her to quit. She said she would quit if he got a job. They had two children. Her husband’s family, she believed, wanted her dead. Her mother-in-law tried to blow her up by putting gasoline in her bedroom lamp.

Rasikh told me that the ministry has had difficulties in the past finding candidates for women who want husbands. “We always try to find a proper candidate. Men who are worthy of being husbands. We are short on husbands, actually. If you know any, send them our way.” He wanted to start a new ministry in Kabul devoted entirely to matchmaking. He would call it the Ministry of Marriage and Divorce. “For those men who really deserve wives!”

I asked whether this was a common practice among lawyers at the ministry. “Others have their own lists and contacts,” he said.

“My brother needs a wife,” Ahmer said. “Maybe you know someone?”

Rasikh pulled a few passport-size photos from his pocket. “I have just the thing.” He knew a forty-year-old woman. Ahmer said that forty would be very old for his brother. Rasikh said he would keep looking.

Then he asked me whether Malika’s story had changed at all. “You never get the truth from the first inception of the girl’s story,” he said. “They only give you enough to know they’re desperate but rarely enough to shame themselves. If it involves housework or torture, well, then there are not a lot of lies. But the police collect a lot of women from whorehouses, and when the government brings the prostitutes to me, they tell lots of lies.” He mentioned a father who came to the ministry looking for his daughter. She was a runaway whose lover had left her at a whorehouse for some cash. When the girl showed up at the ministry, she said she had no father. But her father had been in the back room the whole time — he had slept there for thirty-nine nights, waiting for his daughter.

Lt. Colonel Pechwal, the 1st Battalion commander for supplies and logistics in the Afghan National Police, leader of 250 men, lived near the graveyard in the neighborhood of Sar-e Kotal, on a road lined with the rubble of Soviet tanks. Goats foraged among the rusting frames. It was nearing noon when Ahmer and I hiked the steep road to the gated entrance of the commander’s home. A guard let us in and led us up two flights of stairs, to a wide carpeted room. The windows blistered with cold sunlight. Pechwal was on the floor, leaning against the wall with his legs spread. His eyes were closed, and he appeared to be savoring the warmth of a gas heater. He wore oversize ANP pants and a stiff camouflage jacket that hung over his shoulders like a cape. He had a thick horseshoe mustache.

“My house has six rooms, three bathrooms, and two wives,” he said. “To keep the balance, I sleep with one wife to my left, and one to my right.”

Malika and her husband, Aziz, stepped into the room and sat down next to Pechwal. She had two children. The younger was a baby girl, who was wearing a pink outfit, the older a boy, in a checkered sweater.

Malika lifted her shirt and prepared her child for breast-feeding. The baby’s lips folded back like petals. Malika sweat through her dress. She squeezed the baby’s toes. Right then, the commander’s phone rang. Its tone was Vivaldi.

I told Malika that I had spoken with Major Larsen before I arrived. Larsen felt guilty about abandoning Malika in Kabul and wanted me to ask her whether she hated the Americans. Malika felt appreciative but disappointed. She’d thought the Marines were going to take her to America.

Aziz and Malika had moved to Parwan province, just north of Kabul. Aziz was often gone for months at a time, training with the ANP in places she’d never been — Wardak, Logar, Kunar. The men weren’t allowed cell phones. Malika sometimes called the commander and pretended to be sick so her husband would come home. When Aziz showed up, Malika would say, “I’m fine. I just don’t want to be alone.” But after their first child was born, Malika stopped calling.

The commander said he received a lot of calls from Rasikh and the shelters. After Aziz met Malika, Pechwal even called Aziz’s father and mother to make sure they would approve. He said, “Listen, your son likes this girl, so, please, don’t say they can’t marry because it’s some Pashtun thing.”

According to Pechwal, the ANP and the shelters worked closely together. He found his second wife in a shelter in Kabul. She was hiding from her mentally ill husband. The shelter, he said, gave her an album full of single men. Pechwal had put himself on the list of eligible men. “I like this one,” she said, and pointed to the thick-lashed commander. He drove to the shelter that day and brought her home.

“I’ll leave you in the room with my wives,” he said to me.

“Why would you do that?” I said.

“To look at their faces,” he said. “Just look. You have put these women in danger by putting them in shelters, and now you’re leaving. We are isolated. Who is going to be responsible when the Taliban come back?”

For lunch we ate dried goat meat. Malika left and returned in a new outfit — a hot-pink abaya. She had plucked eyebrows and painted nails. “Thank God I didn’t marry that boy in Helmand,” she said.

“She’s acting this way because the King is here,” Ahmer said in English, referring to Pechwal.

“Can the King leave?” I said.

Aziz and Pechwal agreed to step out so that we could speak with Malika alone. “But these rooms are cold like hell,” Aziz said. He slammed the door.

Malika leaned forward and whispered, “My brothers came to Kabul looking for me. They came three times. My husband only knows about one time. What can you do for me?”

Before she finished, her phone rang. It was Aziz. He kept Malika on the phone, taking all our time. After the men returned, I offered to visit Malika in Parwan while Aziz was at work. Pechwal rolled his head at me. “Gang groups in the area. I wouldn’t recommend it.”

I asked Malika a few more questions before Aziz interrupted. He decided to narrate the geography of the scars on his leg. Pechwal sat loose-limbed in the corner, looking at the ceiling, feeling the air with his fingers. “I saw an Afghan military expert talking on TV in London,” he said. “What does he know? I’m a military officer for thirty-five years, and I know about each issue in the country because I’m here, so please don’t talk about my country from thousands of miles away. Now we have thirty-eight foreign countries here but we cannot defeat a small number of Taliban? Afghanistan has thirty-four provinces. That’s four countries extra. So what is the reason they cannot establish security?” After a moment’s thought, he brightened. “The war is not a war,” he said, “it is something else.”

Dial 6464 from anywhere in Afghanistan, and you’ll be directed to a female operator in Kabul. The Family Support Hotline takes more than 180 calls every day. In 2013 they received more than 16,000 calls, from thirty different provinces. Wahid Bik, a well-dressed British Afghan with a degree from Coventry University, started the call center in 2012 with funds from the Canadian government.

The call room is a sterile office full of women with headsets clamped over their hijabs. All eleven female operators are trained lawyers, and they work in consultation with a male religious scholar. Just across the hall is another room for the operators. “A meditation room,” Bik said. “For the dizzying or traumatic calls.”

The calls vary in nature: “Why can’t we have children?” “What does Islam say about four wives?” “Can I have another wife?” “Why can’t I get an erection?” “We are married, but why doesn’t she want me? She used to want me.” “How do I become intimate with my wife?” “I lost my husband, and they’re forcing me to marry my brother-in-law.” “What is the law about beating?” “I married a man and then I found out he was insane.”

Three quarters of the callers are men. “Men call and ask whether they have the right to beat women,” Bik said. “Women call and don’t know they have the right not to be beaten.” Men want to know how their actions fit legally with Islam, and about their sex lives. “It’s anonymous,” he said. “Very secretive. In Afghanistan, it’s extremely rare for men to talk about their sexual issues. It’s shocking.”

I met Fawzia Koofi, a member of Afghanistan’s parliament, on Christmas Eve, at a café at the Serena Hotel in Kabul. “Violence against women is now a matter of revenge against the foreigners,” she told me, “because women’s rights are one of the achievements of the international community. It’s a structured violence against women.”

Koofi showed me an iPhone photo of a girl with no lips. The woman’s husband had chopped off her nose and lips because she wouldn’t give him her jewelry. He needed money for heroin. “We have raised the awareness that women are human beings, but we have not built the capacity of the man to tolerate such a woman.” Koofi had posted the photo on Facebook. “Get your nose chopped off in Afghanistan, and you become an icon for women’s rights in the West,” she told me.

“What do you guys do for fun?” I asked the fifteen-year-olds at Bagh-i-Shahr Ara, the Women’s Garden, an eight-acre enclosure in the Shahrara neighborhood of Kabul.

“House chores,” one said.

“I watch Bollywood,” said another. “I Hate Luv Storys. It’s an Indian movie, and the woman loves Bollywood so much her life comes to resemble it.”

“We don’t hang out at night. Only during the day.”

“What do you think of the boys in Kabul?”

“I don’t like the boys. Good boys, maybe. But not bad boys.”

One of the girls was older. Her name was Mina, and she was wearing a silver headband. She’d just graduated from Kabul University and wanted to study pharmacology. “I don’t date. I give all my decisions to my family. It’s just too hard to trust boys.”

“Yeah. If we run away, then our family will hate us. They will beat us. Whatever they chose for us to do, we have to accept it. But they let us choose the boys. They won’t make us.”

“Also, our mothers didn’t even tell us about our periods. I was very afraid. I told my sister, and she gave me a diaper to use. We were outside Kabul, in a remote area.”

They loved Titanic — a movie about doomed love. Titanic pens. Titanic shampoo. The Taliban had outlawed the Leonardo DiCaprio haircut.

At the garden’s dress shop, an older woman curled over a heater. She told me women sometimes fled honor killings and came to Bagh-i-Shahr Ara. Workers find the girls and take them to shelters. This woman imported fabrics and handmade items from Tajikistan and India to sell in her store. “Even if they have no money for food,” she said, laying out a fabric, “Afghan women will find a way to be stylish.” The Women’s Garden is also where girls come to talk to boys on their cell phones.

The woman told me a story about the day, decades earlier, that her teacher brought her and her classmates on a field trip to see a poor boy. The poor boy lived with a poor girl. The two had fallen in love, and the girl had quit school to run away with him. “Never end up like the poor girl,” the teacher had said.

After our meeting at Pechwal’s house, the colonel called and said he’d changed his mind about our visit to Parwan province. It would be fine to visit. He said he’d arrange an escort. But then he called again, having changed his mind a second time. He continued to vacillate until I decided that it wasn’t worth going. Then, on a Friday, Ahmer and I were talking to street kids outside Sar-e Chowk, and Malika called. I said I’d call her back. Habib drove us to a quiet street. Malika was crying when she answered the phone. A truck with a mounted machine gun had ambushed her husband. Armed men had beat Aziz and left him on the side of the road. He was being brought back from Wardak as we spoke.

Malika said that she didn’t know the names of the attackers, but that men had been calling, including her brothers. They were always changing their numbers. She was always changing hers. She didn’t know what to do, so she answered the phone.

“I don’t really understand,” she said. “They fled, but I don’t know where. My life is in danger. God forbid if something happened to my husband. What am I going to do? Go back to the shelter? ‘We swear to God we will not leave you alive. If we find you, we will kill you and your children, don’t worry.’ That’s what they said to my husband.”

My phone ran out of money and the call died. Habib grumbled. “The husband is just using her,” he said. “The husband doesn’t give a shit about her.” Habib also said that he’d overheard Aziz talking to Malika on the phone when we’d visited Pechwal’s house.

“The husband said, ‘I will have you eat dirt.’ He said, ‘You daughter of a donkey. You have eaten donkey’s milk.’ He said, ‘You stupid bitch. Do you understand what I’m saying? Tell them to take us to America. America.’ ” The car shook with Habib’s voice. “He said, ‘How long am I going to work as a soldier in this fucking country?”

Habib paused. “Oh,” he said. “He also told her: ‘I will have God destroy them.’ ”

We called her again. “What can I say?” Malika said. “You didn’t come to Parwan. They will kill my husband and my children.” She could hardly speak. “I’m being hunted.”

Pashtunwali is the customary code of the Pashtuns. It holds that women are inferior to men, though men are supposed to protect women. Pashtunwali traces its origins back a millennium but is consistently conflated with Islamic law, which dates to the seventh century. Even Afghanistan’s religious scholars are unclear where the dividing lines run between custom and religious law. On March 2, 2012, the Ulema Council — the appointed religious authority of Afghanistan — declared, “Men are fundamental and women are secondary.”

Hamid Khan, a senior program officer at the Rule of Law Center at USIP, is working to clarify the fault lines between sharia and the customary codes. “While the Koran states that men and women are equal,” he told me, “religious equality is not the same as equality of social roles.”

In Afghanistan, Islamic law has long been considered the transcendent source of legal authority. But most informal dispute-settlement bodies — jirgas, for instance — invoke a blend of customary and tribal norms as well as local interpretations of Islamic law.

When I asked Khan about the current status of women in Afghanistan, he said America’s failure had to do less with policy efforts than with questions of competing authorities. “During the Bonn Agreement,” he said, “different countries were put in charge of different areas.” The Italians were in charge of criminal law, the Germans in charge of the police. It wasn’t well coordinated. It was meant to be temporary. “We said, ‘Here, these are your rights from the 2004 constitution.’ This is all well and good, but many don’t regard the elected government as legitimate, because it’s an extension of the United States. The same is true of women’s shelters and NGOs. We need to widen the discourse beyond the current constitution. Even if women are gaining rights, the gains remain illegitimate because they originated from a Western source.”

Pashtuns are the ethnic majority in Afghanistan. Malika is Pashtun, and so are the Taliban. The Pashtun nation sweeps in a crescent-moon shape from southern Afghanistan to northern Pakistan. In 1893, the British drew a line through the Pashtun nation and called it the Durand Line. This now marks the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ghani Khan, a celebrated modern Pashtun poet, observed that Pashtuns would rather burn their own home than see their brother rule in it.

The Pashtun concept of badal (revenge) is often harsher than the Islamic concept of quisas (blood for blood). Infidelity by a woman requires the blood of her and her lover.

Davoud, aged twenty-eight, told me how he offered rides to beautiful women on the streets of Kabul and ignored everyone else. He liked to look at them in the rearview mirror and say, “You know, you are a very beautiful girl.” One girl out of a hundred (he’d counted) had slept with him. Davoud looked like an Afghan John Cusack. He owned a white tracksuit and knew the geography of available women in Kabul — where to find them, how to win them. For years he slipped into homes at night, made love to daughters, and left soundlessly through windows. A few times he encountered fathers in the dark, but he always escaped. Once, he leapt naked from a high window.

Davoud gathered a square of lamb into a fold of naan. We were at his second-favorite restaurant in Kabul; his favorite is AFC — Afghan Fried Chicken. Davoud ordered two of everything. He is famous among his friends for his appetite.

One time Davoud and a rich friend picked up a couple of seventeen-year-olds in burkas outside the mall for $200 each. He knew they were prostitutes because of the way they flapped their empty plastic bags like prayer flags in the wind. Davoud’s rich friend owned a house with plenty of rooms. Rooms were important, he told me, because finding a place to have sex with a girl in Kabul isn’t easy. “ ‘Let’s go to your house?’ ‘No, my husband will kill you.’ ‘Let’s go to your father’s house?’ ‘No, my father will behead you.’ ‘My friend has an empty house, let’s sleep together there?’ ‘Sure!’ ”

At Finest, Kabul’s Western-style grocery store, girls and boys dropped folded bits of paper with phone numbers near the overpriced Frosted Flakes and the cooler of imported cheese.

“But the best places to bring women are the gardens,” he said. “The gardens of Kabul are the most beautiful. You can bring a girl there. There is also a desert nearby to make love to the prostitutes.”

I told Davoud that I was disappointed because Badam Bagh, Kabul’s women’s prison, had stopped letting journalists inside. “Don’t worry,” he said. “I know a girl who just got out. You can talk to her.” That girl was Mariam, his seventeen-year-old ex-girlfriend.

Badam Bagh, which means “almond garden” in Dari, is located on the eastern edge of the city and currently holds about 200 inmates. The majority of women at Badam Bagh are in trouble for running away, which is technically not a crime; most are charged with zina, “immorality.” Even if a girl or woman is raped, she can be imprisoned for zina. Inmates also included victims of arranged marriages who had run away from beatings, stabbings, or burnings. Others had fled forced prostitution or even kidnapping.

“They smoke the hash,” Davoud said about the prison. “They have the sex. I didn’t know Mariam was there until I got the phone call. She told me, ‘Hey, I was just having sex with a girl. There is no man to do it with here. I miss you a lot!’ ”

Davoud leaned back in his chair. “I was careful after I found out she was in jail. I stopped taking so many risks with women.” If he were to be caught, he said, the police would send him to Pul-e-Charkhi prison, alongside the insurgents and murderers. “There’s a whole floor for moral criminals.”

Mariam lived in one of the poorest neighborhoods of Kabul. Sewage cleaved the streets. Lost helium balloons hung over the garbage piles. The door to Mariam’s home was a small hole in a mud wall.

She sat cross-legged on a long, flat pillow. She was beautiful, with a famished frame and full lips. It was the same room where the women and children and babies slept.

As soon as we arrived, Davoud started kissing her. She blushed and pushed him away. He kissed her again. She smiled. I asked what happened on the night of her arrest. She sat up on her knees.

“I was at home,” she said. “After everyone was in bed I met my boyfriend in the other room. We took our clothes off, and my father caught us.” She didn’t know why her father woke up. Maybe he heard the noise, or maybe he had to go to the bathroom. But her father called the police, and Mariam and her boyfriend both went to jail.

The police subjected Mariam to a hymen check. I asked her about it. She said she was spread on all fours with her pants off, but with her shirt left on. The results went to the courts, where judges declared her innocent. Months later she was back at home.

“But you aren’t a virgin?” I said.

“Oh, we do it in the backside,” Davoud said. “Is America more of a frontside or a backside country?”

One day, some big girls came into Mariam’s room and looked her over. They told her to get into the bunk bed. The big girls gestured to the bottom bunk, which was curtained by a white sheet tucked into the metal frame. They told her to spread her legs.

Mariam could have fought back. She could have screamed. But the big girls had already thought of this. They threatened to tell the guards about her phone. Cell phones were illegal at the prison.

I asked what happened. It was gentle enough, she said, getting raped by a girl.

Habib said he knew how to find prostitutes. They were waiting by the banana stands in the falling snow. He’d been with many in the past. A lot of runaways ended up on the streets, though no one knew the exact numbers. Sometimes women worked as prostitutes because their husbands forced them into it — it was extra income for the family. I suggested to Habib that I hide in the back of his Corolla, under a blanket, while he pretended to pick up women. He agreed, but in the morning, he changed his mind. “I won’t do it. If the police find an American woman under a blanket in the back of my car, this will be very bad for me.”

I decided to go undercover as a prostitute, which meant only that I needed to put on a burka and sit in the back of the car with Ahmer. We’d leave the front seat empty while Habib looked for women. We hoped they would assume that Ahmer had picked me up and that the car was safe for them to step into. If the police stopped us, we’d say we were interviewing women about the Bilateral Security Agreement. I wore a down coat beneath my burka. I looked huge.

As he drove, Habib talked about all the sex he’d had in the back of the car. “I used to pick up three girls a day,” he said. Customers had tried to have sex in the back seat while Habib was working as a taxi driver. Once he picked up two kids who asked him to dim the lights. Habib watched them. They kept getting closer. Then the boy had the girl’s breast in his mouth. He threw the kids out of the car. “I’m not a pimp,” he said.

Habib said he’d once found a pretty girl in need of a mullah. Habib had a beard at the time, and so he figured he could pass as one. He told the woman that he sat in a pool of water at night and the jinni king gave him words from Allah. The pretty girl believed Habib and confessed her need for prayers. I cannot have children, she said. Mullah Habib responded. First he pretended to receive a word from Allah. You will need to have intercourse with a man who is not your husband and mix your liquid with the sperm of this man, he said. Bring this liquid to Mullah Habib and he will use the liquid to write spiritual words on the walls.

The pretty girl said, “Yes, Mullah Habib, but where do I find a man?” “Don’t worry, my dear, I’m here.” The pretty girl agreed. But there was a problem: Mullah Habib didn’t know any places to have sex in Kabul. “Do you know?” he asked. The pretty girl shook her head. Habib spent the next month trying to find a room. Finally, he put her in the front seat of his taxi and told her to spread her legs.

We drove over a bridge that was famous for opium addicts and past the shop where Karzai had bought $3,000 hats made from the skin of newborn lambs. We reached Dasht-e-Barchi, the neighborhood where, Habib said, the Hazara lived and the prostitutes worked. Habib assured me, “This area is famous for the vagina market.” The fruit vendors sold heaps of pomegranates, oranges, and bananas. Piles of oily nuts, their shells as thick as the carapace of a cockroach.

He added, “If a girl is riding in front then she’s probably there for you to play with the vagina.”

Afghan men had an eye for the subtlety of female movements beneath a veil. Signs and symbols. You knew she was a prostitute if she smacked her gum like a man. Or if she had a bump on the back of her head that made the burka bulbous around the neck. Or if she walked tack tack tack like a horse and wore sexy shiny boots. Or if she was fluent in hand movements flashed at the men like gang signs. Or, of course, if she fluttered empty plastic bags. The signs changed depending who was asked.

“There’s one,” Ahmer said. “Oh wait, she’s stalling. She’s looking in her purse. She’s talking to a soldier in a North Face.” We followed her with our windows down. “Need a taxi?” Habib patted the front seat.

“I’m going to a shop,” she said.

“This is just one of their tricks,” Ahmer whispered.

“What’s the trick? How do you know?”

“The one who actually needs a taxi won’t look hot and sexy. She is hot and sexy.”

Nearby, a blue, a black, and a white burka stood in a circle.

“See that burka with sexy hands,” Ahmer said. “Excuse my language, but that woman is on her way to be fucked.”

Finally, a woman in tiny high heels slipped into the car.

“Where to?” Habib said. She mentioned a building up the road. “Yes, dear,” Habib said.

A truck pulled in front of us. Inside, a man warmed himself around a lantern’s bright flame.

“Sweetheart,” Habib said. “Where you going?”

Again, the woman mentioned the building up ahead.

“Come on,” Habib said. “Come close.”

Habib offered his hand. The woman pressed her body to the door.

“I’ll get off here,” she said.

Habib pulled over. She opened the door, stuck her head back into the car, and screamed, “You bastard pimp!” She left a wad of bills on the dash.

Habib was flustered. He decided to buy oranges. When he returned to the car he ate one. “Why aren’t we driving?” I asked.

“See that car right there?” Ahmer said. “That’s my dad. We have to wait for him to leave.”

The women didn’t seem to like Habib.

“No, Habib is good,” Ahmer said. “Habib looks older. Like an expert. Like he’s fucked a lot.”

“There used to be a lot of girls roadside,” Habib said. “God willing, I’ll find one.”

Habib blamed us for the trouble. We asked a taxi driver, “Where do the girls work?” The driver knew two spots: Silo Road and Airport Road. We followed Habib around for a bit in the taxi, but soon there were no people around at all. The snow was thick, and it was impossible to see anything but the occasional smear. We stopped on the side of the road.

We ate the rest of the oranges and waited for the snow to pass.

“You know,” Habib said. “The best way to make love to a woman in Kabul is easy. You fill your car with warm flatbread, straight from the bakery, until the windows steam. Then you can no longer see outside and no one can see inside.”

Five hundred years ago the Timurids and the Mughals turned Kabul into a city of gardens, as a haven from the desert and mountains. In his own garden, the Mughal emperor Babur asked for an open tomb so that his corpse would bloom with wildflowers. The Women’s Garden, the Gardens of Babur, the ruins of the Gardens of Fidelity, and, just outside the city, the Gardens of Kabul. A man named Najibullah Kabuli built the Gardens of Kabul after the fall of the Taliban. He planted each tree by hand — pine, cherry, apricot, orange, lemon, pomegranate. He said he knew when the trees were sick. Once, Kabuli watched a water tanker drive over the branch of a tree. He stopped the driver and said, “What if I cut your arm off? How would you feel? Well, that’s how the tree feels.”

The first time I met Kabuli, he had just returned from a trip to Dubai and was carrying a jar of honey from Yemen that was known to grant sexual power. He said it cost him $400, and gave everyone in the room a spoonful.

Kabuli is an ex–television host, and the party chief of Mosharekat, the Iranian reform movement. He has pockmarked cheeks and black eyes. He owns a pet wolf from Russia.

Kabuli invited me to see the gardens. When we arrived, the clouds were thick, all the way to the horizon. Snow covered the ground and swirled in a bitter wind. There were no guards on duty. Kabuli brought eight bodyguards with us, and they all waited in an armored vehicle outside the gate. Kabuli ordered one of his overweight guards to exercise. At the entrance we found a white puppy shaking in the snow. Kabuli ordered the guards to find the puppy a home. Kabuli wanted to be a man of the people. He offered gifts to people on the street and planted trees in old empty places. Kabuli means “man of Kabul,” he reminded us.

Snow swept into the trees. Roses were frozen in half-bloom. Two fat-tailed sheep that lived in the garden played on the walkway. They were Kabuli’s pets, and he’d known them since they were lambs. They slept in the old hamburger shack and had never been apart.

One of the guards, a former opium addict, followed us inside. Kabuli had found him two years earlier, alone in the snow, without shoes, and decided to adopt him. His only job was to walk ten feet behind us bearing a box of dates from Saudi Arabia. We ate the cold dates as we walked. “These are the dates of kings,” Kabuli said. A couple appeared out of a tangle of dark foliage. We weren’t expecting one another. Kabuli smiled and offered them dates. They accepted. “They are horny,” Kabuli said. “Like two sheep.”

In the garden, Kabuli has built dark and spacious rooms that lovers sometimes use, each labeled with the names of provinces: Bamyan, Kandahar, Khost. “On Fridays,” he said, “the garden hosts two thousand to three thousand couples. Most are engaged, or else they arrive in secret.” They disappear, maybe to make love in the Helmand room.

The former opium addict wandered off to eat dates. Habib waited by the roses. He was covered in snow and was fading into it. Kabuli brought me to a pomegranate tree.

Kabuli took a knife to the fruit. Juice seeped from the slit. He put his fingers inside and tore it open. The sound was like teeth on an apple. “It’s fresh,” he said. “It’s beautiful. It’s a grenade full of blood.” He made the grenade weep with his fingers. He wanted the seeds. He took his teeth to them. The juice was the only thing red in the snow.

The pomegranate is called the jewel of winter. The Koran describes a heavenly paradise of four gardens of earthly fruits, of which the pomegranate is one. Each pomegranate on earth, according to this telling, contains one seed that is descended from paradise, so that when we eat the pomegranate we are also eating paradise. Eating these seeds will purge the body of its longing to be loved.